By the time writing first appeared (around 3100 B.C.E.) ancient Egyptian life centered around no less than three calendars. The lunar calendar, the civil calendar, and the Sothic calendar. These calendars were based on the celestial patterns of the moon, the sun, and the star Sirius, respectively.

The Lunar Calendar

The moon with its regular cycle became the oldest time keeper. Coinciding with a woman’s menstrual cycles, it was the perfect instrument to keep track of her and the animal’s fertile times and to record the patterns of life. No wonder the goddesses Isis and Hathor were associated with the moon.

The Solar Calendar

The civil calendars were solar based and used the movement of the sun across the sky to signal the approaching seasons. When roaming the countryside, chasing game, and gathering food gave way to the practice of agriculture, it became more important for our ancestors to master the signs of the growing seasons than to follow animal migration patterns.

Early agriculturists began to look up at the sky in an effort to learn when to prepare the ground, when to plant, and when to reap. Unlike lunar calendars, solar calendars marked the solstices (the longest and shortest days of the year), as well as the equinoxes (when the days and nights were of equal length).

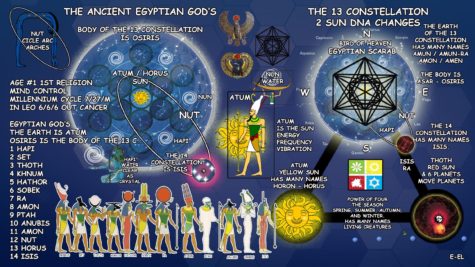

In addition, seasonal changes that affected the growing season were predicted by observing the rise of certain constellations, particularly those constellations that followed the ecliptic (the apparent path of the sun through the heavens). Thus, the appearance of the twelve zodiacal constellations formed an important part of the civil and solar calendar.

Correcting The Inconsistencies

Because the moon cycles didn’t exactly match the sun cycles, five intercalary days, called Epagomenal Days, were eventually added to the calendar year. In Egypt those five days honored the births of the great neters (Supreme Deities) Osiris, Horus, Seth, Isis, and Nephthys. Even after the Epagomenal Days were added to the solar calendar, it was still inexact because the true year is actually a few hours longer than 365 days.

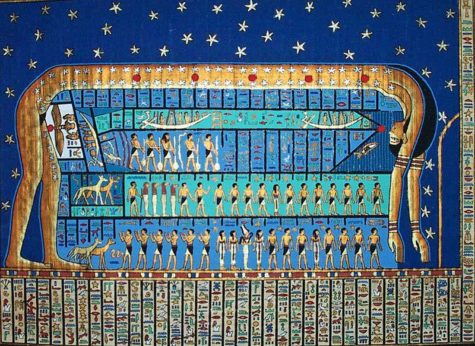

To determine exactly when the seasons would change and when to sow or harvest, the Egyptians began to track and observe all the heavenly bodies, including the moon, the sun, the constellations, and the brightest, most visible stars. By watching the sky over the years, people began to notice that just before dawn near the summer solstice, the rising of the Dog Star Sirius, the brightest star in the heavens.

The rising of this star was a better, more reliable predictor of the coming of the flood season than the solar calendar alone. When the star appeared, the flood waters flowing from the southern mountains and highlands appeared soon after. By observing Sirius, preparations for planting and sowing could be made well in advance. In addition, the regularity of the rise of Sirius most closely resembled the true length of the year.

The Sothic Calendar

The brilliant star Sirius, appearing in the constellation we know as Canis Major, was ancient Egypt’s most important star. The Egyptians called the star Sopdet and equated it with Isis, the powerful goddess of regeneration.

The Greeks called the star Sothis, later developing a so-called Sothic calendar that kept even more regular track of the years and the seasons, being most nearly 365.25 days. Even then the calendar still wasn’t perfect.Incremental changes were occurring due to the rotation of the earth, the tilt of the earth, and the procession of the equinoxes.

The Civil Calendar

By divine decree laid down in the mists of prehistory, the Egyptian priest-king swore never to alter the civil calendar, even though its solar-basted calculations were not keeping up with the changing seasons. The reason for this seemingly irrational adherence lay in the fact that the year had been divinely established by the god of wisdom and time, Thoth.

Thoth’s laws were the laws of the gods, and divine laws were considered unalterable. The real reason may have been that astrologer priests were tracking an even larger arc of time – a procession not of the sun and moon, but of the equinoxes – that resulted in a kind of calendar of the ages.

When the Greeks arrived in Egypt, however, they saw little value in maintaining such a cosmic calendar when the civil calendar was so woefully out of alignment. Once they established themselves as kings, the Ptolemaic Greeks believed that the time had come to alter Thoth’s divine law. They coerced the priests into adding an extra day every four years to even out the true calendar. The result created the leap year, which we use even to this day.

How The Egyptian Calendar Works

At first Egypt’s calendar seems hard to understand because we are conditioned to our own notions of month and season derived from the Romans. Really, the ancient Egyptian calendar is fairly simple. The year has twelve months, the months have three weeks, and each week has ten days. This represented the basic system of the lunar year.

Tacked on to the end of these 360 days were the five Epagomenal Days, added to create the 365 days of the solar year. The Epagomenal Days signaled the end of the year and were followed by the new year’s celebration, just as New Year’s Day follows New Year’s Eve in our calendar. But, whereas we begin counting in the winter month of January, the ancient Egyptians began counting at the rise of the Dog Star Sirius, which occurs in the middle of our summer.

This system makes perfect sense because the new year signaled the beginning of a new agricultural cycle. When the Dog Star rose, the Nile flooded, and the parched earth was refertilized The sacred actions of the Nile River – its flooding, its retreat into its banks leaving fertile soil, and its eventual low flow creating drought conditions – determined not only the major festivals of the pharaoh and his people,but the three seasons of the year.

The Three Seasons

The ancient Egyptians did not celebrate four seasons of spring, summer, fall, and winter as we do. Rather, their three seasons were uniquely timed to the particular agricultural requirements in their geographic region. The three seasons were:

The ancient Egyptians did not celebrate four seasons of spring, summer, fall, and winter as we do. Rather, their three seasons were uniquely timed to the particular agricultural requirements in their geographic region. The three seasons were:

- Ahket – Innundation

Also called the Red Season, it extended from mid July to mid November, when most of the river valley and Delta were underwater.

- Pert – Sowing

Also called the Black Season, it extended from mid November to mid March, the equivalent to our spring, which the Egyptians called the Coming Forth.

- Shemu – Harvest

Also called the White Season, it extended from mid March to mid July when crops were harvested. By season’s end, everything was dry and the fields were scorched.

From: Feasts of Light

Krazelna: Day of Hekate

Krazelna: Day of Hekate

Krazelna: Day of Hekate

Rachel V Perry: Emancipation Day

Rachel: The Nemesia

Leave a Reply