Roman Festivals

The festival of Nemoralia (aka Festival of Torches) was celebrated by the ancient Romans either on 13–15 August or on the August Full Moon, in honor of the goddess Diana (Diana Nemorensis). This festival was later adopted by Catholics as The Feast of the Assumption.

Ovid describes the celebration thus:

“In the Arrician valley, there is a lake surrounded by shady forests, Held sacred by a religion from the olden times… On a long fence hang many pieces of woven thread, and many tablets are placed there as grateful gifts to the Goddess. Often does a woman whose prayers Diana answered, With a wreath of flowers crowning her head, Walk from Rome carrying a burning torch… There a stream flows down gurgling from its rocky bed…”

On this day, worshippers would form a shimmering procession of torches and candles around the dark waters of Lake Nemi, Diana’s Mirror. The lights of their candles join the light of the moon, dancing in reflection upon the surface of the water. Today’s festival is held in the Greek fashion.

Hundreds join together at the lake, wearing wreaths of flowers. According to Plutarch, part of the ritual (before the procession around the lake) is the washing of hair and dressing it with flowers. It is a day of rest for women and slaves. Hounds are also honored and dressed with blossoms. Travelers between the north and south banks of the lake are carried in small boats lit by lanterns. Similar lamps were used by Vestal virgins and have been found with images of the Goddess at Nemi.

One 1st century CE Roman poet, Propertius, did not attend the festival, but observed it from the periphery as indicated in these words to his beloved:

“Ah, if you would only walk here in your leisure hours. But we cannot meet today, When I see you hurrying in excitement with a burning torch To the grove of Nemi where you Bear light in honour of the Goddess Diana.”

To Do Today

Requests and offerings to Diana may include: small written messages on ribbons, tied to the altar or to trees; small baked clay or bread statuettes of body parts in need of healing; small clay images of mother and child; tiny sculptures of stags; dance and song; and fruit such as apples.

In addition, offerings of garlic are made to the Goddess of the Dark Moon, Hecate, during the festival. Hunting or killing of any beast is forbidden on Nemoralia.

Source: Wikipedia

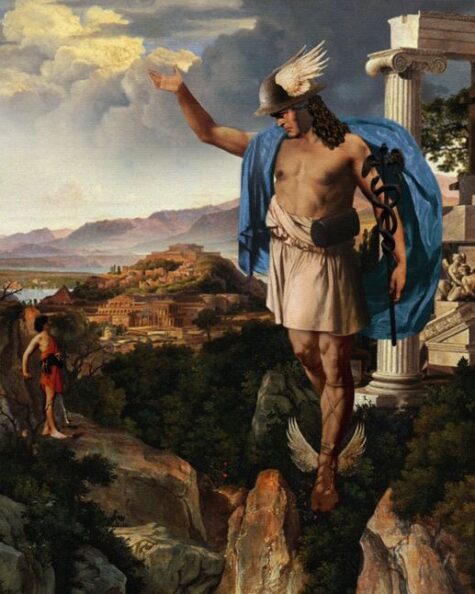

Mercuralia is a Roman celebration known also as the “Festival of Mercury”. Mercury (Greek counterpart: Hermes) was the god of merchants and commerce. On May 15 merchants would sprinkle their heads, their ships and merchandise, and their businesses with water taken from the well at Porta Capena.

Some traditions celebrate the Mercuralia on May 4 because Mercury is the Roman incarnation of the Greek god Hermes. The sacred number of Hermes is four and it is said that his mother Maia gave birth to him on the fourth day of the month. The month of May is, of course, named after Maia.

About Mercury:

Mercury is a trickster spirit who is happy to masquerade as other spirits. Long ago the Italian deity Mercury was syncretized to Greek Hermes. The two are now virtually indistinguishable, but they are not the same spirit. Mercury is urban, while the roots of Hermes lie in the rustic countryside. Hermes has a a broader base of interests, while Mercury is a spirit of money, finances, and prosperity. His name is related to words like merchants, merchandise, or commerce as well as mercenary, a soldier of fortune.

Mercury is a generous spirit but his temperament is mercurial. He loves practical jokes and word games. Always be exceptionally careful how you phrase petitions to him, paying close attention to nuance and implication, lest he give you what you accidentally asked for, rather than what he knows very well that you desire.

Mercury has quicksilver intelligence and wit. He is easily bored. Keep him entertained and he’ll be more likely to keep you happy, healthy, and prosperous. Although Mercury patronizes the dishonest, he may also be invoked to protect against them.

Homeric Hymn to Hermes:

I sing about Hermes, the Cyllenian slayer of Argus, lord of Mt. Cyllene and Arcadia rich in flocks, the messenger of the gods and bringer of luck, whom Maia, the daughter of Atlas, bore, after uniting in love with Zeus.

She in her modesty shunned the company of the blessed gods and lived in a shadowy cave; here the son of Cronus used to make love to this nymph of the beautiful hair in the dark of night, without the knowledge of immortal gods and mortal humans, when sweet sleep held white-armed Hera fast.

But when the will of Zeus had been accomplished and her tenth month was fixed in the heavens, she brought forth to the light a child, and a remarkable thing was accomplished; for the child whom she bore was devious, winning in his cleverness, a robber, a driver of cattle, a guide of dreams, a spy in the night, a watcher at the door, who soon was about to manifest renowned deeds among the immortal gods.

Maia bore him on the fourth day of the month. He was born at dawn, by midday he was playing the lyre, and in the evening he stole the cattle of far-shooting Apollo.

So hail to you, son of Zeus and Maia. Hail, Hermes, guide and giver of grace and other good things.

Invocation to Hermes-Mercury-Tjehuti:

Hail to you, Hermes-Mercury-Tjehuti,

Fleet-footed Messenger of the Gods,

In all your many faces.

Come down from Mount Olympus,

Fly in from the mighty city of Roma,

Rise up from the land of Kemet,

Race across land and sea with your legendary speed,

And come join me this day!

As Hermes you are known as Argophontes,

The Psychopomp who guides souls to the Underworld,

Who, with your wand, bestows and banishes sleep and guides us through dreams,

You whose cleverness and oratory is unmatched,

With honeyed tongue and charm you ease your way through conflict,

Divine trickster extraordinaire,

Patron of learning and the sciences,

Patron of travelers on their journeys,

Of thieves and merchants,

Of wrestlers and magicians.

Ritual For The Mercuralia

The Greeks believed that the Egyptian god Tjehuti (Thoth) was also an incarnation/aspect of Hermes (or vice versa). This ritual honors the tri-form nature of this God by the name of Hermes-Mercury-Tjehuti.

I see Mercury as the most materially-oriented of the three aspects, focusing on business, commerce, and finances. I see Tjehuti as the most spiritually-oriented of the three aspects, focusing on wisdom, knowledge, abstract concepts, and the higher self. I see Hermes as a dynamic balance of the two, the aspect that binds them together.

For a ritual honoring and invoking Mercury, Hermes, and Tjehuti. You will need the following:

- Orange candle (representing Hermes)

- Yellow candle (representing Mercury)

- Purple candle (representing Tjehuti/Thoth)

- Fresh and dried peppermint (alternatively the candles can be anointed with peppermint essential oil)

- A dime with the head of Mercury on it (optional)

Set the mood by reading the Homeric Hymn to Hermes (above). Then invoke the Messenger of the Gods by reading aloud the Invocation to Hermes-Mercury-Tjehuti (above).

- Light the orange candle and say:

“As Mercury you rule communication and commerce.”

- Light the yellow candle and say:

“As Tjehuti you are the Voice of Ra,

Keeper of the Akashic Records and Karma,

Great one of truth, wisdom, and knowledge,

Great of Magick, Great of Healing.”

- Light the purple candle and say:

“Hermes-Mercury-Tjehuti,

I welcome you with an open mind and an open heart!”

Sprinkle dusted peppermint onto the candles and/or place freshly picked peppermint by the candles. If you have the dime, place it mercury side up next to the candles.

Spend time with the God’s presence and/or tell him of any financial, communicative, motivational, career, educational, or any other problem you’re having that is related to his many powers if you wish his help. Remember, his aid is less direct than many of the other deities’, for he is the God of cunning, guile, and oratory. Finally, close by saying:

Thank you for coming, blessed Hermes! Come and go in peace!

Extinguish the orange candle

Thank you for coming, blessed Mercury! Come and go in peace!

Extinguish the yellow candle

Thank you for coming, blessed Tjehuti! Come and go in peace!

Extinguish the purple candle

If you had freshly picked peppermint, leave it outside as an offering. Leave what is left of the extinguished candles at a busy crossroads. Leave the dime as an offering in a place where there might be merchants, magicians, travelers, jokesters or thieves.

Sources:

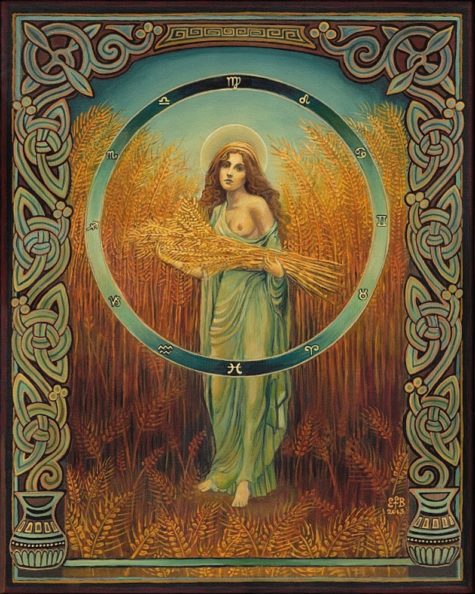

Today (April 12) is the first day of the Ludi Cereales, another spring vegetation festival, this one in honor of the goddess Ceres, goddess of grains and cereal crops. It lasts for eight days, and like the Megalesia before it, the Cerealia culminates on its final day.

During Roman times, one of the symbolic rituals of the final day was the release of foxes into the Circus with flaming brands attached to their tails despite the fact that Ceres is notoriously a peaceful goddess and most often accepts offerings of spelt cakes and salt, as well as incense.

In the countryside, people offer milk, honey, and wine on the Cerealia (particularly the final day), after bearing them thrice around the fields.

More About This Festival

Ceres is the Goddess of agriculture, and was credited with the discovery of spelt wheat, the yoking of oxen and ploughing, the sowing, protection and nourishing of the young seed, and the gift of agriculture to humankind; before this, it was said, man had subsisted on acorns, and wandered without settlement or laws. She was the first to “break open the earth”, and all activities of the agricultural cycle were protected by her laws. She held the power to fertilize, multiply and fructify plant and animal seed, whose offspring were the physical incarnations of her power.

Her first plough-furrow opened the earth (Tellus’ realm) to the world of men and created the first field and its boundary; she thus determined the course of settled, lawful, civilized life. She mediated between plebeian and patrician factions. She oversaw the transition of women from girlhood to womanhood, from unmarried to married life and motherhood and the growth of children from infancy. Despite her chthonic connections to Tellus, she was not, according to Spaeth, an underworld deity. Rather, she maintained the boundaries between the realms of the living and the dead.

Given the appropriate rites, she would help the deceased into afterlife as an underworld shade (Di Manes): otherwise, the spirit of the deceased might remain among the living as a wandering, vengeful ghost.

The goddess was worshiped in many ways. There was the porca praecidanea, which involved sacrificing a fertile female pig and was necessary before a harvest. Cato indicates that sacrifices of any large food item will do, however, and suggests a pumpkin as an acceptable substitute for a pig, since it can be cut open and the seeds offered to Ceres in much the same way the entrails of the pig would be. After the offering of the porca praecidanea, it was customary to also give the goddess a libation of wine.

The poor could offer wheat, flowers, and a libation. The expectations of afterlife for initiates in the sacra Cereris may have been somewhat different, as they were offered “a method of living” and of “dying with better hope”.

Ceres’ major festival was the Cerealia – the ludi cereales, culminating on April 19 to celebrate the growth of grain and other agricultural products. Its original form is unknown; it may have been founded during the regal era. During the Republican era, it was organised by the plebeian aediles, and included ludi circenses (circus games). These opened with a horse race in the Circus Maximus, whose starting point lay just below the Aventine Temple of Ceres, Liber and Libera. In a nighttime ritual after the race, blazing torches were tied to the tails of live foxes, who were released into the Circus. The origin and purpose of this ritual are unknown; it may have been intended to cleanse the growing crops and protect them from disease and vermin, or to add warmth and vitality to their growth

Religiously, the purpose of the races and the games were to make the goddess favorably disposed toward the Roman people, so that she would give them a good harvest.

Visual depictions of Ceres were largely derived from Greek portrayals of Demeter. On two coin types, a bust of Ceres was pictured on one side, while a yoke of oxen was on the other. On other coins, she wears a crown of grain stalks called a corona spicea, holds stalks of wheat, and is occasionally pictured with wheat and barley grains. One coin actually portrayed her wearing a modius, an instrument used to measure grain, on her head. Another pictures a bust of series on one side, and a pair of seated male figures with a wheat stalk to their side on the other. The seated men represent the official distribution of grain to the people. Annona, the goddess who personified the wheat supply, appears alongside Ceres on several coins from the imperial period. Reliefs from the Augustan period have even gone so far as to depict her as a plant growing out of the ground. In one her bust emerges from the earth, holding bunches of poppies and grain in her upraised hands while two snakes twine about her arms.

Ceres also assimilated the visual symbols of the Eleusinian Mysteries, which most Romans observed in her name. Ceres is depicted with symbols of the Mysteries, such as riding in a chariot drawn by snakes while holding a torch in her right hand.

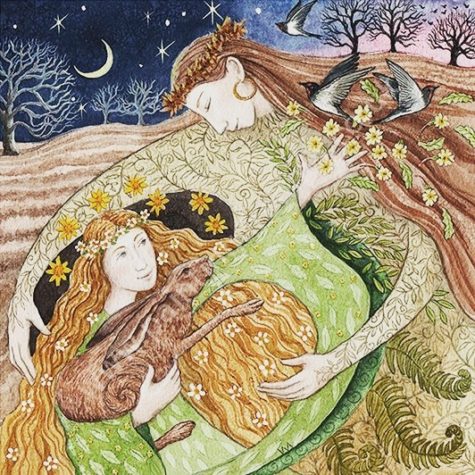

Persephone’s Return ~ A Ritual For The Cerelea

Most often celebrated on the last day of the Ludi Cereales (or April 19).

- Color: Green

- Element: Earth

- Offering: Flowers. Begin something new.

- Daily Meal: Dark, coarse bread. Root vegetables. Poppy seeds. Millet. Nuts and seeds.

Altar: Upon a green cloth set as many spring flowers as possible, a bowl of earth saved from the day of Persephone’s descent, and the figure of a girl’s head emerging from the earth.

Invocation to Persephone’s Return

Let the Earth take joy!

Demeter’s heart is warmed,

For her beloved daughter,

The maiden of Spring,

Has returned to the upper world!

Let all upon the Earth take joy!

Flowers spring from her footsteps,

Grass spreads between her toes,

The promise of the summer wind

Falls like butterflies newly loosed

From her hair the color of poppies and clay.

Let us all take joy!

She who descended in the autumn,

She who is married to Death

And yet arises in the bringing of Life,

She who has passed the bodies

Of a thousand corpses,

She who has sung with the shades

Of a thousand ancestors,

She rises to greet the morning sun

For as long as it is her time.

Then, like all things, she will descend again,

Into the depths of the Earth,

And we, we shall learn to love that cycle

Of rising and falling, of birth and death,

And truly call it a blessing.

Chant:

Kore Kore Kore Proserpina

Let one chosen for the work of the daily ritual carry the bowl of earth from person to person about the hall, and let each one take a bit of the earth and rub it on their faces, and let it remain until the evening ablutions.

~Info collected from various sources, including the Pagan Book of Hours

This festival marks the start of Spring in the old Roman calendar. Each year the Feriae Marti was held, beginning on the Kalends of March and continuing until the 24th. Dancing priests, called the Salii, performed elaborate rituals over and over again, and a sacred fast took place for the last nine days. The dance of the Salii was complex, and involved a lot of jumping, spinning and chanting. On March 25, the celebration of Mars ended and the fast was broken at the celebration of the Hilaria, in which all the priests partook in an elaborate feast.

March is the third month of the year in the Gregorian calendar system, but was actually the first month on the Roman calendar. Originally named Martius, this month in Ancient Rome was characterized by religious festivals and preparations for war. Mars, the Roman god of war was responsible for protecting Rome and securing victory in military campaigns. He is not to be confused with Ares, the impulsive Greek god of war; Mars was depicted as a more “level-headed” and “virtuous” deity than his Grecian counterpart.

General frivolity was characterized by large processions, animal sacrifices, athletic competitions, and musical performances. Courts were closed, and some agricultural chores were suspended to honor the deities. Merry-making with seeds wasn’t restricted though. Some accounts say Romans tossed seeds in the air during the festival to honor the pending thrust of spring.

During the months of March and October, specially-trained religious leaders, called flamen Martialis, led several Mars-centered festivals including:

- Feriae Marti (celebrating the new year)

- Equirria (the blessing of war horses)

- Tubilistrum (to cleanse and favor trumpets)

One of the most important rituals performed during this time was the rousing of Mars before battle. This critical ritual was performed by the commander of the Roman army who “shook the sacred spears,” shouting, “Mars, vigilia!.”

Because early Roman writers associated Mars with not only warrior prowess, but virility and power, he is often tied to the planting season and agricultural bounty.

Ritual For The Feriae Marti – Festival of Mars

- Color: Red

- Element: Fire

Altar: Set out a red cloth and lay crossed weapons, such as spears and swords, upon it. Lay a helm in the center, a horn, and a burning red candle or torch.

Offerings: Candles. Finger-shaped cakes (strues). Acts of courage, especially those which force one to fight for the defense of another or of one’s beliefs. In the morning, the exercise of Gymnastika shall be hard aerobic movements.

Daily Meal: Finger-cakes. Spicy foods, such as cayenne and chilies. Meat from uncastrated male animals.

Invocation to Mars:

Mars, warrior god, Fire that leaps

And dances, Protector of cities

And of this house, and our spirits,

Courageous one, mirror us back

Some of your courage.

Fearless one, show us a path

Through our many fears.

Armored one, give us protection

From all who would harm us.

And may your sword turn away

All danger from our flesh,

Our bones, our house, our home,

Our hearth and our hearts

Our eyes and our spirits.

Protect us from destruction and ruin,

O fiery god of the shining spear.

We hail you, eternal warrior,

And ask that you grant us

Some small measure

Of your boundless fiery heart.

Chant: (To be accompanied by drums and people clashing blades against shields in the manner of the Salii of ancient times)

Gloria Martial! Gloria Martial! Gloria Martial!

Honoria et Gloria Honoria et Gloria!

A libation of red wine is poured out for Mars. One person lifts the horn and winds it, long and slow, five times, and the rite is ended.

Sources:

The festival of the Robigalia is celebrated to appease the God Robigus (or perhaps the Goddess Robigo; the gender of this deity, who originated as one of the numinae, is uncertain), who is the deity of wheat-rust, mildew, and blight.

It is an ancient festival of the agricultural calendar, and is celebrated by the Flamen Quirinalis. Both a red dog and sheep are sacrificed to Robigus, along with wine and incense; prayers are then spoken to protect the crops. There is some connection with the ascension of the star Sirius, but it is unclear.

Games (ludi) in the form of “major and minor” races were held. The Robigalia was one of several agricultural festivals in April to celebrate and vitalize the growing season, but the darker sacrificial elements of these occasions are also fraught with anxiety about crop failure and the dependence on divine favor to avert it.

Verminus, a God who protects cattle against worm disease, might also be honored on this day.

The Robigalia has been connected to the Christian feast of Rogation, which was concerned with purifying and blessing the parish and fields and which took the place of the Robigalia on April 25 of the Christian calendar.

Sources:

Nowadays, whenever we hear the term Bacchanalia getting thrown about it is typically used to describe wild partying that has gotten way out of control. In the popular imagination, the Bacchanalia are often characterized by frantic participants moshing together in a pit of sexual orgies.

The Bacchanalia were free-spirited and sexually charged festivals that involved pagan mysticism, wild sex and divine communion which allowed its celebrants’ to achieve states of euphoria that hovered between divine ecstasy and the oblivion of nothingness. Those who have spent a week at one of the Hedonism resorts in Jamaica would probably find the sexually charged atmosphere of the Bacchanalia remarkably familiar.

The cult of Bacchus was a mystery religion that originated in Asia Minor (modern day Turkey) and spread throughout Greece and into southern Italy where it became extremely popular among the Romans. Despite their notoriety, not much is known about the Bacchanalia. This is largely due to the fact that mystery religions were closed to the uninitiated and their inner-workings kept secret from the outside world. However, scholars have managed to piece together fragments from ancient legal documents, historical texts and plays that can help give us a glimpse into the bacchanalian festivities.

The Bacchanalia first appeared in Greece around 700 BC and eventually found their way into Italy around the fourth century BC. The first bacchanals were held twice yearly in the middle of winter and were reserved for girls and women who performed their rites naked. By the time Rome had become the preeminent power in the Mediterranean after their victory over Carthage in the Second Punic War (202 BC), the rituals had opened up considerably making them quite popular with the natives.

Admission was extended to men and people of all social classes; even slaves could even join in on the fun. With the increased popularity, celebrations were taking place as often as five times a month.

The time and location of the bacchanals were usually closely guarded secrets. Priests and priestesses preferred to hold their gatherings in secluded forests where their privacy could be ensured. On the day of the festival, devotees would prepare some goats by painting their horns gold. Special torches dipped in sulphur and charcoal was also made. Devotees often wore fawn skins that emulated forest animals. Skimpy outfits or even complete nudity was also par for the course. Participants would often carry along their favorite sex toy; women would bring sexy wands while men might bring along a wooden phallus.

After nightfall celebrants would proceed to a forest clearing by dancing to the sounds of crashing cymbals and loud music. Once the celebrants arrived at the appointed place, they could be seen quaffing down wine, dancing, leaping, whirling, screaming and generally working themselves up into a frenzied state. They would inspire each other into ever greater acts of ecstasy, whereby the whole scene would descend into a writhing mosh pit of sexual orgies.

The aim was to achieve a heightened state of ecstasy in which the devotee’s souls would be temporarily freed from their physical existence. It was in these moments that the worshipers hoped to commune with Bacchus and obtain a glimpse of what they would someday meet in the afterlife after their resurrection.

The festival would reach its climax with frantic feats of strength and ecstasy, such as ripping trees out of the ground and eating the raw flesh of their sacrificial animals. The latter act was a sacrament similar to communion where the devotees assumed the identity of Bacchus. By symbolically drinking his blood and eating his body, the devotees believed they became one with Bacchus.

The euphoric devotees would then rush over to the banks of a nearby river with their flaming torches and dip them into the water. Since their torches were made with sulfur and charcoal, they would emerge from the water still burning, a symbol of Bacchus’s power.

Source: The Bacchanalian

Termini in Roman mythology began as boundary markers between wilderness settings. The termini were rural boundary stones marking property lines between fields and neighbors. There was an annual ceremony each 23rd day of February called the Terminalia when first fruits were offered and libations of oil and honey were poured over the termini to renew the power or forces within the boundary stones between properties. Ovid presents the story as follows

When night has passed, let the god be celebrated

With customary honour, who separates the fields with his sign.

Terminus, whether a stone or a stump buried in the earth,

You have been a god since ancient times.

You are crowned from either side by two landowners,

Who bring two garlands and two cakes in offering.

An altar’s made: here the farmer’s wife herself

Brings coals from the warm hearth on a broken pot.

The old man cuts wood and piles the logs with skill,

And works at setting branches in the solid earth.

Then he nurses the first flames with dry bark,

While a boy stands by and holds the wide basket.

When he’s thrown grain three times into the fire

The little daughter offers the sliced honeycombs.

Others carry wine: part of each is offered to the flames:

The crowd, dressed in white, watch silently.

Terminus, at the boundary, is sprinkled with lamb’s blood,

And doesn’t grumble when a sucking pig is granted him.

Neighbours gather sincerely, and hold a feast,

And sing your praises, sacred Terminus:

‘You set bounds to peoples, cities, great kingdoms:

Without you every field would be disputed…

These rural termini and feast of landmarks had their state counterpart in Terminus. The story told by Ovid about the sacred boundary stone which stood, in the temple of the Capitoline Jupiter, continues:

What happened when the new Capitol was built?

The whole throng of gods yielded to Jupiter and made room:

But as the ancients tell, Terminus remained in the shrine

Where he was found, and shares the temple with great Jupiter.

Even now there’s a small hole in the temple roof,

So he can see nothing above him but stars.

Since then, Terminus, you’ve not been free to wander:

Stay there, in the place where you’ve been put,

And yield not an inch to your neighbour’s prayers …

~Ovid, Fasti Vol II

A Simple Terminalia Celebration

- Themes: Earth; Home

- Symbols: Owl; Geranium

- Presiding Goddess: Minerva

About Minerva:

About Minerva:

This Etruscan/Italic goddess blended the odd attributes of being a patroness of household tasks, including arts and crafts, and also being the patroness of protection and war. Today she joins in pre-spring festivities by helping people prepare their lands for sowing and embracing the figurative lands of our hearts, homes, and spirits with her positive energy.

To Do Today:

In ancient times, this was a day to bless one’s lands and borders. Gifts of corn, honey, and wine were given to the earth and its spirits to keep the property safe and fertile throughout the year. In modern times, this equates to a Minerva-centered house blessing.

Begin by putting on some spiritually uplifting music. Burn geranium-scented incense if possible; otherwise, any pantry spice will do. Take this into every room of your home, always moving clockwise to promote positive growing energy. As you get to each room, repeat this incantation:

Minerva, protect this sacred space

and all who live within.

by your power and my will,

the magic now begins!

Wear a geranium today to commemorate Minerva and welcome her energy into your life.

Sources:

The Feralia was the closing festival of the ancient Roman festival of Parentalia. During the Feralia, families would picnic at the tombs of their deceased family members and give libations to the dearly departed. It was believed that the shades of the dead could walk upon the earth above their graves during Feralia.

Roman citizens were instructed to bring offerings to the tombs of their dead ancestors which consisted of at least “an arrangement of wreaths, a sprinkling of grain and a bit of salt, bread soaked in wine and violets scattered about.” Additional offerings were permitted, however the dead were appeased with just the aforementioned.

Ovid tells of a time when Romans, in the midst of war, neglected Feralia, which prompted the spirits of the departed to rise from their graves in anger, howling and roaming the streets. After this event, tribute to the tombs were then made and the ghastly hauntings ceased.

“And the grave must be honoured. Appease your fathers’ Spirits, and bring little gifts to the tombs you built. Their shades ask little, piety they prefer to costly offerings: no greedy deities haunt the Stygian depths. A tile wreathed round with garlands offered is enough, A scattering of meal, and a few grains of salt, and bread soaked in wine, and loose violets: Set them on a brick left in the middle of the path…

…and hide the gods, closing those revealing temple doors, Let the altars be free of incense, the hearths without fire. Now ghostly spirits and the entombed dead wander, Now the shadow feeds on the nourishment that’s offered. But it only lasts till there are no more days in the month Than the feet that my metres possess. This day they call the Feralia because they bear [ferunt] Offerings to the dead: the last day to propitiate the shades.” – Ovid

To indicate public mourning, marriages of any kind were prohibited on the Feralia, and Ovid urged mothers, brides, and widows to refrain from lighting their wedding torches. Magistrates stopped wearing their insignia and any worship of the gods was prohibited as it “should be hidden behind closed temple doors; no incense on the altar, no fire on the hearth.”

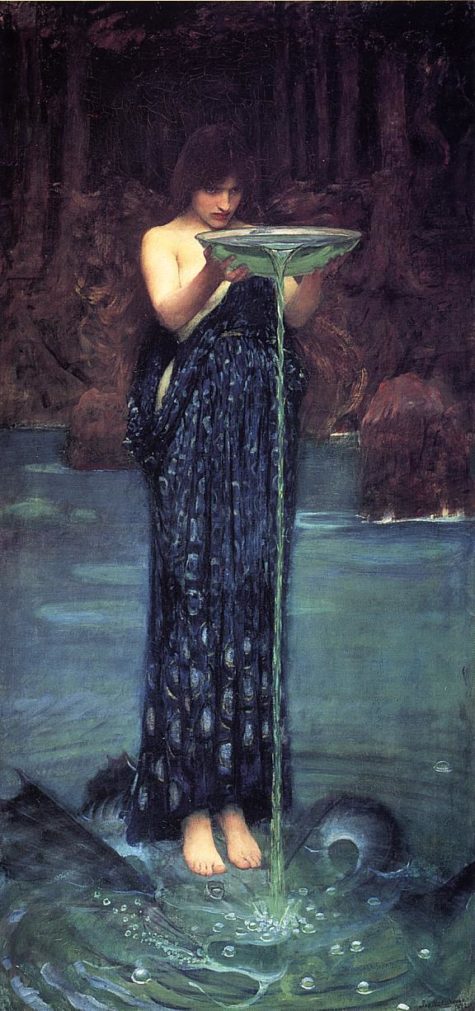

Februalia, Februa, and also Februatio, was the Roman festival of ritual purification, later incorporated into Lupercalia. The festival, which is basically one of Spring washing or cleaning (associated also with the raininess of this time of year) is old, and possibly of Sabine origin. According to Ovid, Februare as a Latin word which refers to means of purification (particularly with washing or water) derives from an earlier Etruscan word referring to purging.

The Roman month Februarius (“of Februa,” whence the English February) is named for the Februa/Februatio festival, which occurred on the 15th day of the Roman month. A later Roman god Februus personified both the month and also purification, and is named for them. Thus, the month is named for the festival and not for the god.

Here is a ritual for Februata, and is appropriate any day during the month of February:

- Color: White

- Element: Earth

- Altar: Spread with a clean white cloth and place thereupon four white candles and a bowl of water, very simply.

- Offerings: Clean something externally, and at the same time clean something internally.

- Daily Meal: Fasting for the day. Drink plenty of water.

Februata Invocation

The winter has lain heavily upon us,

Juno Februata, Queen of the new light,

And we are sunk in layers of thought

Like a hibernating mole

Beneath layers of earth.

Bring us forth into the light, Lady!

Let us remove all filth

From our bodies and our souls,

Making them a place of clarity.

Chant:

Februus Februus Lucina Lucina

(There is no further ritual; all silently take cleaning tools and being to thoroughly clean the entire building, ending with a ritual bath. As each cleans, they should meditate on what part of the mind or spirit needs cleansing, and let the physical cleansing aid in the spiritual aspect.)

Sources: Wikipedia and Pagan Book of Hours

The Goddess Carmenta is celebrated on two dates of the Roman calendar, (January 11 and 15), each day called Carmentalia. These dates should be considered as two separate festivals, rather than one festival extending over this period, yet it is not clear to us today, any more than it was during the Late Republic, why two such holidays should be in such close proximity in one month.

The festival, chiefly observed by women, celebrates Carmenta, who is the Goddess of women’s health, birthing, and prophecy. She is the inventor of letters, as Minerva is the inventor of numbers. She tells the future through Her sister Porrima and reveals the past through Her sister Postvorta, while Carmenta knows all that happens in the present.

Together the three Carmenae sisters are the Good Fates, the Three Mothers, and the Muses. The very name of Carmenta was given to song (carmen) and Latin terms for poetry, charms, and speaking-in-tongues. With Her songs she would soothe the ill and taught women how to care for themselves and their children. Her sanctuaries thus became places for women and children to receive traditional medical treatments using herbs and music.

Carmenta takes us back to a very early period, a time well before the beginnings of Rome around three thousand years ago, back into the Italian Bronze Age. She takes us back to the ecstatic tradition of the female priestesses called vates in which Latin religion began and in which the Religio Romana was first founded.

The sacred grove of Carmenta, the most ancient sanctuary in all of Rome, was located at the foot of the Capitoline Hill. It is still visited today where people gather waters from Her sacred spring. It was in this very grove that Carmenta appeared to Numa Pompilius in his dreams as the nymph Egeria. She instructed Numa on how to commune with the Gods.

With Egeria’s instruction, Numa Pompilius then established rituals for the Gods, festivals, and a calendar by which the Romans could attend these. Numa set out sanctuaries for Gods and Goddesses and he created colleges of priests and priestesses to serve the Gods and Goddesses. Egeria taught Numa the laws which he handed down to the Romans and which still govern our sacramental rituals today.

One of the laws of Numa states:

“The Gods are not to be represented in the form of man or beast, nor are there to be any painted or graven image of a deity admitted (to your rites).”

As one of the oldest Goddesses of Rome, whose worship was established by Numa, Carmenta was never represented by an image. It was sufficient to feel Her presence in the sacred grove below the Capitoline. In the same way, Vesta, Goddess of the Hearth, is never represented by an image but only by living fire.

Another law of Numa holds that:

“Sacrifices are not to be celebrated with an effusion of blood, but consist of flour, wine, and the least costly of offerings.”

The restriction against the use of blood sacrifices was so strong in the worship of Carmenta that no one was allowed to enter Her sacred grove wearing anything made of leather or animal hide. It is not right to take the life of another creature in worshiping the Goddess who helps birth life into the world. And thus it follows that today we offer Carmenta bay leaves as incense, a libation of milk, and popana cakes made of soft cheese and flower.

Invocation to Carmenta

Goddess of Women’s Health

Come, be present, Carmenta.

May Your sisters Porrima and Postvorta attend You.

With joyful mind come, Mother Carmenta, on You I call,

Come, stand by me, stay, and listen to my pleas.

Speak to me once more, in Your own words, as You did before.

In Your sacred grove where Egeria counseled King Numa,

bear forth now Your soothing songs to dispel our sorrows.

Come forth! I call to You, Good Goddess,

Great Goddess of charms.

Give voice, happy Voice of song,

With soothing songs as will cure our ills, or whatever else we fear.

Spare our daughters heavy with child, spare our wives in their pangs of labor,

Care for the mothers who worry over their children.

With pious rite I call out, I summon,

I entice with songs that You come forth, Carmenta,

And look favorably upon the matrons of our families.

In You, dearest Mother, in Your hands we place our safekeeping.

In offering to You this cake of cheese I pray good prayers

in order that, pleased with this offering of popana,

May You be favorable towards our children and to us,

Towards our homes and our households.

More About The Festivals:

According to legend, the cult of Carmenta predated Rome itself. In some accounts She was known as Nicostrate, the mother of Evander, who was fathered by Mercurius. Evander was the legendary founder of Paletum, a village that gave its name to the Palatine Hill. Her sacred grove, therefore, may have originally lain beneath the Palatine Hill as some ascribe it.

Indeed, it may be that it was in Her sacred grove beneath the Palatine that Romulus and Remus were said to have been discovered being suckled by a she-wolf, since Carmentis was so closely associated with the care of infants.

It was said that later Numa Pompilius founded a sacred grove for Her beneath the Capitoline Hill. The dedication of two groves to Carmentis is one possible reason why there were two days celebrated as Carmentalia in the month of January.

It was proposed by Huschke that the two festival days represented the Latins of Romulus and the Sabines of Titus Tatius, just as there were two companies of Luperci and two companies of Salii. Were that the case we might expect that She once had a sacred grove on the Esquiline Hill, and that Numa’s dedication beneath the Capitoline represented a union of the two culti Carmentalis.

The fasti Praeneste suggests that the second date was added by a victorious Roman general who had left the City by the Porta Carmentalis for his campaign against Fidenae. The gate received its name from its proximity to the sacred grove of Carmentis.

Yet another story was told by Ovid, linking the two dates to a protest by the matrons of Rome in 195 BCE. During the fourth century the Roman Senate had granted patrician matrons the privilege of riding in two- wheeled carriages in reward for their contribution in gold to fulfilling a vow to Apollo made by Camillus. The privilege was later to be temporarily revoked during the Second Punic War (215 BCE) along with sumptuary laws that limited the use of colored cloth and gold that women could wear, in order to save on private expenses and war materials (horses) and thus help in the war effort.

But the Senate did not at first renew the privileges at war’s end. In 195 Tribunes Marcus Fundanius and Lucius Valerius finally called for the repeal of this lex Oppia, but they were opposed by the brothers Marcus and Publius Junius Brutus.

Supporters for repealing the lex Oppia, and those who supported its remaining in effect, gathered daily on the Capitoline to argue over the matter. Soon women began to join in the disputes, their numbers increasing daily, even so much as women from the countryside entered into the City to advocate for their rights. The natural place for them to first congregate would have been at the grove of Carmentis. This may be what Ovid indicates by linking the protest to the Carmentalia.

Consul Marcius Porcius Cato spoke out against repealing the lex Oppia. The women then resolved to “refuse to renew their ungrateful husbands’ stock” until their privileges were restored, Ovid referring to the women resorting to abortion as their means of protest.

In a later period the Temple of the Bona Dea would become associated with the use of abortive herbs, and Carmentis associated with the use of the same herbs in birthing. In actuality both Carmentis and the Bona Dea were associated with birthing or prevention of pregnancy, and the difference between the Capitoline and Aventine temples may have been one of class distinction. Eventually the matrons of Rome regained their rights and, according to Ovid, the second Carmentalia was then begun in thanks to the Goddess for Her support. Ovid’s story is the least likely and most fanciful to account for the two Carmentaliae of January.

The notion that there may have earlier been two groves dedicated to Carmentis prior to the known grove beneath the Capitoline is a reasonable speculation, but still would not account for the two festivals. We are left then with the information provided by the Fasti Praeneste, although the inscription is mutilated and uncertain. This source may indicate that while the Carmentalia held on 11 January was dedicated to Carmentis, that of 15 January was intended to honor Janus as guardian of the Porta Carmentalis.

Different aspects of Carmentis related to Janus, and thus it is possible that a festival for Him would include Carmentis in similar fashion as festivals for Ops and Consus. The fact remains that we don’t know today why the month of January has two separate festivals for Carmentis.

Ritual for the Festival of Carmenta

- Color: Red

- Element: Earth

- Offerings: Give gifts to pregnant women in need.

- Daily Meal: Eggs.

- Altar: Upon a red cloth place seven red candles and the figure of a pregnant woman. If possible, a woman who is with child should be present and honored on this day.

Carmentalia Invocation

All things grow in the dark place

Safe within the womb of the Mother,

Safe within the dream of the Mother.

The Earth lies now asleep

Full with big belly,

Each seed pregnant with hopes

Waiting for the return of the Sun.

So we are each of us,

Pregnant with hopes and dreams,

Big-bellied in our minds,

Waiting to for the moment

To begin our sacred labor.

This is the time of waiting,

Feeling the child within come to fruition,

Feeling it grow and change,

Feeling the faint motions

That signify the oncoming flood of life.

Call: May Life burst forth in a flood of joy!

Response: May Life come forth through the gate of eternity!

Call: We hail the Mother beneath our feet!

Response: We hail the Mother within our souls!

Call: We hail the Mothers from whence we descended!

Response: We hail the Mothers that are yet to bring forth!

Call: We hail the growth of possibility!

Response: We hail all that it yet to come!

Call: We hail the growth of the future!

Response: We wait for the birthing-time with open arms!

Chant:

Mother I feel you under my feet

Mother I hear your heart beat

Sources: