China

According to historical documents, on the day when Shun, who was one of ancient China’s mythological emperors, came to the throne more than 4000 years ago, he led his ministers to worship heaven and earth. From then on, that day was regarded as the first day of the first lunar month in the Chinese calendar. This is the basic origin of Chinese New Year.

The new year is by far the most important festival of the Chinese lunar calendar. A long time ago, the emperor determined the start of the New Year. Today, celebrations are based on Emperor Han Wu Di’s almanac. It uses the first day of the first month of the Lunar Year as the start of Chinese New Year. The Chinese New Year always occurs in January or February on the second new moon after the winter solstice, though on occasion it has been the third new moon.

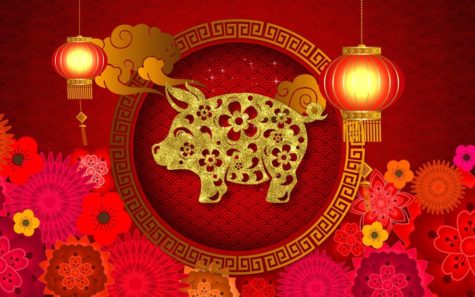

In 2019, the Chinese New Year officially begins on February 5th and ends on February 19th. This begins the Year of the Pig.

The holiday is a time of renewal, with debts cleared, new clothes bought, shops and homes decorated, and families gathered for a reunion dinner. Enjoying extravagant foods with family and friends is arguably the cornerstone of the occasion, along with receiving the ubiquitous red envelopes full of cash (called lai see in Cantonese, or hongbao in Mandarin).

Chinese New Year is marked by fireworks, traditional lion dances, gift giving, and special foods. This is one of the most important holidays. It is observed all over the world. Similar celebrations occur in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam known as the Lunar New Year or the Spring Festival. The “Spring Festival” in modern Mainland China, is China’s most important traditional festival, this public holiday starts on the Chinese New Year, and lasts for 7 days.

About The Chinese Calendar

The Chinese Calendar is a based on the cycles of the moon. The start of the New Year begins anywhere from late January to mid-February. A complete lunar cycle takes 60 years. It is composed of five cycles that are 12 years each. Each 12-year segment is named after an animal.

According to legend, Buddha called all the animals to him before he departed from earth. Only twelve came and as a reward to them, he named the years after them in the order they arrive (the order is listed below). It is believed the animal ruling of the year you are born effects your personality and “it is the animal that hides in your heart”.

The Chinese calendar uses the stem-branch system. The branches are the 12 years. There are ten stems that are used in the counting system. The stems are metal, water, wood, fire and soil; each having a yin and a yang side. There are a lot more intricacies in the system, but you should also know that the elements correlate to colors. Metal=white or golden, water=black, wood=green, fire=red, and soil=brown.

When you put all of this together you end up with the following:

- 2007 is the Year of the Red Pig

- 2008 is the Year of the Brown Rat

- 2009 is the Year of the Brown Ox

- 2010 is the Year of the White or Golden Tiger

- 2011 is the Year of the White or Golden Rabbit

- 2012 is the Year of the Black Dragon

- 2013 is the Year of the Black Snake

- 2014 is the Year of the Green Horse

- 2015 is the Year of the Green Sheep

- 2016 is the Year of the Red Monkey

- 2017 is the Year of the Red Rooster

- 2018 is the Year of the Brown Dog

- 2019 is the Year of the Brown Pig

- 2020 is the Year of the White Rat

Which Chinese zodiac animal are you?

According to the Asian astrology, your year of birth – and the animal this represents – determines a lot about your personality traits. Find the year you were born, and you can figure out which animal in the Chinese Zodiac is yours. The animal changes at the beginning of the Chinese New Year, and traditionally these animals were used to date the years.

Remember, Chinese New Year is a movable celebration, dictated by the lunar cycle, which can fall anytime between January 21 and February 20. So, if you were born during that time, you may need to do some research to figure out which animal applies to you.

- Rat: 2008, 1996, 1984, 1972, 1960, 1948

- Ox: 2009, 1997, 1985, 1973, 1961, 1949

- Tiger: 2010, 1998, 1986, 1974, 1962, 1950

- Rabbit: 2011, 1999, 1987, 1975, 1963, 1951

- Dragon: 2012, 2000, 1988, 1976, 1964, 1952

- Snake: 2013, 2001, 1989, 1977, 1965, 1953

- Horse: 2014, 2002, 1990, 1978, 1966, 1954

- Goat: 2015, 2003, 1991, 1979, 1967, 1955

- Monkey: 2016, 2004, 1992, 1980, 1968, 1956

- Rooster: 2017, 2005, 1993, 1981, 1969, 1957

- Dog: 2018, 2006, 1994, 1982, 1970, 1958

- Pig: 2019, 2007, 1995, 1983, 1971, 1959

Traditions

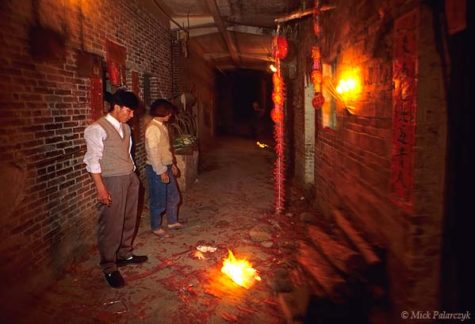

Traditions observed during the New Year stem from legends and practices from ancient times. Legend tells of a village, thousands of years ago, that was ravaged by Nian, an evil monster, one winter’s night. The following year the monster returned and again ravaged the village. Before it could happen a third time, the villagers devised a plan to scare the monster away.

The color red protects against evil. Red banners were hung everywhere. Firecrackers were set off, and people banged on drums and gongs creating loud noises to scare the beast away. The plan worked. The celebration lasted several days during which people visited with each other, exchanged gifts, danced, and ate tasty food. Today, celebrations last two weeks.

The red posters with poetic verses on it were initially a type of amulet, but now it simply means good fortune and joy. Various Chinese New Year symbols express different meanings. For example, an image of a fish symbolizes “having more than one needs every year”. A firecracker symbolizes “good luck in the coming year”. The festival lanterns symbolize “pursuing the bright and the beautiful.”

Preparing for the New Year

Spring cleaning is started about a month prior to the new year and must be completed before the celebrations begin. All the negativity and bad luck from the previous year must be swept out of the house.

Many people clean their homes to welcome the Spring Festival. They put up the red posters with poetic verses on it to their doors, Chinese New Year pictures on their walls, and decorate their homes with red lanterns. It is also a time to reunite with relatives so many people visit their families at this time of the year.

People also get haircuts and purchase new clothing. It symbolizes a fresh start. Flowers and decorations are purchased. Decorations include a New year picture (Chinese colored woodblock print), Chinese knots, and paper-cuttings, and couplets.

Flowers have special meanings and the flower market stocks up on:

- Plum blossom for luck

- Kumquats for prosperity

- Narcissus for prosperity

- Sunflowers to have a good year

- Eggplant to heal sickness

- Chom mon planta for tranquility

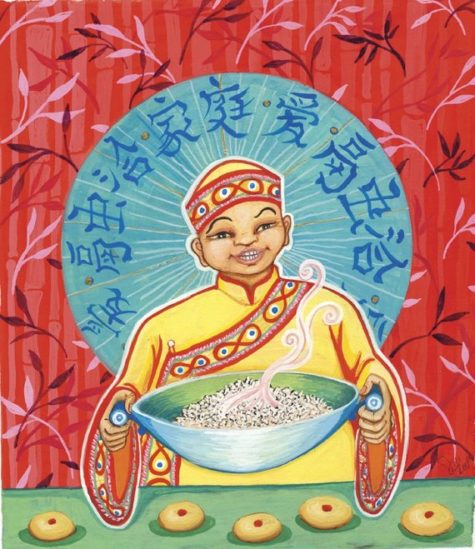

Offerings are made to the Kitchen God about a week before the New Year.

On The Eve of The Spring Festival

The Annual Reunion Dinner, Nian Ye Fan, is held on the eve of the festival. This is an important part of the celebration. Families come together and eat together. The food is symbolic. Many dishes have ingredients that sound the same as good tidings. In northern China, dumplings are served at midnight, they symbolize wealth.

In the evening of the Spring Festival Eve, many people set off fireworks and firecrackers, hoping to cast away any bad luck and bring forth good luck. Children often receive “luck” money. Many people wear new clothes and send Chinese New Year greetings to each other. Various activities such as beating drums and striking gongs, as well as dragon and lion dances, are all part of the Spring Festival festivities.

The dragon dance is a highlight in the celebrations. A team of dances mimic the movements of the dragon river spirit. Dragons bring good luck.

Lions are considered good omens. The lion dance repels demons. Each lion has two dancers, one to maneuver the head, the other to guide the back. Business owners offer the lions a head of lettuce and oranges or tangerines. The offerings hope to insure a successful year in business. Lettuce translates into “growing wealth” and tangerines and oranges sound like “gold” and “wealth” in Chinese. The lions eat the oranges, then spew them up and out into the hordes of people who eagerly tried to catch the them. After eating the lettuce, they spit out it out in a thousand pieces.

During the New Year

Red packets called Lai See Hong Bao (or Hongbao) with money tucked inside are given out as a symbol of good luck. The amount is an even number as odd numbers are regarded as unlucky.

- Bright red lanterns are hung.

- Brooms and cleaning material are put away. No cleaning takes place during the holiday so no good luck is swept out of the home.

- During the New Year celebrations people do not fight and avoid being mean to each other, as this would bring a bad, unlucky year.

- Bright colors and red are worn.

- Everyone celebrates their birthday this day and they turn one year older.

- Traditional red oval shaped lanterns are hung.

The end of the New Year is celebrated with the Lantern Festival.

Top Ten Taboos for The Chinese New Year

The Spring Festival is a time of celebration. It’s to welcome the new year with a smile and let the fortune and happiness continue on. At the same time, the Spring Festival involves somber ceremonies to wish for a good harvest. Strict rules and restrictions go without saying.

To help you with that, here are the top 10 taboos during the Chinese New Year. Follow these and fortune will smile on you.

- 1. Do not say negative words

All words with negative connotations are forbidden! These include: death, sick, empty, pain, ghost, poor, break, kill and more. The reason behind this should be obvious. You wouldn’t want to jinx yourself or bring those misfortunes onto you and your loved ones.

- 2. Do not break ceramics or glass

Breaking things will break your connection to prosperity and fortune. If a plate or bowl is dropped, immediately wrap it with red paper while murmuring auspicious phrases. Some would say 岁岁平安 (suì suì píng ān). This asks for peace and security every year. 岁 (suì) is also a homophone of 碎, which means “broken” or “shattered.” After the New Year, throw the wrapped up shards into a lake or river.

- 3. Do not clean or sweep

Before the Spring Festival, there is a day of cleaning. That is to sweep away the bad luck. But during the actual celebration, it becomes a taboo. Cleaning or throwing out garbage may sweep away good luck instead.

If you must, make sure to start at the outer edge of a room and sweep inwards. Bag up any garbage and throw it away after the 5th day. Similarly, you shouldn’t take a shower on Chinese New Year’s Day.

- 4. Do not use scissors, knives or other sharp objects

There are 2 reasons behind this rule. Scissors and needles shouldn’t be used. In olden times, this was to give women a well-deserved break.

Sharp objects in general will cut your stream of wealth and success. This is why 99% of hair salons are closed during the holidays. Hair cutting is taboo and forbidden until Lunar February 2, when all festivities are over.

- 5. Do not visit the wife’s family

Traditionally, multiple generations live together. The bride moves into the groom’s home after marriage. And, of course, she will celebrate Chinese New Year with her in-laws.

Returning to her parents on New Year’s Day means that there are marriage problems and may also bring bad luck to the entire family. The couple should visit the wife’s family on the 2nd day. They’d bring their children, as well as a modest gift (because it’s the thought that counts).

- 6. Do not demand debt repayment

This custom is a show of understanding. It allows everyone a chance to celebrate without worry. If you knock on someone’s door, demanding repayment, you’ll bring bad luck to both parties. However, it’s fair game after the 5th day. Borrowing money is also taboo. You could end up having to borrow the entire year.

- 7. Avoid fighting and crying

Unless there is a special circumstance, try not to cry. But if a child cries, do not reprimand them. All issues should be solved peacefully. In the past, neighbors would come over to play peacemaker for any arguments that occurred. This is all to ensure a smooth path in the new year.

- 8. Avoid taking medicine

Try not to take medicine during the Spring Festival to avoid being sick the entire year. Of course, if you are chronically ill or contract a sudden serious disease, immediate health should still come first. Related taboos include the following ~ Don’t visit the doctor, Don’t perform/undergo surgery, Don’t get shots

- 9. Do not give New Year blessings to someone still in bed

You are supposed to give New Year blessings (拜年—bài nián). But let the recipient get up from bed first. Otherwise, they’ll be bed-ridden for the entire year. You also shouldn’t tell someone to wake up. You don’t want them to be rushed around and bossed around for the year. Take advantage of this and sleep in!

- 10. Chinese gift-giving taboos

It was mentioned above that you should bring gifts when paying visits. It’s the thought that counts, but some gifts are forbidden.

- Clocks are the worst gifts. The word for clock is a homophone (sounds like) “the funeral ritual”. Also, clocks and watches are items that show that time is running out.

- Items associated with funerals – handkerchiefs, towels, chrysanthemums, items colored white and black.

- Sharp objects that symbolize cutting a tie (i.e. scissors and knives).

- Items that symbolize that you want to walk away from a relationship (examples: shoes and sandals)

- Mirrors

- Homonyms for unpleasant topics (examples:green hats because “wear a green hat” sounds like “cuckold”, “handkerchief” sounds like “goodbye”, “pear” sounds like “separate”, and “umbrella” sounds like “disperse”).

Some regions have their own local taboos too. For example, in Mandarin, “apple” (苹果) is pronounced píng guǒ. But in Shanghainese, it is bing1 gu, which sounds like “passed away from sickness.”

These don’t just apply to the Spring Festival, so keep it in the back of your mind!

For the Spring Festival, these rules may seem excessive. Especially when you add in the cultural norms, customs and manners. But like a parent would say, they are all for your own good. Formed over thousands of years, these taboos embody the beliefs, wishes and worries of the Chinese people.

Foods For The New Year

Dishes may vary slightly according to regional and family customs. Dumplings (gau ji) are more commonly served in the north of China, while Hong Kong families often go for a dim sum meal.

Food symbolism goes back centuries in China, and is taken very seriously on special occasions such as Lunar New Year. All food items have their symbolic meanings which, for Hongkongers, are often derived from their Cantonese homonyms. For instance, the Cantonese word for lettuce – sang choi – sounds very similar to the phrase which means “growing wealth”. Of course, nothing considered “unlucky” is allowed near the dining table.

By carefully choosing the menu in this way, families will supposedly be able to increase their luck and manifest their wishes for the coming year, whether those be earning more money or having more children.

Red meat is not served and one is careful not to serve or eat from a chipped or cracked plate. Fish is eaten to ensure long life and good fortune. Red dates bring the hope for prosperity, melon seeds for proliferation, and lotus seeds means the family will prosper through time. Oranges and tangerines symbolize wealth and good fortune. Nian gao, the New Year’s Cake is always served. It is believed that the higher the cake rises the better the year will be. When company stops by a “prosperity tray” is served. The tray has eight sides (another symbol of prosperity) and is filled with goodies like red dates, melon seeds, cookies, and New Year Cakes.

Here the origins of some traditional Chinese festival foods and their often quirky symbolic meanings.

- Lettuce for the lion dance

No traditional Lunar New Year celebration is complete without the famous lion dance, which is thought to bring good luck and ward off evil spirits. Performers wearing the traditional lion costume normally dance through the streets to the sound of gongs and drums. When the lion briefly stops at houses and businesses along the way, it will “eat” lettuce that is hung up outside the doors, since the humble vegetable symbolizes “growing fortune”. Inside the head of the lettuce will often be a red envelope, further emphasizing its significance.

- Dried oysters and ‘hair vegetable’ stir-fry

This unusual but lucky dish is named ho see fat choy in Cantonese, which sounds a lot like the words meaning “flourishing business”. For an extra dose of luck, ho see (oyster) on its own sounds similar to the Cantonese for “good things” or “good business”, while fat choy (hair vegetable) sounds similar to “prosperity”, as in the traditional Lunar New Year greeting kung hei fat choi. What’s more, the expensive “hair vegetable”, which looks like strands of black hair, is actually a type of fungus. But that doesn’t put off Cantonese restaurants from serving the auspicious dish at Lunar New Year.

- Egg noodles, or yi mein

This classic dish of stir-fried egg noodles is often served at formal dinners during Lunar New Year and other festivals, as it symbolises longevity. The chef must not cut the noodle strands to preserve their length. For this reason, yi mein is often eaten at birthday celebrations too – kind of like the Chinese equivalent of a candle-lit birthday cake.

- Glutinous rice cake, or neen go

The Cantonese term for this traditional sticky treat sounds the same as the literal words “year high”, which symbolize the promise of a better year to come. Families may eat this for several reasons: wanting to have a higher income, higher social status or even more children. Rice cake can be cooked in a variety of ways, and can be sweet or savory. Historical records date the yearly custom to at least 1,000 years ago, in the days of the Liao dynasty (AD907-1125). If there’s one thing that is unmissable from every family’s Lunar New Year feast in all parts of China and Hong Kong, it must be this dish.

- ‘Basin food’, or poon choi

Originating from the walled villages of the New Territories, this traditional celebratory dish soon spread throughout Hong Kong and later China. Legend has it that the early settlers in the New Territories would pool together their most prized ingredients – meat and seafood – in a big wooden washbasin and cook them to be served to the whole village. The communal dish required huge efforts of co-ordination and manpower to cook, so it quickly became associated with celebrations and religious rituals. Each village had its own secret poon choi recipe consisting of various ingredients layered in a particular order in the pot, but the dish is now found in most Cantonese restaurants on special occasions.

- Lotus root soup, or leen gnau tong

The fleshy, tuber-like roots of the lotus flower have been a staple of Chinese cooking for millennia, and traditionally symbolise “abundance”, since the Cantonese term sounds like “having [money] year after year”. The ingredient is also prized for its supposed “cooling” effect on the body, according to traditional Chinese medicine. Lotus root soup, or alternatively stir-fried lotus root, is commonly eaten at Lunar New Year for these reasons.

- Dim sum

Another Cantonese food tradition that is now common in the West is dim sum. The phrase literally means “a light touch of the heart” or “a little bit of heart”. This reflects the care and attention put into each bite-sized dish that is shared between the table, such as har gau (shrimp dumplings), various types of filled buns, and cheung fun (rice noodle rolls). Like a Chinese take on brunch, dim sum is often served at lengthy afternoon yum cha sessions in tea houses. But Hongkongers often go for an even more lavish version of this meal around Lunar New Year.

Auspicious Greetings

The Chinese New Year is often accompanied by loud, enthusiastic greetings, often referred to as auspicious words or phrases. New Year couplets printed in gold letters on bright red paper is another way of expressing auspicious new year wishes. The most common auspicious greetings and sayings consist of four characters, such as the following:

- 金玉滿堂 Jīnyùmǎntáng –

“May your wealth [gold and jade] come to fill a hall” - 大展鴻圖 Dàzhǎnhóngtú –

“May you realize your ambitions” - 迎春接福 Yíngchúnjiēfú –

“Greet the New Year and encounter happiness” - 萬事如意 Wànshìrúyì –

“May all your wishes be fulfilled” - 吉慶有餘 Jíqìngyǒuyú –

“May your happiness be without limit” - 竹報平安 Zhúbàopíng’ān –

“May you hear [in a letter] that all is well” - 一本萬利 Yīběnwànlì –

“May a small investment bring ten-thousandfold profits” - 福壽雙全 Fúshòushuāngquán –

“May your happiness and longevity be complete” - 招財進寶 Zhāocáijìnbǎo –

“When wealth is acquired, precious objects follow”

These greetings or phrases may also be used just before children receive their red packets, when gifts are exchanged, when visiting temples, or even when tossing the shredded ingredients of yusheng particularly popular in Malaysia and Singapore. Children and their parents can also pray in the temple, in hopes of getting good blessings for the new year to come.

Sources:

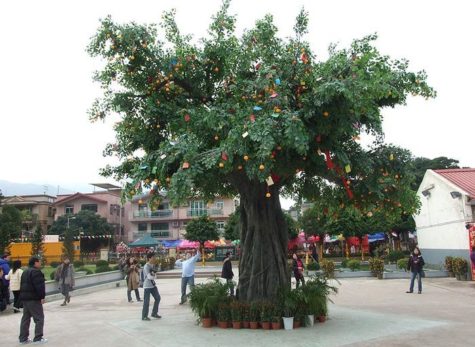

Every year, Lam Tsuen holds the Hong Kong Well-Wishing Festival. It part of the Chinese New Year celebration which attracts hundreds of thousands local citizens and tourists from all over the world. (In 2019, the festival runs from February 5 through March 3rd). Various activities at the festival include throwing wishing placard, setting wishing lanterns to make wish, joining international float exhibition, shopping in food carnival and setting lantern light to celebrate new born babies.

The Lam Tsuen Wishing Trees are a popular shrine in Hong Kong located near the Tin Hau Temple in Fong Ma Po Village, Lam Tsuen. The two banyan trees are frequented by tourists and locals during the Lunar New Year. Every year, wish-makers flood to Lam Tsuen for good fortune. The Lam Tsuen Wishing Trees are said to have the magic power to make a wish real.

The Lam Tsuen Wishing Tree was originally a camphor tree and later a redbud tree. The present Lam Tsuen Wishing Tree refers to an at least 200 year old banyan tree at the entrance of Lam Tsuen. There is also a newly planted banyan tree inside the village and a plastic Wishing Tree.

Lam Tsuen Wishing Tree has long been regarded as a deity by locals, who light candles and burn joss sticks at the root to worship the god. It is a tradition to make red or yellow papers on which people would write down their names, dates of birth and wishes, and roll the papers and tie them with weights (usually an orange) and finally toss them up onto the Wishing Tree. The paper scrolls are called “Bao Die.” Legend has it that if the “Bao Die” does not fall down, a wish would come true. Otherwise, the wish is said to be too greedy.

The Lam Tsuen Wishing Tree at the entrance was covered with “Bao Die” all the year around. As a result, it became extremely fragile. This practice was discouraged by the authorities after 12 February 2005, when one of the branches gave way and injured two people. Instead, wooden racks are set up in place for joss papers to be hung while a period of conservation is imposed to help these trees recover and flourish. Due to the lack of attractiveness of the attraction, A new plastic tree from Guangzhou was purchased in late 2009, plastic mandarin oranges are now only allowed to be tied to the branches. The tradition was able to continue since then.

There are four wishing trees in Lam Tsuen. Different trees symbolize various wishes. The first tree prays for career, academic and wealth. The second tree is for marriage and pregnancy. For the third tree, it states anything can be prayed. Yet, the fourth tree is believed to be most special. It is a fake 25-foot wishing tree made of plastic. Most people make wishes on the plastic Wishing Tree. This plastic fake wishing tree allows worshipers to throw their wishes to the tree.

A traditional “ Bao Die “ includes an orange and it ties with a yellow paper. Worshipers can write their name, date of birth and wishes on the yellow paper and throw it to the wishing tree. If you can successfully throw the “Bao die” and it hangs up on the tree or its branches, the myth said your wishes can come true. However, if it drops, the legend reckoned that your wishes are too greedy. But still, if the “wishes” drop, do not give up, try more and keep throwing until you make your wishes success.

There are lots of interesting stories about Lam Tsuen Wishing Tree. Lam Tsuen wishing tree was an ordinary camphor tree where a tablet for enshrining and worshipping Pak Kung was placed. As years passed, the branches and leaves gradually withered and eventually it became a hollow tree. People started to believe that Lam Tsuen wishing tree was magical after a legend: a man whose son had had a slow learning progress made a wish to a hollow tree. After that, his son’s academic performance has shown drastic improvement.

Another popular legend goes that the original wishing tree was huge with holes in the trunk. When people came to worship it and burn joss sticks, there would be oils flowing down form the holes. Unfortunately, the tree broke down after a fire accident. Surprisingly, before its death, two redbud blossoms appeared on the tree and grew rapidly. Soon the two blossoms were even bigger than the whole wishing tree.

In 2011, a Wishing Well was founded beside the wishing trees. The Wishing Well is a rectangle water channel flanked by glass with a length of 4 meters. The public can write down their wishes on paper, put it into a lotus-like lamp and drift the lamp on water to make a wish.

Sources:

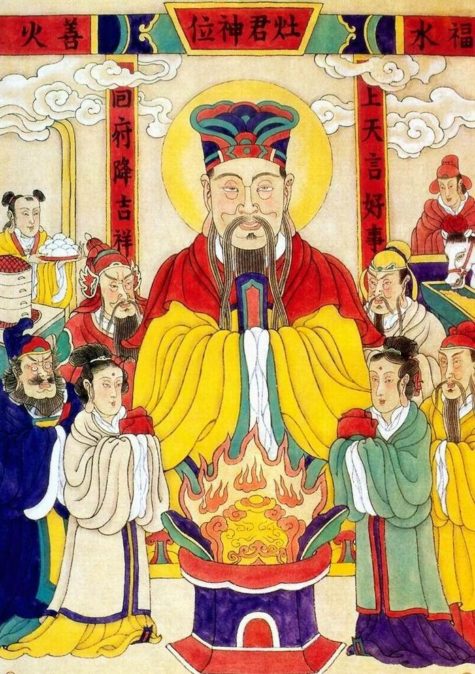

The Xiao Nian Festival (Little New Year) or the Kitchen God Festival occurs approximately a week before the Chinese New Year. The dates vary depending on the region, and from year to year.

It is believed that people in northern China celebrate it on the twenty-third day of the twelfth lunar month, while the people in southern China celebrate it on the twenty-fourth. Along with location, traditionally the date may also be determined by one’s Profession. For example, “feudal officials made their offerings to the Kitchen God on the twenty-third, the common people on the twenty-fourth, and coastal fishing people on the twenty-fifth”.

In 2019, in Taiwan, the festival will be celebrated on January 29.

It is believed that just before Chinese New Year, the Kitchen God returns to Heaven to report the activities of every household over the past year to Yu Huang, the Jade Emperor. Once in Heaven, the words of the Kitchen God influences the amount of prosperity and abundance that each family will have bestowed on them in the new year. The Jade Emperor, emperor of the heavens, either rewards or punishes a family based on Zao Jun’s yearly report.

In order to ensure that the Kitchen God speaks sweetly of the family, offerings of incense and bowls of ‘sweet treats’ such as ripe melons, honey, glutinous cakes, and sugar candies are presented for his delight before his image is burned and his journey begins.

Gold and silver ‘ingots’ fashioned from paper are also offered, and little paper-mache sedan chairs are sometimes provided to offer comfort on the journey to Heaven.

On this day, the lips of Zao Jun’s paper effigy are often smeared with honey to sweeten his words to Yu Huang (Jade Emperor), or to keep his lips stuck together. Incense and candles are lit around the house. Sticky sweets are left for the Kitchen God, usually on an alter or shrine. The stickier the candy the better, so the god’s mouth sticks closed and he can’t speak poorly of the family. According to custom, men must leave the sweets.

To send the god on his way, his picture is taken outside and the effigy is burned and replaced by a new one on Chinese New Year’s Day. Firecrackers are often lit as well, to speed him on his way to heaven. If the household has a statue or a nameplate of Zao Jun it will be taken down and cleaned on this day for the new year.

In days leading up to the Lunar New Year, people clean their houses, decorate their homes with paper cuttings, couplets and written blessings, and prepare festival food. After the cleaning is done, homes are decorated in red papercuts and posters, and fresh flowers.

In order to establish a fresh beginning in the New Year, families must be organized both within their family unit, in their home, and around their yard. This custom of a thorough house cleaning and yard cleaning is another popular custom during “Little New Year”. It is believed that in order for ghosts and deities to depart to Heaven, both their homes and “persons” must be cleansed. Lastly, the old decorations are taken down, and there are new posters and decorations put up for the following Spring Festival.

According to traditional Chinese culture, the kitchen god returns from heaven on the eve of Spring Festival, so the sacrifices for the god are served until the day he returns.

How Zao Jun Became The Kitchen God

Though there are many stories on how Zao Jun became the Kitchen God, the most popular one dates back to around the 2nd Century BC. Zao Jun was originally a mortal man living on earth whose name was Zhang Lang. He eventually became married to a virtuous woman, but ended up falling in love with a younger woman. He left his wife to be with this younger woman and, as punishment for this adulterous act, the heavens afflicted him with ill-fortune. He became blind, and his young lover abandoned him, leaving him to resort to begging to support himself.

Once, while begging for alms, he happened across the house of his former wife. Being blind, he did not recognize her. Despite his shoddy treatment of her, she took pity on him and invited him in. She cooked him a fabulous meal and tended to him lovingly; he then related his story to her. As he shared his story, Zhang Lang became overwhelmed with self-pity and the pain of his error and began to weep.

Upon hearing him apologize, Zhang’s former wife told him to open his eyes and his vision was restored. Recognizing the wife he had abandoned, Zhang felt such shame that he threw himself into the kitchen hearth, not realizing that it was lit. His former wife attempted to save him, but all she managed to salvage was one of his legs.

The devoted woman then created a shrine to her former husband above the fireplace, which began Zao Jun’s association with the stove in Chinese homes. To this day, a fire poker is sometimes referred to as “Zhang Lang’s Leg”.

Alternatively, there is another tale where Zao Jun was a man so poor he was forced to sell his wife. Years later he unwittingly became a servant in the house of her new husband. Taking pity on him she baked him some cakes into which she had hidden money, but he failed to notice this and sold the cakes for a pittance. When he realized what he had done he took his own life in despair.

In both stories Heaven takes pity on Zhang Lang’s tragic story. Instead of becoming a vampirish hopping corpse, the usual fate of suicides, he was made the god of the Kitchen, and was reunited with his wife.

Another possible story of the “Stove god” is believed to have appeared soon after the invention of the brick stove. The Kitchen God was originally believed to have resided in the stove and only later took on human form.

During the Han Dynasty, it is believed that a poor farmer named Yin Zifang, was surprised by the Kitchen God who appeared on Lunar New Year as he was cooking his breakfast. Yin Zifang decided to sacrifice his only yellow sheep. In doing so, he became rich and decided that every winter he would sacrifice one yellow sheep in order to display his deep gratitude.

Source:

The Mid-Autumn Festival, also known as the Moon Festival, is a popular East Asian celebration of abundance and togetherness, dating back over 3,000 years to China’s Zhou Dynasty. In Malaysia and Singapore, it is also sometimes referred to as the Lantern Festival or “Mooncake Festival.”

The Mid-Autumn Festival falls on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month of the Chinese calendar (usually around mid- or late-September in the Gregorian calendar), a date that parallels the Autumn Equinox of the solar calendar. The moon festival is celebrated on the full moon closest to the Autumn Equinox, which sometimes falls in October. This is the ideal time, when the moon is at its fullest and brightest, to celebrate the abundance of the summer’s harvest. The traditional food of this festival is the mooncake, of which there are many different varieties.

The Moon Festival is full of legendary stories. Legend says that Chang Er flew to the moon, where she has lived ever since. You might see her dancing on the moon during the Moon Festival. The Moon Festival is also an occasion for family reunions. When the full moon rises, families get together to watch the full moon, eat moon cakes, and sing moon poems. With the full moon, the legend, the family and the poems, you can’t help thinking that this is really a perfect world. That is why the Chinese are so fond of the Moon Festival.

The Moon Festival is also a romantic one. A perfect night for the festival is if it is a quiet night without a silk of cloud and with a little mild breeze from the sea. Lovers spend such a romatic night together tasting the delicious moon cake with some wine while watching the full moon. Even for a couple who can’t be together, they can still enjoy the night by watching the moon at the same time so it seems that they are together at that hour. A great number of poetry has been devoted to this romantic festival. Hope the Moon Festival will bring you happiness.

Farmers celebrate the end of the summer harvesting season on this date. Traditionally, on this day, Chinese family members and friends will gather to admire the bright mid-autumn harvest moon, and eat moon cakes and pomeloes together. Accompanying the celebration, there are additional cultural or regional customs, such as:

- Eating moon cakes outside under the moon

- Putting pomelo rinds on one’s head

- Carrying brightly lit lanterns

- Burning incense in reverence to deities including Chang’e

- Planting Mid-Autumn trees

- Collecting dandelion leaves and distributing them evenly among family members

- Lighting lanterns on towers

- Fire Dragon Dances

- Shops selling mooncakes, before the festival, often display pictures of Chang’e floating to the moon.

Stories behind the festival can be found at Widdershins:

The Moon Cake Uprising

In late Yuan Dynasty (1271 – 1368 AD), people in many parts of the country could not bear the cruel rule of the government and rose in revolt. Zhu Yuanzhang, founder of Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644 AD), united the different resistance forces and wanted to organize an uprising. However, due to the narrow search by government, it was very difficult to pass messages.

The counselor Liu Bowen later though out the great idea of hiding notes with “uprise on the night of August 15th” in moon cakes and had them sent to different resistance forces. The uprising turned to be very successful and Zhu was so happy that he awarded his subjects with moon cakes on the following Mid-Autumn Festival. Since then, eating moon cakes has been a custom on Mid-Autumn Festival.

Sources: Wikipedia and Travel China Guide

The seventh lunar month in the traditional Chinese calendar is called Ghost Month. These dates vary from year to year, in 2017, Ghost Month runs from August 28 to September 19, and the Ghost Festival is on Sept 5.

On the first day of the month, the Gates of Hell are sprung open to allow ghosts and spirits access to the world of the living. The spirits spend the month visiting their families, feasting and and looking for victims.

There are many taboos in the Ghost Month. For example, do not wear the clothes with your name, do not pat other people on the shoulder, do not whistle, children and senior citizens should not go out at night.

There are three important days during Ghost Month. On the first day of the month, ancestors are honored with offerings of food, incense, and ghost money – paper money which is burned so the spirits can use it. These offerings are done at makeshift altars set up on sidewalks outside the house.

Almost as important as honoring your ancestors, offerings to ghosts without families must be made, so that they will not cause you any harm. Ghost month is the most dangerous time of the year, and malevolent spirits are on the look out to capture souls.

This makes ghost month a bad time to do activities such as evening strolls, traveling, moving house, or starting a new business. Many people avoid swimming during ghost month, since there are many spirits in the water which can try to drown you.

The 15th day of the month is Ghost Festival, sometimes called Hungry Ghost Festival. The Mandarin name of this festival is zhōng yuán jié (中元節 / 中元节). This is the day when the spirits are in high gear. It’s important to give them a sumptuous feast, to please them and to bring luck to the family. Taoists and Buddhists perform ceremonies on this day to ease the sufferings of the deceased.

The last day of the month is when the Gates of Hell are closed up again. The chants of Taoist priests inform the spirits that it’s time to return, and as they are confined once again to the underworld, they let out an unearthly wail of lament.

The story:

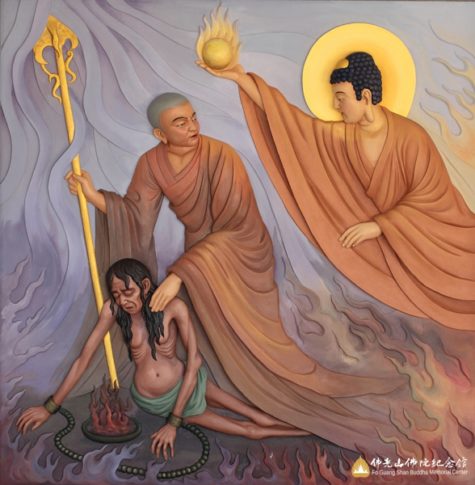

The idea of a feast for the ghosts comes from a story of Buddhism. Moggallana was one of Buddha Shakyamuni’s best students. He had various supernormal powers and owned the divine eyes. One day, he saw his deceased mother had been born among hungry ghosts.

He went down the Hell, filled a bowl with food to provide for his mother. Before reaching his mother’s month, the food turned into burning coals which couldn’t be eaten. Moggallana cried sorrowfully and asked for help from Buddha.

Buddha said the sins of his mother were deep and firmly rooted, and couldn’t be forgiven just using the divine power. It would require the combined power of thousand monks to get rid of her sins. Buddha told Moggallana:

“the 15th day of the 7th lunar month is the Pavarana Day for the assembled monks of all directions. You should prepare an offering of clean basins full of hundreds of flavors and the five fruits, and other offerings of incense, oil, lamp, candle… to the greatly virtuous assembled monks. Your present parents and parents of seven generations will escape from sufferings.”

Following Buddha’s instructions, Moggallana’s mother obtained liberation from sufferings as a hungry ghost by receiving the power of the merit and virtue form the awesome spiritual power of assembled monks on 15th day of the 7th lunar month.

Today, similar rituals are held in the Buddhism temples on this day for the deliverance of all suffering spirits.

Found at: Mandarin.About.Com and other sources

Although Midsummer Day occurs at the summer solstice, or what we think of as the beginning of summer, to the farmer it is the midpoint of the growing season, halfway between planting and harvesting, and an occasion for celebration.

The most common other names for this holiday are the Summer Solstice or Midsummer, and it celebrates the arrival of Summer, when the hours of daylight are longest. The Sun is now at the highest point before beginning its slide into darkness.

Celebrating Midsummer Day

Although it’s also the feast day of St. John the Baptist, it features pagan traditions such as bonfires, fire walking, and a carnival atmosphere, all of which took place on Midsummer Eve. Certainly, it’s a night of magic and soothsaying as well, for as Washington Irving said, this is a time “when it is well known all kinds of ghosts, goblins, and fairies become visible and walk abroad.” After Midsummer Day, the days shorten.

In Sweden and Norway at the Solstice, people made wheels of fortune. Some of the wheels were wrapped in straw, set on fire, and rolled down hill. Other wheels were decorated and kept. These were used in two ways: One, the wheel was rolled away from a person to take away misfortunes; two, it was rolled toward a person to bring all kinds of good fortune.

Variations on the Midsummer celebrations:

People around the world have observed spiritual and religious seasonal days of celebration during the month of June. Most have been religious holy days which are linked in some way to the summer solstice.

- Scottish Pecti-Witans celebrate Feill-Sheathain on July 5th.

- In the Italian tradition of Aridian Strega, this Sabbat (Strega Witches call them Treguendas rather than Sabbats) is known as Summer Fest – La Festa dell’Estate.

- Scandinavians celebrate this holiday at a later date and call it Thing-Tide.

- In England, June 21st is “The Day of Cerridwen and Her Cauldron”.

- In Ireland, this day is dedicated to the faery goddess Aine of Knockaine.

- June 21st is “The Day of the Green Man” in Northern Europe.

In Lithuanian tradition, the dew on Midsummer Day was said to make young girls beautiful and old people look younger. It was also thought that walking barefoot in the dew would keep one’s skin from getting chapped.

It was customary to honor all men named John on this day by fixing wreaths of oak leaves around their doors. This is usually done in secret, and John must guess who did it or catch the person in the act, in which case he must give the person a treat.

Midsummer Celebrations in Ancient Times:

The solstice itself has remained a special moment of the annual cycle of the year since Neolithic times. The concentration of the observance is not on the day as we reckon it, commencing at midnight or at dawn, but the pre-Christian beginning of the day, which falls on the previous eve. Other names for this time in the Wheel of the Year include:

- Alban Heruin (Caledonii or the Druids)

- Alban Hefin (Anglo-Saxon Tradition)

- Sun Blessing, Gathering Day (Welsh)

- Whit Sunday, Whitsuntide (Old English)

- Vestalia (Ancient Roman)

- Feast of Epona (Ancient Gaulish)

- All-Couple’s Day (Greek)

Ancient Celts: Druids, the priestly/professional/diplomatic corps in Celtic countries, celebrated Alban Heruin (“Light of the Shore”). It was midway between the spring Equinox (Alban Eiler; “Light of the Earth”) and the fall Equinox (Alban Elfed; “Light of the Water”). “This midsummer festival celebrates the apex of Light, sometimes symbolized in the crowning of the Oak King, God of the waxing year. At his crowning, the Oak King falls to his darker aspect, the Holly King, God of the waning year…” The days following Alban Heruin form the waning part of the year because the days become shorter.

Ancient China: Their summer solstice ceremony celebrated the earth, the feminine, and the yin forces. It complemented the winter solstice which celebrated the heavens, masculinity and yang forces.

Ancient Egypt:In Ancient Egypt, summer solstice was the most important day of the year. The sun was at its highest and the Nile River was beginning to rise. Special ceremonies were held to honor the Goddess Isis. Egyptians believed that Isis was mourning for her dead husband, Osiris, and that her tears made the Nile rise and well over. Accurately predicting the floods was of such vital importance that the appearance of Sirius, which occurs around the time of the summer solstice, was recognized as the beginning of the Egyptian New Year.

Ancient Gaul: The Midsummer celebration was called Feast of Epona, named after a mare goddess who personified fertility, sovereignty and agriculture. She was portrayed as a woman riding a mare.

Ancient Germanic, Slav and Celtic tribes in Europe: Ancient Pagans celebrated Midsummer with bonfires. “It was the night of fire festivals and of love magic, of love oracles and divination. It had to do with lovers and predictions, when pairs of lovers would jump through the luck-bringing flames…” It was believed that the crops would grow as high as the couples were able to jump. Through the fire’s power, “…maidens would find out about their future husband, and spirits and demons were banished.” Another function of bonfires was to generate sympathetic magic: giving a boost to the sun’s energy so that it would remain potent throughout the rest of the growing season and guarantee a plentiful harvest.

Ancient Rome: The festival of Vestalia lasted from June 7 to June 15. It was held in honor of the Roman Goddess of the hearth, Vesta. Married women were able to enter the shrine of Vesta during the festival. At other times of the year, only the vestal virgins were permitted inside.

Ancient Sweden: A Midsummer tree was set up and decorated in each town. The villagers danced around it. Women and girls would customarily bathe in the local river. This was a magical ritual, intended to bring rain for the crops.

Information collected from various sources

The seventh day of the Chinese New Year, traditionally known as Rénrì (人日, the common man’s birthday), is the day when everyone grows one year older. In some overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia, such as Malaysia and Singapore, it is also the day when tossed raw fish salad, yusheng, is eaten for continued wealth and prosperity.

This day is filled with omens about human fate. For example, any person or animal born on this day is considered doubly blessed and destined for prosperity. So, consider taking out a divination tool today and seeing what fate holds for you.

In Chinese mythology, Nüwa is the goddess who created the world. She created the animals on different days, and human beings on the seventh day after the creation of the world. The order of creation is as follows:

- First of zhengyue: Chicken

- Second of zhengyue: Dog

- Third of zhengyue: Boar

- Fourth of zhengyue: Sheep

- Fifth of zhengyue: Cow

- Sixth of zhengyue: Horse

- Seventh of zhengyue: Human.

Hence, Chinese tradition has set the first day of zhengyue as the “birthday” of the chicken, the second day of zhengyue as the “birthday” of the dog, etc. And the seventh day of zhengyue is viewed as the common “birthday” of all human beings.

To generate Nüwa’s luck or organizational skills in your life, make and carry a clay Nüwa charm. Get some modeling clay from a toy store (if possible, choose a color that suits your goal, like green for money). If you can’t get clay, bubblegum will work, too. Shape this into a symbol of your goal, saying:

From Nüwa blessings poured,

Luck and order be restored.

Renri is the day, when all common men are growing a year older and the day is celebrated with certain foods according to the origin of the people. The ingredients of the dishes have a symbolic meaning and they should enhance health.

To honour Nüwa’s creation of animals either vegetable dishes will be eaten or a raw fish and vegetable salad called yusheng. Yusheng literally means “raw fish” but since “fish (鱼)” is commonly conflated with its homophone “abundance (余)”, Yúshēng (鱼生) is interpreted as a homonym for Yúshēng (余升) meaning an increase in abundance. Therefore, yusheng is considered a symbol of abundance, prosperity and vigor.

Almost no Chinese celebrate on this day. Some people just eat potatoes with angel hair noodle. The long noodle stands for longevity. In the past, seven vegetables which can repel the evil spirits and sickness away were eaten. They are as follows:

- Celery, Shepherd’s Purse Spinach, Green Onion, Garlic, Mugwort and Colewort

Ancient Chinese had a tradition of wearing head ornaments called rensheng, which were made of ribbon or gold and represented humans. People also climbed mountains and composed poems. Emperors after the Tang dynasty granted ribbon rensheng to their subjects and held festivities with them. If there were good weather on Renri, it was considered that people will have a year of peace and prosperity.

Fireworks and huapao are lit, so Renri celebrates the “birthday” of fire as well.

Since the first days of zhengyue are considered “birthdays” of different animals, Chinese people avoid killing the animals on their respective birthdays and punishing prisoners on Renri.

Nowadays in zhengyue, Renri is celebrated as part of the Chinese New Year. Chinese people prepare lucky food in the new year, where the “seven vegetable soup,” “seven vegetable congee” and “jidi congee” are specially prepared for Renri. Malaysian and Singaporean Chinese use the “seven-colored raw fish” instead of the “seven vegetable soup”.

In Japan, Renri is called Jinjitsu. It is one of the five seasonal festivals. It is celebrated on January 7. It is also known as Nanakusa no sekku, “the feast of seven herbs”, from the custom of eating seven-herb kayu to ensure good health for the coming year.

The celebration of the feast in Japan was moved from the seventh day of the first lunar month to the seventh day of January during the Meiji period, when Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar.

Sources: 365 Goddess and wikipedia

May 25 is the Chinese and Japanese Celebration of the Tao – The Mother of the World. In Taoism, a great spiritual tradition of the East, the Goddess is perceived as the mother of the world, the Way to the heart.

On this day, burn incense to the Goddess and meditate on Divine Harmony. The whole philosophy of the Way (or Tao) in Chinese mysticism is essentially a respect for the truth in nature and her ways. It is also a belief that people must live in harmony with the Way and not destroy or interfere but, rather, flow with it. This, as they say, is:

“Holding fast to the Mother. She is the origin of all things and beings, born before heaven and earth. Silent and void she stands alone, does not change, goes round and does not weary, and is capable of being the mother of the world.”

~Tao Teh Ching

From: The Grandmother of Time