Catholic

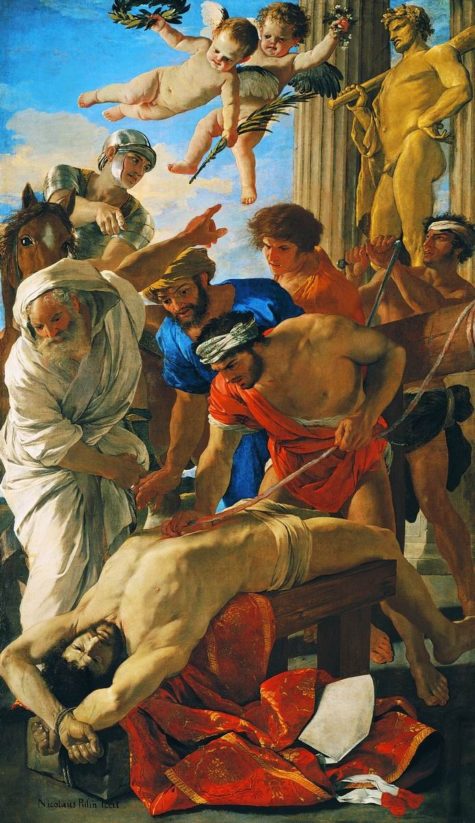

February 9th is the feast day of Saint Apollonia, patroness of dentistry and those suffering from toothache or other dental problems. It is believed that whoever says a prayer to Saint Apollonia should have no pain in his teeth on the day of the prayer.

Her story is as follows:

In a persecution of the Christians, stirred up by ” a certain poet of Alexandria,” she was seized, and all her teeth were beaten out, with threats that she should be cast into the fire ” if she did not utter certain impious words,” whereupon, of her own accord, she leaped into the flames.

This is the prayer:

” O Saint Apollonia, by thy passion, obtain for us the remission of all the sins, which, with teeth and mouth, we have committed through gluttony and speech; that we may be delivered from pain and gnashing of teeth here and hereafter; and loving cleanness of heart, by the grace of our lips we may have the king of angels our friend. Amen.”

— W. G. Willis Watsox.

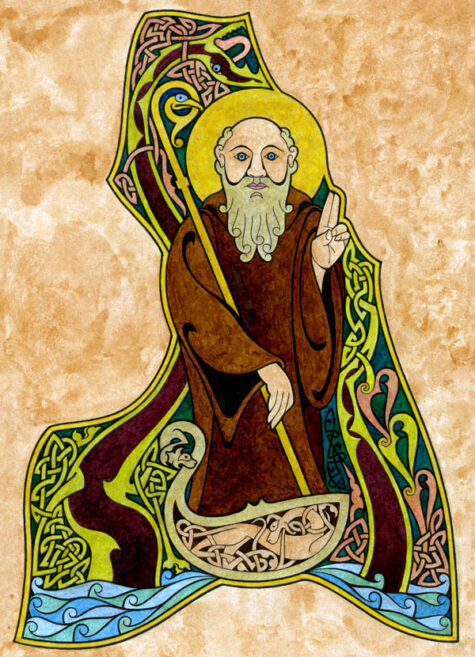

June 9 is St Columba’s day which is said to be the luckiest day of the year, so a good day to start any project you wish to flourish. St. Columba’s feast no longer appears on the General Roman Calendar, but is a Feast Day in Ireland’s National Calendar.

Saint Columba’s Feast Day has also been designated as International Celtic Art Day. The Book of Kells and the Book of Durrow, great medieval masterpieces of Celtic art, are associated with Columba.

St Columba is the patron saint of bookbinders and poets, and was said to have performed over a hundred miracles in his life – you don’t get saints like that any more! He did everything from expelling demons, calming storms and wild animals, and restoring a child to life, to more mundane miracles such as miraculously sending a staff to a colleague who had managed to leave it behind when he went on a voyage, and my favorite: exorcising a demon from a bucket and restoring the spilt milk to it.

There is even a story that has been interpreted as the first reference to the Loch Ness Monster. According to Adomnán, Columba came across a group of Picts burying a man who had been killed by the monster. Columba saves a swimmer from the monster with the sign of the Cross and the imprecation, “Thou shalt go no further, nor touch the man; go back with all speed.”

The beast flees, terrified, to the amazement of the assembled Picts who glorified Columba’s God. Whether or not this incident is true, Adomnán’s text specifically states that the monster was swimming in the River Ness – the river flowing from the loch – rather than in Loch Ness itself.

In another story, a poor farmer had only five cows; Columba blessed them, saying that the farmer would one day have 105 cows. Adomnán recorded that this came true, but didn’t say how long it took. He did say, though, that the man never had any more than 105 cattle: whenever the cattle reached that number, something would happen to the extra.

Columba would not, though, allow any cows on the island of Iona. He said that women always follow cows to tend them, and thus, cows bring trouble. One time, five men were fishing in the river Sale and caught only five fish. Columba said “God will provide a bigger fish for me; try your nets again,” and they caught the biggest salmon they had ever seen.

St. Columban, abbot, is the patron of shepherds, and one of the patron saints of Scotland. There is a tradition of rye or oat cakes baked in his memory.

A St Columba Day Story

There is a story which is told at this time of the year about the little children of northern Scotland, and our children of southern Ohio love to hear it. How easily we are united in brotherhood by common interest!

As June 8, the eve of St. Columba’s Day, arrives, our green hills are flicked with puffs of white wool. The older sheep have been sheared, but the fat little ones are as broad as they are long. The newborn ewe lambs have learned to skip and dance, while the young rams pretend to be very fierce as they bump their curly heads in play.

Just so the hills of the Hebrides must have looked when St. Columba and his twelve companions arrived in Scotland away back in the sixth century. The people were called Picts at that time and their lives depended upon sheep raising.

It was an easy step for them to understand the message of the Good Shepherd. St. Columba, in imitation of his Master, gathered Scotland’s souls to himself, gave them a sheepfold of faith in the island Monastery of Iona. As a “faithful and wise servant, whom his Lord setteth over his family, he gaveth them their measure of wheat in due season.”

It is true that he died at the foot of the altar while he was blessing “his sheep” in about the year 600, but some of his people remember him still.

Oak Cakes for St Columba Day

A rye or oat cake is baked in the Hebrides in honor of St. Columba. A small silver coin is placed in the dough, and the cake is toasted before a fire of rowan, yew or oak branches. The children of the house dance in impatience until the cake is finished because it is theirs and theirs alone.

Excitement rises to a fever pitch when the cake is divided, for the child who receives the silver coin has always gotten the crop of new lambs for the season. Families did know how to delegate authority before the days of 4-H groups. You see, young shepherds are trained on actual hills and on actual responsibility.

Here’s a recipe:

This oat flour cake is the perfect gluten and dairy-free treat. It is made with wholesome oats and sweetened with honey. It only requires one bowl so grab the ingredients and let’s start making this cake!

Oat flour is so easy to make, it is just ground oats! You can buy pre-made oat flour but it’s so much cheaper to make it yourself. Simply add quick cook or rolled oats to your blender or food processor; and blend until flour forms, approximately 30 seconds – 1 minute.

Measure your oat flour amount AFTER you have ground it into flour, this makes for a more accurate ratio in recipes. Also, make sure the oat flour is ground finely like traditional flour, otherwise, the cake will have a weird texture.

Use a metal or aluminum pan for this recipe, using a glass pan will result in uneven baking. The inside of the cake will be underdone and the outside will be very dark and possibly overcooked.

Ingredients

- 2 cups oat flour

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- ½ teaspoon baking soda

- ½ teaspoon cinnamon

- ½ teaspoon salt

- ¾ cup honey

- ¼ cup olive oil

- 1 teaspoon vanilla extract

- 2 eggs

Honey Coconut Frosting

- ½ cup coconut cream, from a can

- 2 tablespoons honey

Begin making the oat flour cake by preheating the oven to 350 degrees F. Grease an 8×8 inch aluminum baking dish with cooking spray or line with parchment paper.

Next, add all of the ingredients to a large bowl and mix until well combined and smooth.

Pour the batter into the baking dish. Bake for 25-30 minutes, or until a toothpick comes out clean.

While the cake bakes, make the frosting. Scoop cream off the top of the can of coconut cream and add to a small bowl with 2 tablespoons of honey. Mix with a whisk or hand mixer until smooth.

Remove the cake from the oven and allow it to cool on a wire rack for about 15 minutes. Then remove the cake from the pan, frost, if desired and cut into equal-sized pieces. Enjoy!

Sources:

4th of June is St Saturnina’s day, patron saint of farmers and wine merchants – and who is now believed to be ‘purely legendary’.

I’d suggest that here we have yet another hidden Pagan festival, this time dedicated to farmers and wine growers. Saturnina is the feminine form of Saturn, the Roman god of farmers and those who work with the earth. At this time of year, and especially looking at her patronages, it would be reasonable to have a festival to encourage a good harvest for farmers and wine growers.

The Legend of St Saturnina

Her legend states that she came from a noble German family (her father was a king, and that she took a vow of celibacy at the age of twelve. When her parents forced her into marriage when she turned twenty, she fled from Germany into France.

The man to whom she had been promised, a Saxon lord, pursued her into France after receiving approval to do so from Saturnina’s parents. He found her hiding with some shepherds at Arras; she had been working as a maidservant. He attempted to rape her, and when she resisted him, he decapitated her.

The lord miraculously drowned in a fountain, and Saturnina then carried her own head in her hands, and as witnessed by the townspeople, carried her head to the church of St. Remi, which was in the next village: Sains-Les-Marquion. She was then buried there.

Another tradition states that Saturnina placed her head on a stone at Sains-lès-Marquion, proclaiming herself to be the last human sacrifice the town would ever suffer.

Sources:

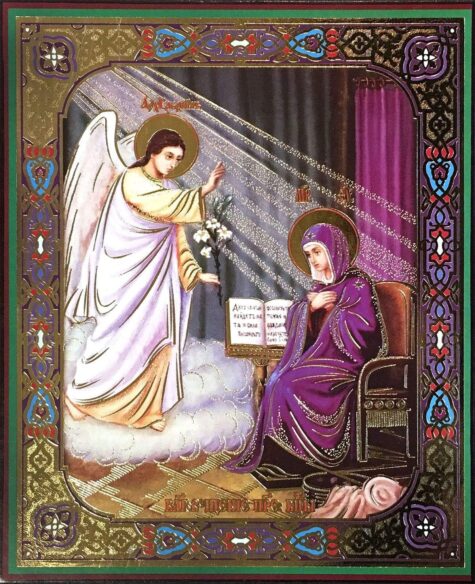

The precession of the equinoxes has moved the astronomical beginning of spring back four days to March 21, but its previous date of March 25 became identified with the Virgin Mary, who was told by the angel Gabriel on that day that she would become the mother of Christ.

Lady Day, as this day was commonly called, was one of the great quarterly dividing points of the year (the others being Midsummer Day, Michaelmas, and Christmas). It was traditionally the day for paying rents, signing or vacating leases, and hiring farm laborers for the year.

The flower cardamine, or lady’s-smock, with its milky white flowers, is dedicated to the Virgin Mary and appears about this time.

The Christian New Year’s Day

For centuries the Solemnity of the Annunciation on March 25, not Jan. 1, marked the first day of the New Year.

“Happy New Year!” is what we would have celebrated along with the Feast of the Annunciation on March 25 if we were living some centuries ago. Back then, the Annunciation also marked the start of the New Year.

The choice was well thought out and gives us lots to contemplate. Let’s begin at this point: when reforming the calendar in 45 B.C., Julius Caesar made Jan. 1 New Year’s Day. Celebrated with non-Christian festivities, of course.

Naturally, after Jesus life, death and resurrection, the Christians wanted to celebrate New Year’s Day in a spiritual way.

One early thought was to begin the year in springtime, a natural “new beginning.” And around the time of his Resurrection. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, what also came into play was the Jewish month of Nisan, which coincides with March and April on the Julian and Gregorian calendars and opens the sacred year.

But then arose the question, on which day should the New Year begin for Christians?

That answer really narrowed down when in the sixth century there came along the monk and abbot named Dionysius Exiguus, who lived in Rome. His name isn’t familiar today, but his work certainly is, especially in the use of B.C. and A.D. He established this way of dating from the birth of Jesus Christ — Before Christ and Anno Domini (the Year of Our Lord). Dionysius wanted to start the Christian era in order to reform the Roman calendar and way of calculating events. One of his great concerns was coming up with the date of Easter.

Naturally, the first day of the New Year had to fit somewhere in the new calendar. But where?

“Since March 25 was calculated as the date of the crucifixion of Jesus, there was a belief that one died on the same day that one was conceived,” writes Father John Fields, vice chancellor and director of communications for the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia. “If Jesus died on March 25 — the 14th of Nisan — then he was also conceived on the 14th of Nisan — March 25.” The date we celebrate the Annunciation. And the Incarnation.

But everyone didn’t adopt it immediately because the Julian calendar was still in widespread use. Besides, here and there in Europe, at times Dec. 25, the Nativity, was being celebrated as New Year’s.

Then along came the Council of Tours which in A.D. 567, put an end to Jan. 1 as New Year’s Day and adopted March 25 as the official first day of the New Year. Soon, yet slowly, countries in Europe were using that date to begin the official New Year. By the 8th century England had adopted this way of reckoning the year. The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that Charlemagne is believed to be the first Christian sovereign to use it.

Father Fields and other sources also point out that March 25 also had other implications. There was a general belief coming from early martyrologies and the early Church Fathers’ writings that March 25 was also the date on which Adam was created and which marked his fall, as well as other major events — the fall of Lucifer; Moses and the Israelites flight through the Red Sea; and Isaac offered in sacrifice by Abraham.

In 1582, along came Pope Gregory XIII who reformed the calendar. Doing so, for the calendar we now use, he placed New Year’s Day, the first day of the year, back to January 1. As he reformed the liturgical calendar also this became the Feast of the Circumcision.

But the Protestant countries weren’t so fast accepting the new Gregorian calendar. The British Empire continued to celebrate New Year’s Day on March 25 until finally adopting the Gregorian calendar on January 1, 1752.

“Until 1751, March 25 was also celebrated as New Year’s Day in the American colonies, since they were under British rule,” adds Father Fields.

Is March 25 still celebrated anywhere as New Year’s Day?

It sure is. In Tuscany in Italy. This year marks the 270th anniversary of the city of Pisa celebrating New Year’s Day on March 25. Florence does likewise (both celebrate the “other” New Year too). The event, begun in 1749, is quite colorful with concerts and festivals. Pisa has a procession to Pisa Cathedral which is dedicated to the Blessed Mother, while in Florence a local pilgrimage proceeds to the Basilica dell’Annunciazione.

So this March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation, remember that for centuries this feast day was the Christian New Year’s Day.

On March 25, instead of thinking of a weepy Auld Lang Syne sort of song, pray or recite with the greatest of joy the Magnificat. For through the Annunciation and Mary’s Fiat, Our Lord Jesus was incarnated and then crucified for our redemption. Now that’s something to really wish someone a Happy New Year about!

God Becomes A Man

The central focus of the Annunciation is Incarnation: God has become one of us. From all eternity God had decided that the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity should become human.

Now the decision is being realized. The God-Man embraces all humanity, indeed all creation, to bring it to God in one great act of love. Because human beings have rejected God, Jesus will accept a life of suffering and an agonizing death.

Mary has an important role to play in God’s plan. From all eternity, God destined her to be the mother of Jesus and closely related to him in the creation and redemption of the world. We could say that God’s decrees of creation and redemption are joined in the decree of Incarnation.

Because Mary is God’s instrument in the Incarnation, she has a role to play with Jesus in creation and redemption. It is a God-given role. It is God’s grace from beginning to end. Mary becomes the eminent figure she is only by God’s grace. She is the empty space where God could act. Everything she is she owes to the Trinity.

Together with Jesus, Mary is the link between heaven and earth. She is the human being who best, after Jesus, exemplifies the possibilities of human existence. She received into her lowliness the infinite love of God. She shows how an ordinary human being can reflect God in the ordinary circumstances of life. She exemplifies what the Church and every member of the Church is meant to become. She is the ultimate product of the creative and redemptive power of God. She manifests what the Incarnation is meant to accomplish for all of us.

Sometimes spiritual writers are accused of putting Mary on a pedestal and thereby, discouraging ordinary humans from imitating her. Perhaps such an observation is misguided. God did put Mary on a pedestal and has put all human beings on a pedestal. We have scarcely begun to realize the magnificence of divine grace, the wonder of God’s freely given love. The marvel of Mary—even in the midst of her very ordinary life—is God’s shout to us to wake up to the marvelous creatures that we all are by divine design.

Sources:

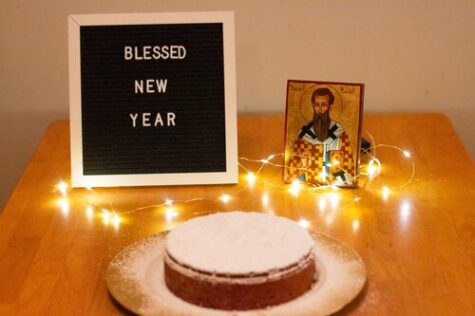

St. Basil’s Day, January 1st, commemorates the day in which (it’s believed) Basil of Caesarea died. The Festival of Saint Basil is the Greek New Year.

In Greek tradition, Basil brings gifts to children every January 1. Children leave their shoes by the fireplace in hopes that St. Basil will fill them with gifts. A large feast is prepared, the larger the luckier the year will be. Pork is usually the main dish. It is customary on his feast day to visit the homes of friends and relatives, to sing New Year’s carols, and to set an extra place at the table for Saint Basil.

Traditionally Vasilopita or Vaselopita, a special bread or cake, is baked on St. Basil’s Day Eve, and served at midnight. The cake is handed out in a particular order. The first piece is for the remembrance of St. Basil and the second is for the household. Those pieces are taken to the church to be blessed, then given to the poor. The rest of the slices are distributed from the eldest member of the household to the youngest.

A coin or trinket is hidden inside the cake, and the person who gets the piece with the hidden treasure will have luck in the coming year.

Vasilopita | St. Basil’s Bread

Make sure everyone knows a quarter is hidden in the cake so they search for it and do not choke on it.

- 1 cup butter, unsalted

- 2 cups granulated sugar

- 3 cups all-purpose flour

- 1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

- 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg

- 6 eggs

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 cup warm milk

- 1 tablespoon lemon juice

- zest of 1 orange

- zest of 1 lemon

- 1/4 cup blanched slivered almonds

- 2 tablespoons granulated sugar

- a clean quarter

Preheat oven to 350F. Generously grease a 10-inch round cake pan. Cream the butter and sugar together until light and fluffy. Stir in the flour, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Mix until mealy. Add the eggs one at a time, mixing well after each addition.

In a separate bowl, combine baking powder, baking soda, milk, lemon juice, and zests. Mix into the batter, then pour into prepared pan. Sprinkle with nuts and sugar. Bake 40-45 minutes. Gently push a quarter into the cake. Cool 10 minutes. Invert cake onto platter. Serve warm.

A Feast Day Prayer to Saint Basil

Saint Basil, O great follower of God, help all as well as me. Defender of orthodoxy, defend us too. Great follower of God, pray to him for all your people, as well as for unworthy me. Strong knight and leader of Ostrog, save us from the seen and unseen. Raised by Serbian soil to be the light in front of God, be our light and light up our road, and make the darkness disappear.

With prayer and tears you have warmed the cold cliffs of Ostrog, please warm our hearts with God’s spirit, so we can be saved. From all corners of the world to your grave come the weak and the ill, and you helped them, got rid of their demons as well as the devil, and healed their souls and bodies.

Please continue to help, the baptized and the nonbaptized, everybody and me as well. You brought peace to fighting brothers, please continue to bring peace, help the divided, make the sad happy, calm the stubborn, heal the sick. Saint Basil, O miracle worker, father of our spirit, listen and hear your children’s spirits in the name of Jesus Christ.

Amen.

About Saint Basil

Basil, being born into a wealthy family, gave away all his possessions to the poor, the underprivileged, those in need, and children. For Greeks and others in the Orthodox tradition, Basil is the saint associated with Santa Claus as opposed to the western tradition of St Nicholas

St. Basil, also called Saint Basil the Great, is one of the most distinguished Doctors of the Church and a forefather of the Greek Orthodox Church. St. Basil was born in the year 329 or 330 and died in the year 379. He is the Patron of Russia, Cappadocia, hospital administrators, reformers, monks, education, exorcism, and liturgists.

Basil’s life changed radically after he encountered Eustathius of Sebaste, a charismatic bishop and ascetic. Abandoning his legal and teaching career, Basil devoted his life to God. In a letter he described his spiritual awakening:

I had wasted much time on follies and spent nearly all of my youth in vain labors, and devotion to the teachings of a wisdom that God had made foolish. Suddenly, I awoke as out of a deep sleep. I beheld the wonderful light of the Gospel truth, and I recognized the nothingness of the wisdom of the princes of this world.

Hot-blooded and somewhat imperious, Basil was also generous and sympathetic. He personally organized a soup kitchen and distributed food to the poor during a famine following a drought. He gave away his personal family inheritance to benefit the poor of his diocese.

His letters show that he actively worked to reform thieves and prostitutes. They also show him encouraging his clergy not to be tempted by wealth or the comparatively easy life of a priest, and that he personally took care in selecting worthy candidates for holy orders. He also had the courage to criticize public officials who failed in their duty of administering justice. At the same time, he preached every morning and evening in his own church to large congregations.

In addition to all the above, he built a large complex just outside Caesarea, called the Basiliad, which included a poorhouse, hospice, and hospital, and was compared by Gregory of Nazianzus to the wonders of the world.

His three hundred letters reveal a rich and observant nature, which, despite the troubles of ill-health and ecclesiastical unrest, remained optimistic, tender and even playful. His principal efforts as a reformer were directed towards the improvement of the liturgy, and the reformation of the monastic institutions of the East.

There are numerous relics of Basil throughout the world. One of the most important is his head, which is preserved to this day at the monastery of the Great Lavra on Mount Athos in Greece. The mythical sword Durandal is said to contain some of Basil’s blood.

Some Great St Basil Quotes

I really love some of these quotes. They are surprisingly applicable to modern life. Enjoy!

Alternative St Basil Feast Days

According to some sources, Basil died on January 1, and the Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates his feast day together with that of the Feast of the Circumcision on that day. This was also the day on which the General Roman Calendar celebrated it at first; but in the 13th-century it was moved to June 14, a date believed to be that of his ordination as bishop, and it remained on that date until the 1969 revision of the calendar, which moved it to January 2 (rather than January 1) because the latter date is occupied by the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God.

On January 2 Saint Basil is celebrated together with Saint Gregory Nazianzen. Some traditionalist Catholics continue to observe pre-1970 calendars.

The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod commemorates Basil, along with Gregory of Nazianzus and Gregory of Nyssa on January 10.

The Church of England celebrates Saint Basil’s feast on January 2, but the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Church of Canada celebrate it on June 14.

In the Byzantine Rite, January 30 is the Synaxis of the Three Holy Hierarchs, in honor of Saint Basil, Saint Gregory the Theologian and Saint John Chrysostom.

The Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria celebrates the feast day of Saint Basil on the 6th of Tobi (6th of Terr on the Ethiopian calendar of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church). At present, this corresponds to January 14, January 15 during leap year.

Sources:

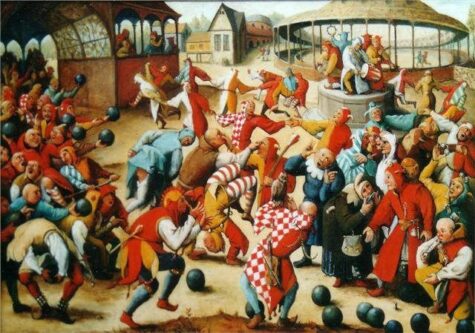

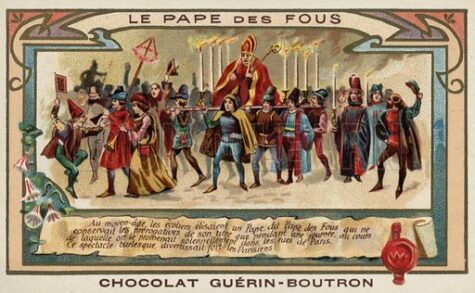

Feast of Fools was a celebration marked by wanton mischief and merrymaking. It took place in many parts of Europe, and particularly in France, every year during the later middle ages on or about the Feast of the Circumcision (1 Jan.). This feast day, as described by the French theologians who condemned it in 1445, sounds like a ton of fun.

This New Year’s Day celebration, they wrote, caught up high-ranking church officials in a bacchanal unworthy of their exalted positions.

“Priests and clerks may be seen wearing masks and monstrous visages at the hours of office,” the theologians recounted, presumably with a sniff of horror. “They dance in the choir dressed as women, panders or minstrels. They sing wanton songs. They eat black puddings… while the celebrant is saying mass. They play at dice… They run and leap through the church, without a blush at their own shame.”

The Feast of Fools was celebrated by the clergy in Europe during the Middle Ages, initially in Northern France, but later more widely. During the Feast, participants would elect either a false Bishop, false Archbishop or false Pope. Ecclesiastical ritual would also be parodied and higher and lower level clergy would change places.

It was known by many names:

- Festum

- Fatuorum

- Festum stultorum

- Festum hypodiaconorum

Officially banned in the 15th century, the Feast of Fools had its origins 300 years before, in the 1100s, and continued as a tradition well into the 16th century. It was memorialized in church documents condemning its excesses and in paintings depicting streets full of merry chaos. It appears in Victor Hugo’s famous 19th century novel, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, when Quasimodo is swept up in the festivities and crowned King of Fools.

This rowdy revelry may never has been quite as raucous as was rumored. It started out as a much tamer liturgical celebration, which accrued an outsized reputation for subversiveness. At its heart, though, the Feast of Fools always turned power on its head—a reversal that naturally made church leaders very nervous.

But outside the church doors, concurrent celebrations were much more irreverent. In these medieval centuries, Harris writes, it became popular for students to parade through the streets with their faces blackened with mud (or even animal dung) to conceal their identities while they parodied clergy, doctors, civil officials, and rulers. These parades certainly featured cross-dressing, drinking, singing, and all manner of other mischief and behavior that usually wouldn’t be tolerated.

Wintertime celebrations like these, where the less powerful parts of society had the chance to break loose for a day, trace their roots to Roman and other European pagan festivals of role-reversal. For a modern day take on this holiday, visit this Feast Of Fools post.

It is difficult to distinguish it from certain other similar celebrations, such as the Feast of Asses, and the Feast of the Boy Bishop. It seems to have grown out of a special “festival of the subdeacons”, which John Beleth, a liturgical writer of the twelfth century and an Englishman by birth, assigns to the day of the Circumcision.

He was among the earliest to draw attention to the fact that, as the deacons had a special celebration on St. Stephen’s day (26 Dec.), the priests on St. John the Evangelist’s day (27. Dec.), and again the choristers and mass-servers on that of Holy Innocents (28 Dec.), so the subdeacons were accustomed to hold their feast about the same time of year, but more particularly on the festival of the Circumcision.

This feast of the subdeacons afterwards developed into the feast of the lower clergy (esclaffardi), and was later taken up by certain brotherhoods or guilds of “fools” with a definite organization of their own. There can be little doubt — and medieval censors themselves freely recognized the fact — that the license and buffoonery which marked this occasion had their origin in pagan customs of very ancient date.

John Beleth, when he discusses these matters, entitles his chapter “De quadam libertate Decembrica“, and goes on to explain: “now the license which is then permitted is called Decembrian, because it was customary of old among the pagans that during this month slaves and serving-maids should have a sort of liberty given them, and should be put upon an equality with their masters, in celebrating a common festivity.” (P.L. CCII, 123).

The Feast of Fools and the almost blasphemous extravagances in some instances associated with it have constantly been made the occasion of a sweeping condemnation of the medieval Church.

There can be no question that ecclesiastical authority repeatedly condemned the license of the Feast of Fools in the strongest terms, no one being more determined in his efforts to suppress it than the great Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln. But these customs were so firmly rooted that centuries passed away before they were entirely eradicated.

In defense of the medieval Church one point must not be lost sight of. We possess hundreds, not to say thousands, of liturgical manuscripts of all countries and all descriptions. Amongst them the occurrence of anything which has to do with the Feast of Fools is extraordinarily rare. In missals and breviaries we may say that it never occurs.

In 1199, Bishop Eudes de Sully imposed regulations to check the abuses committed in the celebration of the Feast of Fools on New Year’s Day at Notre-Dame in Paris. The celebration was not entirely banned, but the part of the “Lord of Misrule” or “Precentor Stultorum” was restrained within decorous limits.

The central idea seems always to have been that of the old Saturnalia, i.e. a brief social revolution, in which power, dignity or impunity is conferred for a few hours upon those ordinarily in a subordinate position. Whether it took the form of the boy bishop or the subdeacon conducting the cathedral office, the parody must always have trembled on the brink of burlesque, if not of the profane.

We can trace the same idea at St. Gall in the tenth century, where a student, on the thirteenth of December each year, enacted the part of the abbot. It will be sufficient here to notice that the continuance of the celebration of the Feast of Fools was finally forbidden under the very severest penalties by the Council of Basle in 1435, and that this condemnation was supported by a strongly-worded document issued by the theological faculty of the University of Paris in 1444, as well as by numerous decrees of various provincial councils. In this way it seems that the abuse had practically disappeared before the time of the Council of Trent.

Sources:

Seven Sleepers’ Day (Siebenschläfertag) on June 27 is a feast day commemorating the legend of the Seven Sleepers as well as one of the best-known bits of traditional weather lore (expressed as a proverb) remaining in German-speaking Europe.

The atmospheric conditions on that day are supposed to determine or predict the average summer weather of the next seven weeks. and it is believed that whatever the weather is on this day, it will remain so for seven weeks.

Apparently this forecast is about as accurate as Groundhog Day forecasts in the U.S. The story of the Seven Sleepers has many versions and is widespread throughout the Christian and Muslim worlds. It has been told and retold repeatedly from ancient times to the present day.

The Story of the Seven Sleepers

The earliest Syriac version of the tale states that during the persecutions of the Roman emperor Decius, around 250, seven young men were accused of being Christians. They were given some time to recant their faith, but chose instead to give their worldly goods to the poor and retire to a mountain cave to pray, where they fell asleep.

The emperor, seeing that their attitude towards their faith had not changed, ordered the mouth of the cave to be sealed. Decius died in 251, and many years passed during which Christianity went from being persecuted to being the state religion of the Roman Empire. At some later time—usually given as during the reign of Theodosius II (408–450)—the landowner decided to open up the sealed mouth of the cave, thinking to use it as a cattle pen. He opened it and found the sleepers inside.

They awoke, imagining that they had slept for a single day, and sent one of their number to Ephesus to buy food, with instructions to be careful in case the Romans were to recognize him and seize him. Upon arriving in the city, this youth was astounded to find buildings with crosses attached. The townspeople for their part were amazed to find a man trying to spend old coins from the reign of Decius. The bishop was summoned to interview the sleepers; they told him their miracle story, and died praising God.

As the earliest versions of the legend spread from Ephesus, an early Christian catacomb came to be associated with it, attracting scores of pilgrims. On the slopes of Mount Pion near Ephesus, the cave of the Seven Sleepers with ruins of the church built over it was excavated in 1927–28. The excavation brought to light several hundred graves which were dated to the 5th and 6th centuries. Inscriptions dedicated to the Seven Sleepers were found on the walls of the church and in the graves. This cave is now a local tourist attraction.

The story of the Seven Sleepers is probably best known in the Muslim world. It is told in the Qur’an (Surah 18, verse 9-26). The Qur’anic rendering of this story doesn’t state exactly the number of sleepers; the exact number is believed to be known to God alone. It also gives the number of years that they slept as 300 solar years (equivalent to 309 lunar years).

Unlike the Christian story, the Islamic version includes mention of a dog who accompanied the youths into the cave, and was also asleep. But when people passed by the cave it looked as if the dog was just keeping watch at the entrance, making them afraid of seeing what is in the cave once they saw the dog. In Islam, these youths are referred to as “The People of the Cave.”

There are numerous retellings of the tale in early modern and modern literature. John Donne’s (1572-1631) poem “The good-morrow” contains the lines:

were we not wean’d till then?

But suck’d on country pleasures, childishly?

Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers’ den?”

A Recipe For Today

Given that the sleepers were hungry when they awoke and sent one of their number to buy food, I thought a local Turkish recipe found at roadside food stalls would be suitable for the day. Gözleme are flaky pastry packets stuffed with a mix of feta cheese and spinach plus herbs and spices. Variants can be found throughout Turkey and Greece. They can also be stuffed with ground lamb flavored with garlic, paprika, and cumin. Once in a while you will come across them with both fillings in one.

Ingredients:

Dough

- 2 cups (250 g) plain flour, unbleached

- 2 cups (250 g) wholemeal flour

- pinch of salt

- vegetable oil

Filling

- 2 cups (450 g) grated feta cheese or

- 2 cups (200 g) finely chopped spinach leaves

- ½ cup (50 g) chopped fresh mint leaves

- ½ cup (50 g)chopped flat leaf parsley

- ½ cup (80 g) chopped green onion

- ½ cup (80 g) diced white onion

- 1 tsp (5 g) white pepper

- 1 tsp (5 g) allspice

- 1 tsp (5 g) dried oregano

- 1 tsp (5 g) dried sage

Instructions:

Sift the flours and salt and mix with 1 ½ cups (210 ml) of water in an electric mixer with a dough hook or knead by hand for at least ten minutes.

Keep adding more water a little at a time until you get a very pliable, elastic dough that is easy to knead, but not so watery that it is too sticky to handle. Dust frequently with the extra flour.

Allow the dough to stand, covered, overnight (at least 10 hours). When ready to cook, divide the dough into six round portions. Dust with flour. Roll one of the rounds flat with a rolling pin on a flour-dusted surface, into a rectangle shape, as thinly as possible.

Brush on a little oil, then fold over into a square. Fold over twice more into a square. Repeat the dusting, rolling out to a large rectangle, folding, oiling, dusting process three more times. Repeat the entire process for each of the six rounds

Take one of the folded dough squares and roll it out very thinly for the final time, into a large square. Sprinkle on the filling sparingly – – as you would for a pizza topping but on half of the square only.

Start with a layer of cheese. Mix the spinach, mint, green onion and parsley together in a bowl, and add some of this as the next layer. Mix together the white onion, spices, and dried herbs, and add some as a final topping.

Fold over the uncovered half of the square to cover the filling. Press down lightly all over.

Cook on a pre-heated oiled heavy skillet (cast iron if possible). Make sure the skillet is not too hot. It takes about 10 minutes to cook everything through. Turn them often until the outside is golden and crisp. Cut into smaller squares and serve with lemon wedges. Yield 6.

Some Weather Science

The Seven Sleepers singularity is contested as quite inaccurate in practice. Objections have been raised that the weather lore associated with the day might have arisen before the 1582 Gregorian calendar reform, and as at this time the difference to the Julian calendar amounted to ten days, July 7 would be the actual Seven Sleepers Day. Based on this date the prediction has a slightly increased probability of about 55–70%, if confined to the southern parts of Germany, where the rule seems to have originated. In contrast, the weather lore is not applicable to Northern Germany and its rather oceanic climate.

Depending on the meandering flow of the polar jet stream in the Northern Hemisphere (Rossby waves) and the emergence of veering low-pressure and high-pressure (anticyclone) systems, the atmospheric conditions tend to stabilize in early July: either a high-pressure ridge takes hold over Scandinavia, which may coalesce with the subtropical Azores High to form a stable and warm macro weather situation; or a high North Atlantic oscillation between the Icelandic Low and the Azores High implies a long-standing influx of wet air masses into Central Europe.

Sources:

The 2nd of June is St Erasmus of Formia’s day – better known as St Elmo. He is said to have kept preaching during a thunderstorm and even when lightning struck near him. Sailors therefore look on the electrical discharges that hit masts or other protuberances as a sign that the saint is watching over them, and call this St Elmo’s Fire.

St. Elmo’s fire is a bright blue or violet glow, appearing like fire in some circumstances, from tall, sharply pointed structures such as lightning rods, masts, spires and chimneys, and on aircraft wings or nose cones. St. Elmo’s fire can also appear on leaves and grass, and even at the tips of cattle horns. Often accompanying the glow is a distinct hissing or buzzing sound. It is sometimes confused with ball lightning.

Invoking Saint Erasmus

In addition to being the patron saint of sailors, Saint Erasmus is also the patron saint of a host of other groups, including explosives workers, ordnance workers, and women in labor. He is also invoked against colic, birth pains, intestinal disorders, stomach diseases, and storms. He is one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, a group of saints regarded as special protectors against various illnesses.

Invocation of St. Erasmus

Holy martyr Erasmus, who didst willingly and bravely bear the trials and sufferings of life, and by thy charity didst console many fellow-sufferers; I implore thee to remember me in my needs and to intercede for me with God. Staunch confessor of the Faith, victorious vanquisher of all tortures, pray Jesus for me and ask Him to grant me the grace to live and die in the Faith through which thou didst obtain the crown of glory. Amen.

Account of His Life and Martyrdom

Erasmus was Bishop of Formia, Italy. During the persecution against Christians under the emperors Diocletian (284-305) and Maximian Hercules (284-305), he left his diocese and went to Mount Libanus, where he hid for seven years. However, an angel is said to have appeared to him, and counseled him to return to his city.

On the way, he encountered some soldiers who questioned him. Erasmus admitted that he was a Christian and they brought him to trial at Antioch before the emperor Diocletian. After suffering terrible tortures, he was bound with chains and thrown into prison, but an angel appeared and helped him escape.

He passed through Lycia, where he raised up the son of an illustrious citizen. This resulted in a number of baptisms, which drew the attention of the Western Roman Emperor Maximian who, according to Voragine, was “much worse than was Diocletian.” Maximian ordered his arrest and Erasmus continued to confess his faith. They forced him to go to a temple of the idol, but along the saint’s route all the idols fell and were destroyed, and from the temple there came fire which fell upon many of the pagans.

That made the emperor so angry he had Erasmus enclosed in a barrel full of protruding spikes, and the barrel was rolled down a hill. But an angel healed him. Further tortures ensued.

When he was recaptured, he was brought before the emperor and beaten and whipped, then coated with pitch and set alight (as Christians had been in Nero’s games), and still he survived. Thrown into prison with the intention of letting him die of starvation, St Erasmus managed to escape.

He was recaptured and tortured some more in the Roman province of Illyricum, after boldly preaching and converting numerous pagans to Christianity. Finally, according to this version of his death, his stomach was slit open and his intestines wound around a windlass. This version may have developed from interpreting an icon that showed him with a windlass, signifying his patronage of sailors.

Sources:

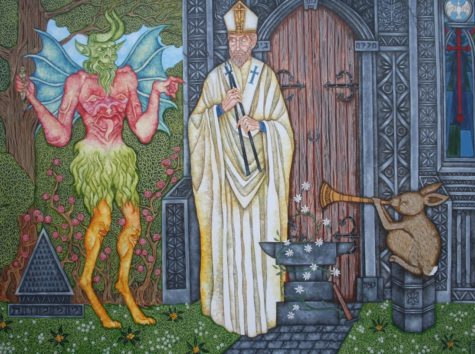

Traditional weather lore has it that St. Dunstan was a great brewer who sold himself to the devil on the condition that the devil would blight the apple trees to stop the production of cider, Dunstan’s rival drink. This is said to be the cause of the wintry blast that usually comes about this time. (May 19)

Foggier yet, and colder! Piercing, searching, biting cold. If the good Saint Dunstan had but nipped the Evil Spirit’s nose with a touch of such weather as that, instead of using his familiar weapons, then, indeed, he would have roared to lusty purpose.

~A Christmas Carol

This piece of folklore seeks to explain the late May frosts, known as ‘Franklin Days’ in the West Country, which often hit between 17-19 or 19-21 May. The tale was apparently particularly popular in Devon in the 19th and 20th centuries and goes thus:

Dunstan had bought some barley and made some beer, which he then hoped to sell for a good price. Seeing this the Devil appeared before him and offered to blight the local apple trees with frost (the tale is presumably set in Somerset, perhaps when Dunstan is Abbot of Glastonbury). This would ensure there was no cider and so drive demand for beer. Dunstan accepted the offer but stipulated that the frost should strike from the 17-19 May.

Stories About St. Dustan and the Devil:

According to legend, St. Dunstan had a number of encounters with the devil. The most famous story, which entered popular folklore, tells how he pulled the devil by the nose with his blacksmith’s tongs.

The story goes that while he was living as a hermit in a cell at Glastonbury, he occupied himself with various crafts, including metalwork. Against the old church of St Mary he built a small cell five feet long and two and a half feet deep. It was there that Dunstan studied, worked at his handicrafts, and played on his harp. It is at this time, according to a late 11th-century legend, that the Devil is said to have tempted Dunstan.

One day, as evening was coming on, an old man appeared at his window and asked him to make a chalice for him. Setting aside what he was working on, Dunstan agreed to the request and set to work. But as he was working his visitor began to change shape: one moment he was an old man, then a young boy, then a seductive woman.

Dunstan realized that his guest was the devil; but, pretending not to notice, he went on with his task. He took up the tongs from among his tools and laid them in the fire, waiting until they were red-hot. Then, pulling them out of the fire, he turned round and seized the devil by the nose with the tongs. The devil struggled and screamed, but Dunstan held on until at last he felt he had triumphed. Then he threw the devil out of his cell and it fled, running down the street and crying “Woe is me! What has that bald devil done to me? Look at me, a poor wretch, look how he has tortured me!”

St Dunstan stood in his ivied Tower,

Alembic, crucible, all were there;

When in came Nick to play him a trick,

In guise of a damsel passing fair.

Every one knows

How the story goes:

He took up the tongs and caught hold of his nose.

~Lay of St Dunstan, 1840

Many people heard and saw this, and the following day they came to Dunstan and asked him what had happened. He said to them, “These are the tricks of devils, who try to trap us with their snares whenever they can. But if we remain firm in the service of Christ, we can easily defeat them with his help, and they will flee from us in confusion.” And from that time he dwelt safely in his little cell.

The story was of course retold in other forms, as here in playful fashion in the South English Legendary:

þe deuel he hente bi þe nose & wel faste drou;

He twengde & ssok hure bi þe nose þat þe fur out blaste.

þe deuel wrickede here & þere & he huld euere faste,

He 3al & hupte & drou a3en & made grislich bere.

He nolde for al is bi3ete þat he hadde icome þere!

Wiþ is tonge he strok is nose & twengde him euere sore,

Forte it was wiþinne ni3te þat he ne mi3te iseo namore.

þe ssrewe was glad & bliþe inou þo he was out of is honde

And flei & gradde bi þe lift þat me hurde into al þe londe:

“Out, wat haþ þis calwe ido? wat haþ þis calwe ido?”

In þe contreie me hurde wide hou þe ssrewe gradde so.

As god þe ssrewe hadde ibeo habbe ysnut atom is nose,

He ne hi3ede namore þuderward to tilie him of þe pose.

He seized the devil by the nose and pulled very hard; he tweaked and shook him by the nose so that fire burst out. The devil wriggled here and there, and he still held fast. He yelled and hopped and pulled away and made a horrible commotion. He wished for all the world that he’d never come there! With his tongs Dunstan yanked at his nose and nipped him very sore, until night came on and he could no longer see. The villain was glad and happy indeed that he was out of his hands, and fled and cried out so it was heard all over the land: “Alas, what’s this bald one done? What’s this bald one done?” It was heard far around how the wicked one cried out. The villain had got such a good tweaking of his nose, he never hurried back there again to heal his cold!

On another occasion, when Dunstan was praying alone, the devil appeared to him in the likeness of a wolf with a gaping mouth, snarling and baring his teeth. Dunstan would not be distracted from concentration on his prayers, so the devil suddenly changed himself into a little fox, trying to get Dunstan’s attention by jumping about, contorting himself and trying to get Dunstan to laugh at him.

But, smiling a little, Dunstan only said, “You are revealing how you usually behave: by your tricks you flatter the unwary so that you can devour them. Now get out of here, wretch, since Christ, who crushed the lion and the dragon with his heel, will overcome you by his grace through me, whether you’re a wolf or a fox.”

Another legend regarding the Devil and St. Dunstan also occurred in Mayfield when the convent there had just been built. The Devil appeared to St. Dunstan and said that he was going to knock down all the houses in the village. St. Dunstan bargained with the Devil and got him to agree to leave standing any house with a horseshoe on the outside. At that time, the custom of nailing horseshoes to doors for luck wasn’t well known so the Devil agreed but St. Dunstan managed to nail a horseshoe to all the houses in the village before the Devil could get to them so the village was saved.

The Devil managed to get some measure of revenge against St. Dunstan by repeatedly setting Mayfield church, then built of wood, off its normal East-West axis, leaving St. Dunstan to repeatedly correct it. According to the lore, this was accoplished by pushing the church back into the proper east-west alignment with his shoulder!

Another church is involved with yet another St. Dunstan story. This time it is the steeple of the church in the village of Brookland, just over the border into Kent. The Devil took the steeple and was chased by St. Dunstan who caused the Devil to drop the steeple near Hastings by application of the tongs mentioned in the Mayfield story.

According to one version of the story, the injured devil flew off from Mayfield to cool his nose in the springs of Tunbridge Wells, and that’s how its famous waters got their reddish tint (don’t let anyone tell you it’s because of the iron in the water). Alternatively, he flew away with the tongs still attached to his nose, and they dropped off in the place near Brighton which is now called Tongdean (for, I hope, obvious reasons).

About Saint Dustan:

- Feastday: May 19

- Patron of armorers, goldsmiths, locksmiths, and jewelers

Born of a noble family at Baltonsborough, near Glastonbury, England, Dunstan was educated there by Irish monks and while still a youth, was sent to the court of King Athelstan. He became a Benedictine monk about 934 and was ordained by his uncle, St. Alphege, Bishop of Winchester, about 939.

After a time as a hermit at Glastonbury, Dunstan was recalled to the royal court by King Edmund, who appointed him abbot of Glastonbury Abbey in 943. He developed the Abbey into a great center of learning while revitalizing other monasteries in the area. He became advisor to King Edred on his accession to the throne when Edmund was murdered, and began a far-reaching reform of all the monasteries in Edred’s realm.

Dunstan also became deeply involved in secular politics and incurred the enmity of the West Saxon nobles for denouncing their immorality and for urging peace with the Danes. When Edwy succeeded his uncle Edred as king in 955, he became Dunstan’s bitter enemy for the Abbot’s strong censure of his scandalous lifestyle. Edwy confiscated his property and banished him from his kingdom.

Dunstan went to Ghent in Flanders but soon returned when a rebellion replaced Edwy with his brother Edgar, who appointed Dunstan Bishop of Worcester and London in 957. When Edwy died in 959, the civil strife ended and the country was reunited under Edgar, who appointed Dunstan Archbishop of Canterbury. The king and archbishop then planned a thorough reform of Church and state.

Dunstan was appointed legate by Pope John XII, and with St. Ethelwold and St. Oswald, restored ecclesiastical discipline, rebuilt many of the monasteries destroyed by the Danish invaders, replaced inept secular priests with monks, and enforced the widespread reforms they put into effect. Dunstan served as Edgar’s chief advisor for sixteen years and did not hesitate to reprimand him when he thought it deserved.

When Edgar died, Dunstan helped elect Edward the martyr king and then his half brother Ethelred, when Edward died soon after his election. Under Ethelred, Dunstan’s influence began to wane and he retired from politics to Canterbury to teach at the Cathedral school and died there. Dunstan has been called the reviver of monasticism in England. He was a noted musician, played the harp, composed several hymns, notably Kyrie Rex splendens, was a skilled metal worker, and illuminated manuscripts.

Sources:

The feast day of St Agathius is May the 7th, (formerly May 8th). It is unclear why the date was changed, and some information online still has it listed as May the 8th. He is a patron saint of soldiers, and most often invoked against headaches.

- About him:

Saint Agathius (Greek: Ακακιος; died 303), also known as Achatius or Agathonas or Acacius of Byzantium, according to Christian tradition, was a Cappadocian Greek centurion of the imperial army, martyred around 304.

Agathius was arrested on charges for being a Christian by Tribune Firmus in Perinthus, Thrace, tortured and then brought to Byzantium where he was scourged and beheaded, being made a martyr because he would not renounce his Christian faith. The date of his martyrdom is traditionally May 8, when his feast is observed.

- Note:

St. Acacius the Centurion is not to be confused with the St. Acacius who was crucified in the second century along with 10,000 (!) companions. Neither of these martyrs is the St. Achatius numbered among the “14 Holy Helpers.”

- For Headaches:

I’ve found that amethyst is one of the best gemstones to help relieve headaches and reduce stress and tension. You can simply sit quietly and hold a piece of amethyst against your forehead, or you could make a gem elixir so that you can take a drop or two of the liquid when necessary.

Another traditional spell is to find a pebble and hold it against your head and say: ‘Pain from my head go into this stone, go into this stone, go into this stone. Pain from my head go into this stone, go into this stone and stay there.’ Then take the stone outside and hurl it away from you with as much force as you can manage.

Sources: