Ghosts

The Feralia was the closing festival of the ancient Roman festival of Parentalia. During the Feralia, families would picnic at the tombs of their deceased family members and give libations to the dearly departed. It was believed that the shades of the dead could walk upon the earth above their graves during Feralia.

Roman citizens were instructed to bring offerings to the tombs of their dead ancestors which consisted of at least “an arrangement of wreaths, a sprinkling of grain and a bit of salt, bread soaked in wine and violets scattered about.” Additional offerings were permitted, however the dead were appeased with just the aforementioned.

Ovid tells of a time when Romans, in the midst of war, neglected Feralia, which prompted the spirits of the departed to rise from their graves in anger, howling and roaming the streets. After this event, tribute to the tombs were then made and the ghastly hauntings ceased.

“And the grave must be honoured. Appease your fathers’ Spirits, and bring little gifts to the tombs you built. Their shades ask little, piety they prefer to costly offerings: no greedy deities haunt the Stygian depths. A tile wreathed round with garlands offered is enough, A scattering of meal, and a few grains of salt, and bread soaked in wine, and loose violets: Set them on a brick left in the middle of the path…

…and hide the gods, closing those revealing temple doors, Let the altars be free of incense, the hearths without fire. Now ghostly spirits and the entombed dead wander, Now the shadow feeds on the nourishment that’s offered. But it only lasts till there are no more days in the month Than the feet that my metres possess. This day they call the Feralia because they bear [ferunt] Offerings to the dead: the last day to propitiate the shades.” – Ovid

To indicate public mourning, marriages of any kind were prohibited on the Feralia, and Ovid urged mothers, brides, and widows to refrain from lighting their wedding torches. Magistrates stopped wearing their insignia and any worship of the gods was prohibited as it “should be hidden behind closed temple doors; no incense on the altar, no fire on the hearth.”

In Italy, the sine qua non of All Souls’ celebrations is a cookie called “Ossi di Morto,” or “Bones of the Dead.”

Here’s a recipe:

- 1 1/4 cups flour

- 10 oz almonds

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 1 oz pine nuts

- 1 TBSP butter

- A shot glass full of brandy or grappa

- The grated zest of half a lemon

- Cinnamon

- One egg and one egg white, lightly beaten

Blanch the almonds, peel them, and chop them finely (you can do this in a blender, but be careful not to over-chop and liquefy).

Combine all the ingredients except the egg in a bowl, mixing them with a spoon until you have a firm dough. Dust your hands and work surface with flour, and roll the dough out between your palms to make a “snake” about a half inch thick. Cut it into two-inch long pieces on the diagonal. Put on greased and floured cookie sheet, brush with the beaten egg, and bake them in a 330-350 oven for about 20 minutes. Serve them cold. Because they are a dry, hard cookie, it is good to serve these with something to drink.

There is a Mexican saying that we die three deaths: the first when our bodies die, the second when our bodies are lowered into the earth out of sight, and the third when our loved ones forget us.

Some believe that the origins of All Souls’ Day in European folklore and folk belief are related to customs of ancestor veneration practiced worldwide. It is practically universal folk belief that the souls of the dead (or those in Purgatory) are allowed to return to earth on All Souls Day. In Austria, they are said to wander the forests, praying for release. In Poland, they are said to visit their parish churches at midnight, where a light can be seen because of their presence. Afterward, they visit their families, and to make them welcome, a door or window is left open. In many places, a place is set for the dead at supper, or food is otherwise left out for them.

In any case, our beloved dead should be remembered, commemorated, and prayed for.

During our visits to their graves, we spruce up their resting sites, sprinkling them with holy water, leaving votive candles, and adorning them flowers (especially chrysanthemums and marigolds) to symbolize the Eden-like paradise that man was created to enjoy, and may, if saved, enjoy after death and any needed purgation.

Today is a good day to not only remember the dead spiritually, but to tell your children about their ancestors. Bring out those old photo albums and family trees! Write down your family’s stories for your children and grandchildren! Impress upon them the importance of their ancestors!

Traditional foods:

Around the world:

The formal commemoration of the saints and martyrs (All Saints’ Day) existed in the early Christian church since its legalization, and alongside that developed a day for commemoration of all the dead (All Souls’ Day). The modern date of All Souls’ Day was first popularized in the early eleventh century after Abbot Odilo established it as a day for the monks of Cluny and associated monasteries to pray for the souls in purgatory.

Many of these European traditions reflect the dogma of purgatory. For example, ringing bells for the dead was believed to comfort them in their cleansing there, while the sharing of soul cakes with the poor helped to buy the dead a bit of respite from the suffering of purgatory. In the same way, lighting candles was meant to kindle a light for the dead souls languishing in the darkness. Out of this grew the traditions of “going souling” and the baking of special types of bread or cakes.

In Tirol, cakes are left for them on the table and the room kept warm for their comfort. In Brittany, people flock to the cemeteries at nightfall to kneel, bareheaded, at the graves of their loved ones, and to anoint the hollow of the tombstone with holy water or to pour libations of milk on it. At bedtime, the supper is left on the table for the souls.

In Bolivia, many people believe that the dead eat the food that is left out for them. In Brazil people attend a Mass or visit the cemetery taking flowers to decorate their relatives’ grave, but no food is involved.

In Malta many people make pilgrimages to graveyards, not just to visit the graves of their dead relatives, but to experience the special day in all its significance. Visits are not restricted to this day alone. During the month of November, Malta’s cemeteries are frequented by families of the departed. Mass is also said throughout the month, with certain Catholic parishes organizing special events at cemetery chapels.

In Linz, funereal musical pieces known as aequales were played from tower tops on All Soul’s Day and the evening before.

In Mexico “Dia de Los Muertos” (Day of the Dead) is celebrated very joyfully — and colorfully. A special altar, called an ofrenda, is made just for these days of the dead (1 and 2 November). It has at least three tiers, and is covered with pictures of Saints, pictures of and personal items belonging to dead loved ones, skulls, pictures of cavorting skeletons (calaveras), marigolds, water, salt, bread, and a candle for each of their dead (plus one extra so no one is left out).

A special bread is baked just for this day, Pan de Muerto, which is sometimes baked with a toy skeleton inside. The one who finds the skeleton will have “good luck.” This bread is eaten during picnics at the graves along with tamales, cookies, and chocolate. They also make brightly-colored skulls out of sugar to place on the family altars and give to children.

Collected from various sources

The seventh lunar month in the traditional Chinese calendar is called Ghost Month. These dates vary from year to year, in 2017, Ghost Month runs from August 28 to September 19, and the Ghost Festival is on Sept 5.

On the first day of the month, the Gates of Hell are sprung open to allow ghosts and spirits access to the world of the living. The spirits spend the month visiting their families, feasting and and looking for victims.

There are many taboos in the Ghost Month. For example, do not wear the clothes with your name, do not pat other people on the shoulder, do not whistle, children and senior citizens should not go out at night.

There are three important days during Ghost Month. On the first day of the month, ancestors are honored with offerings of food, incense, and ghost money – paper money which is burned so the spirits can use it. These offerings are done at makeshift altars set up on sidewalks outside the house.

Almost as important as honoring your ancestors, offerings to ghosts without families must be made, so that they will not cause you any harm. Ghost month is the most dangerous time of the year, and malevolent spirits are on the look out to capture souls.

This makes ghost month a bad time to do activities such as evening strolls, traveling, moving house, or starting a new business. Many people avoid swimming during ghost month, since there are many spirits in the water which can try to drown you.

The 15th day of the month is Ghost Festival, sometimes called Hungry Ghost Festival. The Mandarin name of this festival is zhōng yuán jié (中元節 / 中元节). This is the day when the spirits are in high gear. It’s important to give them a sumptuous feast, to please them and to bring luck to the family. Taoists and Buddhists perform ceremonies on this day to ease the sufferings of the deceased.

The last day of the month is when the Gates of Hell are closed up again. The chants of Taoist priests inform the spirits that it’s time to return, and as they are confined once again to the underworld, they let out an unearthly wail of lament.

The story:

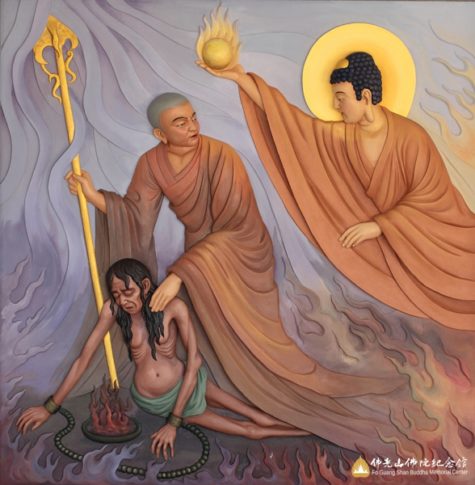

The idea of a feast for the ghosts comes from a story of Buddhism. Moggallana was one of Buddha Shakyamuni’s best students. He had various supernormal powers and owned the divine eyes. One day, he saw his deceased mother had been born among hungry ghosts.

He went down the Hell, filled a bowl with food to provide for his mother. Before reaching his mother’s month, the food turned into burning coals which couldn’t be eaten. Moggallana cried sorrowfully and asked for help from Buddha.

Buddha said the sins of his mother were deep and firmly rooted, and couldn’t be forgiven just using the divine power. It would require the combined power of thousand monks to get rid of her sins. Buddha told Moggallana:

“the 15th day of the 7th lunar month is the Pavarana Day for the assembled monks of all directions. You should prepare an offering of clean basins full of hundreds of flavors and the five fruits, and other offerings of incense, oil, lamp, candle… to the greatly virtuous assembled monks. Your present parents and parents of seven generations will escape from sufferings.”

Following Buddha’s instructions, Moggallana’s mother obtained liberation from sufferings as a hungry ghost by receiving the power of the merit and virtue form the awesome spiritual power of assembled monks on 15th day of the 7th lunar month.

Today, similar rituals are held in the Buddhism temples on this day for the deliverance of all suffering spirits.

Found at: Mandarin.About.Com and other sources

According to Japanese Buddhist belief, every summer at this time spirits of the dead return to visit their families. O-Bon is a Buddhist ceremony for welcoming back and appeasing the souls of our ancestors.

During the course of this festival, the souls of the dead are guided home, feted for several days, and then sent back to the spirit world.

The formal name of this festival is Ura-Bon, and generally falls on Aug 13 thru Aug 15. Depending on the region, however, the Bon Festival may be held one month earlier, or July 13th-15th.

The word O-Bon has its roots in the Sanskrit word ullambana, which means ‘deliverance from suffering’. The festival combines early Buddhist rituals designed to rescue the souls of the dead from hell, with native Japanese agricultural rites and the Shinto tradition of welcoming back the souls of ancestors in late summer.

Traditionally, the bones of the deceased are placed in individual urns and kept with their ancestors in a family tomb (ohaka). For several consecutive evenings during the week of O-Bon, paper lanterns painted with the family crest are hung to guide the ancestral spirits to the ohaka.

Alternatively, small welcoming fires (mukaebi) may be lit at the entrance to the home, or in front of the gate early on the evening of the 13th to receive the souls of the ancestors.

It is also customary at this time to clean the family grave and present fresh flowers and incense. Those who are unable to travel to their family burial place may instead spruce up the domestic altar. Houses are cleaned and decorated and a place is sometimes set at the family table for the recently departed.

Although many Japanese also hold Shinto beliefs, it is Buddhism that is associated with rituals concerned with death. Therefore it is the Buddhist household altar — the butsudan — that remains the focus of attention during O-Bon.

Offering stands and a small tray with tiny dishes for the symbolic meals offered to the ancestors are brought out, and a special shelf (Shoryodana or ‘Shelf of Souls’) is set up in front of the altar; it is here that, for the duration of O-Bon, the spirits are believed to dwell.

At the end of three days (on the 16th), the lanterns are again set out to guide the spirits back, and an okuribi (farewell) fire is lit to see off the souls of the ancestors.

Collected from various sources including Mythic Maps

The Lemuria, the festival in honor of the Lemures, the spirits of dead family members who wander the earth on these three spring nights (May 9, 11, and 13).

The Lemuria is held on odd-numbered days because even-numbered days are considered unlucky. It is a festival designed to honor the Lemures, they are regarded as baleful spirits of the dead who died violent or otherwise untimely deaths.

At midnight, the Paterfamilias (head of the household) arises and dresses with no knots, buckles, or other constricting items on his person (thus he is barefoot). He makes the sign of the mano fico with his hands (a fist with the thumb placed between the index and middle fingers; a sign of good luck and fertility) and then washes his hands in pure water. He then walks through the house, spitting out nine black beans, being careful not to look behind him as the lemures accept the beans as a sort of ransom for the living members of the household. As he spits out each one, he says

“With these beans I redeem me and mine.”

Once all nine beans have been accepted by the lemures and the entire house walked through, the Paterfamilias then washes his hands again, clashes two vessels of bronze together, and nine times says

“Ghosts of my fathers, be gone.”

(Manes exite paternae.)

Source: Novaroma

For modern Wiccans and Neo-Pagans, Nov 16 is designated as Hekate Night, or the Night of the Crossroads, the day of the festival of Hecate Trivia, which is a day that honors Hecate as a goddess of crossroads.

Her feast day begins at sunset, and most often consists of a feast referred to as Hekate Supper, A meal to which Hekate is invited, and given her own plate of food, which is then left at a crossroads.

This practice, particularly associated with the sacred three-way crossroads of Hekate, is the depina Hekates, or Hekate Supper. It may be that these offerings were made to appease ghosts and keep them at the crossroads, avoiding trouble from them whilst traveling etc. Alternatively these offerings were described as being made to placate the goddess and ensure that she would look favorably upon those who made regular offerings.

- More about Hekate Suppers here: Night of Hekate Suppers

- Invocations and prayers to Hekate: Widdershins

- Spells and Magick: Book of Shadows

- About the Goddess: The Powers That Be

It has been suggested that the crossroads was sacred to Hekate due to her having been abandoned at a crossroads as a baby by her mother Pheraea, and then rescued and brought up by shepherds. This Thessalian tale comes from a scholiast to Lycophron’s 3rd century BCE play Alexandria, and was a late invention.

Aristophanes recorded that offerings to Hekate were made “on the eve of the new moon” which is when the first sliver of the new moon is visible, signifying a possible connection with Hekate as a lunar goddess, rising, like the moon, from the underworld on the night of the new moon.

There are also references to the offerings being made on the thirtieth day of the month, but keep in mind that this was calculated on the Greek calendars, it would vary from state to state as there was no uniformity in the calendar system being used.

It has further been suggested that the offerings made at the Hekate Suppers were a form of charity, and certainly the consumption of the food by the poor was noted by Aristophanes (5th century satirist):

“Ask Hekate whether it is better to be rich or starving; she will tell you that the rich send her a meal every month and that the poor make it disappear before it is even served.”

The 10th century Byzantine encyclopedia, the Suda, paraphrased this quote and added the following:

“From her one may learn whether it is better to be rich or to go hungry. For she says that those who have and who are wealthy should send her a dinner each month, but that the poor among mankind should snatch it before they put it down. For it was customary for the rich to offer loaves and other things to Hekate each month, and for the poor to take from them.”

Various sources mention different foods offered to Hekate at the suppers. These were:

- Magides – A type of loaf or cake

- Mainis – Sprat

- Skoroda – Garlic

- Tigle – Mullet

- Psammeta – Sacrificial cake somewhat like the psaista

- Oon – Eggs (raw)

- Tyros – Cheese

- Basunias – A type of cake

Another type of food offering which was left to Hekate on the eve of the full moon was the amphiphon, a type of cake. Amphiphon means “light-about,” an appropriate name for this flat cheesecake which was surrounded by small torches.

The supper, or leaving of offerings at the crossroads was one of the hardest practices for the Christian church to stamp out. Records indicate it was still taking place in the 11th century CE, and it may well have continued far longer.

About Hekate

She is the Triple Goddess, and most often associated with a three-way crossroad. She is Hecate the Maiden, Hecate the Mother, and Hecate the Crone. Although the dark of the moon is her traditional time, Hecate can be called upon during any moon phase, as She is the One and the Three.

She is the goddess of witchcraft, the night, the new moon, ghosts, necromancy and crossroads. Hekate had few public temples in the ancient world, however, small household shrines, which were erected to ward off evil and the malevolent powers of witchcraft, were quite common.

She is a Goddess like no other. A goddess who is not to be invoked lightly, or by those who are calling upon her frivolously. Some describe her as a Witch Goddess who rises up from the dark depths of the underworld, whilst others tell of a bright shining Goddess who holds her torches of illumination high, revealing the path through the mysteries, but only for those with the wisdom to follow her.

Some say that she is the Axis Mundi, the Chaldean World Soul and that she brings soul fire and light to humanity. Others tell of a powerful Goddess who is crowned with the coils of wild serpents and oak leaves, appearing with three heads, often with three bodies, sometimes in forms which are part-human and part-beast. We are told that she holds sway in many worlds, bearing the keys to the thresholds between, guarding and blessing those who make suitable offerings to her, but feared by those who let injustice come upon the world.

Hekate stands at the crossroads bearing the keys to the mysteries. In the ancient world she inspired poets and philosophers, witches, magicians and ordinary people, all of whom knew she could bestow blessings to improve their lot and protect them from the harsh denizens of the infernal realm. Today she continues to inspire and evoke awe in those who encounter her; for some in subtle ways, leading them in an elusive nameless manner with her symbols, for others in a more powerful and directly empowering way.

Sources:

Although it’s customary in many traditions to spend time at the grave site, cleaning, caring, and sometimes bringing offerings of food and drink, particularly during Day of the Dead celebrations, (or any of other days specifically set aside to honor the dead), a more direct method was used in ancient Greece.

Create a blend of olive oil, honey, and spring water. This may be poured directly onto the grave, or poured through a tube into the grave. Meanwhile the living should picnic nearby while sharing remembrances of the deceased.

Halloween or All Hallow’s Eve occurs on October 31, and originated with the ancient Celts, who, beginning at sundown on October 31 and extending into November 1, celebrated Samhain (pronounced sow-in, which rhymes with cow-in), which marked the end of harvest time and the beginning of the new year. The ancient Celts believed that at this time, the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead was at its thinnest, thereby making it a good time to communicate with the deceased and to divine the future.

In later years, the Irish used hollowed-out, candlelit turnips, carved with a demon’s face to frighten away the spirits. When Irish immigrants in the 1840s found few turnips in the United States, they used the more plentiful pumpkins instead.

Halloween activities include:

- Trick-or-treating (going door to door in costume and asking for treats)

- Attending Halloween costume parties

- Decorating, carving pumpkins into jack-o’-lanterns

- Lighting bonfires

- Apple bobbing

- Divination games

- Playing pranks

- Visiting haunted attractions

- Telling scary stories and watching horror films.

In many parts of the world, the Christian religious observances of All Hallows’ Eve, including attending church services and lighting candles on the graves of the dead, remain popular, although elsewhere it is a more commercial and secular celebration. Some Christians historically abstained from meat on All Hallows’ Eve, a tradition reflected in the eating of certain foods on this vigil day, including apples, potato pancakes and soul cakes.

Related Content:

Honoring the dead occurs in ancient cultures all over the world, and even in modern times it plays an important role in religions. It is founded on the belief that the dead live on and are able to influence the lives of later generations. These ancestors can assert their powers by blessing or cursing, and their worship is inspired by both respect and fear. Rituals consist of praying, presenting gifts, and making offerings. In some cultures, people try to get their ancestors’ advice through oracles before making important decisions.

Honoring the dead occurs in ancient cultures all over the world, and even in modern times it plays an important role in religions. It is founded on the belief that the dead live on and are able to influence the lives of later generations. These ancestors can assert their powers by blessing or cursing, and their worship is inspired by both respect and fear. Rituals consist of praying, presenting gifts, and making offerings. In some cultures, people try to get their ancestors’ advice through oracles before making important decisions.

The dead are believed by the peasantry of many Catholic countries to return to their former homes on All Souls’ Night and partake of the food of the living. In Tyrol, cakes are left for them on the table and the room kept warm for their comfort. In Brittany, people flock to the cemeteries at nightfall to kneel, bareheaded, at the graves of their loved ones, and to anoint the hollow of the tombstone with holy water or to pour libations of milk on it. At bedtime, the supper is left on the table for the souls. In Bolivia, many people believe that the dead eat the food that is left out for them. Some claim that the food is gone or partially consumed in the morning.

The Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexico and other countries can be traced back to the indigenous peoples such as the Olmec, Zapotec, Mixtec, Mexican, Aztec, Maya, P’urhépecha, and Totonac. Rituals celebrating the deaths of ancestors have been observed by these civilizations perhaps for as long as 2500–3000 years. In the pre-Hispanic era, it was common to keep skulls as trophies and display them during the rituals to symbolize death and rebirth.

The festival that became the modern Day of the Dead fell in the ninth month of the Aztec calendar, about the beginning of August, and was celebrated for an entire month. The festivities were dedicated to the goddess Mictecacihuatl, known as the “Lady of the Dead,” corresponding to the modern Catrina.

In most regions of Mexico, November 1st honors deceased children and infants where as deceased adults are honored on November 2nd. This is indicated by generally referring to November 1st mainly as “Día de los Inocentes” (Day of the Innocents) but also as “Día de los Angelitos” (Day of the Little Angels) and November 2nd as “Día de los Muertos” or “Día de los Difuntos” (Day of the Dead).

Many people believe that during the Day of the Dead, it is easier for the souls of the departed to visit the living. People will go to cemeteries to communicate with the souls of the departed, and will build private altars, containing the favorite foods and beverages, and photos and memorabilia, of the departed. The intent is to encourage visits by the souls, so that the souls will hear the prayers and the comments of the living directed to them. Celebrations can take a humorous tone, as celebrants remember funny events and anecdotes about the departed.

Plans for the festival are made throughout the year, including gathering the goods to be offered to the dead. During the period of November 1 and November 2, families usually clean and decorate graves; most visit the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried and decorate their graves with ofrendas, or offerings, which often include orange marigolds called “cempasúchitl.” In modern Mexico this name is often replaced with the term “Flor de Muerto” (“Flower of the Dead”). These flowers are thought to attract souls of the dead to the offerings.

Toys are brought for dead children (los angelitos, or little angels), and bottles of tequila, mezcal, pulque or atole for adults. Families will also offer trinkets or the deceased’s favorite candies on the grave. Ofrendas are also put in homes, usually with foods such as candied pumpkin, pan de muerto (“bread of the dead”) or sugar skulls and beverages such as atole. The ofrendas are left out in the homes as a welcoming gesture for the deceased. Some people believe the spirits of the dead eat the “spiritual essence” of the ofrenda food, so even though the celebrators eat the food after the festivities, they believe it lacks nutritional value. Pillows and blankets are left out so that the deceased can rest after their long journey. In some parts of Mexico, such as the towns of Mixquic, Pátzcuaro and Janitzio, people spend all night beside the graves of their relatives.

Some families build altars or small shrines in their homes. These altars usually have the Christian cross, statues or pictures of the Blessed Virgin Mary, pictures of deceased relatives and other persons, and scores of candles. Traditionally, families spend some time around the altar praying and telling anecdotes about the deceased. In some locations, celebrants wear shells on their clothing so when they dance the dead will wake up because of the noise. Some will dress up as the deceased.

Public schools at all levels build altars with offerings, usually omitting the religious symbols. Government offices usually have at least a small altar, as this holiday is seen as important to the Mexican heritage.

Those with writing talent sometimes create short poems, called “calaveras” (“skulls”), mocking epitaphs of friends, sometimes describing interesting habits and attitudes or some funny anecdotes. This custom originated in the 18th-19th century, after a newspaper published a poem narrating a dream of a cemetery in the future, “and all of us were dead”, proceeding to “read” the tombstones. Newspapers dedicate calaveras to public figures, with cartoons of skeletons in the style of José Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican illustrator. Theatrical presentations of Don Juan Tenorio by José Zorrilla (1817–1893) are also traditional on this day.

Island Pacanda, Lake Patzcuaro Mexico – Dia de los MuertosA common symbol of the holiday is the skull (colloquially called calavera), which celebrants represent in masks, called calacas (colloquial term for “skeleton”), and foods such as sugar skulls, which are inscribed with the name of the recipient on the forehead. Sugar skulls are gifts that can be given to both the living and the dead. Other holiday foods include pan de muerto, a sweet egg bread made in various shapes, from plain rounds to skulls and rabbits often decorated with white frosting to look like twisted bones.

José Guadalupe Posada created a famous print of a figure that he called “La Calavera de la Catrina” (“calavera of the female dandy”), as a parody of a Mexican upper class female. Posada’s striking image of a costumed female with a skeleton face has become associated with the Day of the Dead, and Catrina figures often are a prominent part of modern Day of the Dead observances.

The traditions and activities that take place in celebration of the Day of the Dead are not universal and often vary from town to town. For example, in the town of Pátzcuaro on the Lago de Pátzcuaro in Michoacán the tradition is very different if the deceased is a child rather than an adult. On November 1 of the year after a child’s death, the godparents set a table in the parents’ home with sweets, fruits, pan de muerto, a cross, a Rosary (used to ask the Virgin Mary to pray for them) and candles. This is meant to celebrate the child’s life, in respect and appreciation for the parents. There is also dancing with colorful costumes, often with skull-shaped masks and devil masks in the plaza or garden of the town. At midnight on November 2, the people light candles and ride winged boats called mariposas (Spanish for “butterfly”) to Janitzio, an island in the middle of the lake where there is a cemetery, to honor and celebrate the lives of the dead there.

In contrast, the town of Ocotepec, north of Cuernavaca in the State of Morelos opens its doors to visitors in exchange for ‘veladoras‘ (small wax candles) to show respect for the recently dead. In return, the visitors receive tamales and ‘atole‘. This is only done by the owners of the house where somebody in the household has died in the previous year. Many people of the surrounding areas arrive early to eat for free and enjoy the elaborate altars set up to receive the visitors from ‘Mictlán‘.

In some parts of the country, children in costumes roam the streets, asking passersby for a calaverita, a small gift of money; they don’t knock on people’s doors.

Some people believe that possessing “dia de los muertos” items can bring good luck. Many people get tattoos or have dolls of the dead to carry with them. They also clean their houses and prepare the favorite dishes of their deceased loved ones to place upon an altar.

Collected from various sources.