Egyptian Festivities

The 5 Epagomenal Days (6 during leap years) were inserted into the Egyptian Calendar which had been 360 days long. These days were reserved as birthdays for the gods. The first, third, and fifth of these days were considered unlucky by the Egyptians.

The legend behind the days holds the Nut had been forbidden to have children on any day of the year by her husband Geb. Thoth, upon hearing this, gambled with the moon-god for a fraction of his light. Thoth won and he created the additional 5 days for Nut so she could bear children on these days “not of the year.”

They are as follows:

- July 27 – 1st Epagomenal Day – Birthday of Osiris

- July 28 – 2nd Epagomenal Day – Birthday of Horus

- July 29 – 3rd Epagomenal Day – Birthday of Set

- July 30 – 4th Epagomenal Day – Birthday of Isis

- July 31 – 5th Epagomenal Day – Birthday of Nephthys

Note:

These dates come from Traci de Regulla in The Mysteries of Isis. She took her dating from Dr. Robert Brier’s Ancient Egyptian Magic. There is a great deal of dispute when it comes to calculating the dates of Egyptian festivals due to problems in their calendar system (it was only 360 days for some period of time).

July 19 was a very important date in ancient Egyptian Cosmology. Known as ‘The Opening of the Year,” or the “Sothic New Year,” it was celebrated with a festival known as “The Coming of Sopdet.”

The oldest festival in ancient Egyptian history, the celebration of The Opening of the New Year began with the rising of Sirius who appeared as the goddess Isis cloaked in robes of brilliant light.

The sky is serene. Sothis lives. She shines, a peaceful flame.

Unas lives eternal as the son of Sothis,

As the child of Isis, as a child of Light,

As Earth is child of the Cosmos.

Unas is pure. She is pure,

As are all the gods whoever lived since the beginning of time

In the worlds above and in the worlds below.

They have been born the Imperishable Stars

Living within the Meshetiu, which shall never die.

~Pyramid Text Utterance 302

Sirius forms a part of the constellation Canis Major, sometimes referred to as the Dog Star. Of all the stars in the sky throughout the year, Sirius shines the brightest. The Greeks called the star Sothis, meaning “The Soul of Isis”. The Egyptians called her Sept or Sopdet, referring to the concept of preparing for the future. The ancient feast day name Per Sopdet may be translated as T”he Coming Forth of the Goddess.”

On this day Sirius, the “Dog Star”, rose together with Sun and announced the annual flooding of Nile River. The lands were watered and a black layer of slime covered them, providing humidity and fertilizer for next year’s harvest: the nation would not suffer of hunger. Thus it was the first year of the mystical Egyptian year, symbolizing transmutation and fertility.

Note: The actual date of this event in ancient Egypt is different than the current date because the date slowly varies within the Gregorian calendar, owing to its omission of three leap years every four centuries. It presently occurs on 3 August.

Ancient Egyptian Rites and Festivities

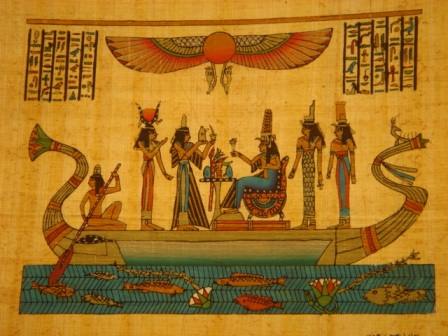

When Sirius reappeared as the morning star, the altars at the Isis temples of Philae, Karnak, and Dendera opened early. The portals and sanctuaries were aligned so precisely with the heavenly bodies that the predawn starlight of Sirius was projected onto the cult statue of the goddess. Thus began a season of preparation for the coming agricultural year and a celebration of the flood and fecundity of earth.

New Year’s Day in every temple across the land began with the lighting of the wicks for the temple fires. The glowing lamplight symbolized the eternal life of the spirit world and the flame’s earthly burning became a mirrored image of the glittering light of Sothis in the sky.

The lifting of the fires was usually followed by an offering of bread and prayers glorifying the dead, enacted in the northern corner of the temple – the northern region being linked with the souls of the ancestors, the Imperishable Ones who were the circumpolar stars.

When the Opening of the year or Wept Renpet was celebrated, it was also a day to celebrate the traditional birthday of the king and later the Pharoah – no matter the true date of his birth. The New Year’s Feast was an important festival in the life of the Egyptian ruler. It involved his ritually hoeing the ground and breaking the dirt clods in preparation for the sowing that would follow the receding waters.

The water stands and fails not, and the Nile carries a high flood. The days are long, the nights have hours, and the months come aright. The Gods are content and happy of heart, and life is spent in laughter and wonder.

~Prayer from the Sallier Papyrus

The galleries inside the pyramids point to the heavenly position of Sirius on such a day. Sirius was both the most important star of ancient Egyptian astronomy, and one of the Decans. Decans are star groups into which the night sky was divided, with each group appearing for ten days annually. The first night that Sirius is seen, just before dawn (heliacal rising) was noticed every year during July, and the Egyptians used this to mark the start of the New Year.

In fact, the “Sothic Rising” only coincided with the solar year once every 1460 years. The Roman emperor Antoninus Pius had a commemorative coin made to mark their coincidence in AD 139. The Sothic Cycle (the periods between the rising of the star) have been used by archaeologists trying to construct a chronology of Ancient Egypt.

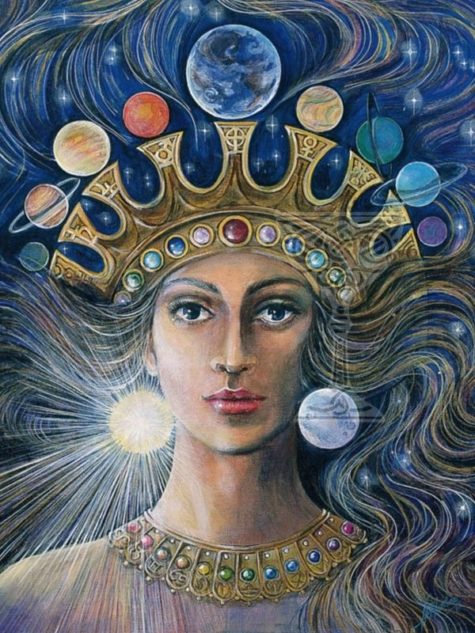

About Sopdet

Sirius was named Sothis by Egyptians and from archaic ages it symbolized eternity and fertility. As early as the 1st Dynasty, she was known as ‘the bringer of the new year and the Nile flood. Sopdet took on the aspects of a goddess of not only the star and of the inundation, but of the fertility that came to the land of Egypt with the flood. The flood and the rising of Sirius also marked the ancient Egyptian New Year, and so she also was thought of as a goddess of the New Year.

- Themes: Fertility, Destiny, Time

- Symbols: Stars and Dogs.

Not just a goddess of the waters of the inundation, Sopdet had another link with water – she was believed to cleanse the pharaoh in the afterlife. It is interesting to note that the embalming of the dead took seventy days – the same amount of time that Sirius was not seen in the sky, before it’s yearly rising. She was a goddess of fertility to both the living and the dead.

In the Pyramid Texts, she is the goddess who prepares yearly sustenance for the pharaoh, ‘in this her name of “Year”‘. She is also thought to be a guide in the afterlife for the pharaoh, letting him fly into the sky to join the gods, showing him ‘goodly roads’ in the Field of Reeds and helping him become one of the imperishable stars. She was thought to be living on the horizon, encircled by the Duat.

The reigning Egyptian Queen of the Constellations, Sopdet lives in Sirius, guiding the heavens and thereby human destiny. Sopdet is the foundation around which the Egyptian calendar system revolved, Her star’s appearance heralding the beginning of the fertile season. Some scholars believe that the Star card of the Tarot is fashioned after this Goddess and Her attributes.

The long, hot days of summer are known as the ‘Dog Days‘ because they coincide with the rising of the dog star, Sirius. In ancient Egypt this was a welcome time as the Nile rose, bringing enriching water to the land.

Activities for Today

Go outside tonight and see if you can find Sirius. When you spy it, whisper a wish to Sopdet suited to Her attributes and your needs. For example, if you need to be more timely or meet a deadline, she’s the perfect Goddess to keep things on track.

If you’re curious about your destiny, watch that region of the sky and see if any shooting stars appear. If so, this is a message from Sopdet. A star moving on your right side is a positive omen; better days are ahead. Those on the left indicate the need for caution, and those straight ahead mean things will continue on an even keel for now. Nonetheless, seeing any shooting star means Sopdet has received your wish.”

- Recall a new beginning

Recall a time in your life when you were starting anew, perhaps after a divorce or when moving into a new home. Perhaps your new life followed the birth of a child or a change in career. Investigate what had to die in your old life in order for the new life to emerge. How did that feel as you stood poised on the brink of change?

- Explore your creativity

Explore what it means to be creative. Think about the most creative times in your life. Where did you live? How different did life seem then from the way it seems now? How was your time structured? What were you thinking, desiring, telling yourself on a daily basis? Can you duplicate any of that in your life now?

- Ten Things

Make a list right now of ten things you want to manifest in the next six months. Be specific. Plant three seeds for each thing you want to manifest, then tend to them. Mark each seed with a popsicle stick to indicate what goal you are germinating, so that when you water the plant, you stay focused on what you are nurturing within yourself.

Write a brief prayer to one of the abundance goddesses – Isis, Hathor, or Anket – asking her to guide you and oversee your fecundity. Say your prayer each time you tend your plants.

Sources:

- Tour Egypt

- Journeying To The Goddess

- Feasts of Light

The festival calendar of ancient Egypt, as it appears to us now, spans three thousand years of Egyptian history and probably was being recorded, observed, and manipulated many thousands of years before that. In those three millennia a great many political and religious changes affected the designated feast days. Some feasts fell out of favor, others were renamed, a few were entirely forgotten.

Many Egyptian feast days are moveable feasts, that is, they are lunar festivals timed to phases of the moon. Thus their occurrence might slip around from one year to the next. This is similar to how Easter Sunday, (the first Sunday following the first full moon after the vernal equinox), falls on a different date every year.

The Calendar

In any true sense it would be impossible for us to know the actual recurring dates of many of the festivals. We can, however, approximate the ancient dates. The Gregorian Calendar dates given here should not be taken as arbitrary or fixed, I think of them as a suggestion instead.

This particular calendar is from the book Feasts of Light. You may find that the dates of these various festivals are listed differently on other calendars. When planning a celebration in the Egyptian manner, use your intuition and your own understanding of the Lunar Calendar and the Wheel of the Year.

Season of Inundation – Akhet – Winter

During the Season of Inundation more major public festivals occurred than at any other time of the year, most of them related to fertility rites and abundance rituals. The feasts tended to occupy the general public during this time because the land was so flooded that little real work could be done.

Thuthi – The first month of winter

- 1 – The Rise of Sothis as Isis – July 19

- 1 – The Opening of the New Year – July 19

- 7 – The Feast of Anket – July 25

- 20 – The Inebriety of Hathor – August 7

Paopi – The second month of winter

- 5 – The Feast of Hathor and Min – August 22

- 15 – The Opet Festival – September 1

- 21 – Neith Goes Forth to Atum – September 7

Hethara – The third month of Winter

- 1 – Hathor’s Birthday Feast – September 17

- 17 – The Lamentations of Isis – October 3

- 21 – The Feast Day of Ma’at – October 8

- 30 – Opening the Bosom of Women – October 16

- 30 – The Feast of Isis in Busiris – October 16

Koiak – The fourth month of Winter

- 17 – The Plucking of the Papyrus for Hathor – November 2

- 27 to 29 – The Osirian Mysteries – November 12 to 14

- 27 – Isis Seeks the Body of Osiris – November 12

- 28 – Isis Grieves the Loss of Osiris – November 13

- 29 – Isis Rejoices as She Finds Osiris – November 14

Season of Sowing – Pert – Spring

Once the waters receded and work in the fields began, the Sowing season was the busiest time of the year.

Tybi – the first month Spring

- 19 and 20 – The Voyage of Hathor to Nubia – December 4 and 5

- 20 – Bast Goes Forth from Bubastis – December 5

- 28 to 30 – The Voyage of Hathor to Egypt and Her Father – December 13 to 15

Mechir – the second month of Spring

- 1 to 3 – The Voyage of Hathor to Egypt and Her Father( continued) – December 16 to 18

- 6 – The Feast of Isis the Black Cow – December 21

- 6 – The Festival of Raising the Djed of Osiris – December 21

- 10 – The Birth of Ra, Child of Nut – December 25

- 10 – The Birth of Horus, Child of Isis – December 25

- 19 – Isis Returns from Phoenicia with Osiris – January 3

- 21 – The Voyage of Hathor to See Her Seven Sisters – January 4

- 24 – Isis Greets Min in Coptos – January 8

Pamenot – the third month of Spring

- 5 – The Brilliant Festival of the Lights of Neith – January 19

Parmuti – the fourth month of Spring

- 20 – The Blessing of the Fleets by Isis – March 5

- 28 – Isis Births Horus the Younger – March 13

- 28 – Hathor Births Ihy – March 13

Season of the Harvest – Shemu – Summer

The growing season was quickly followed by the Harvest season. But during the final months of the year, when the harvest had ended and the land was dry, the festivals began again, mostly in anticipation of the coming Inundation.

Pachons – the first month of Summer

- 1 – The Feast of the Hand of the God – March 16

- 6 – The Pregnancy of Isis / Nut – March 21

- 15 – The Festival of Renenutet – March 30

- 19 – Isis Finds Osiris – April 3

Payni – the second month of Summer

- 1 – The Great Festival of Bast at Bubastis – April 15

- 26 – The Going Forth of Neith along the Water – May 10

Epiphi – the third month of Summer

- 1 – The Hierogamos of Hathor and Horus – May 15

- 4 – The Conception of Horus – May 18

- 5 – Hathor Returns to Punt – May 19

- 7 – The Sailing of the Gods after the Goddess – May 21

- 30 – The Festival of Mut: Feeding of the Gods – June 13

Mesore – the fourth month of Summer

- 3 – The Feast of Raet – June 16

- 3 – The Feast of Hathor as Sothis – June 16

The Epagomenal Days

The Egyptian year was divided into twelve months of thirty days each, which means that each year was about five days short of the astronomical year. To compensate for this difference, five extra days were added to the year, and (according to this particular calendar) are designated as follows:

- The Birthday of Osiris – July 14

- The Birthday of Horus the Elder – July 15

- The Birthday of Seth – July 16

- The Birthday of Isis (The Night of the Cradle) – July 17

- The Birthday of Nephthys – July 18

This little-known festival was celebrated at the Temple of Edfu. It doesn’t sound like a Goddess festival, but it is, for the Hand of the God was called Iusaas or Iusaaset. This Goddess, honored in the city of Heliopolis wore a scarab beetle on her head, the symbol of transformation. She was the counterpart of the god Atum, literally his hand.

In the Pyramid Texts an early genesis story recounts how the divine All, the androgynous Atum, created the world from the substance of himself it reads:

“Atum was creative in that he proceeded to masturbate with himself in Heliopolis; he put his penis in his hand that he might obtain the pleasure of emission thereby, and there were born brother and sister ~ that is, Shu and Tefnut.”

Like Isis with whom she is sometimes identified, Iusaaset (whose name means “She Comes While She Grows Large,” a name underscoring the masturbation motif), had a sister called Nebet-hotepet, who is linked with Nephthys. Nephthys name probably means The House of Offering” perhaps referring to the womb of the All which is offered for use during the conception, gestation, and birth of the world.

It is no accident that the Feast of the Hand of the God occurs between two other birth festivals (The Birth of Horus the Younger and the Pregnancy of Nut). It is, after all, a season near the vernal equinox when light has returned to the sky and the days grow in length. It is a time when the world is made new again, when the Hand of the God brings forth life from the waters of chaos. It represents the union of masculine and feminine energies to create and sustain life.

Festival Celebration Ideas

It is unclear how the festival was celebrated in ancient Egypt. Some historians suggest that there might have been sexual rites or ritual marriages. This might be a good time for sex magick, if that is something that you enjoy.

In the Temple of Dendera, which has been called the Castle of the Menat, The Feast of the Hand of the God might have been a day in which all pregnant, including the wives and concubines of the pharaoh, might come to the temple to be blessed. Perhaps the day began with a sunrise devotion to the goddess as Mother of the All.

Perhaps amid the strains of beautiful music, the priestesses touched each pregnant woman’s belly and breasts, or anointed their faces with perfume, or even milk, whispering words of welcome to the unborn children, saying the same words priestesses used to great the nomarch Senbi, “for your spirit, behold the menat of your mother, Hathor. May she make you flourish as long as you desire.”

Hymn to Isis

Enchantress and wife, she stamps and spins.

She raises her arms

to dance. From her armpits arises a hot perfume

that fills the sails of boats along the Nile.

She stirs breezes that make the sailors swoon

and opens the eyes of statues. Under her spell,

I come to myself; under her body I come to life.

Dawn breaks through the diaphanous weave of

her dress. She dances and draws down heaven.

Sparks scatter from her heels and on earth tumbles

forth an expanse of stars…”

Activities For Today

Here are some ideas you might want to explore today. They can, of course, be done at any time.

- Get Creative

The act of creation can be playful, fun, colorful, and messy. Do a Google search and you will find a lot of simple ideas for how to make art with hand prints. This is a fun activity for kids, and the child within.

- Journaling

In your journal, explore what it means to you to be a cocreator of the universe with the Divine.

- Make a Collage

Gather some magazines that you feel free to cut up. Leaf through them, searching for images that appeal to you. Perhaps the images hint at where you focus your energies or where you will focus your energies in the future. Cut out the images and lay them aside. Outline your hands on a sheet of paper.

Slowly, meditatively, begin to trim, sort, and paste the images onto the image of your own hands. You might use the right hand for things that you already create and the left hand for things you will create in the future. Around the edges of these hands, write a myth of yourself as the creator of this world.

- Make a Physical Connection

Our bodies are instruments of our connection to the physical universe. Reestablish a connection to your body’s natural wisdom. With crayon, outline your body on a long sheet of butcher paper.

Begin at the top of your head and record what each part of your body remembers: your hair, your cheeks, your nose, etc. Try to list both joys and sorrows. When you find a part of your body that holds many strong memories, make not of it.

Later, return to that spot and write a dialog with that part of your body.

Source: Feasts of Light

February 17 is the Feast of Shesmu, Eqyptian god of execution, slaughter, blood, embalming oil, wine, and perfume. Old Kingdom texts mention a special feast celebrated for Shesmu: young men would press grapes with their feet and then dance and sing for Shesmu.

Shesmu is also known as:

- Shezmu, Schezemu, Schesmu, Shesemu, Shezmou, Shesmou, Sezmu and Sesmu.

Shesmu was a god with a contradictory personality. On one hand, he was lord of perfume, maker of all precious oil, lord of the oil press, lord of ointments and lord of wine; a celebration deity.

On the other hand, Shesmu was very vindictive and bloodthirsty. He was also lord of blood, great slaughterer of the gods and he who dismembers bodies. In Old Kingdom pyramid texts several prayers ask Shesmu to dismember and cook certain deities in an attempt to give the food to a deceased king. The deceased king needed the divine powers to survive the dangerous journey to the stars.

Shesmu had the head, fangs, and mane of a lion drenched in blood, and he wore human skulls around his waist. He could form into a man or falcon.

Shezmu did away with bad people, putting their heads through winepresses, draining them of their blood and turning it into wine on the order of Osiris. The bodies and blood of the dead gave sustenance for Unas, Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, and the last ruler of the Fifth dynasty from the Old Kingdom.

Due to its color, red wine became strongly identified with blood, and thus Shezmu was identified as lord of blood. Since wine was seen as a good thing, his association with blood was considered one of righteousness, making him considered an executioner of the unrighteous, being the slaughterer of souls. When the main form of execution was by beheading, it was said that Shezmu ripped off the heads of those who were wicked, and threw them into a wine press, to be crushed into red wine, which was given to the righteous dead.

Beheading was commonly carried out by the victim resting their head on a wooden block, and so Shezmu was referred to as Overthrower of the Wicked at the Block. This violent aspect lead to depiction, in art, as a lion-headed man, thus being known as fierce of face.

In later times, Egyptians used the wine press for producing oils instead of wine, which was produced by crushing under foot instead. Consequently, Shezmu became associated with unguents and embalming oils, and thus the preservation of the body, and of beauty.

The violent character of Shesmu made him a protector among the companions of Ra’s nocturnal barque. Shesmu protected Ra by threatening the demons and brawling with them.

Shezmu followed the commands of The God of The Dead. Though he seemed a fierce underworld deity, he offered protection to the virtuous. Shezmu offered red wine to those who had passed on.

The feast is no longer celebrated, but most Ancient Egyptian feasts were religious in nature. Bread, cakes, wine/beer, meat, and fowl would have been consumed, incense burned, and prayers offered to Shesmu.

Sources:

- Themes: Love; Fertility; Passion; Sexuality; Moon

- Symbols: Star; Moon; Lion; Dove

- Color: Gold

- Incense: Eucalyptus

Sometimes known as the sacred prostitute of Babylon, is the Babylonian goddess of fertility, sexual love, and war, Ishtar encompasses the fullness of womanhood, including being a maternal nurturer, an independent companion, an inspired bed partner, and an insightful adviser in matters of the heart.

Having descended from Venus (the planet that governs romance), she is the moon, the morning star, and the evening star, which inspire lovers everywhere to stop for a moment, look up, and dare to dream. Saturday is Ishtar’s traditional temple day, and her sacred animals include a lion and a dove.

Babylonians gave Ishtar offerings of food and drink on this day. They then joined in ritual acts of lovemaking, which in turn invoked Ishtar’s favor on the region and its people to promote continued health and fruitfulness.

That being said, allow yourself today to reflect on embracing your own sexual being. On a piece of paper, list things about your body and your sexuality that make you uncomfortable. Then, light a pink candle and send pink, healing light to any parts of yourself with which you have emotional discomfort. Embrace your sexual self for who you are and find peace within. After spending time for yourself, consider your own sexual relationships. Focus energy on things within them that are not right and comfortable for you. Send healing to those areas as well. Your sexual relationships should bring joy and pleasure into your life. Remember to be safe in them as well. Thank Ishtar for her presence in your life. Finish your meditations and enjoy the vibrancy of the day.

A magickal alternative, if you have no bed partner, is to use symbolism. Place a knife (or athame, a ritual dagger often representing the masculine divine or the two-edged sword of magick) in a cup filled with water. This represents the union of yin and yang. Leave this in a spot where it will remain undisturbed all day to draw Ishtar’s loving warmth to your home and heart.

If you have any clothes, jewelry, or towels that have a star or moon on them, take them out and use them today. Ishtar abides in that symbolism. As you don the item, likewise accept Ishtar’s mantle of passion for whatever tasks you have to undertake all day.

A Ritual For Ishtar’s Day

- Color: Pottery red, terra cotta

- Element: Earth

- Offerings: Grains. Stars. Give food to those who need it.

- Daily Meal: Wholegrain bread. Cooked grains. Milk and dairy products.

Altar: Set with a cloth of earthy red, and on it place a pitcher of milk and another of wine, bowls of wood and clay filled with grains, olives, figs, and dates, a star, and the figure of a lioness.

Ishtar Invocation

I beseech thee, Lady of Ladies,

Goddess of Goddesses,

Ishtar, queen of all cities,

Leader of all men.

Thou art the light of the world,

Thou art the light of heaven.

At thy name the earth and the heavens shake,

And the gods they tremble;

The spirits of heaven tremble at thy name

And the men hold it in awe.

Where thou glancest the dead come to life,

And the sick rise and walk;

And the mind that is distressed is healed

When it looks upon thy face.

Call and response:

For lo, I am the Keeper of the Storehouse

And I am generous to all men!

From my breasts nourishment spills

From my hands nourishment flows

From my heart nourishment streams

I am the Morning Star

I am the Evening Star

I am the Star of Heaven

And I give unto all humanity.

(After this, all should being the work of inventorying all the resources of the house, in Ishtar’s name, so that they may be used more efficiently and that it can be known what can be given to others out of generosity.)

Sources:

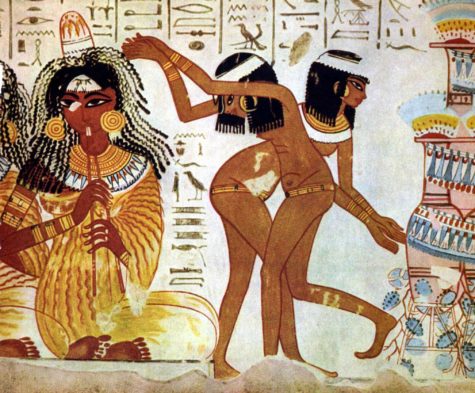

According to many pagan calendars, April 15 was the annual festival of Bast. This was Egypt’s most popular festival. A precursor of modern Mardi Gras, it was renowned for parties, revelry, and drunkenness. Herodotus, the Greek traveler and historian writing in the fifth century BCE, claimed that more wine was consumed in Egypt during this festival than during the entire rest of the year. Although many details are lost, Bastet’s festival celebrated female sexuality and generative power.

Boats sailed up the Nile toward Bubastis (her cult city). As each barge approached towns and settlements, it would halt and the mainly female celebrants on board would loudly hail local women congregating on the riverbanks. They would shout sexual obscenities to each other, dance wildly, and perform anasuromai, the ritual act of lifting up the skirts to expose the vulva, associated with laughter, healing, and defiance of grief.

For a socially acceptable way to celebrate:

- Colors: Pink, yellow, clay-color

- Element: Fire

- Daily Meal: Fish.

- Offerings: Give aid to an animal shelter. Give food to household cats.

Altar: Upon a cloth the color of clay, set ten lit candles of pink and yellow, and the figures of many cats. In the center should sit a figure of Bast, and a sistrum. The one who has been chosen to do the work of the ritual should pick up the sistrum before the invocation, with an obeisance to Bast, and it should be shaken after every sentence.

Invocation to Bast

O great Mistress of Cats,

Lady of pleasure in ancient times,

Your eyes sparkle with mischief

And you grant your favors capriciously,

Giving them only where the whim takes you.

Yet we who inhabit this strange world,

Below you yet in power over all your subjects,

We would ask your blessing on us

As we give our blessing to those who are in our mercy.

May we never forget, Lady of tame predators,

Who are not so tame as we might like to believe,

That when we are in a position of power

We should never forget the spirit of those beneath us.

Bless us with joy in life, Lady Bast,

And may we go to our graves

Never forgetting what it is like to play.

Hail Bast! (Repeat response)

Hail Bast! (Repeat response)

Hail Bast! (Repeat response)

For the rest of the afternoon, work should be done at an animal shelter, or spent playing with cats, which on this day alone is not shirking the work. Some folk of the House may choose to be cats themselves for this day; they need do no work, and it is lucky to pet them, but they must not stand on two legs or the spell will be broken. During this time, they must meditate on what it is to be in the strange predicament of the tamed predator who is dependent on the whims of humans

From:

- Encyclopedia of Spirits

- Pagan Book of Hours

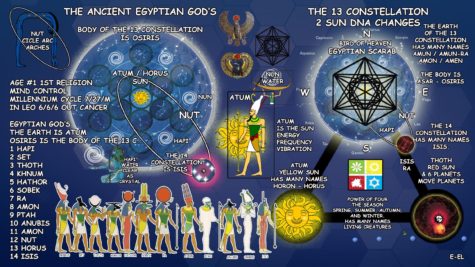

By the time writing first appeared (around 3100 B.C.E.) ancient Egyptian life centered around no less than three calendars. The lunar calendar, the civil calendar, and the Sothic calendar. These calendars were based on the celestial patterns of the moon, the sun, and the star Sirius, respectively.

The Lunar Calendar

The moon with its regular cycle became the oldest time keeper. Coinciding with a woman’s menstrual cycles, it was the perfect instrument to keep track of her and the animal’s fertile times and to record the patterns of life. No wonder the goddesses Isis and Hathor were associated with the moon.

The Solar Calendar

The civil calendars were solar based and used the movement of the sun across the sky to signal the approaching seasons. When roaming the countryside, chasing game, and gathering food gave way to the practice of agriculture, it became more important for our ancestors to master the signs of the growing seasons than to follow animal migration patterns.

Early agriculturists began to look up at the sky in an effort to learn when to prepare the ground, when to plant, and when to reap. Unlike lunar calendars, solar calendars marked the solstices (the longest and shortest days of the year), as well as the equinoxes (when the days and nights were of equal length).

In addition, seasonal changes that affected the growing season were predicted by observing the rise of certain constellations, particularly those constellations that followed the ecliptic (the apparent path of the sun through the heavens). Thus, the appearance of the twelve zodiacal constellations formed an important part of the civil and solar calendar.

Correcting The Inconsistencies

Because the moon cycles didn’t exactly match the sun cycles, five intercalary days, called Epagomenal Days, were eventually added to the calendar year. In Egypt those five days honored the births of the great neters (Supreme Deities) Osiris, Horus, Seth, Isis, and Nephthys. Even after the Epagomenal Days were added to the solar calendar, it was still inexact because the true year is actually a few hours longer than 365 days.

To determine exactly when the seasons would change and when to sow or harvest, the Egyptians began to track and observe all the heavenly bodies, including the moon, the sun, the constellations, and the brightest, most visible stars. By watching the sky over the years, people began to notice that just before dawn near the summer solstice, the rising of the Dog Star Sirius, the brightest star in the heavens.

The rising of this star was a better, more reliable predictor of the coming of the flood season than the solar calendar alone. When the star appeared, the flood waters flowing from the southern mountains and highlands appeared soon after. By observing Sirius, preparations for planting and sowing could be made well in advance. In addition, the regularity of the rise of Sirius most closely resembled the true length of the year.

The Sothic Calendar

The brilliant star Sirius, appearing in the constellation we know as Canis Major, was ancient Egypt’s most important star. The Egyptians called the star Sopdet and equated it with Isis, the powerful goddess of regeneration.

The Greeks called the star Sothis, later developing a so-called Sothic calendar that kept even more regular track of the years and the seasons, being most nearly 365.25 days. Even then the calendar still wasn’t perfect.Incremental changes were occurring due to the rotation of the earth, the tilt of the earth, and the procession of the equinoxes.

The Civil Calendar

By divine decree laid down in the mists of prehistory, the Egyptian priest-king swore never to alter the civil calendar, even though its solar-basted calculations were not keeping up with the changing seasons. The reason for this seemingly irrational adherence lay in the fact that the year had been divinely established by the god of wisdom and time, Thoth.

Thoth’s laws were the laws of the gods, and divine laws were considered unalterable. The real reason may have been that astrologer priests were tracking an even larger arc of time – a procession not of the sun and moon, but of the equinoxes – that resulted in a kind of calendar of the ages.

When the Greeks arrived in Egypt, however, they saw little value in maintaining such a cosmic calendar when the civil calendar was so woefully out of alignment. Once they established themselves as kings, the Ptolemaic Greeks believed that the time had come to alter Thoth’s divine law. They coerced the priests into adding an extra day every four years to even out the true calendar. The result created the leap year, which we use even to this day.

How The Egyptian Calendar Works

At first Egypt’s calendar seems hard to understand because we are conditioned to our own notions of month and season derived from the Romans. Really, the ancient Egyptian calendar is fairly simple. The year has twelve months, the months have three weeks, and each week has ten days. This represented the basic system of the lunar year.

Tacked on to the end of these 360 days were the five Epagomenal Days, added to create the 365 days of the solar year. The Epagomenal Days signaled the end of the year and were followed by the new year’s celebration, just as New Year’s Day follows New Year’s Eve in our calendar. But, whereas we begin counting in the winter month of January, the ancient Egyptians began counting at the rise of the Dog Star Sirius, which occurs in the middle of our summer.

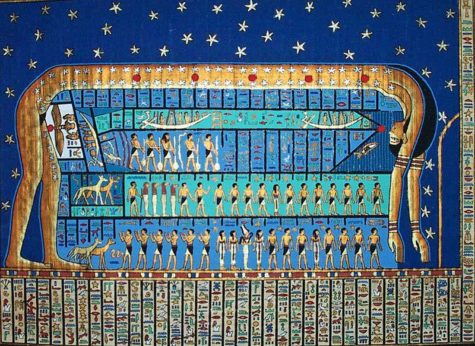

This system makes perfect sense because the new year signaled the beginning of a new agricultural cycle. When the Dog Star rose, the Nile flooded, and the parched earth was refertilized The sacred actions of the Nile River – its flooding, its retreat into its banks leaving fertile soil, and its eventual low flow creating drought conditions – determined not only the major festivals of the pharaoh and his people,but the three seasons of the year.

The Three Seasons

The ancient Egyptians did not celebrate four seasons of spring, summer, fall, and winter as we do. Rather, their three seasons were uniquely timed to the particular agricultural requirements in their geographic region. The three seasons were:

The ancient Egyptians did not celebrate four seasons of spring, summer, fall, and winter as we do. Rather, their three seasons were uniquely timed to the particular agricultural requirements in their geographic region. The three seasons were:

- Ahket – Innundation

Also called the Red Season, it extended from mid July to mid November, when most of the river valley and Delta were underwater.

- Pert – Sowing

Also called the Black Season, it extended from mid November to mid March, the equivalent to our spring, which the Egyptians called the Coming Forth.

- Shemu – Harvest

Also called the White Season, it extended from mid March to mid July when crops were harvested. By season’s end, everything was dry and the fields were scorched.

From: Feasts of Light

The great and supreme powers of ancient Egypt were the Gods and Goddesses of nature. The coming of the annual flood, the blossoming of the lotus, the rising of the brightest star in the sky, the disappearance of the moon, the eclipsing of the sun, the cutting of the wheat – all were occasions in which the Divine manifested on earth.

The religious life of the ancient Egyptians was marked by the celebration of the following kinds of sacred events:

- Festivals dedicated to a particular god or goddess which honored them through the public remembrance of their mythic lives.

- Festivals which honored the dead, bringing together a sense of the tribal community and the ancestral history and marking the cycles of time.

- Festivals which initiated the agrarian work cycles of preparing, sowing, and harvesting, as well as lying fallow.

In all probablity these seasonal festivals were determined by astronomical markers, such as the equinoxes, the solstices, and the rise of particular stars and constellations.

These were sacred events to which the Great Gods and Goddesses provided their blessings, for they were the manifestations of the cosmic cycle of nature. The will of the Gods was made known through the great pattern laid out in the sky by celestial phenomena.

There earliest festivals were those celebrating the mysteries of the Goddess in her appearance as the day and night sky, as both sun and moon. Most of the original ancient Egyptian feast days were celebrated at the new or the full moon. The ancient hieroglyph for “month” was the image of the moon itself. Apparently, the original festival calendar was lunar.

Of course, many Egyptian feast days are moveable feasts; that is, they are lunar festivals timed to phases of the moon. Thus, their occurrence might slip around from one year to the next. Other Egyptian festival dates were set by the motion of the stars, the planets, and the actions of the sun.

In any true sense it would be impossible for us to know the actual recurring dates of many of the festivals. We can, however approximate the ancient dates, which is what most Egyptologists do.

During the season of Inundation more major public festival occurred than at any other time of the year, most of them related to fertility rites and abundance rituals. The feasts tended to occupy the general public during this time because the land was so flooded that little real work could be done.

By comparison, the Sowing season had fewer festivals. Once the waters receded and work in the fields began, the Sowing season was the busiest time of year. The growing season was quickly followed by the Harvest season. But during the final months of the year, when the harvest had ended and the land was dry, the festivals began again, mostly in anticipation of the coming Inundation.

The festival calendar, as it appears to us now, spans three thousand years of Egyptian history and probably was being recorded, observed, and manipulated many thousands of years before that. In those three millennia a great many political and religious changes affected the designated feast days. Some feasts fell out of favor, others were renamed, a few were entirely forgotten.

From: Feasts of Light

The Festival of Navigation (March 5th) was an ancient Roman festival that celebrated Isis as the ruler over safe navigation, boats, fishing, and the final journey of life. At this festival, after an elaborate parade, a Ship of Isis filled with great offerings of incense, flowers, libations and small shrines was sent out to sea.

For an eyewitness description of this festival, visit this post: Navigium Isidis.

I do like the idea of sending out ships with offerings to Isis. And with that in mind, I’m sharing here a video tutorial on how to make a paper boat that floats on water. This small boat could be decorated with symbols or with petitions for guidance, filled small offerings, and then floated down a stream, creek, river, etc. If you don’t have access to water, you could ritually burn your boat on a bed of incense and fragrant herbs and allow the smoke to take your petitions and offerings to the goddess.