New Years Celebrations

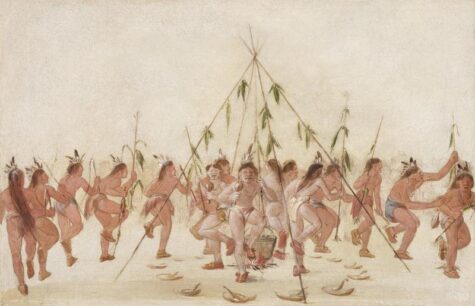

The Green Corn Ceremony typically occurs in late July– early August, determined locally by the ripening of the corn crops. The ceremony is marked with dancing, feasting, fasting and religious observations.

The Green Corn Ceremony is a celebration of many types, representing new beginnings. Also referred to as the Great Peace Ceremony, it is a celebration of thanksgiving to Hsaketumese (The Breath Maker) for the first fruits of the harvest, and a New Year festival as well.

The Feast of Green Corn and Dance gives honor to Mantoo (Creator) provider of all things and celebrates our harvest, ancestors, elders, veterans, family and Native American heritage.

The Green Corn Ceremony is an annual ceremony practiced among various Native American peoples associated with the beginning of the yearly corn harvest.

These ceremonies have been documented ethnographically throughout the North American Eastern Woodlands and Southeastern tribes. Historically, it involved a first fruits rite in which the community would sacrifice the first of the green corn to ensure the rest of the crop would be successful.

These Green Corn festivals were practiced widely throughout southern North America by many tribes evidenced in the Mississippian people and throughout the Mississippian Ideological Interaction Sphere. Green Corn festivals are still held today by many different Southeastern Woodland tribes.

Literally the spirit of the corn in Native American traditions, Corn Mother brings with her the bounty of earth, its healing capabilities, it’s nurturing nature, and its providence.

- Symbols: Corn; Corn Sheaves

- Themes: Abundance; Children; Energy; Fertility; Harvest; Health; Grounding; Providence; Strength

This is the season when Corn Mother really shines, beautiful with the harvest. She is happy to share of this bounty and give all those who seek her an appreciation of self, a healthy dose of practicality, and a measure of good common sense.

To Do Today:

Around this time of year the Seminole Indians (in the Florida area) dance the green corn dance to welcome the crop and ensure ongoing fertility in the fields and tribe. This also marks the beginning of the Seminole year. So, if you enjoy dancing, grab a partner and dance? Or, perhaps do some dance aerobics. As you do, breathe deeply and release your stress into Corn Mother’s keeping. she will turn it into something positive, just as the land takes waste and makes it into beauty.

Using corn in rituals and spells is perfectly fitting for this occasion. Scatter cornmeal around the sacred space to mark your magic circle, or scatter it to the wind so Corn Mother can bring fertility back to you. Keeping a dried ear of corn in the house invokes Corn Mother’s protection and luck, consuming corn internalizes her blessings.

The traditional Ceremony:

The Busk or Green Corn Ceremony is the celebration of the New Year, so at this time all offenses are forgiven except for rape and murder, which are executable or banishable offenses.

In modern tribal towns and Stomp Dance societies only the ceremonial fire, the cook fires and certain other ceremonial objects will be replaced. Everyone usually begins gathering by the weekend prior to the ceremony, working, praying, dancing and fasting off and on until the big day.

The whole festival tends to last seven-eight days, if you include the historical preparation involved (without the preparation, it lasts about four days).

- Day One

The first day of the ceremony, people set up their campsites on one of the square ceremonial grounds. Following this, there is a feast of the remains of last year’s crop, after which all the men of the community begin fasting (historically, the women were considered too weak to participate). That night there is a social stomp dance, unique to the Muscogee and Southeastern cultures.

- Day Two

Before dawn on the second day, four brush-covered arbors are set up on the edges of the ceremonial grounds, one in each of the sacred directions.

For the first dance of the day, the women of the community participate in a Ribbon or Ladies Dance, which involves fastening rattles and shells to their legs perform a purifying dance with special ribbon-clad sticks to prepare the ceremonial ground for the renewal ceremony.

The ceremonial fire is set in the middle of four logs laid crosswise, so as to point to the four directions. The Mico (head priest) takes out a little of each of the new crops (not just corn, but beans, squash, wild plants, and others) rubbed with bear oil, and it is offered together with some meat as “first-fruits” and an atonement for all sins.

The fire (which has been re-lit and nurtured with a special medicine by the Mico) will be kept alive until the following year’s Green Corn Ceremony. In traditional times, the women would sweep out their cook-fires and the rest of their homes and collect the filth from this, as well as any old clothing and furniture to be burnt and replaced with new items for the new year.

The women then bring the coals of the fire into their homes, to rekindle their home fires. They can then bake the new fruits of the year over this fire (also to be eaten with bear oil). Many Creeks also practice the sapi or ceremonial scratches, a type of bloodletting in the mid morning, and in many tribes the men and women might rub corn milk, ash, white clay, or analogous mixtures over themselves and bathe as a form of purification.

They also drink a medicine referred to as the “White Drink.” (English traders referred to it as the “Black Drink” due to its dark liquid which froths white when shaken before drinking).

This White Drink, known to strangers as Carolina Tea, is a caffeine-laden mixture of seven to fourteen different herbs, the main ingredient being assi-luputski, Creek for “small leaves” of Yaupon Holly.

This medicine was intended to help receive purification, as it is a purgative when consumed in mass amounts. (Historically, only men drank enough of the liquid to throw up.) The purgative was consumed to clean the dietary tract of last year’s crop and to truly renew oneself for the new year.

- Day Three

While the second day tends to focus on the women’s dance, the third is focused on the men’s. After the purification of the second day, men of the community perform the Feather Dance to heal the community.

The fasting usually ends by supper-time after the word is given by the women that the food is prepared, at which time the men march in single-file formation down to a body of water, typically a flowing creek or river for a ceremonial dip in the water and private men’s meeting. They then return to the ceremonial square and perform a single Stomp Dance before retiring to their home camps for a feast.

During this time, the participants in the medicine rites are not allowed to sleep, as part of their fast. At midnight a Stomp Dance ceremony is held, which includes feasting and continues on through the night. This ceremony usually ends shortly after dawn.

- Day Four

The fourth day has friendship dances at dawn, games, and people later pack up and return home with their feelings of purification and forgiveness. Fasting from alcohol, sexual activity, and open water will continue for another four days.

More Information

Puskita, commonly referred to as the “Green Corn Ceremony” or “Busk,” is the central and most festive holiday of the traditional Muscogee people. It represents not only the renewal of the annual cycle, but of the spirit and traditions of the Muscogee. This is representative of the return of summer, the ripening of the new corn, and the common Native American traditions of environmental and agricultural renewal.

Historically in the Seminole tribe, 12-year-old boys are declared men at the Green Corn Ceremony, and given new names by the chief as a mark of their maturity.

Several tribes still participate in these ceremonies each year, but tribes who have historic tradition within the ceremony include the Iroquois, Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, and Seminole tribes. Each of these tribes may have their own variations of celebration, dances and traditions, but each performs a new-year’s ceremony involving fasting and several other comparisons each year.

Sources:

July 19 was a very important date in ancient Egyptian Cosmology. Known as ‘The Opening of the Year,” or the “Sothic New Year,” it was celebrated with a festival known as “The Coming of Sopdet.”

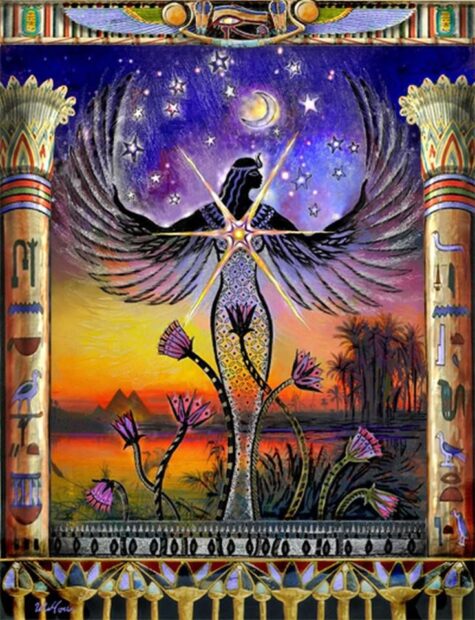

The oldest festival in ancient Egyptian history, the celebration of The Opening of the New Year began with the rising of Sirius who appeared as the goddess Isis cloaked in robes of brilliant light.

The sky is serene. Sothis lives. She shines, a peaceful flame.

Unas lives eternal as the son of Sothis,

As the child of Isis, as a child of Light,

As Earth is child of the Cosmos.

Unas is pure. She is pure,

As are all the gods whoever lived since the beginning of time

In the worlds above and in the worlds below.

They have been born the Imperishable Stars

Living within the Meshetiu, which shall never die.

~Pyramid Text Utterance 302

Sirius forms a part of the constellation Canis Major, sometimes referred to as the Dog Star. Of all the stars in the sky throughout the year, Sirius shines the brightest. The Greeks called the star Sothis, meaning “The Soul of Isis”. The Egyptians called her Sept or Sopdet, referring to the concept of preparing for the future. The ancient feast day name Per Sopdet may be translated as T”he Coming Forth of the Goddess.”

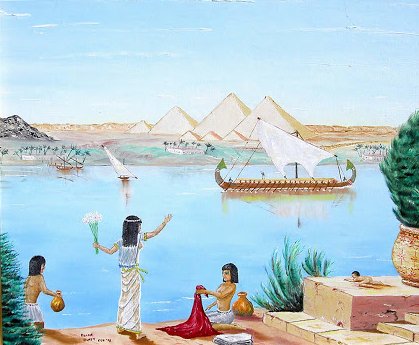

On this day Sirius, the “Dog Star”, rose together with Sun and announced the annual flooding of Nile River. The lands were watered and a black layer of slime covered them, providing humidity and fertilizer for next year’s harvest: the nation would not suffer of hunger. Thus it was the first year of the mystical Egyptian year, symbolizing transmutation and fertility.

Note: The actual date of this event in ancient Egypt is different than the current date because the date slowly varies within the Gregorian calendar, owing to its omission of three leap years every four centuries. It presently occurs on 3 August.

Ancient Egyptian Rites and Festivities

When Sirius reappeared as the morning star, the altars at the Isis temples of Philae, Karnak, and Dendera opened early. The portals and sanctuaries were aligned so precisely with the heavenly bodies that the predawn starlight of Sirius was projected onto the cult statue of the goddess. Thus began a season of preparation for the coming agricultural year and a celebration of the flood and fecundity of earth.

New Year’s Day in every temple across the land began with the lighting of the wicks for the temple fires. The glowing lamplight symbolized the eternal life of the spirit world and the flame’s earthly burning became a mirrored image of the glittering light of Sothis in the sky.

The lifting of the fires was usually followed by an offering of bread and prayers glorifying the dead, enacted in the northern corner of the temple – the northern region being linked with the souls of the ancestors, the Imperishable Ones who were the circumpolar stars.

When the Opening of the year or Wept Renpet was celebrated, it was also a day to celebrate the traditional birthday of the king and later the Pharoah – no matter the true date of his birth. The New Year’s Feast was an important festival in the life of the Egyptian ruler. It involved his ritually hoeing the ground and breaking the dirt clods in preparation for the sowing that would follow the receding waters.

The water stands and fails not, and the Nile carries a high flood. The days are long, the nights have hours, and the months come aright. The Gods are content and happy of heart, and life is spent in laughter and wonder.

~Prayer from the Sallier Papyrus

The galleries inside the pyramids point to the heavenly position of Sirius on such a day. Sirius was both the most important star of ancient Egyptian astronomy, and one of the Decans. Decans are star groups into which the night sky was divided, with each group appearing for ten days annually. The first night that Sirius is seen, just before dawn (heliacal rising) was noticed every year during July, and the Egyptians used this to mark the start of the New Year.

In fact, the “Sothic Rising” only coincided with the solar year once every 1460 years. The Roman emperor Antoninus Pius had a commemorative coin made to mark their coincidence in AD 139. The Sothic Cycle (the periods between the rising of the star) have been used by archaeologists trying to construct a chronology of Ancient Egypt.

About Sopdet

Sirius was named Sothis by Egyptians and from archaic ages it symbolized eternity and fertility. As early as the 1st Dynasty, she was known as ‘the bringer of the new year and the Nile flood. Sopdet took on the aspects of a goddess of not only the star and of the inundation, but of the fertility that came to the land of Egypt with the flood. The flood and the rising of Sirius also marked the ancient Egyptian New Year, and so she also was thought of as a goddess of the New Year.

- Themes: Fertility, Destiny, Time

- Symbols: Stars and Dogs.

Not just a goddess of the waters of the inundation, Sopdet had another link with water – she was believed to cleanse the pharaoh in the afterlife. It is interesting to note that the embalming of the dead took seventy days – the same amount of time that Sirius was not seen in the sky, before it’s yearly rising. She was a goddess of fertility to both the living and the dead.

In the Pyramid Texts, she is the goddess who prepares yearly sustenance for the pharaoh, ‘in this her name of “Year”‘. She is also thought to be a guide in the afterlife for the pharaoh, letting him fly into the sky to join the gods, showing him ‘goodly roads’ in the Field of Reeds and helping him become one of the imperishable stars. She was thought to be living on the horizon, encircled by the Duat.

The reigning Egyptian Queen of the Constellations, Sopdet lives in Sirius, guiding the heavens and thereby human destiny. Sopdet is the foundation around which the Egyptian calendar system revolved, Her star’s appearance heralding the beginning of the fertile season. Some scholars believe that the Star card of the Tarot is fashioned after this Goddess and Her attributes.

The long, hot days of summer are known as the ‘Dog Days‘ because they coincide with the rising of the dog star, Sirius. In ancient Egypt this was a welcome time as the Nile rose, bringing enriching water to the land.

Activities for Today

Go outside tonight and see if you can find Sirius. When you spy it, whisper a wish to Sopdet suited to Her attributes and your needs. For example, if you need to be more timely or meet a deadline, she’s the perfect Goddess to keep things on track.

If you’re curious about your destiny, watch that region of the sky and see if any shooting stars appear. If so, this is a message from Sopdet. A star moving on your right side is a positive omen; better days are ahead. Those on the left indicate the need for caution, and those straight ahead mean things will continue on an even keel for now. Nonetheless, seeing any shooting star means Sopdet has received your wish.”

- Recall a new beginning

Recall a time in your life when you were starting anew, perhaps after a divorce or when moving into a new home. Perhaps your new life followed the birth of a child or a change in career. Investigate what had to die in your old life in order for the new life to emerge. How did that feel as you stood poised on the brink of change?

- Explore your creativity

Explore what it means to be creative. Think about the most creative times in your life. Where did you live? How different did life seem then from the way it seems now? How was your time structured? What were you thinking, desiring, telling yourself on a daily basis? Can you duplicate any of that in your life now?

- Ten Things

Make a list right now of ten things you want to manifest in the next six months. Be specific. Plant three seeds for each thing you want to manifest, then tend to them. Mark each seed with a popsicle stick to indicate what goal you are germinating, so that when you water the plant, you stay focused on what you are nurturing within yourself.

Write a brief prayer to one of the abundance goddesses – Isis, Hathor, or Anket – asking her to guide you and oversee your fecundity. Say your prayer each time you tend your plants.

Sources:

- Tour Egypt

- Journeying To The Goddess

- Feasts of Light

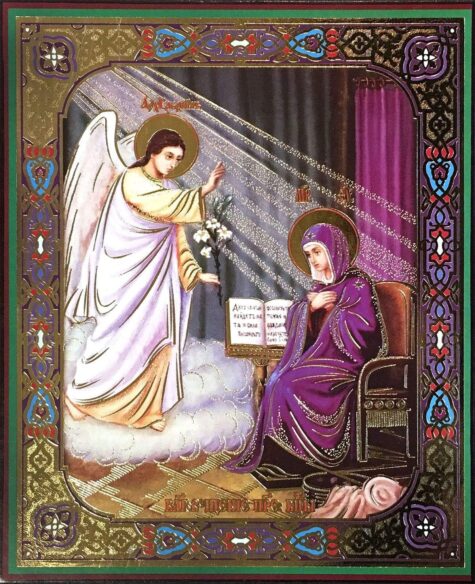

The precession of the equinoxes has moved the astronomical beginning of spring back four days to March 21, but its previous date of March 25 became identified with the Virgin Mary, who was told by the angel Gabriel on that day that she would become the mother of Christ.

Lady Day, as this day was commonly called, was one of the great quarterly dividing points of the year (the others being Midsummer Day, Michaelmas, and Christmas). It was traditionally the day for paying rents, signing or vacating leases, and hiring farm laborers for the year.

The flower cardamine, or lady’s-smock, with its milky white flowers, is dedicated to the Virgin Mary and appears about this time.

The Christian New Year’s Day

For centuries the Solemnity of the Annunciation on March 25, not Jan. 1, marked the first day of the New Year.

“Happy New Year!” is what we would have celebrated along with the Feast of the Annunciation on March 25 if we were living some centuries ago. Back then, the Annunciation also marked the start of the New Year.

The choice was well thought out and gives us lots to contemplate. Let’s begin at this point: when reforming the calendar in 45 B.C., Julius Caesar made Jan. 1 New Year’s Day. Celebrated with non-Christian festivities, of course.

Naturally, after Jesus life, death and resurrection, the Christians wanted to celebrate New Year’s Day in a spiritual way.

One early thought was to begin the year in springtime, a natural “new beginning.” And around the time of his Resurrection. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, what also came into play was the Jewish month of Nisan, which coincides with March and April on the Julian and Gregorian calendars and opens the sacred year.

But then arose the question, on which day should the New Year begin for Christians?

That answer really narrowed down when in the sixth century there came along the monk and abbot named Dionysius Exiguus, who lived in Rome. His name isn’t familiar today, but his work certainly is, especially in the use of B.C. and A.D. He established this way of dating from the birth of Jesus Christ — Before Christ and Anno Domini (the Year of Our Lord). Dionysius wanted to start the Christian era in order to reform the Roman calendar and way of calculating events. One of his great concerns was coming up with the date of Easter.

Naturally, the first day of the New Year had to fit somewhere in the new calendar. But where?

“Since March 25 was calculated as the date of the crucifixion of Jesus, there was a belief that one died on the same day that one was conceived,” writes Father John Fields, vice chancellor and director of communications for the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia. “If Jesus died on March 25 — the 14th of Nisan — then he was also conceived on the 14th of Nisan — March 25.” The date we celebrate the Annunciation. And the Incarnation.

But everyone didn’t adopt it immediately because the Julian calendar was still in widespread use. Besides, here and there in Europe, at times Dec. 25, the Nativity, was being celebrated as New Year’s.

Then along came the Council of Tours which in A.D. 567, put an end to Jan. 1 as New Year’s Day and adopted March 25 as the official first day of the New Year. Soon, yet slowly, countries in Europe were using that date to begin the official New Year. By the 8th century England had adopted this way of reckoning the year. The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that Charlemagne is believed to be the first Christian sovereign to use it.

Father Fields and other sources also point out that March 25 also had other implications. There was a general belief coming from early martyrologies and the early Church Fathers’ writings that March 25 was also the date on which Adam was created and which marked his fall, as well as other major events — the fall of Lucifer; Moses and the Israelites flight through the Red Sea; and Isaac offered in sacrifice by Abraham.

In 1582, along came Pope Gregory XIII who reformed the calendar. Doing so, for the calendar we now use, he placed New Year’s Day, the first day of the year, back to January 1. As he reformed the liturgical calendar also this became the Feast of the Circumcision.

But the Protestant countries weren’t so fast accepting the new Gregorian calendar. The British Empire continued to celebrate New Year’s Day on March 25 until finally adopting the Gregorian calendar on January 1, 1752.

“Until 1751, March 25 was also celebrated as New Year’s Day in the American colonies, since they were under British rule,” adds Father Fields.

Is March 25 still celebrated anywhere as New Year’s Day?

It sure is. In Tuscany in Italy. This year marks the 270th anniversary of the city of Pisa celebrating New Year’s Day on March 25. Florence does likewise (both celebrate the “other” New Year too). The event, begun in 1749, is quite colorful with concerts and festivals. Pisa has a procession to Pisa Cathedral which is dedicated to the Blessed Mother, while in Florence a local pilgrimage proceeds to the Basilica dell’Annunciazione.

So this March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation, remember that for centuries this feast day was the Christian New Year’s Day.

On March 25, instead of thinking of a weepy Auld Lang Syne sort of song, pray or recite with the greatest of joy the Magnificat. For through the Annunciation and Mary’s Fiat, Our Lord Jesus was incarnated and then crucified for our redemption. Now that’s something to really wish someone a Happy New Year about!

God Becomes A Man

The central focus of the Annunciation is Incarnation: God has become one of us. From all eternity God had decided that the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity should become human.

Now the decision is being realized. The God-Man embraces all humanity, indeed all creation, to bring it to God in one great act of love. Because human beings have rejected God, Jesus will accept a life of suffering and an agonizing death.

Mary has an important role to play in God’s plan. From all eternity, God destined her to be the mother of Jesus and closely related to him in the creation and redemption of the world. We could say that God’s decrees of creation and redemption are joined in the decree of Incarnation.

Because Mary is God’s instrument in the Incarnation, she has a role to play with Jesus in creation and redemption. It is a God-given role. It is God’s grace from beginning to end. Mary becomes the eminent figure she is only by God’s grace. She is the empty space where God could act. Everything she is she owes to the Trinity.

Together with Jesus, Mary is the link between heaven and earth. She is the human being who best, after Jesus, exemplifies the possibilities of human existence. She received into her lowliness the infinite love of God. She shows how an ordinary human being can reflect God in the ordinary circumstances of life. She exemplifies what the Church and every member of the Church is meant to become. She is the ultimate product of the creative and redemptive power of God. She manifests what the Incarnation is meant to accomplish for all of us.

Sometimes spiritual writers are accused of putting Mary on a pedestal and thereby, discouraging ordinary humans from imitating her. Perhaps such an observation is misguided. God did put Mary on a pedestal and has put all human beings on a pedestal. We have scarcely begun to realize the magnificence of divine grace, the wonder of God’s freely given love. The marvel of Mary—even in the midst of her very ordinary life—is God’s shout to us to wake up to the marvelous creatures that we all are by divine design.

Sources:

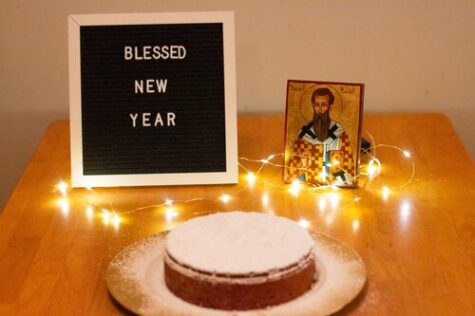

St. Basil’s Day, January 1st, commemorates the day in which (it’s believed) Basil of Caesarea died. The Festival of Saint Basil is the Greek New Year.

In Greek tradition, Basil brings gifts to children every January 1. Children leave their shoes by the fireplace in hopes that St. Basil will fill them with gifts. A large feast is prepared, the larger the luckier the year will be. Pork is usually the main dish. It is customary on his feast day to visit the homes of friends and relatives, to sing New Year’s carols, and to set an extra place at the table for Saint Basil.

Traditionally Vasilopita or Vaselopita, a special bread or cake, is baked on St. Basil’s Day Eve, and served at midnight. The cake is handed out in a particular order. The first piece is for the remembrance of St. Basil and the second is for the household. Those pieces are taken to the church to be blessed, then given to the poor. The rest of the slices are distributed from the eldest member of the household to the youngest.

A coin or trinket is hidden inside the cake, and the person who gets the piece with the hidden treasure will have luck in the coming year.

Vasilopita | St. Basil’s Bread

Make sure everyone knows a quarter is hidden in the cake so they search for it and do not choke on it.

- 1 cup butter, unsalted

- 2 cups granulated sugar

- 3 cups all-purpose flour

- 1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

- 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg

- 6 eggs

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 cup warm milk

- 1 tablespoon lemon juice

- zest of 1 orange

- zest of 1 lemon

- 1/4 cup blanched slivered almonds

- 2 tablespoons granulated sugar

- a clean quarter

Preheat oven to 350F. Generously grease a 10-inch round cake pan. Cream the butter and sugar together until light and fluffy. Stir in the flour, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Mix until mealy. Add the eggs one at a time, mixing well after each addition.

In a separate bowl, combine baking powder, baking soda, milk, lemon juice, and zests. Mix into the batter, then pour into prepared pan. Sprinkle with nuts and sugar. Bake 40-45 minutes. Gently push a quarter into the cake. Cool 10 minutes. Invert cake onto platter. Serve warm.

A Feast Day Prayer to Saint Basil

Saint Basil, O great follower of God, help all as well as me. Defender of orthodoxy, defend us too. Great follower of God, pray to him for all your people, as well as for unworthy me. Strong knight and leader of Ostrog, save us from the seen and unseen. Raised by Serbian soil to be the light in front of God, be our light and light up our road, and make the darkness disappear.

With prayer and tears you have warmed the cold cliffs of Ostrog, please warm our hearts with God’s spirit, so we can be saved. From all corners of the world to your grave come the weak and the ill, and you helped them, got rid of their demons as well as the devil, and healed their souls and bodies.

Please continue to help, the baptized and the nonbaptized, everybody and me as well. You brought peace to fighting brothers, please continue to bring peace, help the divided, make the sad happy, calm the stubborn, heal the sick. Saint Basil, O miracle worker, father of our spirit, listen and hear your children’s spirits in the name of Jesus Christ.

Amen.

About Saint Basil

Basil, being born into a wealthy family, gave away all his possessions to the poor, the underprivileged, those in need, and children. For Greeks and others in the Orthodox tradition, Basil is the saint associated with Santa Claus as opposed to the western tradition of St Nicholas

St. Basil, also called Saint Basil the Great, is one of the most distinguished Doctors of the Church and a forefather of the Greek Orthodox Church. St. Basil was born in the year 329 or 330 and died in the year 379. He is the Patron of Russia, Cappadocia, hospital administrators, reformers, monks, education, exorcism, and liturgists.

Basil’s life changed radically after he encountered Eustathius of Sebaste, a charismatic bishop and ascetic. Abandoning his legal and teaching career, Basil devoted his life to God. In a letter he described his spiritual awakening:

I had wasted much time on follies and spent nearly all of my youth in vain labors, and devotion to the teachings of a wisdom that God had made foolish. Suddenly, I awoke as out of a deep sleep. I beheld the wonderful light of the Gospel truth, and I recognized the nothingness of the wisdom of the princes of this world.

Hot-blooded and somewhat imperious, Basil was also generous and sympathetic. He personally organized a soup kitchen and distributed food to the poor during a famine following a drought. He gave away his personal family inheritance to benefit the poor of his diocese.

His letters show that he actively worked to reform thieves and prostitutes. They also show him encouraging his clergy not to be tempted by wealth or the comparatively easy life of a priest, and that he personally took care in selecting worthy candidates for holy orders. He also had the courage to criticize public officials who failed in their duty of administering justice. At the same time, he preached every morning and evening in his own church to large congregations.

In addition to all the above, he built a large complex just outside Caesarea, called the Basiliad, which included a poorhouse, hospice, and hospital, and was compared by Gregory of Nazianzus to the wonders of the world.

His three hundred letters reveal a rich and observant nature, which, despite the troubles of ill-health and ecclesiastical unrest, remained optimistic, tender and even playful. His principal efforts as a reformer were directed towards the improvement of the liturgy, and the reformation of the monastic institutions of the East.

There are numerous relics of Basil throughout the world. One of the most important is his head, which is preserved to this day at the monastery of the Great Lavra on Mount Athos in Greece. The mythical sword Durandal is said to contain some of Basil’s blood.

Some Great St Basil Quotes

I really love some of these quotes. They are surprisingly applicable to modern life. Enjoy!

Alternative St Basil Feast Days

According to some sources, Basil died on January 1, and the Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates his feast day together with that of the Feast of the Circumcision on that day. This was also the day on which the General Roman Calendar celebrated it at first; but in the 13th-century it was moved to June 14, a date believed to be that of his ordination as bishop, and it remained on that date until the 1969 revision of the calendar, which moved it to January 2 (rather than January 1) because the latter date is occupied by the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God.

On January 2 Saint Basil is celebrated together with Saint Gregory Nazianzen. Some traditionalist Catholics continue to observe pre-1970 calendars.

The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod commemorates Basil, along with Gregory of Nazianzus and Gregory of Nyssa on January 10.

The Church of England celebrates Saint Basil’s feast on January 2, but the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Church of Canada celebrate it on June 14.

In the Byzantine Rite, January 30 is the Synaxis of the Three Holy Hierarchs, in honor of Saint Basil, Saint Gregory the Theologian and Saint John Chrysostom.

The Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria celebrates the feast day of Saint Basil on the 6th of Tobi (6th of Terr on the Ethiopian calendar of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church). At present, this corresponds to January 14, January 15 during leap year.

Sources:

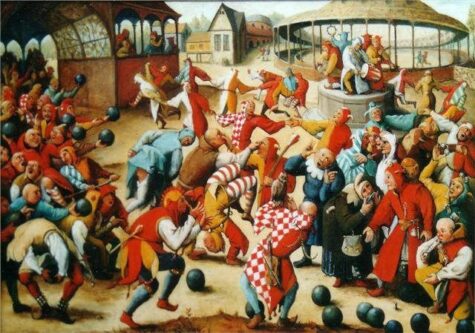

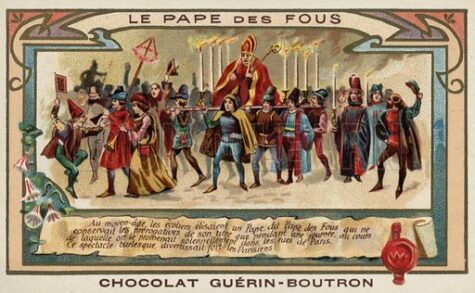

Feast of Fools was a celebration marked by wanton mischief and merrymaking. It took place in many parts of Europe, and particularly in France, every year during the later middle ages on or about the Feast of the Circumcision (1 Jan.). This feast day, as described by the French theologians who condemned it in 1445, sounds like a ton of fun.

This New Year’s Day celebration, they wrote, caught up high-ranking church officials in a bacchanal unworthy of their exalted positions.

“Priests and clerks may be seen wearing masks and monstrous visages at the hours of office,” the theologians recounted, presumably with a sniff of horror. “They dance in the choir dressed as women, panders or minstrels. They sing wanton songs. They eat black puddings… while the celebrant is saying mass. They play at dice… They run and leap through the church, without a blush at their own shame.”

The Feast of Fools was celebrated by the clergy in Europe during the Middle Ages, initially in Northern France, but later more widely. During the Feast, participants would elect either a false Bishop, false Archbishop or false Pope. Ecclesiastical ritual would also be parodied and higher and lower level clergy would change places.

It was known by many names:

- Festum

- Fatuorum

- Festum stultorum

- Festum hypodiaconorum

Officially banned in the 15th century, the Feast of Fools had its origins 300 years before, in the 1100s, and continued as a tradition well into the 16th century. It was memorialized in church documents condemning its excesses and in paintings depicting streets full of merry chaos. It appears in Victor Hugo’s famous 19th century novel, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, when Quasimodo is swept up in the festivities and crowned King of Fools.

This rowdy revelry may never has been quite as raucous as was rumored. It started out as a much tamer liturgical celebration, which accrued an outsized reputation for subversiveness. At its heart, though, the Feast of Fools always turned power on its head—a reversal that naturally made church leaders very nervous.

But outside the church doors, concurrent celebrations were much more irreverent. In these medieval centuries, Harris writes, it became popular for students to parade through the streets with their faces blackened with mud (or even animal dung) to conceal their identities while they parodied clergy, doctors, civil officials, and rulers. These parades certainly featured cross-dressing, drinking, singing, and all manner of other mischief and behavior that usually wouldn’t be tolerated.

Wintertime celebrations like these, where the less powerful parts of society had the chance to break loose for a day, trace their roots to Roman and other European pagan festivals of role-reversal. For a modern day take on this holiday, visit this Feast Of Fools post.

It is difficult to distinguish it from certain other similar celebrations, such as the Feast of Asses, and the Feast of the Boy Bishop. It seems to have grown out of a special “festival of the subdeacons”, which John Beleth, a liturgical writer of the twelfth century and an Englishman by birth, assigns to the day of the Circumcision.

He was among the earliest to draw attention to the fact that, as the deacons had a special celebration on St. Stephen’s day (26 Dec.), the priests on St. John the Evangelist’s day (27. Dec.), and again the choristers and mass-servers on that of Holy Innocents (28 Dec.), so the subdeacons were accustomed to hold their feast about the same time of year, but more particularly on the festival of the Circumcision.

This feast of the subdeacons afterwards developed into the feast of the lower clergy (esclaffardi), and was later taken up by certain brotherhoods or guilds of “fools” with a definite organization of their own. There can be little doubt — and medieval censors themselves freely recognized the fact — that the license and buffoonery which marked this occasion had their origin in pagan customs of very ancient date.

John Beleth, when he discusses these matters, entitles his chapter “De quadam libertate Decembrica“, and goes on to explain: “now the license which is then permitted is called Decembrian, because it was customary of old among the pagans that during this month slaves and serving-maids should have a sort of liberty given them, and should be put upon an equality with their masters, in celebrating a common festivity.” (P.L. CCII, 123).

The Feast of Fools and the almost blasphemous extravagances in some instances associated with it have constantly been made the occasion of a sweeping condemnation of the medieval Church.

There can be no question that ecclesiastical authority repeatedly condemned the license of the Feast of Fools in the strongest terms, no one being more determined in his efforts to suppress it than the great Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln. But these customs were so firmly rooted that centuries passed away before they were entirely eradicated.

In defense of the medieval Church one point must not be lost sight of. We possess hundreds, not to say thousands, of liturgical manuscripts of all countries and all descriptions. Amongst them the occurrence of anything which has to do with the Feast of Fools is extraordinarily rare. In missals and breviaries we may say that it never occurs.

In 1199, Bishop Eudes de Sully imposed regulations to check the abuses committed in the celebration of the Feast of Fools on New Year’s Day at Notre-Dame in Paris. The celebration was not entirely banned, but the part of the “Lord of Misrule” or “Precentor Stultorum” was restrained within decorous limits.

The central idea seems always to have been that of the old Saturnalia, i.e. a brief social revolution, in which power, dignity or impunity is conferred for a few hours upon those ordinarily in a subordinate position. Whether it took the form of the boy bishop or the subdeacon conducting the cathedral office, the parody must always have trembled on the brink of burlesque, if not of the profane.

We can trace the same idea at St. Gall in the tenth century, where a student, on the thirteenth of December each year, enacted the part of the abbot. It will be sufficient here to notice that the continuance of the celebration of the Feast of Fools was finally forbidden under the very severest penalties by the Council of Basle in 1435, and that this condemnation was supported by a strongly-worded document issued by the theological faculty of the University of Paris in 1444, as well as by numerous decrees of various provincial councils. In this way it seems that the abuse had practically disappeared before the time of the Council of Trent.

Sources:

Nyepi Day in Bali is a New Year celebration unlike anywhere else on the planet. Unlike other cultures that celebrate New Year with vivacious and loud festivities, the pinnacle of Balinese New Year is a day of complete Silence. Hence the name Nyepi, meaning “to keep silent” in the local language, which falls on the day following the dark moon of the spring equinox.

It’s ultimately the quietest day of the year, when all of the island’s inhabitants abide by a set of local rules. These bring all routine activities to a complete halt. Roads all over Bali are void of any traffic and nobody steps outside of their home premises.

Nyepi is a day fully dedicated to connect oneself more closely with God (Hyang Widi Wasa) through prayers and at the same time as a day of self-introspection to decide on values, such as humanity, love, patience, kindness, and others, that should be kept forever.

The unique day of silence marks the turn of the Saka calendar of western Indian origin. It’s one among the many calendars assimilated by Indonesia’s diverse cultures. The Saka is also among two calendars that are jointly used in Bali. The Saka is 78 years behind the Gregorian calendar, and follows a lunar sequence. Nyepi follows after a new moon, and the dates vary from year to year.

Before the Silence Before ‘the silence’, highlight rituals essentially start three days prior to Nyepi, with colourful processions known as the Melasti pilgrimages. Pilgrims from various village temples all over Bali convey heirlooms on long walks towards the coastlines where elaborate purification ceremonies take place. It is one of the best times to capture on camera the iconic Balinese processions in motion, as parasols, banners and small effigies offer a cultural spectacle.

Village meeting halls known as ‘banjar’ and streets feature papier-mâché effigies called ogoh-ogoh. They are built throughout the weeks leading up to the Saka New Year. Youth groups design and build their mythical figures with intricately shaped and tied bamboo framework before many layers of artwork. These artistic creations are offshoots of the celebration. Much of it has stayed on to become an inseparable element in the island-wide celebration that’s Nyepi Eve.

Then on Saka New Year’s Eve, it is all blaring noise and merriment. Every Balinese household starts the evening with blessings at the family temple and continues with a ritual called the pengrupukan where each member participates in ‘chasing away’ malevolent forces, known as bhuta kala, from their compounds – hitting pots and pans or any other loud instruments along with a fiery bamboo torch. These ‘spirits’ are later manifested as the ogoh-ogoh to be paraded in the streets. As the street parades ensue, bamboo cannons and occasional firecrackers fill the air with flames and smoke. The Nyepi Eve parade usually starts at around 19:00 local time.

However on Nyepi Day, complete calm enshrouds the island. The Balinese Hindus follow a ritual called the Catur Brata Penyepian, roughly the ‘Four Nyepi Prohibitions’. These include:

- amati geni or ‘no fire’

- amati lelungan or ‘no travel’

- amati karya ‘no activity’

- amati lelanguan ‘no entertainment’

Some consider it a time for total relaxation and contemplation, for others, a chance for Mother Nature to ‘reboot’ herself after a year of human pestering. No lights are turned on at night – total darkness and seclusion goes along with this new moon island-wide, from 06:00 to 06:00. No motor vehicles whatsoever are allowed on the streets, except ambulances and police patrols and emergencies. Traditional community watch patrols or pecalang enforce the rules of Nyepi, patrolling the streets by day and night in shifts.

Sources:

This festival marks the start of Spring in the old Roman calendar. Each year the Feriae Marti was held, beginning on the Kalends of March and continuing until the 24th. Dancing priests, called the Salii, performed elaborate rituals over and over again, and a sacred fast took place for the last nine days. The dance of the Salii was complex, and involved a lot of jumping, spinning and chanting. On March 25, the celebration of Mars ended and the fast was broken at the celebration of the Hilaria, in which all the priests partook in an elaborate feast.

March is the third month of the year in the Gregorian calendar system, but was actually the first month on the Roman calendar. Originally named Martius, this month in Ancient Rome was characterized by religious festivals and preparations for war. Mars, the Roman god of war was responsible for protecting Rome and securing victory in military campaigns. He is not to be confused with Ares, the impulsive Greek god of war; Mars was depicted as a more “level-headed” and “virtuous” deity than his Grecian counterpart.

General frivolity was characterized by large processions, animal sacrifices, athletic competitions, and musical performances. Courts were closed, and some agricultural chores were suspended to honor the deities. Merry-making with seeds wasn’t restricted though. Some accounts say Romans tossed seeds in the air during the festival to honor the pending thrust of spring.

During the months of March and October, specially-trained religious leaders, called flamen Martialis, led several Mars-centered festivals including:

- Feriae Marti (celebrating the new year)

- Equirria (the blessing of war horses)

- Tubilistrum (to cleanse and favor trumpets)

One of the most important rituals performed during this time was the rousing of Mars before battle. This critical ritual was performed by the commander of the Roman army who “shook the sacred spears,” shouting, “Mars, vigilia!.”

Because early Roman writers associated Mars with not only warrior prowess, but virility and power, he is often tied to the planting season and agricultural bounty.

Ritual For The Feriae Marti – Festival of Mars

- Color: Red

- Element: Fire

Altar: Set out a red cloth and lay crossed weapons, such as spears and swords, upon it. Lay a helm in the center, a horn, and a burning red candle or torch.

Offerings: Candles. Finger-shaped cakes (strues). Acts of courage, especially those which force one to fight for the defense of another or of one’s beliefs. In the morning, the exercise of Gymnastika shall be hard aerobic movements.

Daily Meal: Finger-cakes. Spicy foods, such as cayenne and chilies. Meat from uncastrated male animals.

Invocation to Mars:

Mars, warrior god, Fire that leaps

And dances, Protector of cities

And of this house, and our spirits,

Courageous one, mirror us back

Some of your courage.

Fearless one, show us a path

Through our many fears.

Armored one, give us protection

From all who would harm us.

And may your sword turn away

All danger from our flesh,

Our bones, our house, our home,

Our hearth and our hearts

Our eyes and our spirits.

Protect us from destruction and ruin,

O fiery god of the shining spear.

We hail you, eternal warrior,

And ask that you grant us

Some small measure

Of your boundless fiery heart.

Chant: (To be accompanied by drums and people clashing blades against shields in the manner of the Salii of ancient times)

Gloria Martial! Gloria Martial! Gloria Martial!

Honoria et Gloria Honoria et Gloria!

A libation of red wine is poured out for Mars. One person lifts the horn and winds it, long and slow, five times, and the rite is ended.

Sources:

According to historical documents, on the day when Shun, who was one of ancient China’s mythological emperors, came to the throne more than 4000 years ago, he led his ministers to worship heaven and earth. From then on, that day was regarded as the first day of the first lunar month in the Chinese calendar. This is the basic origin of Chinese New Year.

The new year is by far the most important festival of the Chinese lunar calendar. A long time ago, the emperor determined the start of the New Year. Today, celebrations are based on Emperor Han Wu Di’s almanac. It uses the first day of the first month of the Lunar Year as the start of Chinese New Year. The Chinese New Year always occurs in January or February on the second new moon after the winter solstice, though on occasion it has been the third new moon.

In 2019, the Chinese New Year officially begins on February 5th and ends on February 19th. This begins the Year of the Pig.

The holiday is a time of renewal, with debts cleared, new clothes bought, shops and homes decorated, and families gathered for a reunion dinner. Enjoying extravagant foods with family and friends is arguably the cornerstone of the occasion, along with receiving the ubiquitous red envelopes full of cash (called lai see in Cantonese, or hongbao in Mandarin).

Chinese New Year is marked by fireworks, traditional lion dances, gift giving, and special foods. This is one of the most important holidays. It is observed all over the world. Similar celebrations occur in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam known as the Lunar New Year or the Spring Festival. The “Spring Festival” in modern Mainland China, is China’s most important traditional festival, this public holiday starts on the Chinese New Year, and lasts for 7 days.

About The Chinese Calendar

The Chinese Calendar is a based on the cycles of the moon. The start of the New Year begins anywhere from late January to mid-February. A complete lunar cycle takes 60 years. It is composed of five cycles that are 12 years each. Each 12-year segment is named after an animal.

According to legend, Buddha called all the animals to him before he departed from earth. Only twelve came and as a reward to them, he named the years after them in the order they arrive (the order is listed below). It is believed the animal ruling of the year you are born effects your personality and “it is the animal that hides in your heart”.

The Chinese calendar uses the stem-branch system. The branches are the 12 years. There are ten stems that are used in the counting system. The stems are metal, water, wood, fire and soil; each having a yin and a yang side. There are a lot more intricacies in the system, but you should also know that the elements correlate to colors. Metal=white or golden, water=black, wood=green, fire=red, and soil=brown.

When you put all of this together you end up with the following:

- 2007 is the Year of the Red Pig

- 2008 is the Year of the Brown Rat

- 2009 is the Year of the Brown Ox

- 2010 is the Year of the White or Golden Tiger

- 2011 is the Year of the White or Golden Rabbit

- 2012 is the Year of the Black Dragon

- 2013 is the Year of the Black Snake

- 2014 is the Year of the Green Horse

- 2015 is the Year of the Green Sheep

- 2016 is the Year of the Red Monkey

- 2017 is the Year of the Red Rooster

- 2018 is the Year of the Brown Dog

- 2019 is the Year of the Brown Pig

- 2020 is the Year of the White Rat

Which Chinese zodiac animal are you?

According to the Asian astrology, your year of birth – and the animal this represents – determines a lot about your personality traits. Find the year you were born, and you can figure out which animal in the Chinese Zodiac is yours. The animal changes at the beginning of the Chinese New Year, and traditionally these animals were used to date the years.

Remember, Chinese New Year is a movable celebration, dictated by the lunar cycle, which can fall anytime between January 21 and February 20. So, if you were born during that time, you may need to do some research to figure out which animal applies to you.

- Rat: 2008, 1996, 1984, 1972, 1960, 1948

- Ox: 2009, 1997, 1985, 1973, 1961, 1949

- Tiger: 2010, 1998, 1986, 1974, 1962, 1950

- Rabbit: 2011, 1999, 1987, 1975, 1963, 1951

- Dragon: 2012, 2000, 1988, 1976, 1964, 1952

- Snake: 2013, 2001, 1989, 1977, 1965, 1953

- Horse: 2014, 2002, 1990, 1978, 1966, 1954

- Goat: 2015, 2003, 1991, 1979, 1967, 1955

- Monkey: 2016, 2004, 1992, 1980, 1968, 1956

- Rooster: 2017, 2005, 1993, 1981, 1969, 1957

- Dog: 2018, 2006, 1994, 1982, 1970, 1958

- Pig: 2019, 2007, 1995, 1983, 1971, 1959

Traditions

Traditions observed during the New Year stem from legends and practices from ancient times. Legend tells of a village, thousands of years ago, that was ravaged by Nian, an evil monster, one winter’s night. The following year the monster returned and again ravaged the village. Before it could happen a third time, the villagers devised a plan to scare the monster away.

The color red protects against evil. Red banners were hung everywhere. Firecrackers were set off, and people banged on drums and gongs creating loud noises to scare the beast away. The plan worked. The celebration lasted several days during which people visited with each other, exchanged gifts, danced, and ate tasty food. Today, celebrations last two weeks.

The red posters with poetic verses on it were initially a type of amulet, but now it simply means good fortune and joy. Various Chinese New Year symbols express different meanings. For example, an image of a fish symbolizes “having more than one needs every year”. A firecracker symbolizes “good luck in the coming year”. The festival lanterns symbolize “pursuing the bright and the beautiful.”

Preparing for the New Year

Spring cleaning is started about a month prior to the new year and must be completed before the celebrations begin. All the negativity and bad luck from the previous year must be swept out of the house.

Many people clean their homes to welcome the Spring Festival. They put up the red posters with poetic verses on it to their doors, Chinese New Year pictures on their walls, and decorate their homes with red lanterns. It is also a time to reunite with relatives so many people visit their families at this time of the year.

People also get haircuts and purchase new clothing. It symbolizes a fresh start. Flowers and decorations are purchased. Decorations include a New year picture (Chinese colored woodblock print), Chinese knots, and paper-cuttings, and couplets.

Flowers have special meanings and the flower market stocks up on:

- Plum blossom for luck

- Kumquats for prosperity

- Narcissus for prosperity

- Sunflowers to have a good year

- Eggplant to heal sickness

- Chom mon planta for tranquility

Offerings are made to the Kitchen God about a week before the New Year.

On The Eve of The Spring Festival

The Annual Reunion Dinner, Nian Ye Fan, is held on the eve of the festival. This is an important part of the celebration. Families come together and eat together. The food is symbolic. Many dishes have ingredients that sound the same as good tidings. In northern China, dumplings are served at midnight, they symbolize wealth.

In the evening of the Spring Festival Eve, many people set off fireworks and firecrackers, hoping to cast away any bad luck and bring forth good luck. Children often receive “luck” money. Many people wear new clothes and send Chinese New Year greetings to each other. Various activities such as beating drums and striking gongs, as well as dragon and lion dances, are all part of the Spring Festival festivities.

The dragon dance is a highlight in the celebrations. A team of dances mimic the movements of the dragon river spirit. Dragons bring good luck.

Lions are considered good omens. The lion dance repels demons. Each lion has two dancers, one to maneuver the head, the other to guide the back. Business owners offer the lions a head of lettuce and oranges or tangerines. The offerings hope to insure a successful year in business. Lettuce translates into “growing wealth” and tangerines and oranges sound like “gold” and “wealth” in Chinese. The lions eat the oranges, then spew them up and out into the hordes of people who eagerly tried to catch the them. After eating the lettuce, they spit out it out in a thousand pieces.

During the New Year

Red packets called Lai See Hong Bao (or Hongbao) with money tucked inside are given out as a symbol of good luck. The amount is an even number as odd numbers are regarded as unlucky.

- Bright red lanterns are hung.

- Brooms and cleaning material are put away. No cleaning takes place during the holiday so no good luck is swept out of the home.

- During the New Year celebrations people do not fight and avoid being mean to each other, as this would bring a bad, unlucky year.

- Bright colors and red are worn.

- Everyone celebrates their birthday this day and they turn one year older.

- Traditional red oval shaped lanterns are hung.

The end of the New Year is celebrated with the Lantern Festival.

Top Ten Taboos for The Chinese New Year

The Spring Festival is a time of celebration. It’s to welcome the new year with a smile and let the fortune and happiness continue on. At the same time, the Spring Festival involves somber ceremonies to wish for a good harvest. Strict rules and restrictions go without saying.

To help you with that, here are the top 10 taboos during the Chinese New Year. Follow these and fortune will smile on you.

- 1. Do not say negative words

All words with negative connotations are forbidden! These include: death, sick, empty, pain, ghost, poor, break, kill and more. The reason behind this should be obvious. You wouldn’t want to jinx yourself or bring those misfortunes onto you and your loved ones.

- 2. Do not break ceramics or glass

Breaking things will break your connection to prosperity and fortune. If a plate or bowl is dropped, immediately wrap it with red paper while murmuring auspicious phrases. Some would say 岁岁平安 (suì suì píng ān). This asks for peace and security every year. 岁 (suì) is also a homophone of 碎, which means “broken” or “shattered.” After the New Year, throw the wrapped up shards into a lake or river.

- 3. Do not clean or sweep

Before the Spring Festival, there is a day of cleaning. That is to sweep away the bad luck. But during the actual celebration, it becomes a taboo. Cleaning or throwing out garbage may sweep away good luck instead.

If you must, make sure to start at the outer edge of a room and sweep inwards. Bag up any garbage and throw it away after the 5th day. Similarly, you shouldn’t take a shower on Chinese New Year’s Day.

- 4. Do not use scissors, knives or other sharp objects

There are 2 reasons behind this rule. Scissors and needles shouldn’t be used. In olden times, this was to give women a well-deserved break.

Sharp objects in general will cut your stream of wealth and success. This is why 99% of hair salons are closed during the holidays. Hair cutting is taboo and forbidden until Lunar February 2, when all festivities are over.

- 5. Do not visit the wife’s family

Traditionally, multiple generations live together. The bride moves into the groom’s home after marriage. And, of course, she will celebrate Chinese New Year with her in-laws.

Returning to her parents on New Year’s Day means that there are marriage problems and may also bring bad luck to the entire family. The couple should visit the wife’s family on the 2nd day. They’d bring their children, as well as a modest gift (because it’s the thought that counts).

- 6. Do not demand debt repayment

This custom is a show of understanding. It allows everyone a chance to celebrate without worry. If you knock on someone’s door, demanding repayment, you’ll bring bad luck to both parties. However, it’s fair game after the 5th day. Borrowing money is also taboo. You could end up having to borrow the entire year.

- 7. Avoid fighting and crying

Unless there is a special circumstance, try not to cry. But if a child cries, do not reprimand them. All issues should be solved peacefully. In the past, neighbors would come over to play peacemaker for any arguments that occurred. This is all to ensure a smooth path in the new year.

- 8. Avoid taking medicine

Try not to take medicine during the Spring Festival to avoid being sick the entire year. Of course, if you are chronically ill or contract a sudden serious disease, immediate health should still come first. Related taboos include the following ~ Don’t visit the doctor, Don’t perform/undergo surgery, Don’t get shots

- 9. Do not give New Year blessings to someone still in bed

You are supposed to give New Year blessings (拜年—bài nián). But let the recipient get up from bed first. Otherwise, they’ll be bed-ridden for the entire year. You also shouldn’t tell someone to wake up. You don’t want them to be rushed around and bossed around for the year. Take advantage of this and sleep in!

- 10. Chinese gift-giving taboos

It was mentioned above that you should bring gifts when paying visits. It’s the thought that counts, but some gifts are forbidden.

- Clocks are the worst gifts. The word for clock is a homophone (sounds like) “the funeral ritual”. Also, clocks and watches are items that show that time is running out.

- Items associated with funerals – handkerchiefs, towels, chrysanthemums, items colored white and black.

- Sharp objects that symbolize cutting a tie (i.e. scissors and knives).

- Items that symbolize that you want to walk away from a relationship (examples: shoes and sandals)

- Mirrors

- Homonyms for unpleasant topics (examples:green hats because “wear a green hat” sounds like “cuckold”, “handkerchief” sounds like “goodbye”, “pear” sounds like “separate”, and “umbrella” sounds like “disperse”).

Some regions have their own local taboos too. For example, in Mandarin, “apple” (苹果) is pronounced píng guǒ. But in Shanghainese, it is bing1 gu, which sounds like “passed away from sickness.”

These don’t just apply to the Spring Festival, so keep it in the back of your mind!

For the Spring Festival, these rules may seem excessive. Especially when you add in the cultural norms, customs and manners. But like a parent would say, they are all for your own good. Formed over thousands of years, these taboos embody the beliefs, wishes and worries of the Chinese people.

Foods For The New Year

Dishes may vary slightly according to regional and family customs. Dumplings (gau ji) are more commonly served in the north of China, while Hong Kong families often go for a dim sum meal.

Food symbolism goes back centuries in China, and is taken very seriously on special occasions such as Lunar New Year. All food items have their symbolic meanings which, for Hongkongers, are often derived from their Cantonese homonyms. For instance, the Cantonese word for lettuce – sang choi – sounds very similar to the phrase which means “growing wealth”. Of course, nothing considered “unlucky” is allowed near the dining table.

By carefully choosing the menu in this way, families will supposedly be able to increase their luck and manifest their wishes for the coming year, whether those be earning more money or having more children.

Red meat is not served and one is careful not to serve or eat from a chipped or cracked plate. Fish is eaten to ensure long life and good fortune. Red dates bring the hope for prosperity, melon seeds for proliferation, and lotus seeds means the family will prosper through time. Oranges and tangerines symbolize wealth and good fortune. Nian gao, the New Year’s Cake is always served. It is believed that the higher the cake rises the better the year will be. When company stops by a “prosperity tray” is served. The tray has eight sides (another symbol of prosperity) and is filled with goodies like red dates, melon seeds, cookies, and New Year Cakes.

Here the origins of some traditional Chinese festival foods and their often quirky symbolic meanings.

- Lettuce for the lion dance

No traditional Lunar New Year celebration is complete without the famous lion dance, which is thought to bring good luck and ward off evil spirits. Performers wearing the traditional lion costume normally dance through the streets to the sound of gongs and drums. When the lion briefly stops at houses and businesses along the way, it will “eat” lettuce that is hung up outside the doors, since the humble vegetable symbolizes “growing fortune”. Inside the head of the lettuce will often be a red envelope, further emphasizing its significance.

- Dried oysters and ‘hair vegetable’ stir-fry

This unusual but lucky dish is named ho see fat choy in Cantonese, which sounds a lot like the words meaning “flourishing business”. For an extra dose of luck, ho see (oyster) on its own sounds similar to the Cantonese for “good things” or “good business”, while fat choy (hair vegetable) sounds similar to “prosperity”, as in the traditional Lunar New Year greeting kung hei fat choi. What’s more, the expensive “hair vegetable”, which looks like strands of black hair, is actually a type of fungus. But that doesn’t put off Cantonese restaurants from serving the auspicious dish at Lunar New Year.

- Egg noodles, or yi mein

This classic dish of stir-fried egg noodles is often served at formal dinners during Lunar New Year and other festivals, as it symbolises longevity. The chef must not cut the noodle strands to preserve their length. For this reason, yi mein is often eaten at birthday celebrations too – kind of like the Chinese equivalent of a candle-lit birthday cake.

- Glutinous rice cake, or neen go

The Cantonese term for this traditional sticky treat sounds the same as the literal words “year high”, which symbolize the promise of a better year to come. Families may eat this for several reasons: wanting to have a higher income, higher social status or even more children. Rice cake can be cooked in a variety of ways, and can be sweet or savory. Historical records date the yearly custom to at least 1,000 years ago, in the days of the Liao dynasty (AD907-1125). If there’s one thing that is unmissable from every family’s Lunar New Year feast in all parts of China and Hong Kong, it must be this dish.

- ‘Basin food’, or poon choi

Originating from the walled villages of the New Territories, this traditional celebratory dish soon spread throughout Hong Kong and later China. Legend has it that the early settlers in the New Territories would pool together their most prized ingredients – meat and seafood – in a big wooden washbasin and cook them to be served to the whole village. The communal dish required huge efforts of co-ordination and manpower to cook, so it quickly became associated with celebrations and religious rituals. Each village had its own secret poon choi recipe consisting of various ingredients layered in a particular order in the pot, but the dish is now found in most Cantonese restaurants on special occasions.

- Lotus root soup, or leen gnau tong

The fleshy, tuber-like roots of the lotus flower have been a staple of Chinese cooking for millennia, and traditionally symbolise “abundance”, since the Cantonese term sounds like “having [money] year after year”. The ingredient is also prized for its supposed “cooling” effect on the body, according to traditional Chinese medicine. Lotus root soup, or alternatively stir-fried lotus root, is commonly eaten at Lunar New Year for these reasons.

- Dim sum

Another Cantonese food tradition that is now common in the West is dim sum. The phrase literally means “a light touch of the heart” or “a little bit of heart”. This reflects the care and attention put into each bite-sized dish that is shared between the table, such as har gau (shrimp dumplings), various types of filled buns, and cheung fun (rice noodle rolls). Like a Chinese take on brunch, dim sum is often served at lengthy afternoon yum cha sessions in tea houses. But Hongkongers often go for an even more lavish version of this meal around Lunar New Year.

Auspicious Greetings

The Chinese New Year is often accompanied by loud, enthusiastic greetings, often referred to as auspicious words or phrases. New Year couplets printed in gold letters on bright red paper is another way of expressing auspicious new year wishes. The most common auspicious greetings and sayings consist of four characters, such as the following:

- 金玉滿堂 Jīnyùmǎntáng –

“May your wealth [gold and jade] come to fill a hall” - 大展鴻圖 Dàzhǎnhóngtú –

“May you realize your ambitions” - 迎春接福 Yíngchúnjiēfú –

“Greet the New Year and encounter happiness” - 萬事如意 Wànshìrúyì –

“May all your wishes be fulfilled” - 吉慶有餘 Jíqìngyǒuyú –

“May your happiness be without limit” - 竹報平安 Zhúbàopíng’ān –

“May you hear [in a letter] that all is well” - 一本萬利 Yīběnwànlì –

“May a small investment bring ten-thousandfold profits” - 福壽雙全 Fúshòushuāngquán –

“May your happiness and longevity be complete” - 招財進寶 Zhāocáijìnbǎo –

“When wealth is acquired, precious objects follow”

These greetings or phrases may also be used just before children receive their red packets, when gifts are exchanged, when visiting temples, or even when tossing the shredded ingredients of yusheng particularly popular in Malaysia and Singapore. Children and their parents can also pray in the temple, in hopes of getting good blessings for the new year to come.

Sources:

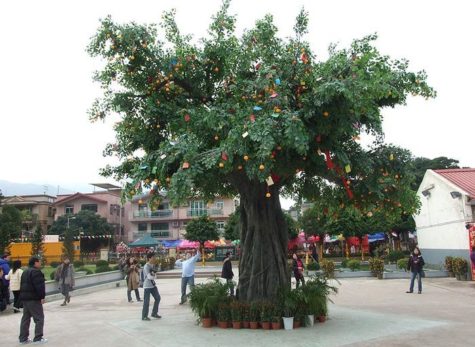

Every year, Lam Tsuen holds the Hong Kong Well-Wishing Festival. It part of the Chinese New Year celebration which attracts hundreds of thousands local citizens and tourists from all over the world. (In 2019, the festival runs from February 5 through March 3rd). Various activities at the festival include throwing wishing placard, setting wishing lanterns to make wish, joining international float exhibition, shopping in food carnival and setting lantern light to celebrate new born babies.

The Lam Tsuen Wishing Trees are a popular shrine in Hong Kong located near the Tin Hau Temple in Fong Ma Po Village, Lam Tsuen. The two banyan trees are frequented by tourists and locals during the Lunar New Year. Every year, wish-makers flood to Lam Tsuen for good fortune. The Lam Tsuen Wishing Trees are said to have the magic power to make a wish real.

The Lam Tsuen Wishing Tree was originally a camphor tree and later a redbud tree. The present Lam Tsuen Wishing Tree refers to an at least 200 year old banyan tree at the entrance of Lam Tsuen. There is also a newly planted banyan tree inside the village and a plastic Wishing Tree.

Lam Tsuen Wishing Tree has long been regarded as a deity by locals, who light candles and burn joss sticks at the root to worship the god. It is a tradition to make red or yellow papers on which people would write down their names, dates of birth and wishes, and roll the papers and tie them with weights (usually an orange) and finally toss them up onto the Wishing Tree. The paper scrolls are called “Bao Die.” Legend has it that if the “Bao Die” does not fall down, a wish would come true. Otherwise, the wish is said to be too greedy.

The Lam Tsuen Wishing Tree at the entrance was covered with “Bao Die” all the year around. As a result, it became extremely fragile. This practice was discouraged by the authorities after 12 February 2005, when one of the branches gave way and injured two people. Instead, wooden racks are set up in place for joss papers to be hung while a period of conservation is imposed to help these trees recover and flourish. Due to the lack of attractiveness of the attraction, A new plastic tree from Guangzhou was purchased in late 2009, plastic mandarin oranges are now only allowed to be tied to the branches. The tradition was able to continue since then.

There are four wishing trees in Lam Tsuen. Different trees symbolize various wishes. The first tree prays for career, academic and wealth. The second tree is for marriage and pregnancy. For the third tree, it states anything can be prayed. Yet, the fourth tree is believed to be most special. It is a fake 25-foot wishing tree made of plastic. Most people make wishes on the plastic Wishing Tree. This plastic fake wishing tree allows worshipers to throw their wishes to the tree.

A traditional “ Bao Die “ includes an orange and it ties with a yellow paper. Worshipers can write their name, date of birth and wishes on the yellow paper and throw it to the wishing tree. If you can successfully throw the “Bao die” and it hangs up on the tree or its branches, the myth said your wishes can come true. However, if it drops, the legend reckoned that your wishes are too greedy. But still, if the “wishes” drop, do not give up, try more and keep throwing until you make your wishes success.

There are lots of interesting stories about Lam Tsuen Wishing Tree. Lam Tsuen wishing tree was an ordinary camphor tree where a tablet for enshrining and worshipping Pak Kung was placed. As years passed, the branches and leaves gradually withered and eventually it became a hollow tree. People started to believe that Lam Tsuen wishing tree was magical after a legend: a man whose son had had a slow learning progress made a wish to a hollow tree. After that, his son’s academic performance has shown drastic improvement.

Another popular legend goes that the original wishing tree was huge with holes in the trunk. When people came to worship it and burn joss sticks, there would be oils flowing down form the holes. Unfortunately, the tree broke down after a fire accident. Surprisingly, before its death, two redbud blossoms appeared on the tree and grew rapidly. Soon the two blossoms were even bigger than the whole wishing tree.

In 2011, a Wishing Well was founded beside the wishing trees. The Wishing Well is a rectangle water channel flanked by glass with a length of 4 meters. The public can write down their wishes on paper, put it into a lotus-like lamp and drift the lamp on water to make a wish.

Sources:

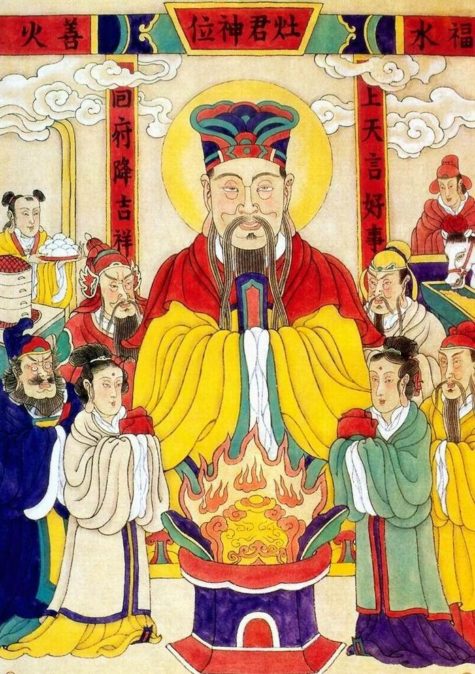

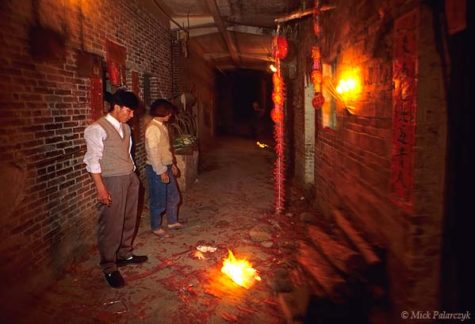

The Xiao Nian Festival (Little New Year) or the Kitchen God Festival occurs approximately a week before the Chinese New Year. The dates vary depending on the region, and from year to year.

It is believed that people in northern China celebrate it on the twenty-third day of the twelfth lunar month, while the people in southern China celebrate it on the twenty-fourth. Along with location, traditionally the date may also be determined by one’s Profession. For example, “feudal officials made their offerings to the Kitchen God on the twenty-third, the common people on the twenty-fourth, and coastal fishing people on the twenty-fifth”.

In 2019, in Taiwan, the festival will be celebrated on January 29.

It is believed that just before Chinese New Year, the Kitchen God returns to Heaven to report the activities of every household over the past year to Yu Huang, the Jade Emperor. Once in Heaven, the words of the Kitchen God influences the amount of prosperity and abundance that each family will have bestowed on them in the new year. The Jade Emperor, emperor of the heavens, either rewards or punishes a family based on Zao Jun’s yearly report.

In order to ensure that the Kitchen God speaks sweetly of the family, offerings of incense and bowls of ‘sweet treats’ such as ripe melons, honey, glutinous cakes, and sugar candies are presented for his delight before his image is burned and his journey begins.

Gold and silver ‘ingots’ fashioned from paper are also offered, and little paper-mache sedan chairs are sometimes provided to offer comfort on the journey to Heaven.

On this day, the lips of Zao Jun’s paper effigy are often smeared with honey to sweeten his words to Yu Huang (Jade Emperor), or to keep his lips stuck together. Incense and candles are lit around the house. Sticky sweets are left for the Kitchen God, usually on an alter or shrine. The stickier the candy the better, so the god’s mouth sticks closed and he can’t speak poorly of the family. According to custom, men must leave the sweets.

To send the god on his way, his picture is taken outside and the effigy is burned and replaced by a new one on Chinese New Year’s Day. Firecrackers are often lit as well, to speed him on his way to heaven. If the household has a statue or a nameplate of Zao Jun it will be taken down and cleaned on this day for the new year.

In days leading up to the Lunar New Year, people clean their houses, decorate their homes with paper cuttings, couplets and written blessings, and prepare festival food. After the cleaning is done, homes are decorated in red papercuts and posters, and fresh flowers.

In order to establish a fresh beginning in the New Year, families must be organized both within their family unit, in their home, and around their yard. This custom of a thorough house cleaning and yard cleaning is another popular custom during “Little New Year”. It is believed that in order for ghosts and deities to depart to Heaven, both their homes and “persons” must be cleansed. Lastly, the old decorations are taken down, and there are new posters and decorations put up for the following Spring Festival.

According to traditional Chinese culture, the kitchen god returns from heaven on the eve of Spring Festival, so the sacrifices for the god are served until the day he returns.

How Zao Jun Became The Kitchen God

Though there are many stories on how Zao Jun became the Kitchen God, the most popular one dates back to around the 2nd Century BC. Zao Jun was originally a mortal man living on earth whose name was Zhang Lang. He eventually became married to a virtuous woman, but ended up falling in love with a younger woman. He left his wife to be with this younger woman and, as punishment for this adulterous act, the heavens afflicted him with ill-fortune. He became blind, and his young lover abandoned him, leaving him to resort to begging to support himself.

Once, while begging for alms, he happened across the house of his former wife. Being blind, he did not recognize her. Despite his shoddy treatment of her, she took pity on him and invited him in. She cooked him a fabulous meal and tended to him lovingly; he then related his story to her. As he shared his story, Zhang Lang became overwhelmed with self-pity and the pain of his error and began to weep.

Upon hearing him apologize, Zhang’s former wife told him to open his eyes and his vision was restored. Recognizing the wife he had abandoned, Zhang felt such shame that he threw himself into the kitchen hearth, not realizing that it was lit. His former wife attempted to save him, but all she managed to salvage was one of his legs.

The devoted woman then created a shrine to her former husband above the fireplace, which began Zao Jun’s association with the stove in Chinese homes. To this day, a fire poker is sometimes referred to as “Zhang Lang’s Leg”.

Alternatively, there is another tale where Zao Jun was a man so poor he was forced to sell his wife. Years later he unwittingly became a servant in the house of her new husband. Taking pity on him she baked him some cakes into which she had hidden money, but he failed to notice this and sold the cakes for a pittance. When he realized what he had done he took his own life in despair.

In both stories Heaven takes pity on Zhang Lang’s tragic story. Instead of becoming a vampirish hopping corpse, the usual fate of suicides, he was made the god of the Kitchen, and was reunited with his wife.

Another possible story of the “Stove god” is believed to have appeared soon after the invention of the brick stove. The Kitchen God was originally believed to have resided in the stove and only later took on human form.

During the Han Dynasty, it is believed that a poor farmer named Yin Zifang, was surprised by the Kitchen God who appeared on Lunar New Year as he was cooking his breakfast. Yin Zifang decided to sacrifice his only yellow sheep. In doing so, he became rich and decided that every winter he would sacrifice one yellow sheep in order to display his deep gratitude.

Source: