Latin America

The Saci is one of the most well-known Brazilian legends – it even has its own national holiday. October 31 is Dia do Saci, or Saci Day. It was established to direct attention away from the American Halloween tradition and toward Brazilian culture but few Brazilians commemorate it, even with official support in São Paulo state and a few municipalities.

It is celebrated mainly among the youngest students, for whom Saci plays a magical and at the same time frightening role. Many teenagers still prefer Halloween with its pumpkins, costumes, and trick-or-treating.

Who is Saci?

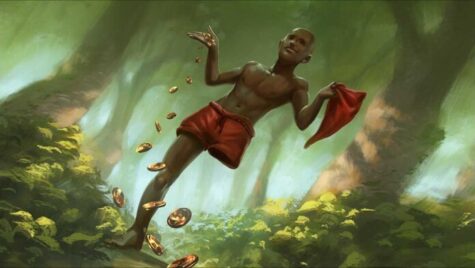

Saci (pronounced [saˈsi] or [sɐˈsi]) is a character in Brazilian folklore. In some regions, the Saci appears as an evil being, in others, as a playful and graceful creature. He is a one-legged black or bi-racial youngster, who smokes a pipe and wears a magical red cap that enables him to disappear and reappear wherever he wishes (usually in the middle of a dust devil).

Considered an annoying prankster in most parts of Brazil, and a potentially dangerous and malicious creature in others, he nevertheless grants wishes to anyone who manages to trap him or steal his magic cap. However, his cap is often depicted as having a bad smell. Most people who claimed to have stolen this cap say they can never wash the smell away.

Every dust devil, says the legend, is caused by the spin-dance of an invisible Saci. One can capture him by throwing into the dust devil a rosary made of separately blessed prayer beads, or by pouncing on it with a sieve. With care, the captured Saci can be coaxed to enter a dark glass bottle, where he can be imprisoned by a cork with a cross marked on it. He can also be enslaved by stealing his cap, which is the source of his power. However, depending on the treatment he gets from his master, an enslaved Saci who regains his freedom may become either a trustworthy guardian and friend, or a devious and terrible enemy.

Saci by Astrud Gilberto

Here’s a really song about Saci, by Astrud Gilberto with The James Last Orchestra. The lyrics (in English) follow the video.

English Lyrics for Saci:

In the middle of the night the rooster crowed three times

Many times it sang before the morning came

That’s when I saw that beauty

Of the washerwomen at the job of washing the clothes we wear

Often the cock

And I could not stop crying

alone behind the steering wheel that skidded

noticed a clear instant

What moite behind the Saci was crying

‘Inda could hear, do not know where

the song rolled in the air

There goes Pererê Saci jumping on his leg

To see the washerwomen in Chororó source

there comes Pererê Saci jumping on his leg

Deep deeper the woods

Cry, cry and no one has pity

There goes Pererê Saci jumping on his leg

To see the washerwomen in Chororó source

there comes the Pererê Saci jumping on his leg

Deep deeper the woods

Cry, cry and no one has pity

Here comes Saci, Here comes Saci, Here comes Saci Pererê

Ó Saci, ó Saci, ó Saci Pererê

There goes Pererê Saci jumping on his leg

To see the washerwomen in Chororó source

there comes the Pererê Saci jumping on the leg

Deep deeper the woods

Cry, cry and no one has pity

There goes Pererê Saci jumping on leg

To see the washerwomen in Chororó source

there comes the pererê saci jumping on the leg

Deep deeper the woods

Cry, cry and no one has pity

Here comes Saci, Here comes Saci, Here comes Saci Pererê

Here comes Saci, Here comes Saci, Here comes Saci Pererê

Sources:

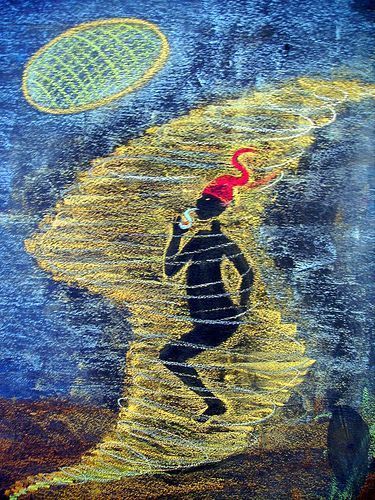

The Dance of the Devils (La danza de los diablos) is a dance performed in Costa Chica, the Pacific coast of Guerrero and Oaxaca in Mexico. As part of the ‘Day of the Dead’ festivities celebrated on the last days of October and the first days of November in Mexico. Its purpose is not so much to terrify however as to amuse and draw the community together while paying reverence to the spirits of the dead on the Day of the Dead.

Men dressed in rags and high boots perform the Dance of the Devils in Afro-Mexican communities. During these celebrations young men dress up as cowboys or as dead people, in which case they wear dusty clothes covered with terrain (to represent the passage of time and the fact of being buried underground). Their faces are covered with masks made of leather or paper with long beards and hair. A black beard represents a young devil, a white beard represents an old one. A small pair of goat or deer horns crowns the mask.

The men dance through different villages on All Souls Day, making noise and playing with children and young people by flogging them with a whip.

An elder diablo called el Terron, and a female diabla called la Minga, who carries a baby doll, lead the dancers. The elder diablo plays and whips the other diablos into dancing and chases la Minga around with the whip because she interrupts the concentration of the devil dancers. One way that la Minga attempts to disrupt the other dancers is by seduction, the Minga also tries to give her doll, which is a symbol of her productive power, to the dancers or to anyone in the audience, seeking a father to her ‘baby’.

The face of the men performing the dance is covered with a leather deer mask with horns and An elder devil, called Tenango, whips the other devils during this performance. Groups of 24 dancers (the devils) stomp and twirl in rows or circles along the streets; eventually, they stop at the houses where the owner gives them money or food for dancing.

Origins of the Dance of the Devils:

The Dance of the Devils is part of the ceremonial commemoration of the dead. It is a celebration of colonial origin, which was introduced by the black people of the Costa Chica of Guerrero and Oaxaca, who were brought there as slaves by the Spanish colonizers to work in mines, cotton plantations and cattle ranches.

From Río Grande, in the town of Tututepec, on the Oaxacan coast, to Tenango, in the municipality of Azoyú, to the north, this dance recalls the past times when ranchers or cowboys used the whip as well as trumpet to groups of wild cattle in order to force them to cross the Sierra Madre del Sur, to reach the plateau and sell the animals.

The Devils in the Mexican dance also use the whip, and behave according to the cowboy stereotype, that is, as brave and strong man. This performance, however, is also a historical memory, which becomes a ritual memory to the black population which was an intermediate caste, between the indigenous and the white land owners.

The black population who arrived in Mexico from very different lands such as Africa and the Antilles, bringing different languages and cultures, could not recreate a black culture of African traits, as could happen instead, to various degrees, in other Afro-American regions. These people therefore in their segregation from festivities and public celebrations organized by the masters of the haciendas, used to perform their own festivities secretly, by performing rituals to their African gods, playing drums and dancing.

At the same time, however, they borrowed elements of some indigenous and Catholic traditions and readopted them – with imagination and joy – to overcome the pain of domination and the humiliation of banishment.

It is no coincidence that the celebration of their ancestors is performed through the cowboy/devil figure. In this dance the ritual action harmonizes gestures and words. Devils are the dead who revive to do mischief, to steal, to sow fear and laughter. The dance could also be called the ‘Devil’s Game’, a game designed to laugh at the forbidden: a capataz (a boss), a bad mother, or a violent and bossy father.

The function of the Dance of the Devils, from a social aspect, is to cleanse and protect the community from spirits that carry evil energy. It can be viewed a way to control evil. In a sense, the dance is used to call the tono spirits of the ancestors to heal the community similar to the way an individual might be healed; the masks and the boite drum call the spirits and the dance is the mode of healing. Trance possession, another traditional healing mode, is also part of these dances, as a means to form a connection between the spiritual and material.

The dancers use their bodies to bring the spirits and form a bond between them and the community. “As they dance, they create an aura, which begins to rise and cover everyone who is sitting there. ” Even the children will come and sit quietly and watch. The force, she says, starts in the dancers’ hands and continues through their feet, legs, hips, shoulders, and faces until they are entirely transformed. The wearing of the tono masks allows them to achieve a more powerful transformation.

About The Dance:

The dance itself is strikingly similar to the egungun dances of West Africa; the performance is a form of ancestor reverence, and similar dances that may be seen throughout the Diaspora (the dispersion of the people from their original homeland). While the Dance of the Devils occurs within a context that includes European and Native influences, the core of the dance, its meaning and specific elements, are African.

The Dance of the Devils can be traced to Europe during the Middle Ages, but according to an Afro-Mestizo elder, the devils are spirits of the dead and not devils in search of souls. They are actually ancestral spirits whose presence is celebrated and encouraged. Similar to a dance performed by the Abakua in Cuba, dressing as a diablo (devil) symbolizes the willingness to allow the spirit to possess your body.

The egungun masquerades of West Africa are, like the Dance of the Devils, performed as part of a feast of the dead. Masks are worn which represent the dead, symbolically, but not as individual persons; flogging with whips is intended to promote growth and maturity in young men and fertility in women. The egungun dances were a strong social force in the societies where they originated, especially in times of unrest or external threat.

Another similarity is that while only men generally perform the dances, there is often at least one woman who either participates on some level or teaches the dance.

It has been suggested that the presence of the whip is a reference to the relationship between the former slaves and their overseers. However, the presence of flogging in the egungun dances of West Africa, when compared to Nana Minga and her baby, suggests that flogging is another African retention and bears its original symbolic meaning of fertility and protection against evil spiritual energy.

The dance being performed on the Day of the Dead leads one to think that the dance relates to the supernatural world of the spirits. The fact that the dancers dress in cowboy clothes and wear masks made of horse hair may be interpreted to mean that the dance represents the spirits of dead cowboys, the employment of many of the Afro-Mestizos cimarron ancestors. However, the masks, which appear animal-like, may in fact represent the tono spirits of ancestors, an idea supported by the presence of the boite drum.

The boite or bute, is a large gourd with a goatskin head; the drum is played by moving a stick through a hole in the center to create a vibration, not by striking. It is very similar to a drum used by the Abakua, an all-male secret society in Cuba, and is described in a similar fashion, as having the voice of a big cat, a leopard or jaguar, because of the roaring sound it makes.

When attempting to heal someone of sickness Afro-Mestizos call the animal tono of the sick person. Finding the person’s tono is a way to determine if the sickness is caused by the animal’s death. Healers in attempt to cure a person called the leopard, using the roaring sound of the boite drum to simulate the voice of the big cat.

Sources:

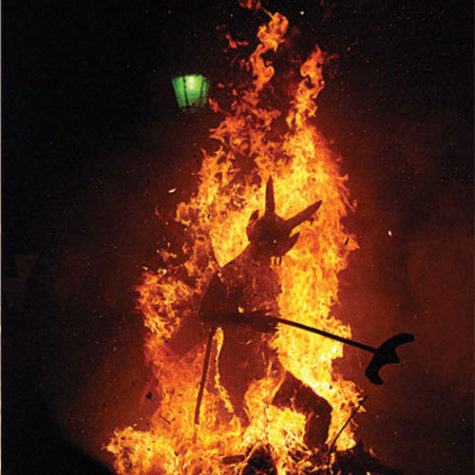

Burning the Devil or La Quema del Diablo is a tradition held every December 7, at 6:00 in the evening sharp, families build bonfires outside their homes and burn effigy of Satan. It is a tradition that many Guatemalans take part as a way to cleanse their home from devils that lurk in their home, creeping behind the furniture or hiding under the bed.

La quema del diablo can be traced to colonial time, a tradition that started since the 18th century. Held on the eve of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception and as a prelude to holiday season, those who could afford it adorns the fronts of their houses with lanterns, but for those who have lesser means builds a bonfires from their trash to celebrate the occasion.

A symbolical tradition with a belief that the fire burns the devil serves as purifying element, as the Virgin Mary was the blessed one to conceive baby Jesus must be free from any form of evil, therefore the event serves as “burning the devil” to clear the way for Mary’s feast.

Though the celebration may sound fun, it is controversial especially for the environmentalist groups. Back in the days, mostly paper were burned for the “cleansing ritual”, but now, piles of rubbish are mostly made of plastic and rubber that causes air pollution.

Over time the tradition evolved, from burning piles of garbage and pieces of furniture to being replaced by the effigy of Satan in a form of piñatas.

The tradition has special significance in Guatemala City because of its anticipation of Feast of the Immaculate Conception, the patron saint of the city. Along the street of Zona 1, the historic city center, many vendors pile the street selling stuffs associated with La Quema del Diablo, from firecrackers to simple and intricate devil piñatas. In different parts of the city, people celebrate and burn their own devil piñatas.

The tradition continues, as the idea is to burn all the bad from the previous year and to start anew from the ashes. It is widely observed throughout the country, The Devil is burned at the stroke of six. In Antigua, the former capital of the country, a devil three stories tall is constructed and burned in the city square.

A variation of this tradition is held in San Antonio Palopo. In this very unique celebration, they carry a statue of Maximón around town with a noose around his neck, they locals then hang Maximón by his neck in front of Catholic church, douse him with gasoline, and set him on fire. This is the local way of showing respect to the Christian god.

Setting people on fire has been a way of ridding the town of evil doers for many centuries. As soon as the Spaniards settled in Guatemala they brought with them the Christian religion. The Christian religion frowned on bloodshed. So instead they burned evil doers alive to kill them. This way they did not shed blood and therefor committed no sin.

Most of the inhabitants still pray to both the Christian and Mayan gods and deities such as Maximón or ancestors. They often ask for healing, wealth, help with love and sexual fertility.

The locals say they pray to both just in case one god does not grant their wishes the other might. This happens with both evangelical and Catholic believers. ( Not all, but the majority) This is kept secret for fear of discrimination from others.

While the many of the locals pray to both god and deities they publicly denounce Maximón shortly before Christmas by dragging him around the village then hang him with a noose and set him on fire.

The political version of this festival:

Guatemalans burn traditional devil puppets to start their Christmas celebrations. The ceremonial burning of devils started in the 16th century and is meant to chase away bad spirits. And in 2016, US president-elect Donald Trump was a big hit. But not in a good way.

Revelers in Guatemala set ablaze cardboard piñata of Trump wearing devil horns. In fact, piñata makers said Trump is far and away the best-seller. Trump’s hardline stance on immigration during his election campaign, including a promise to build a wall along the US-Mexico border, has drawn anger from Latin Americans in the US and around the world.

So this is a way to vent out the anger? It can be. Guatemalans believe the practice of torching the devil helps banish bad spirits from their homes and neighborhoods.

Sources:

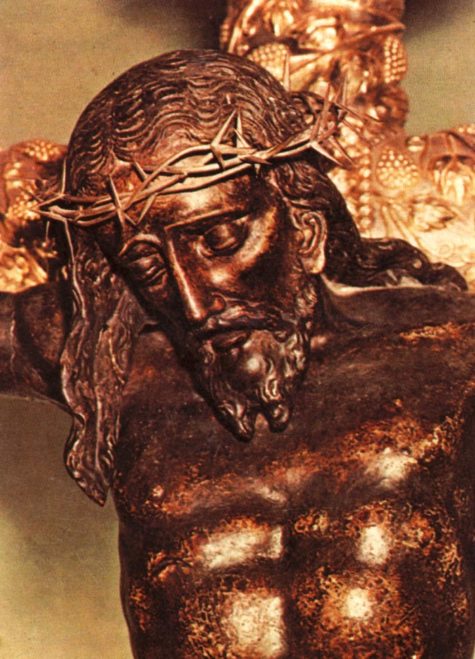

The Black Christ of Esquipulas is a wooden image of Christ now housed in the Cathedral Basilica of Esquipulas in Esquipulas, Guatemala. A lovely Baroque structure painted a gleaming white, the basilica dominates the town’s skyline. Remarkably, it has survived many earthquakes over the centuries with little damage.

The image is known as “black” because over more than 400 years of veneration its wood has acquired a darker hue, although such a name is relatively recent – in the 17th century it was also known as the “Miraculous Lord of Esquipulas” or the “Miraculous Crucifix venerated in the town called Esquipulas”.

The Black Christ is housed in a glass case on the altar at the east end of the basilica. A large statue that depicts Christ suffering on the cross, it is part of a Crucifixion group with Mary Magdalene and St. John.

Pilgrims stand in line along the west side of the church to see El Cristo Negro up close, sometimes waiting for over an hour. After viewing the statue and saying their prayers, pilgrims back away from it on the other side, believing it an offense to turn their back on the holy image.

Tens of thousands of devout Catholics cram into Esquipulas during the annual celebration of the Black Christ which happens on January 15th. They come to pray and ask for help in front of a religious icon which has been credited with miraculously curing Pedro Pardo de Figueroa, the Archbishop of Guatemala, from a serious illness in 1737.

The largest number of pilgrims come from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua and other Central American countries. The January 15th festival is also marked in the United States of America in cities such as Los Angeles, New Jersey and New York with a high Central American population.

Special processions and services are also held on July 21-27, and during Holy Week each year.

History of Esquipulas Basilica

The statue of the Black Christ (El Cristo Negro) was comissioned by Spanish conquistadors for a church in Esquipulas. It was carved in 1594 by Quirio Cataño in Antigua and installed in the church in 1595. By 1603, a miracle had already been attributed to the icon, and it attracted increasing numbers of pilgrims over the years.

The history of the Basilica begins in 1735, when a priest named Father Pedro Pardo de Figueroa experienced a miraculous cure after praying before the statue. When he became Archbishop of Guatemala, he commissioned a beautiful basilica to properly shelter the beloved statue. The church was completed in 1759.

Perhaps an even more impressive miracle is the fact that Esquipulas was the site of a Central American peace summit which laid the groundwork for what became the Guatemalan Peace Accords of 1996 which ended the country’s ghastly 36 year civil war.

The Basilica de Esquipulas is such a major religious site that Pope John Paul II paid a visit in 1996 to mark the 400th anniversary of the church which the Pope is said to have called “the spiritual center of Central America.” In 2009, celebrations were held to mark 250 years since the basilica’s construction.

Sources: Wikipedia, Sacred Destinations and Trans Americas

The pan de muerto (Spanish for Bread of the Dead or Day of the Dead Bread) is a type of bread from Mexico baked during the Dia de los Muertos season, around the end of October and the official holiday is celebrated on November 2. It is a soft bread shaped in round loaves with strips of dough attached on top (to resemble bones), and usually covered or sprinkled with sugar.

Another bread in the form of a sphere on the top represents a skull. The classic recipe for Pan de Muerto is a simple sweet bread recipe with the addition of anise seeds.

Pan de Muerto is sometimes baked with a toy skeleton inside. The one who finds the skeleton will have “good luck.” This bread is eaten during picnics at the graves along with tamales, cookies, and chocolate.

Ingredients:

- 1/4 cup milk

- 1/4 cup (half a stick) margarine or butter, cut into 8 pieces

- 1/4 cup sugar

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1 package active dry yeast

- 1/4 cup very warm water

- 2 eggs

- 3 cups all-purpose flour, unsifted

- 1/2 teaspoon anise seed

- 1/4 teaspoon ground cinnamon

- 2 teaspoons sugar

Instructions: Bring milk to boil and remove from heat. Stir in margarine or butter, 1/4 cup sugar and salt.

In large bowl, mix yeast with warm water until dissolved and let stand 5 minutes. Add the milk mixture.

Separate the yolk and white of one egg. Add the yolk to the yeast mixture, but save the white for later. Now add flour to the yeast and egg. Blend well until dough ball is formed.

Flour a pastry board or work surface very well and place the dough in center. Knead until smooth. Return to large bowl and cover with dish towel. Let rise in warm place for 90 minutes. Meanwhile, grease a baking sheet and preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

Knead dough again on floured surface. Now divide the dough into fourths and set one fourth aside. Roll the remaining 3 pieces into “ropes.”

On greased baking sheet, pinch 3 rope ends together and braid. Finish by pinching ends together on opposite side. Divide the remaining dough in half and form 2 “bones.” Cross and lay them atop braided loaf.

Cover bread with dish towel and let rise for 30 minutes. Meanwhile, in a bowl, mix anise seed, cinnamon and 2 teaspoons sugar together. In another bowl, beat egg white lightly.

When 30 minutes are up, brush top of bread with egg white and sprinkle with sugar mixture, except on cross bones. Bake at 350 degrees for 35 minutes.

Makes 8 to 10 servings.

Recipe found at: AzCentral

The Day of the Dead (El Día de los Muertos in Spanish) is a Mexican and Mexican-American celebration of deceased ancestors which occurs on November 1 and November 2, coinciding with the similar Roman Catholic celebrations of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day.

While it is primarily viewed as a Mexican holiday, it is also celebrated in communities in the United States with large populations of Mexican-Americans, and to a lesser extent elsewhere in Latin America.

Despite the morbid subject matter, this holiday is celebrated joyfully, and though it occurs at the same time as Halloween, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls’ Day, the mood of The Day of the Dead is much lighter, with the emphasis on celebrating and honoring the lives of the deceased, rather than fearing evil or malevolent spirits.

HISTORY OF DAY OF THE DEAD

The origins of the celebration of The Day of the Dead in Mexico can be traced back to the indigenous peoples of Latin America, such as the Aztecs, Mayans Purepecha, Nahua and Totonac.

Rituals celebrating the lives of dead ancestors had been performed by these Mesoamerican civilizations for at least 3,000 years. It was common practice to keep skulls as trophies and display them during rituals to symbolize death and rebirth.

The festival which was to become El Día de los Muertos fell on the ninth month of the Aztec Solar Calendar, near the start of August, and was celebrated for the entire month. Festivities were presided over by the goddess Mictecacihuatl, known as the “Lady of the Dead”. The festivities were dedicated to the celebration of children and the lives of dead relatives.

When the Spanish Conquistadors arrived in Central America in the 15th century they were appalled at the indigenous pagan practices, and in an attempt to convert the locals to Catholicism moved the popular festival to the beginning of November to coincide with the Catholic All Saints and All Souls days. All Saints’ Day is the day after Halloween, which was in turn based on the earlier pagan ritual of Samhain, the Celtic day and feast of the dead. The Spanish combined their custom of Halloween with the similar Mesoamerican festival, creating The Day of the Dead.

DAY OF THE DEAD TRIVIA

The souls of children are believed to return first on November 1, with adult spirits following on November 2.

Plans for the festival are made throughout the year, including gathering the goods that will be offered to the dead. During the period of October 31 and November 2 families usually clean and decorate the graves. Some wealthier families build altars in their homes, but most simply visit the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried and decorate their graves with ofrendas, or offerings. These include:

- wreaths of marigold, which are thought to attract the souls of the dead toward the offerings

- toys brought for dead children (los angelitos, or little angels)

- bottles of tequila, mezcal, pulque or atole for adults.

Ofrendas are also put in homes, usually with foods and beverages dedicated to the deceased, some people believe the spirits of the deceased eat the spirit of the food, so after the festivity, they eat the food from the ofrendas, but think it lacks nutritional value.

In some parts of Mexico, like Mixquic, people spend all night beside the graves of their relatives.

Those gifted, like to write “calaveras”, these are little poems that mock epitaphs of friends. Newspapers dedicate “Calaveras” to public figures, with cartoons of skeletons. Theatrical presentations of “Don Juan Tenorio” by José Zorrilla (1817-1893) are also traditional on this day.

A common symbol of the holiday is the skull, which celebrants represent in masks called calacas. Sugar skulls, inscribed with the names of the deceased on the forehead, are often eaten by a relative or friend. Other special foods for El Día de los Muertos includes Pan de Muertos (bread of the dead), a sweet egg bread made in many shapes, from plain rounds to skulls and rabbits.

Source: Wikipedia

Honoring the dead occurs in ancient cultures all over the world, and even in modern times it plays an important role in religions. It is founded on the belief that the dead live on and are able to influence the lives of later generations. These ancestors can assert their powers by blessing or cursing, and their worship is inspired by both respect and fear. Rituals consist of praying, presenting gifts, and making offerings. In some cultures, people try to get their ancestors’ advice through oracles before making important decisions.

Honoring the dead occurs in ancient cultures all over the world, and even in modern times it plays an important role in religions. It is founded on the belief that the dead live on and are able to influence the lives of later generations. These ancestors can assert their powers by blessing or cursing, and their worship is inspired by both respect and fear. Rituals consist of praying, presenting gifts, and making offerings. In some cultures, people try to get their ancestors’ advice through oracles before making important decisions.

The dead are believed by the peasantry of many Catholic countries to return to their former homes on All Souls’ Night and partake of the food of the living. In Tyrol, cakes are left for them on the table and the room kept warm for their comfort. In Brittany, people flock to the cemeteries at nightfall to kneel, bareheaded, at the graves of their loved ones, and to anoint the hollow of the tombstone with holy water or to pour libations of milk on it. At bedtime, the supper is left on the table for the souls. In Bolivia, many people believe that the dead eat the food that is left out for them. Some claim that the food is gone or partially consumed in the morning.

The Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexico and other countries can be traced back to the indigenous peoples such as the Olmec, Zapotec, Mixtec, Mexican, Aztec, Maya, P’urhépecha, and Totonac. Rituals celebrating the deaths of ancestors have been observed by these civilizations perhaps for as long as 2500–3000 years. In the pre-Hispanic era, it was common to keep skulls as trophies and display them during the rituals to symbolize death and rebirth.

The festival that became the modern Day of the Dead fell in the ninth month of the Aztec calendar, about the beginning of August, and was celebrated for an entire month. The festivities were dedicated to the goddess Mictecacihuatl, known as the “Lady of the Dead,” corresponding to the modern Catrina.

In most regions of Mexico, November 1st honors deceased children and infants where as deceased adults are honored on November 2nd. This is indicated by generally referring to November 1st mainly as “Día de los Inocentes” (Day of the Innocents) but also as “Día de los Angelitos” (Day of the Little Angels) and November 2nd as “Día de los Muertos” or “Día de los Difuntos” (Day of the Dead).

Many people believe that during the Day of the Dead, it is easier for the souls of the departed to visit the living. People will go to cemeteries to communicate with the souls of the departed, and will build private altars, containing the favorite foods and beverages, and photos and memorabilia, of the departed. The intent is to encourage visits by the souls, so that the souls will hear the prayers and the comments of the living directed to them. Celebrations can take a humorous tone, as celebrants remember funny events and anecdotes about the departed.

Plans for the festival are made throughout the year, including gathering the goods to be offered to the dead. During the period of November 1 and November 2, families usually clean and decorate graves; most visit the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried and decorate their graves with ofrendas, or offerings, which often include orange marigolds called “cempasúchitl.” In modern Mexico this name is often replaced with the term “Flor de Muerto” (“Flower of the Dead”). These flowers are thought to attract souls of the dead to the offerings.

Toys are brought for dead children (los angelitos, or little angels), and bottles of tequila, mezcal, pulque or atole for adults. Families will also offer trinkets or the deceased’s favorite candies on the grave. Ofrendas are also put in homes, usually with foods such as candied pumpkin, pan de muerto (“bread of the dead”) or sugar skulls and beverages such as atole. The ofrendas are left out in the homes as a welcoming gesture for the deceased. Some people believe the spirits of the dead eat the “spiritual essence” of the ofrenda food, so even though the celebrators eat the food after the festivities, they believe it lacks nutritional value. Pillows and blankets are left out so that the deceased can rest after their long journey. In some parts of Mexico, such as the towns of Mixquic, Pátzcuaro and Janitzio, people spend all night beside the graves of their relatives.

Some families build altars or small shrines in their homes. These altars usually have the Christian cross, statues or pictures of the Blessed Virgin Mary, pictures of deceased relatives and other persons, and scores of candles. Traditionally, families spend some time around the altar praying and telling anecdotes about the deceased. In some locations, celebrants wear shells on their clothing so when they dance the dead will wake up because of the noise. Some will dress up as the deceased.

Public schools at all levels build altars with offerings, usually omitting the religious symbols. Government offices usually have at least a small altar, as this holiday is seen as important to the Mexican heritage.

Those with writing talent sometimes create short poems, called “calaveras” (“skulls”), mocking epitaphs of friends, sometimes describing interesting habits and attitudes or some funny anecdotes. This custom originated in the 18th-19th century, after a newspaper published a poem narrating a dream of a cemetery in the future, “and all of us were dead”, proceeding to “read” the tombstones. Newspapers dedicate calaveras to public figures, with cartoons of skeletons in the style of José Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican illustrator. Theatrical presentations of Don Juan Tenorio by José Zorrilla (1817–1893) are also traditional on this day.

Island Pacanda, Lake Patzcuaro Mexico – Dia de los MuertosA common symbol of the holiday is the skull (colloquially called calavera), which celebrants represent in masks, called calacas (colloquial term for “skeleton”), and foods such as sugar skulls, which are inscribed with the name of the recipient on the forehead. Sugar skulls are gifts that can be given to both the living and the dead. Other holiday foods include pan de muerto, a sweet egg bread made in various shapes, from plain rounds to skulls and rabbits often decorated with white frosting to look like twisted bones.

José Guadalupe Posada created a famous print of a figure that he called “La Calavera de la Catrina” (“calavera of the female dandy”), as a parody of a Mexican upper class female. Posada’s striking image of a costumed female with a skeleton face has become associated with the Day of the Dead, and Catrina figures often are a prominent part of modern Day of the Dead observances.

The traditions and activities that take place in celebration of the Day of the Dead are not universal and often vary from town to town. For example, in the town of Pátzcuaro on the Lago de Pátzcuaro in Michoacán the tradition is very different if the deceased is a child rather than an adult. On November 1 of the year after a child’s death, the godparents set a table in the parents’ home with sweets, fruits, pan de muerto, a cross, a Rosary (used to ask the Virgin Mary to pray for them) and candles. This is meant to celebrate the child’s life, in respect and appreciation for the parents. There is also dancing with colorful costumes, often with skull-shaped masks and devil masks in the plaza or garden of the town. At midnight on November 2, the people light candles and ride winged boats called mariposas (Spanish for “butterfly”) to Janitzio, an island in the middle of the lake where there is a cemetery, to honor and celebrate the lives of the dead there.

In contrast, the town of Ocotepec, north of Cuernavaca in the State of Morelos opens its doors to visitors in exchange for ‘veladoras‘ (small wax candles) to show respect for the recently dead. In return, the visitors receive tamales and ‘atole‘. This is only done by the owners of the house where somebody in the household has died in the previous year. Many people of the surrounding areas arrive early to eat for free and enjoy the elaborate altars set up to receive the visitors from ‘Mictlán‘.

In some parts of the country, children in costumes roam the streets, asking passersby for a calaverita, a small gift of money; they don’t knock on people’s doors.

Some people believe that possessing “dia de los muertos” items can bring good luck. Many people get tattoos or have dolls of the dead to carry with them. They also clean their houses and prepare the favorite dishes of their deceased loved ones to place upon an altar.

Collected from various sources.

When former president Tabaré Vázquez created the ‘Día del nunca más’ (‘Never Again Day’) in 2006, he envisaged it drawing a line under the:

“horror of the recent past to salve the open wounds left by the dictatorship”

Ten years on and it is a safe bet that the ‘Never Again Day’ will in fact never be celebrated again.

I love the idea of a “Never Again Day.” It didn’t work for President Vázquez of Argentina, but maybe it could work on a personal level for those of us who need to take some time to make note of and work to change our most familiar patterns of self destruction.

The holiday of Cinco De Mayo, “The Fifth of May”, celebrates the victory of the Mexicans over the French army in 1862.

Shortly before the battle on May 5th Benito Juarez announced to his people:

The government of the republic will fulfill its duty to defend its independence, to repel foreign aggression, and accept the struggle to which it has been provoked, counting on the unanimous spirit of the Mexicans and on the fact that sooner or later the cause of rights and justice will triumph.

At the same time General Lorencz stated to the French government:

We are so superior to the Mexicans in race, in organization, in discipline, in morality, and in refinement of sensibilities, that as of this moment, at the head of our 6,000 valiant soldiers, I am the master of Mexico.

The battle lasted from daybreak to early evening, and when the French finally retreated they had lost nearly 500 soldiers. Fewer than 100 Mexicans had been killed in the clash.

And so it was that on May 5th the outnumbered, untrained, and ill-equipped Mexican people defeated the formidable French army. The success was unimaginable and was won with the determination and spirit of the Mexican people. However, victory was short lived and within a year France had successfully conquered Puebla and the rest of Mexico. They ruled there until 1867.

Cinco de Mayo celebrates the courage of the Mexican people during the battle on May 5th. It is often confused with the Mexican Independence Day, which occurred September 16, 1810 about 50 years earlier. A relatively minor holiday in Mexico, in the United States Cinco de Mayo has evolved into a commemoration of Mexican culture and heritage, particularly in areas with large Mexican-American populations.

Nifty Cinco de Mayo Party Ideas

- Send a Themed Invite –

Let everyone know right off the bat that this is a fun, festive fiesta by making sure your invitation reflects your theme. You might even want to send an online sign up to make it a potluck so people can share their favorite dishes.

- Create a Sombrero Centerpiece –

Set a sombrero on top of a tall vase or glass to give it height and fill the rim of the hat with fun, colorful treats.

- Spice It Up –

Fill the table with clear vases and margarita glasses that are filled with brightly colored yellow, red and green peppers.

- Get Colorful Silverware and Paper Products –

Think red cups, green forks and knives and white napkins — then you’ve got the colors of the Mexican flag covered!

- Reuse Containers –

Another alternative for an easy centerpiece is to buy canned Mexican food such as beans (put the food in an alternative container or cook it as part of your feast) and fill the cans with big, bright blooms.

- Make a Traditional Mexican Banner –

Papel picado (perforated paper) is a traditional Mexican folk art. It’s a decorative craft that involves cutting out intricate patterns on colorful tissue paper. Fold the tissue paper horizontally, then fold it over again. Use scissors to cut shapes in the paper. (It’s kind of like cutting paper snowflakes.) Once you have cut enough little patterns, unfold the paper.

- Red, White and … Green –

We’re all used to dressing in red, white and blue to celebrate July 4, why not get co-workers or party goers to dress in red, white and green for May 5? (The colors of the Mexican flag.)

- Create a Playlist of Mexican-themed Music –

You can go classic with authentic Mexican music or cue up some favorite Mexican-American artists like Carlos Santana and Selena.

- Hire a Mariachi Band –

Nothing gets people more in the mood to celebrate Mexican heritage than an actual, live Mariachi band. Everybody loves the serenade at the local Mexican dive restaurant, so if you really want to impress your guests, have a band come play in person.

Recipes and Food for Cinco de Mayo

- Flag Food –

Make a festive spread of your dips using salsa (red), queso blanco (white) and guacamole (green).

- Cinco de Mayo Fruit Cup –

With a squeeze of lime juice and a dusting of chili powder, slices of papaya, cantaloupe, mango, watermelon and pineapple take on a new depth of flavor perfect for this caliente holiday.

- Build Your Own Taco Bar –

Grab hard and soft shells and loads of toppings — think shredded cheese, meats, grilled veggies, Mexican rice, lettuce and more, and have guests build their own tacos. You could also do this with nachos.

- Cinco de Mayo Strawberries –

Easy and eye-catching, the kids can help you turn strawberries into the Mexican flag. Dip the red treats into melted white candy and top with green sprinkles. Enjoy!

- Piled High Nachos –

Grab your favorite bag of tortilla chips and spread evenly over a baking sheet. Add a mix of cheddar, Colby and Monterey Jack cheeses (shredded). Now add toppings of your choice. (That can mean ground beef, pork or chicken, black olives, tomatoes, corn, etc.) Bake at 400 degrees for five to 10 minutes (until warm). Then serve with sour cream, salsa or guacamole.

- DIY Pico De Gallo –

Take four chopped medium tomatoes, ¼ cup diced white onion, two seeded and minced jalapeno peppers, two tablespoons chopped green bell pepper, one clove minced garlic, ¼ cup chopped cilantro leaves, two tablespoons of fresh lime juice, a dash of salt and pepper and mix it all together. Refrigerate for an hour before serving.

- Mexican Rice Mashup –

This easy recipe will serve everyone at your party. Brown one pound of ground beef and combine with taco seasoning. Then in a cast iron skillet, sauté ½ tablespoon olive oil and ¼ cup of white onion diced. Add in four cups cooked rice, one cup black beans, one cup of corn, one cup of red peppers, one cup of green peppers, one diced tomato, and ½ cup of cilantro and mix with the ground beef. Then squeeze the juice from ½ of a lime over the dish.

- Watermelon Jicama Salad –

Slice half a watermelon into bite-size chunks. Combine that with one to two cups diced jicama, one mango (peeled and diced), one small bunch of chopped cilantro leaves, the juice of two limes, one teaspoon of salt, ¼ to ½ teaspoon black pepper and mix all the ingredients in a large serving bowl. Cover and refrigerate. Serve cold.

- Cheesy Enchilada Bake –

Brown one pound of ground turkey or beef and sauté with 1/3 cup of chopped white onions. Add a 15-ounce can of enchilada sauce. Separate the dough of a 16-ounce can of refrigerated biscuits into chunks and add to the meat. Put the mixture into a baking dish and top with 1½ cups of cheese. Bake at 350 degrees for 30 minutes. Garnish with green onions.

- Easy Quesadillas –

Place one large flour tortilla in a skillet with a little bit of oil, when it begins to brown add grated cheese (cheddar or Monterey Jack) and other ingredients. (You can add mushrooms, green onions, fresh tomatoes, avocado, lettuce and more.) Fold the tortilla in half, cook a little bit longer (until completely browned) and serve.

- Hot, Hot Mexican Zucchini –

Spray a large skillet with cooking spray, bring to medium heat. Add one garlic minced clove and heat until it sizzles. Add one pound of diced zucchini and cook until tender (about three minutes). Add one large diced tomato and one sliced green onion and cook for three more minutes. Remove skillet from heat, add one tablespoon fresh minced cilantro, jalapeno and fresh lime juice. Top with ½ cup feta cheese crumbles.

- Corn Salad –

Mix two 16-ounce frozen bags sweet corn (thawed), two large tomatoes (chopped), one Vidalia onion (chopped), ½ cup fresh cilantro (chopped), ¼ cup extra virgin olive oil, the juice of one lime, one 14-ounce can black beans (drained and rinsed) and a dash of salt and pepper. Once mixed well, let it stand and serve at room temperature.

- Mango and Avocado Salsa –

Combine one mango and one avocado (peeled, pitted and diced), four medium tomatoes, one jalapeno pepper (seeded and diced), ½ cup chopped fresh cilantro, three cloves minced garlic, one teaspoon salt, two tablespoons fresh lime juice, ¼ cup red onion (chopped) and three tablespoons olive oil in a medium bowl and stir well. Refrigerate before serving with chips.

- Easy Guacamole –

In a medium bowl mash together three avocadoes, the juice of one lime, and one teaspoon of salt. Mix in ½ cup of a diced onion, three tablespoons chopped fresh cilantro, two tomatoes and one teaspoon of minced garlic. Stir in cayenne pepper. Refrigerate for one hour or serve immediately with chips.

- Mexican Wedding Cookies –

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Beat one cup butter (softened), ½ cup powdered sugar and one teaspoon vanilla. Then add two cups flour and one cup chopped pecans. Bake 14 to 15 minutes or until bottoms are lightly browned. Cool five minutes on baking sheets. Roll warm cookies, one at a time, in ½ cup powdered sugar in small bowl until evenly coated.

- Mexican Pineapple Water –

Also known as Agua de Piña, this drink is simple to make. Cut one skinned and cored pineapple into chunks and combine in a blender with two cups of water. Once blended, add two more cups of water and run through a mesh sieve. Add more water and one to two cups of sugar until you reach your desired sweetness and consistency.

- Watermelon Lemonade –

This drink is easy and fun and should fit easily with your party vibe. Mix two cups of watermelon juice (from an actual watermelon) with four cups of lemonade.

- Frozen Watermelon Lemonade –

Create with or without alcohol. Once you have your two juices mixed, pour the half of each juice into ice cube trays and freeze. Take frozen cubes and simply mix with liquids in a blender.

- Strawberry Margarita Punch –

Mix 15 ounces of frozen strawberries, 24 ounces of lemon lime soda and 12 ounces of frozen limeade in a blender, then pour in two cups of orange juice and stir. This cocktail is super refreshing, delicious and literally made in minutes. You can make this with or without tequila.

- Candy Buffet –

Send guests home with a colorful sweet treat in the flag colors. Use Twizzlers or red hots, white chocolate Hershey kisses, green licorice and red and green M&Ms. Set out small bags to scoop the candy into and take home with them.

- Hire a Mexican-themed Food Truck –

Leave the cooking to someone else while your guests enjoy the fun of the food truck!

Games and Activities for Cinco de Mayo

- Scavenger Hunt –

Have guests search for items like a small bag of tortilla chips, a bottle of hot sauce, a sombrero, a mini Mexican flag and more. Make sure the winner gets a fun prize. (Maybe everything they just found!)

- How Hot Is It? –

Arrange chili peppers (or sauces) with different heat levels on a table. Keep track of how hot everything is. Have a few brave souls try them and the rest of the crowd guess how hot they are based on the reactions.

- DIY Piñata –

Use a decorative shopping bag and fill it with candy (and some crinkled up newspaper to fill some space), then tape or staple the shopping bag closed and hang it just high enough so that it’s hard to hit. Blindfold your guests and watch them take a whack at your colorful creation! This works for kids and adults. You can get creative with how you fill the piñata if it’s for kids.

- Pass the Sombrero –

Much like musical chairs, guests pass the hat and when the music stops, the person holding the hat is out. Make things more entertaining by giving contestants the option to do a Mexican hat dance for a chance to get back in the game.

- Mustache Selfie Contest –

Buy packs of different kinds of stick-on mustaches and have guests take fun selfies wearing them. Then decide as a group who took the best photo.

- Nacho Eating Contest –

Blindfold contestants and offer them chips-and-messy-dip and see who can finish the bowl first.

- DIY Maracas –

Get two mini paper cups. Paint and decorate the outside of each one. Then fill one cup halfway with dried pinto beans. Apply hot glue to the top edge of the cup and place the second cup on the glue to create the maraca. Then shake!

- Giant Tissue Paper Flowers Craft –

Cut out circles or squares of different colored tissue paper. Give guests two to three pieces and place them on top of each other. Carefully pinch the layers in the center and secure with a twist tie. Then open out the different layers to reveal a multicolored flower.

- Terra Cotta Pot Decoration –

Have guests use acrylic paint to decorate terra cotta pots with popular Mexican-themed symbols like the flag, the sun, a cactus, sombreros and more.

- Traditional Dancing –

Get your guests shaking more than just their maracas! Bring in a trained professional to teach the group how to samba, salsa, rumba and more.

- Sing It –

If your guests are into performing, rent a karaoke machine and use your playlist as the song choices for some good old-fashioned living room karaoke.

Kid Stuff For Cinco de Mayo

- Make Your Own Poncho –

Lay a paper grocery bag flat on the table. Cut around the outside of it, snipping off the folds. Cut the neck hole by layering the two sections together. Test it on your child’s head to make sure it’s big enough. Staple the area where the two bags meet at the shoulder. Then decorate with bright colored crayons or markers.

- Play the Mexican Lottery (Bingo) –

The Lotería game set includes a deck of 54 cards with colorful images and 10 boards, with a random pattern of 16 images. It’s very similar to American bingo and you can find a Lotería set online.

- Play Ball –

Kickball is a traditional game played in Mexican villages (though it’s a bit different than American kickball) and is great for an outdoor party. Divide partygoers into two teams. The aim of the game is for each team member to kick a ball around an obstacle course and the first team where every member completes the course wins. You can use cones, chairs — anything — to create the obstacle course.

- Mexican Train Domino Game –

Play a game of dominoes where the object is to create a “train” (chain) using all the dominoes in your hand. (You can use a traditional set of dominoes for this version of the game but you will also need to make a “hub” with slots for each players train. You can cut this out of cardboard or buy a fancier set online.

- Speak the Language –

You and your guests can learn some key Spanish phrases from an español-speaking friend to appreciate the culture behind the holiday. (Hola!)

- Make a Word Search –

Use the phrases you just learned to create a custom word search for the kids at your party.

- Play Marbles –

Marbles are still hugely popular in Mexico. Get a variety of marbles in different sizes and colors and let kids play this classic game.

- Pin the Tail on the Donkey –

We’ve all played this game — as kids and adults! Considering the donkey is considered a beloved “hero” in Mexico, it seems like a good day to dig out the classic.

- Play Soccer (Fútbol) –

This popular Mexican sport will help kids burn off some energy. Set up two cones (to form a “goal”) on either side of your backyard and host a friendly game of fútbol. Go the extra mile and have T-shirts made to distinguish the teams.

Sources:

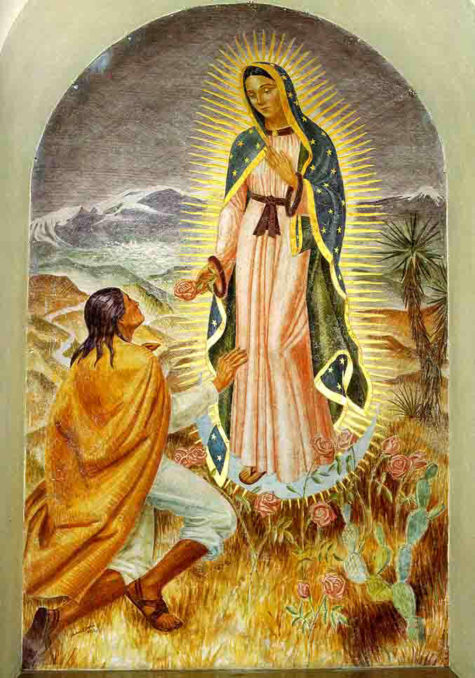

December 12th is the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, patroness of the Americas, unborn children, and the New Evangelization. The day is particularly special for Americans of Mexican heritage, as it honors the belief that Jesus’ mother Mary, who is Mexico’s patron saint, appeared to a man in Mexico City twice in 1531.

Our Lady of Guadalupe is unlike any other apparition of the Virgin Mary. First, it is the only apparition where Our Lady left a miraculous image of herself unmade by human hands. Second, it is the only universally venerated Madonna and Child image where Our Lady appears pregnant instead of holding the Infant Jesus.

Feast Day Celebration Ideas:

Many parishes with large Hispanic populations have a special celebration leading up to the December 12th feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Find one of these celebrations happening in your local community and join in the celebration. Some parishes will also host a reception or party in honor of the feast day.

If not, hold your own celebration of Our Lady by inviting friends and family to your home for a traditional Mexican meal. Decorate your table with colorful flowers in bright reds and pinks, blues and greens, and together recite the prayer (below) to Our Lady written by Pope St. John Paul II.

Prayer To Our Lady of Guadalupe:

“O Immaculate Virgin, Mother of the true God and Mother of the Church!, who from this place reveal your clemency and your pity to all those who ask for your protection, hear the prayer that we address to you with filial trust, and present it to your Son Jesus, our sole Redeemer.

Mother of Mercy, Teacher of hidden and silent sacrifice, to you, who come to meet us sinners, we dedicate on this day all our being and all our love. We also dedicate to you our life, our work, our joys, our infirmities and our sorrows. Grant peace, justice and prosperity to our peoples; for we entrust to your care all that we have and all that we are, our Lady and Mother. We wish to be entirely yours and to walk with you along the way of complete faithfulness to Jesus Christ in His Church; hold us always with your loving hand.

Virgin of Guadalupe, Mother of the Americas, we pray to you for all the Bishops, that they may lead the faithful along paths of intense Christian life, of love and humble service of God and souls. Contemplate this immense harvest, and intercede with the Lord that He may instill a hunger for holiness in the whole people of God, and grant abundant vocations of priests and religious, strong in the faith and zealous dispensers of God’s mysteries.

Grant to our homes the grace of loving and respecting life in its beginnings, with the same love with which you conceived in your womb the life of the Son of God. Blessed Virgin Mary, protect our families, so that they may always be united, and bless the upbringing of our children.

Our hope, look upon us with compassion, teach us to go continually to Jesus and, if we fall, help us to rise again, to return to Him, by means of the confession of our faults and sins in the Sacrament of Penance, which gives peace to the soul.

We beg you to grant us a great love for all the holy Sacraments, which are, as it were, the signs that your Son left us on earth.

Thus, Most Holy Mother, with the peace of God in our conscience, with our hearts free from evil and hatred, we will be able to bring to all true joy and true peace, which come to us from your son, our Lord Jesus Christ, who with God the Father and the Holy Spirit, lives and reigns for ever and ever. Amen.”

~Pope John Paul II’s Prayer to Our Lady of Guadalupe

~Mexico, January 1979