Spirits of the Dead

The Dance of the Devils (La danza de los diablos) is a dance performed in Costa Chica, the Pacific coast of Guerrero and Oaxaca in Mexico. As part of the ‘Day of the Dead’ festivities celebrated on the last days of October and the first days of November in Mexico. Its purpose is not so much to terrify however as to amuse and draw the community together while paying reverence to the spirits of the dead on the Day of the Dead.

Men dressed in rags and high boots perform the Dance of the Devils in Afro-Mexican communities. During these celebrations young men dress up as cowboys or as dead people, in which case they wear dusty clothes covered with terrain (to represent the passage of time and the fact of being buried underground). Their faces are covered with masks made of leather or paper with long beards and hair. A black beard represents a young devil, a white beard represents an old one. A small pair of goat or deer horns crowns the mask.

The men dance through different villages on All Souls Day, making noise and playing with children and young people by flogging them with a whip.

An elder diablo called el Terron, and a female diabla called la Minga, who carries a baby doll, lead the dancers. The elder diablo plays and whips the other diablos into dancing and chases la Minga around with the whip because she interrupts the concentration of the devil dancers. One way that la Minga attempts to disrupt the other dancers is by seduction, the Minga also tries to give her doll, which is a symbol of her productive power, to the dancers or to anyone in the audience, seeking a father to her ‘baby’.

The face of the men performing the dance is covered with a leather deer mask with horns and An elder devil, called Tenango, whips the other devils during this performance. Groups of 24 dancers (the devils) stomp and twirl in rows or circles along the streets; eventually, they stop at the houses where the owner gives them money or food for dancing.

Origins of the Dance of the Devils:

The Dance of the Devils is part of the ceremonial commemoration of the dead. It is a celebration of colonial origin, which was introduced by the black people of the Costa Chica of Guerrero and Oaxaca, who were brought there as slaves by the Spanish colonizers to work in mines, cotton plantations and cattle ranches.

From Río Grande, in the town of Tututepec, on the Oaxacan coast, to Tenango, in the municipality of Azoyú, to the north, this dance recalls the past times when ranchers or cowboys used the whip as well as trumpet to groups of wild cattle in order to force them to cross the Sierra Madre del Sur, to reach the plateau and sell the animals.

The Devils in the Mexican dance also use the whip, and behave according to the cowboy stereotype, that is, as brave and strong man. This performance, however, is also a historical memory, which becomes a ritual memory to the black population which was an intermediate caste, between the indigenous and the white land owners.

The black population who arrived in Mexico from very different lands such as Africa and the Antilles, bringing different languages and cultures, could not recreate a black culture of African traits, as could happen instead, to various degrees, in other Afro-American regions. These people therefore in their segregation from festivities and public celebrations organized by the masters of the haciendas, used to perform their own festivities secretly, by performing rituals to their African gods, playing drums and dancing.

At the same time, however, they borrowed elements of some indigenous and Catholic traditions and readopted them – with imagination and joy – to overcome the pain of domination and the humiliation of banishment.

It is no coincidence that the celebration of their ancestors is performed through the cowboy/devil figure. In this dance the ritual action harmonizes gestures and words. Devils are the dead who revive to do mischief, to steal, to sow fear and laughter. The dance could also be called the ‘Devil’s Game’, a game designed to laugh at the forbidden: a capataz (a boss), a bad mother, or a violent and bossy father.

The function of the Dance of the Devils, from a social aspect, is to cleanse and protect the community from spirits that carry evil energy. It can be viewed a way to control evil. In a sense, the dance is used to call the tono spirits of the ancestors to heal the community similar to the way an individual might be healed; the masks and the boite drum call the spirits and the dance is the mode of healing. Trance possession, another traditional healing mode, is also part of these dances, as a means to form a connection between the spiritual and material.

The dancers use their bodies to bring the spirits and form a bond between them and the community. “As they dance, they create an aura, which begins to rise and cover everyone who is sitting there. ” Even the children will come and sit quietly and watch. The force, she says, starts in the dancers’ hands and continues through their feet, legs, hips, shoulders, and faces until they are entirely transformed. The wearing of the tono masks allows them to achieve a more powerful transformation.

About The Dance:

The dance itself is strikingly similar to the egungun dances of West Africa; the performance is a form of ancestor reverence, and similar dances that may be seen throughout the Diaspora (the dispersion of the people from their original homeland). While the Dance of the Devils occurs within a context that includes European and Native influences, the core of the dance, its meaning and specific elements, are African.

The Dance of the Devils can be traced to Europe during the Middle Ages, but according to an Afro-Mestizo elder, the devils are spirits of the dead and not devils in search of souls. They are actually ancestral spirits whose presence is celebrated and encouraged. Similar to a dance performed by the Abakua in Cuba, dressing as a diablo (devil) symbolizes the willingness to allow the spirit to possess your body.

The egungun masquerades of West Africa are, like the Dance of the Devils, performed as part of a feast of the dead. Masks are worn which represent the dead, symbolically, but not as individual persons; flogging with whips is intended to promote growth and maturity in young men and fertility in women. The egungun dances were a strong social force in the societies where they originated, especially in times of unrest or external threat.

Another similarity is that while only men generally perform the dances, there is often at least one woman who either participates on some level or teaches the dance.

It has been suggested that the presence of the whip is a reference to the relationship between the former slaves and their overseers. However, the presence of flogging in the egungun dances of West Africa, when compared to Nana Minga and her baby, suggests that flogging is another African retention and bears its original symbolic meaning of fertility and protection against evil spiritual energy.

The dance being performed on the Day of the Dead leads one to think that the dance relates to the supernatural world of the spirits. The fact that the dancers dress in cowboy clothes and wear masks made of horse hair may be interpreted to mean that the dance represents the spirits of dead cowboys, the employment of many of the Afro-Mestizos cimarron ancestors. However, the masks, which appear animal-like, may in fact represent the tono spirits of ancestors, an idea supported by the presence of the boite drum.

The boite or bute, is a large gourd with a goatskin head; the drum is played by moving a stick through a hole in the center to create a vibration, not by striking. It is very similar to a drum used by the Abakua, an all-male secret society in Cuba, and is described in a similar fashion, as having the voice of a big cat, a leopard or jaguar, because of the roaring sound it makes.

When attempting to heal someone of sickness Afro-Mestizos call the animal tono of the sick person. Finding the person’s tono is a way to determine if the sickness is caused by the animal’s death. Healers in attempt to cure a person called the leopard, using the roaring sound of the boite drum to simulate the voice of the big cat.

Sources:

May 26 is World Dracula Day which commemorates Bram Stoker’s Gothic horror novel Dracula, which was first published on May 26 in 1897, by Archibald Constable and Company in Britain. It sold for six shillings and came bound in yellow cloth with red lettering. It was first printed in the United States two years later, by Doubleday & McClure of New York City. Although not the first novel about vampires, it became a model for the genre, and laid the foundation for future vampire stories, with its introduction of the character Count Dracula.

The quintessential vampire, Count Dracula has inspired tens of films and stories the world over, not to mention the virtual immortality of the character during as a beloved Halloween character. For all of these reasons, it’s undeniable that this icon of horror more than deserves his own little holiday so the world can show its appreciation for his contributions to the worlds of cinema and literature over the centuries. So put on your fangs, and let’s sink out teeth right into this, shall we?

About The Book

The book follows (spoiler alert!) an English lawyer named Jonathan Harker as he travels to Transylvania to meet Count Dracula at his castle, Castle Dracula. To Harker, Dracula appears pale and off-kilter. The strangeness of Dracula is more apparent after he lunges at Harker’s throat after Harker cuts himself while shaving. Harker eventually finds out that Dracula is a vampire who needs to drink human blood to survive. Afterward, Dracula locks Harker in the castle and flees to England with 50 boxes of dirt (it is believed he needs dirt from his home country to stay healthy). As Dracula heads to England to search for new blood, Harker eventually escapes from the castle.

Meanwhile, Mina, Harker’s fiancée, is visiting her friend Lucy in England. One night, Mina finds Lucy sleepwalking by a graveyard. Mina believes she sees a creature hovering over Lucy for a moment, and then notices two red marks on Lucy’s neck. Lucy becomes sick over the next few days and is then cared for by a Dr. Seward and by Dr. Abraham Van Helsing, before eventually dying. Afterward, strange reports begin surfacing that a creature has been attacking children in the area.

Jonathan Harker and Mina are reunited and married. Harker tells Dr. Helsing about his experience with Dracula, and Helsing then believes Lucy contracted vampirism from him and is the one attacking children. They dig up her corpse, cut off her head, put a stake through her heart, and stuff her mouth with garlic. They then turn their focus to Dracula and try to destroy his boxes of dirt. He escapes back to Transylvania, where they find him buried in the last box of dirt. They cut off his head and stab him through the heart, causing him to collapse into dust.

The Origins Of Dracula

Stoker spent years researching vampires before writing Dracula. During that time, he was particularly influenced by “Transylvanian Superstitions,” an essay by Emily Gerard that was published in 1885. Stoker worked at the Lyceum Theatre in London from 1878 to 1898. The theater was headed by Henry Irving, who Stoker based Dracula’s mannerisms on. It was even Stoker’s hope that Irving would play Dracula in a stage adaptation, but it did not happen.

According to one theory, Prince Vlad III of Wallachia (Romania) was the real-life inspiration behind Stoker’s gothic horror novel. An extremely cruel and merciless ruler, Vlad earned the nickname “Vlad the Impaler” for the many ways he tortured his opponents as well as people who betrayed him when they were captured. As can be guessed from his nickname, impaling was his favorite method of execution, and it is thought that he killed up to 100,000 people during his reign, and was infamous for the “forests” of impaled victims he left behind when he won a battle. One unsubstantiated account says that he dipped bread in his victims’ blood and ate it in front of them as they died on stakes.

Born in Transylvania in the fifteenth century, he was also called Drăculea, which means “Son of Dracul.” Indeed, his father was known as Dracul, a name that derived from the knightly order he belonged to—the Order of the Dragon (the Latin word draco means dragon). In modern Romanian, drac means “devil.”

It is believed that Stoker picked the name Dracula after learning this more modern translation. Some believe that the only connection between Vlad III and Dracula are their names. The connection of his character with vampirism was made by Bram Stoker around the 1890’s, and has become a permanent element of pop culture since then.

What does it mean?

Dracula has been interpreted in numerous ways. Some have interpreted the story as an allegory of the fear that western Europeans had of eastern Europeans coming into their area. Hence, the story of someone coming from Transylvania—in Romania—to London and wreaking havoc on its residents. This theme appeared in other novels of the time.

Some have seen the book as a reaction to the conservative and patriarchal norms of the Victorian period, and as an exploration of suppressed sexual desire. Some also have seen the book as being about the relationship between the past and future, with Dracula symbolizing a primitive past that challenges modernity.

The Historical Vampire

The concept of vampirism dates back thousands of years. The ancient Greeks, Hebrews, Egyptians and Babylonians all had legends telling hair-raising tales of demon-like undead creatures that lived off of the blood of the living.

Tales of the undead consuming the blood or flesh of living beings have been found in nearly every culture around the world for many centuries. Today we know these entities predominantly as vampires, but in ancient times, the term vampire did not exist; blood drinking and similar activities were attributed to demons or spirits who would eat flesh and drink blood; even the devil was considered synonymous with the vampire.

Almost every nation has associated blood drinking with some kind of revenant or demon, from the ghouls of Arabia to the goddess Sekhmet of Egypt. Indeed, some of these legends could have given rise to the European folklore, though they are not strictly considered vampires by historians when using today’s definitions.

Hebrews, ancient Greeks, and Romans had tales of demonic entities and blood-drinking spirits which are considered precursors to modern vampires. Despite the occurrence of vampire-like creatures in these ancient civilizations, the folklore for the entity we know today as the vampire originates almost exclusively from early 18th-century Southeastern Europe, particularly Transylvania as verbal traditions of many ethnic groups of the region were recorded and published. In most cases, vampires are revenants of evil beings, suicide victims, or witches, but can also be created by a malevolent spirit possessing a corpse or by being bitten by a vampire itself. Belief in such legends became so rife that in some areas it caused mass hysteria and even public executions of people believed to be vampires.

In India, tales of vetalas, ghoul-like beings that inhabit corpses, are found in old Sanskrit folklore. Although most vetala legends have been compiled in the Baital Pachisi, a prominent story in the Kathasaritsagara tells of King Vikramāditya and his nightly quests to capture an elusive one. The vetala is described as an undead creature who, like the bat associated with modern-day vampirism, hangs upside down on trees found on cremation grounds and cemeteries. Pishacha, the returned spirits of evil-doers or those who died insane, also bear vampiric attributes.

The Hebrew word “Alukah” (literal translation is “leech”) is synonymous with vampirism or vampires, as is “Motetz Dam” (literally, “blood sucker”). Later vampire traditions appear among diaspora Jews in Central Europe, in particular the medieval interpretation of Lilith. In common with vampires, this version of Lilith was held to be able to transform herself into an animal, usually a cat, and charm her victims into believing that she is benevolent or irresistible. However, she and her daughters usually strangle rather than drain victims, and in the Kabbalah, she retains many attributes found in vampires.

A late 17th- or early 18th-century Kabbalah document was found in one of the Ritman library’s copies of Jean de Pauly’s translation of the Zohar. The text contains two amulets, one for male (lazakhar), the other for female (lanekevah). The invocations on the amulets mention Adam, Eve, and Lilith, Chavah Rishonah and the angels—Sanoy, Sansinoy, Smangeluf, Shmari’el, and Hasdi’el. A few lines in Yiddish are shown as dialog between the prophet Elijah and Lilith, in which she has come with a host of demons to kill the mother, take her newborn and “to drink her blood, suck her bones and eat her flesh”. She informs Elijah that she will lose power if someone uses her secret names, which she reveals at the end.

Other Jewish stories depict vampires in a more traditional way. In “The Kiss of Death”, the daughter of the demon king Ashmodai snatches the breath of a man who has betrayed her, strongly reminiscent of a fatal kiss of a vampire. A rare story found in Sefer Hasidim #1465 tells of an old vampire named Astryiah who uses her hair to drain the blood from her victims. A similar tale from the same book describes staking a witch through the heart to ensure she does not come back from the dead to haunt her enemies.

More about Vampires can be found at The Powers That Be.

How to celebrate Dracula Day

Celebrating all things Dracula why not throw a party and get your friends round for the ultimate film binge. Ideas for creating the perfect atmosphere include giving your party a Gothic feel by making sure all of your decorations are either black or blood red, the table setting is rather sophisticated, everyone is dressed elegantly and wears fangs, hanging up plenty of bat and spider web decorations, and serving plenty of blood red drinks.

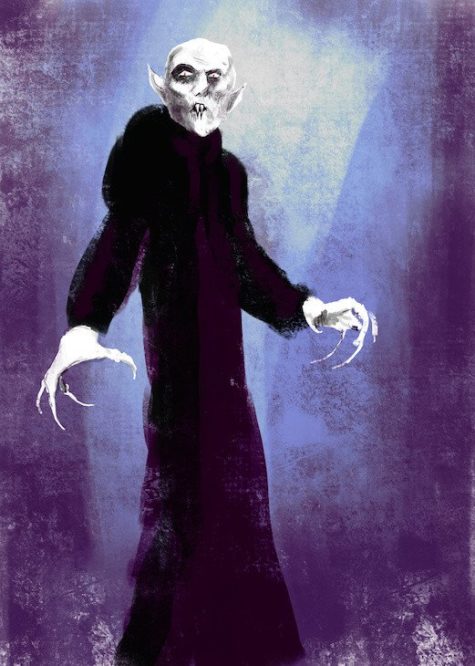

It would also be perfect to watch one or more of the classic vampire movies to have been made, such as the 1958 British classic titled simply “Dracula”, and starring the incredibly impressive Christopher Lee as the aristocratic titular character. Other movie choices include “Nosferatu”, a 1922 German expressionist horror film, and “Interview with the Vampire” starring Tom Cruise, Brad Pitt, and a young Kirsten Dunst.

If it’s something more lighthearted you’re looking for, Roman Polański’s “The Fearless Vampire Killers, or Pardon Me, But Your Teeth Are in My Neck” will keep everyone entertained. Lesser known, but equally fun movies include Suck (one of my personal favorites), and Jesus Christ Vampire Hunter.

If you don’t plan on hosting a party, that does not mean you have to miss out on Dracula day—take the time to delve into the world created by Bran Stoker in his acclaimed novel. Reading a good book has never hurt anyone, and in the era social media’s 140-character blurbs of text, it is ever more important to keep the art of literature alive.

If you’ve already read it, consider tackling Anne Rice’s “Vampire Chronicles”, a series of 11 critically acclaimed books that follow influential vampires all throughout history. Stephen King’s “Salem’s Lot”. As you can see, there is no shortage of ways to celebrate the vampires of the world this Dracula Day!

Vampire Magick:

If you get really excited about all this talk of vampires, blood, and the undead, you might even be interested in exploring spells to “become a vampire.” Alternatively, you might want to play around with some protection against vampires spells, vampire prevention spells, or even a peaceful coexistence spell. They can all be found in the Book of Shadows, and Gypsy Magick and Lore.

Sources:

When we consider the month of October and Halloween, our modern take on the Holiday is largely fun and commercially driven, celebrated with spooky costumes and all our favorite Halloween treats. However, this time of year wasn’t always celebrated with ‘trick-or-treating’. Instead, many cultures focus on the celebrations honoring those that came before us.

As we head into the Halloween season, the veil that exists between our world and that of the spiritual will has started to thin out. On Halloween night, also known as All Hallows Eve, it is said that this veil drops, allowing those in the spiritual world to move freely among us. Now, this may sound concerning, to say the least, but don’t get too worried yet. Much like us here on in this life, the spiritual world is filled with both good and not so good spirits. While there are sure to be some mischievous beings trying to bring mischief and chaos into our lives, it is believed that we will also be visited by our deceased loved ones.

The concept of the dead moving among us is the underlying concept behind the Day of the Dead or Dia de los Muertos. Often known as a holiday celebrated in Mexico, records show that these traditions can be dated back as far as the Aztecs. Spanning two days, the holiday specifically focuses on honoring our deceased loved ones, through the use of parties, parades, feasts and other celebrations. Many who celebrate also done colorful costumes and skull makeup, also known as sugar skulls, a symbol that has come to be highly recognizable in today’s pop culture.

All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day are also similar to Day of the Dead. These are celebrations embraced by Western Christianity, in which the souls of faithful Christians who have paced are honored with the placing of flowers or candles at their grave sites, and church services discussing their memory. During this time, Christians also pay tribute to the martyrs and saints.

Also known as ‘Summers End’, Samhain is the Pagan holiday celebrated at this time. While this holiday is largely associated with the celebrations of the ancient Celts, many Pagans, Wiccans and Druids will celebrate Samhain around the globe. The holiday marks the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter, however, it also includes a number of celebrations including bonfires and feasts, honoring those that came before them.

Are You Looking For Ways To Honor Your Deceased Loved Ones During This Time? Here Are A Few Ideas:

- Cook a specific meal in honor of your deceased loved one. This is a regular part of the celebrations of Day of the Dead. Those who celebrate would cook the favorite meal of their loved one to ‘share’ in celebration of their time together.

- Use meditation to allow you to open your mind and your heart to communication from your loved ones. Remember, they are moving among you and may very well be trying to let you know that they are there.

- If you do still visit the grave site of a loved one, take some time out this night to be there. Place a lit candle, a flower of your choice or some other memento to show you were there. If you feel their presence, speak aloud to them. Remember, they are moving among us.

- Light a black candle, paying tribute to the stages of life and the inevitable darkness that comes with its final stage, death. Candles are also often used as a tribute or memorial to those who have come before us. If you wish, you can carve the name of your loved one into a taper candle and burn it in honor of a specific loved one.

- Gather friends and family together and light a large bonfire. Share your favorite stories of your friends and loved ones as you feel them moving among you. You can also include their favorite food and drinks in the evening’s celebrations.

- Choose to celebrate life by giving thanks for the life you were given, and that of the family members that came before you. Make a list of all the reasons you have to be appreciative at this time.

- Set up an altar to honor the specific loved ones that hold a special place in your heart. This may include photos or objects that hold a special meaning of some form.

- Take part in an activity that meant something to a friend or loved one that you are choosing to honor. For example, if you recently lost your brother and he was highly into superhero movies, you could enjoy a movie marathon night either on your own or with other loved ones who knew him.

Source: Awareness Act

Anthesteria, held on February 11th, celebrates the maturing of the wine and the beginning of spring. It’s an Athenian festival in honor of Dionysus, god of the grape harvest, winemaking, and wine. The celebration lasted for three days in the month of Anthesterion (from the Hellenic calendar in ancient Attica).

The word Anthesteria is associated with “flower” or the “bloom” of the grape. A. W. Verrall (Journal of Hellenic Studies, xx., 1900, p. 115) wrote that it was a feast of “revocation” where the dead were recalled to the land of the living.

In ancient Greece, Anthesteria was the name of a festival during which the participants ritually expelled the Keres, evil female spirits, from their houses.

- The First Day

On the first day, called Pithoigia (opening of the casks), wine from the newly opened casks was offered to Dionysus and everyone in the household, including servants and slaves. The home and children were adorned with spring flowers.

- The Second Day

The second day, named Choës (feast of beakers), was for visiting. People dressed for the day, some even dressed as Dionysus. They spent the day visiting friends and family as well as the local drinking clubs were drinking games were held. Some folks offered wine to deceased relatives by pouring libations on the their tombs.

For the state, however, if was a formal day with secret ceremonies in one of the sanctuaries of Dionysus. The basilissa (or basilinna), wife of the archon basileus, would marry the god of wine in a special ceremony. She was assisted by fourteen Athenian matrons, called geraerae, who the basileus chose and swore to secrecy.

Both Pithoigia and Choës were considered unlucky and defiled days that necessitated atoning with libations. From this the souls of the dead would come up from the underworld and walked the earth. People chewed on buckthorn leaves and smeared tar on their doors to protect themselves from evil.

- The Third Day

The third day, Chytri (feast of pots), was a festival of the dead. Cooked legumes were offered to Hermes, son of Zeus, and he would make the souls of the deceased depart.

Sources:

“It’s like New Year’s Day for the dead.” That’s how Sherly Turenne sums up the celebration for Ghede spirits, led by Baron Samedi, god of death in Haiti’s Vodun tradition.

He is anticipated with happiness as the protector of children, provider of wise advice and the last best hope for the seriously ill. Celebrated on Nov. 2, along with the Catholic All Souls’ Day, Ghede (GEH-day) is also a day to remember and honor ancestors.

All boons granted by the Ghede must be repaid by this date or they will take their vengeance on you.

About the Ghede:

With a population of 8.5 million, Haiti is 90 percent Catholic and 100 percent Vodun (VOH-doon), a religion that accommodated the practices and principles of captives from Dahomey, Yorubaland, Congo and Angola who were brought to the island during the African slave trade.

The Dahomey/Yoruba term can refer both to the verb gede, to cut through, and igede, incantation, hinting at cutting through to mystery, in this case the mystery of death. Because the Africans combined the elements of their various geographical regions, there came to be in Haiti many Ghedes, several Barons and a creole term referring to a formal god, all referring to the dead and death itself.

Ghedes are part of the pantheon of gods known as Loa (Loh-WAH). Ghede then, as the ruler of death and embodying also the principle of resurrection, governs the preservation and renewal of life. He is sometimes also referred to with affection as Papa Ghede.

The Celebration:

People will put on their Sunday best, and go to church first thing in the morning to pray.

Then they will go home and put on the regalia of the ragtag Ghedes, as the spirits of the underworld are often called, or the elegant Baron Samedi (SAHM-dee) in his black, white and purple color scheme. An outfit can be as simple as a white blouse and skirt and purple neck scarf or can include a black top hat and tails, a baton or cane, a red bandanna or multicolored necklaces.

It is also common to wear makeup – painting half the face white with black around the eyes or even just dusting the face with flour. Once dressed, celebrants go to the town cemetery, where those who have ancestors there will clean the tombs of their loved ones and leave food for them in remembrance.

The spiritual adepts, the women called mambos and the men called houngans (HONE-gahn), joined by drummers and singers, will pray at a cross rising from a tomb, the symbol of Baron Samedi, summoning the spirits. And then the partying begins.

The seeming contradiction may be difficult for Americans to comprehend. The god of death, Baron Samedi nevertheless pokes fun at death and with his raunchy humor and suggestive, lewd dancing makes fun of the human passion that brings life.

A typical altar in honor of Ghede would include cigarettes; clarin, a Haitian white rum spiced with habanero peppers; a small white image of a skull; white, black and purple candles; satin fabric in the same colors; crosses; a miniature coffin; sequined bottles and a chromolithograph of St. Gerard, a saint associated with Baron Samedi. No altar would be complete without the requisite top hat and cane.

Preparing a feast

Oakland dance instructor Portsha Jefferson, whose great-grandmother was Haitian, has been celebrating the holiday for years, both at home and as part of a public gathering. She will prepare a veritable feast for her ancestors, including greens, yams, macaroni and cheese, corn bread, red beans and rice, cabbage, baked chicken and fried snapper, with sweet potato pie for their dessert.

She will begin her day by pouring a libation and offering a prayer in thanks and ask for their blessing. Her altar for Ghede will be refreshed with clarin and set with a vase of fresh flowers and a new white candle. Then she’ll pack up her scandalous Ghede outfit, a black gown with silver and purple sequins that is slit on each side to midthigh, borrow the Baron’s top hat and go to the community celebration, which she has been planning with partner Lee Hetelson.

It was started by the Petit la Croix dance company’s Blanche Brown, who taught Haitian dance in the Bay Area for decades; Jefferson, who took it over in 2003, sends out an e-mail to adepts and dancers asking for volunteers.

“I have people set up on the day-of – decorations, constructing the altar, food preparation, hiring musicians, graphic designers for flyers, administrators for marketing,” she said.

Community celebration

Many community celebrations feature special performances, costume contests, dancing and dance workshops, along with the opportunity to have fun. A Ghede feast is a chance for drummers to play and dancers to dance. It has become really popular, with people wearing Ghede’s clothes.

The party also seems to have a spiritual impact on participants. “I’ve been surprised to hear that people – after dancing- it would lighten up their spirit or help them get through whatever problem they were having at the time.”

In Haiti, preparations had been go on for weeks. At traditional worship sites, called hounfours (HOWN-for), devotees prepare the altar with drapo (flags or cloth) in black, white and purple, lay out Ghede’s attire, and soak habanero peppers in vinegar or water to later be added to clarin for the drink few but the Ghedes can bear to swallow.

The food placed around the altar is very important. It is also important that all the things for other gods are put away. This is to make sure that all of The Baron’s needs are there for when he comes.

Spiritual revellers wear white face paint and drink spicy rum during the two day festival. Devotees can be seen eating glass, carrying dead goats, and drinking from bottles of rum infused with fiery peppers at the spiritual bash.

The Haitians head to a sprawling cemetery in the country’s capital of Port-au-Prince, where voodoo priests and priestesses gather around what is thought to be the nation’s oldest grave.

A man dressed as a “Gede”, or spirit of voodoo, greets people as they enter the cemetery

They then light candles and start small fires to recall the spirit of Baron Samedi the guardian of the dead.

The Day of the Dead festival takes place on November 1 and November 2, when voodoo followers remember relatives who have passed away and asks spirits to grant them favours or offer them advice.

Vendors set up in the cemetery and sell things such as rum, candles and rosary beads.

- 2 cups powdered sugar

- 1 egg white

- 1 TBSP. corn syrup

- 1/2 tsp. vanilla

- 1/3 cup cornstarch

- colored icing

- 1 fine paintbrush

Sift powdered sugar. Mix the egg white, corn syrup, and vanilla in a very clean bowl, then add the powdered sugar with a wooden spoon. When almost incorporated, start kneading with the tip of your fingers until you can form a small ball. Dust with cornstarch on board. Keep on kneading until smooth, then form into skull shapes. Let dry completely, then paint with colored icing, including the names of the people you are giving them to.

In Italy, the sine qua non of All Souls’ celebrations is a cookie called “Ossi di Morto,” or “Bones of the Dead.”

Here’s a recipe:

- 1 1/4 cups flour

- 10 oz almonds

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 1 oz pine nuts

- 1 TBSP butter

- A shot glass full of brandy or grappa

- The grated zest of half a lemon

- Cinnamon

- One egg and one egg white, lightly beaten

Blanch the almonds, peel them, and chop them finely (you can do this in a blender, but be careful not to over-chop and liquefy).

Combine all the ingredients except the egg in a bowl, mixing them with a spoon until you have a firm dough. Dust your hands and work surface with flour, and roll the dough out between your palms to make a “snake” about a half inch thick. Cut it into two-inch long pieces on the diagonal. Put on greased and floured cookie sheet, brush with the beaten egg, and bake them in a 330-350 oven for about 20 minutes. Serve them cold. Because they are a dry, hard cookie, it is good to serve these with something to drink.

As usual with big Catholic Feast days, food is involved with the day, with many Catholic families having picnics near their loved ones’ graves. Traditional foods include “Soul Food” — food made of lentils or peas.

Basic Split Pea Soup (serves 4)

- 1 cup chopped onion

- 2 cloves garlic (optional)

- 1 teaspoon vegetable oil or bacon grease

- 1 pound dried split peas

- 1 pound ham bone

- 1 c. chopped ham

- 1 c. chopped carrots (optional)

- salt and pepper to taste

In a medium pot, sauté onions in oil or bacon grease. (Optional: add garlic and sauté until just golden, then remove). Remove from heat and add split peas, ham bone and ham. Add enough water to cover ingredients, and season with salt and pepper.

Cover, and cook until there are no peas left, just a green liquid, 2 hours. (Optional: add carrots halfway through) While it is cooking, check to see if water has evaporated. You may need to add more water as the soup continues to cook.

Once the soup is a green liquid remove from heat, and let stand so it will thicken. Once thickened you may need to heat through to serve. Serve with either sherry or sour cream on top, and with a crusty bread.

There is a Mexican saying that we die three deaths: the first when our bodies die, the second when our bodies are lowered into the earth out of sight, and the third when our loved ones forget us.

Some believe that the origins of All Souls’ Day in European folklore and folk belief are related to customs of ancestor veneration practiced worldwide. It is practically universal folk belief that the souls of the dead (or those in Purgatory) are allowed to return to earth on All Souls Day. In Austria, they are said to wander the forests, praying for release. In Poland, they are said to visit their parish churches at midnight, where a light can be seen because of their presence. Afterward, they visit their families, and to make them welcome, a door or window is left open. In many places, a place is set for the dead at supper, or food is otherwise left out for them.

In any case, our beloved dead should be remembered, commemorated, and prayed for.

During our visits to their graves, we spruce up their resting sites, sprinkling them with holy water, leaving votive candles, and adorning them flowers (especially chrysanthemums and marigolds) to symbolize the Eden-like paradise that man was created to enjoy, and may, if saved, enjoy after death and any needed purgation.

Today is a good day to not only remember the dead spiritually, but to tell your children about their ancestors. Bring out those old photo albums and family trees! Write down your family’s stories for your children and grandchildren! Impress upon them the importance of their ancestors!

Traditional foods:

Around the world:

The formal commemoration of the saints and martyrs (All Saints’ Day) existed in the early Christian church since its legalization, and alongside that developed a day for commemoration of all the dead (All Souls’ Day). The modern date of All Souls’ Day was first popularized in the early eleventh century after Abbot Odilo established it as a day for the monks of Cluny and associated monasteries to pray for the souls in purgatory.

Many of these European traditions reflect the dogma of purgatory. For example, ringing bells for the dead was believed to comfort them in their cleansing there, while the sharing of soul cakes with the poor helped to buy the dead a bit of respite from the suffering of purgatory. In the same way, lighting candles was meant to kindle a light for the dead souls languishing in the darkness. Out of this grew the traditions of “going souling” and the baking of special types of bread or cakes.

In Tirol, cakes are left for them on the table and the room kept warm for their comfort. In Brittany, people flock to the cemeteries at nightfall to kneel, bareheaded, at the graves of their loved ones, and to anoint the hollow of the tombstone with holy water or to pour libations of milk on it. At bedtime, the supper is left on the table for the souls.

In Bolivia, many people believe that the dead eat the food that is left out for them. In Brazil people attend a Mass or visit the cemetery taking flowers to decorate their relatives’ grave, but no food is involved.

In Malta many people make pilgrimages to graveyards, not just to visit the graves of their dead relatives, but to experience the special day in all its significance. Visits are not restricted to this day alone. During the month of November, Malta’s cemeteries are frequented by families of the departed. Mass is also said throughout the month, with certain Catholic parishes organizing special events at cemetery chapels.

In Linz, funereal musical pieces known as aequales were played from tower tops on All Soul’s Day and the evening before.

In Mexico “Dia de Los Muertos” (Day of the Dead) is celebrated very joyfully — and colorfully. A special altar, called an ofrenda, is made just for these days of the dead (1 and 2 November). It has at least three tiers, and is covered with pictures of Saints, pictures of and personal items belonging to dead loved ones, skulls, pictures of cavorting skeletons (calaveras), marigolds, water, salt, bread, and a candle for each of their dead (plus one extra so no one is left out).

A special bread is baked just for this day, Pan de Muerto, which is sometimes baked with a toy skeleton inside. The one who finds the skeleton will have “good luck.” This bread is eaten during picnics at the graves along with tamales, cookies, and chocolate. They also make brightly-colored skulls out of sugar to place on the family altars and give to children.

Collected from various sources

The pan de muerto (Spanish for Bread of the Dead or Day of the Dead Bread) is a type of bread from Mexico baked during the Dia de los Muertos season, around the end of October and the official holiday is celebrated on November 2. It is a soft bread shaped in round loaves with strips of dough attached on top (to resemble bones), and usually covered or sprinkled with sugar.

Another bread in the form of a sphere on the top represents a skull. The classic recipe for Pan de Muerto is a simple sweet bread recipe with the addition of anise seeds.

Pan de Muerto is sometimes baked with a toy skeleton inside. The one who finds the skeleton will have “good luck.” This bread is eaten during picnics at the graves along with tamales, cookies, and chocolate.

Ingredients:

- 1/4 cup milk

- 1/4 cup (half a stick) margarine or butter, cut into 8 pieces

- 1/4 cup sugar

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1 package active dry yeast

- 1/4 cup very warm water

- 2 eggs

- 3 cups all-purpose flour, unsifted

- 1/2 teaspoon anise seed

- 1/4 teaspoon ground cinnamon

- 2 teaspoons sugar

Instructions: Bring milk to boil and remove from heat. Stir in margarine or butter, 1/4 cup sugar and salt.

In large bowl, mix yeast with warm water until dissolved and let stand 5 minutes. Add the milk mixture.

Separate the yolk and white of one egg. Add the yolk to the yeast mixture, but save the white for later. Now add flour to the yeast and egg. Blend well until dough ball is formed.

Flour a pastry board or work surface very well and place the dough in center. Knead until smooth. Return to large bowl and cover with dish towel. Let rise in warm place for 90 minutes. Meanwhile, grease a baking sheet and preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

Knead dough again on floured surface. Now divide the dough into fourths and set one fourth aside. Roll the remaining 3 pieces into “ropes.”

On greased baking sheet, pinch 3 rope ends together and braid. Finish by pinching ends together on opposite side. Divide the remaining dough in half and form 2 “bones.” Cross and lay them atop braided loaf.

Cover bread with dish towel and let rise for 30 minutes. Meanwhile, in a bowl, mix anise seed, cinnamon and 2 teaspoons sugar together. In another bowl, beat egg white lightly.

When 30 minutes are up, brush top of bread with egg white and sprinkle with sugar mixture, except on cross bones. Bake at 350 degrees for 35 minutes.

Makes 8 to 10 servings.

Recipe found at: AzCentral