Catholic

St. Agatha was tortured and martyred in 251 A.D. In addition to many other tortures, her were breasts cut off. In Catania, Sicily, and other places around the world, her feast day is celebrated with masses in her honor, large processions and symbolic foods, such as le minni di Sant’Agata (breasts of St. Agatha) or le minni di virgini (breasts of the virgin).

According to the story, not only did 15-year-old Saint Agatha of Sicily refuse to abandon her faith, she also rejected a Roman governor’s advances. As such, she was punished with torture and by having her breasts amputated, then died of her wounds in prison on February 5, 251 A.D. Frescoes of the mutilated martyr are easily recognizable. She’s often depicted holding her breasts on a platter.

Each February, hundreds of thousands of people flock to Catania to honor Saint Agatha in a three-day celebration. The centuries-old festival features an all-night procession and delicious replicas of saintly, amputated breasts at every pastry shop.

Known as minne di Sant’ Agata in Italian, these sweet cheese and marzipan desserts are an edible reminder of Saint Agatha’s suffering. Bakers craft the perfectly round confections using a base of shortcrust pastry topped with ricotta. After adding in chocolate or a piece of boozy spongecake to accompany the filling, they blanket everything in pistachio marzipan and a thick, creamy glaze. A candied cherry on top completes the anatomically-correct aesthetic.

Traditionally, the breasts of Saint Agatha pastries consist of a delicate outer layer of pasta frolla (shortbread dough) in the shape of a breast, stuffed with custard, zuccata, chopped almond or pistachio, covered with pink icing and topped with a half candied cherry; another version is filled with ricotta and covered with white icing and topped with a chocolate chip. For a great recipe visit this post, The Breasts Of Saint Agatha

St Agatha’s Party

Every year Catania, on the 3rd, 4th and 5th of February, offers to the Patron Saint such an extraordinary festival that can be compared only the holy week of or Seville or the Corpus Domini of Cuzco, in Perù. In those three days everybody and everything is concentrated on this fest, a mixture of devotion and folklore that attracts millions of people, either devoted or tourist.

The first day is dedicated to the candles offer. The traditions suggests that candle has to be as tall or heavy as the person that is demanding protection. Two carriages of eighteenth century, property once of the old city government, and eleven “candelore“, big candles, in representation of each corporation, are walked in procession.

February 4th it is the most exciting day, in fact it is the first day when the town “meets” the Patron Saint. Already at dawn time, the town is full of people. The devotees are wearing the traditional “sacco”, a votive dress of white cloth, very long and tight up with a string.

The “giro“, the procession on this day lasts all day long. The statue is walked in procession through the places of the martyrdom and in this way the story of the “Santuzza” is interlaced with the town story. On the statue, red gillyflowers (martyrdom symbol) are replaced with white gillyflowers (purity symbol).

On February 5th, during the day in the cathedral the pontifical mass is celebrated. At sun set time, the statue is walked in procession again, going through the centre of Catania. The most beautiful moment is when the statues goes to through “via San Giuliano” that because of its slope is very dangerous.

A Prayer To Saint Agatha

St. Agatha is the patron saint of Sicily, bellfounders, breast cancer patients, Palermo, rape victims, and wet nurses. She is also considered to be a powerful intercessor when people suffer from fires. Her feast day is celebrated on February 5.

- Prayer for healing:

Saint Agatha, you suffered sexual assault and indignity because of your faith and purity. Help heal all those who are survivors of sexual assault and protect those women who are in danger. Amen

- Prayers for persons suffering from breast cancer.

Pause for a moment to pray for all those suffering from breast cancer. Below is a traditional prayer to St. Agatha that may be used for this intention.

St. Agatha, woman of valor, from your own suffering we have been moved to ask your prayers for those of us who suffer from breast cancer. We place the NAME(S) before you, and ask you to intercede on their behalf. From where you stand in the health of life eternal — all wounds healed, and all tears wiped away — pray for [MENTION YOUR REQUEST], and all of us. Pray God will give us His holy benediction of health and healing. And, we remember you were a victim of torture and that you learned, first hand, of human cruelty and inhumanity.

We ask you to pray for our entire world. Ask God to enlighten us with a “genius for peace and understanding.” Ask Him to send us His Spirit of Serenity, and ask Him to help us share that peace with all we meet. From what you learned from your own path of pain, ask God to give us the Grace we need to remain holy in difficulties, not allowing our anger or our bitterness to overtake us.

Pray that we will be more peaceful and more charitable. And from your holy pace in our mystical body, the Church, pray that we, in our place and time will, together, create a world of justice and peace.

From 365 Goddess:

- Themes: Health; Well-Being; Protection

- Symbols: Any Health-related Items

- Presiding Goddess: Saint Agatha

About Agatha:

Saint Agatha was a third century Italian martyr who now presides over matters of health and protects homes from fire damage. Many nurses and healers turn to her for assistance in their work. While this saint was a historical persona (not simply a rewritten goddess figure), she certainly embodies the healthy guardian energies of the goddess.

To Do Today:

Traditionally, candles are taken from a central location to people’s homes to bring Agatha’s blessings. So, get yourself a special Agatha candle, of any color, and light it in a safe place whenever you feel under the weather.

Take out your first aid kit, over the counter medications, prescription medications, band aids and bandages and bless them today, saying:

Restore vitality, well-being impart,

Saint Agatha, hear the cry of my heart.

On these tools of healing your blessing give,

That I may stay healthy as long as I live.

When you use any item in the first-aid kit, you can activate the restorative magic by repeating the incantation.

To protect your home from fire, take a sprig of mistletoe left over from the holiday season and put it near your hearth. Invoke Saint Agatha’s protection by saying:

Saint Agatha, let my home be protected,

Let these fires ne’er be neglected.

If you don’t have mistletoe, substitute any red colored stone.

Sources:

These baked “breasts” are one of many different versions of pastries made in honor of St. Agatha, the patron saint for breast cancer. St. Agatha was tortured and martyred in 251 A.D. In addition to many other tortures, her breasts were cut off. In Catania, Sicily, and other places around the world, her feast day (Saint Agatha’s Day) is celebrated with masses in her honor, large processions and symbolic foods, such as le minni di Sant’Agata (breasts of St. Agatha) or le minni di virgini (breasts of the virgin).

Traditionally, the breasts of Saint Agatha pastries consist of a delicate outer layer of pasta frolla (shortbread dough) in the shape of a breast, stuffed with custard, zuccata, chopped almond or pistachio, covered with pink icing and topped with a half candied cherry; another version is filled with ricotta and covered with white icing and topped with a chocolate chip.

Personally, I prefer an unfrosted version (shown above) as it looks more realistic. My daughter and I actually made these, and they were delicious! We couldn’t decide which filling was better, so I’ve included both recipes. One is for a yummy orange flavored ricotta cream filling that stood up quite well to the molding process. The other is for a pastry cream that was also really yummy, but a little more difficult to work with when molding the breasts because it was so soft.

Ricotta Cream Filling – Make in advance and chill.

- 1 lb Ricotta (drained overnight)

- 2 tbsp Mascarpone

- 1/2 cup sugar

- zest of 1 orange

- 1 tbsp Grand Marnier

Cream together the ricotta, mascarpone and suger. When it is smooth and fluffy add in the orange zest and Grand Marnier. Mix well and chill until ready to use.

Pastry Cream Filling – Make in advance and chill

- 1 1/4 cups milk (whole or 2%)

- 1/2 vanilla bean, split lengthwise or 1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract or vanilla bean paste

- 3 large egg yolks

- 1/4 cup granulated white sugar

- 2 tablespoons all-purpose flour

- 2 tablespoons cornstarch

- 1/2 tablespoon liqueur (Grand Marnier, Brandy, Kirsch)

Dried Cherry, dried apricots, chocolate chips, or almonds (your choice) are used for the “nipple” of the breast shaped pastry.

In a medium-sized heatproof bowl, mix the sugar and egg yolks together. (Do let the mixture sit too long or you will get pieces of egg forming.) Sift the flour and cornstarch (corn flour) together and then add to the egg mixture, mixing until you get a smooth paste.

Meanwhile, in a saucepan bring the milk and vanilla bean just to boiling (just until milk starts to foam up.) Remove from heat and add slowly to egg mixture, whisking constantly to prevent curdling. (If you get a few pieces of egg (curdling) in the mixture, pour through a strainer.) Remove vanilla bean, scrape out seeds, and add the seeds to the egg mixture. (The vanilla bean can be washed and dried and placed in your sugar bowl to give the sugar a vanilla flavor.) Then pour the egg mixture into a medium saucepan and cook over medium heat until boiling, whisking constantly.

When it boils, whisk mixture constantly for another 30 – 60 seconds until it becomes thick. Remove from heat and immediately whisk in the liqueur (if using). (Stir in vanilla extract if using instead of a vanilla bean.) Pour into a clean bowl and immediately cover the surface with plastic wrap to prevent a crust from forming. Cool to room temperature. If not using right away refrigerate until needed, up to 3 days. Whisk or stir before using to get rid of any lumps that may have formed.

- You will also need:

Egg wash – We beat up an egg and added a small amount of water to it. You could also use the egg whites left over from the pasta frolla.

And to decide what you want to use for the “nipple” of these breast shaped pastries. We used semisweet chocolate pieces in some and raisins in others, but dried cherries, dried apricots, or almonds would work equally well.

Pasta Frolla for the Shells

- 4 cups sifted all purpose flour

- 1 cup granulated sugar

- 1/2 lb (2 sticks) salted butter

- 1 tbsp Agave Nectar

- 5 medium egg yolks, lightly beaten

- zest from 1 lemon

- 1/2 teaspoon baking powder

- 1 tablespoon Cognac

Mound flour on a flat surface and form a well or place into a bowl. Add the rest of the ingredients. Use your hands and mix it until it will shape into coarse crumbs of diverse sizes. Knead and bring the mixture together to form a ball. Fold and press with the palm of your hands; if dough is sticky, add some more flour, if it is too dry add a few tablespoons of water, to moisten it.

Do not over mix. Do not handle dough more than necessary. Form dough into a single mass and cover with a clean kitchen rag or with plastic wrap. Refrigerate dough from 30 minutes to 1 hour.

Preheat oven to 375 degrees and grease a baking sheet or line it with parchment paper.

Divide dough into 2 pieces and knead each piece briefly to compact; on a floured working surface, roll out one piece to 3/8 of an inch thick. Using a round cutter (or the rim of a glass) 3 inches across, cut 10 to 12 circles and place them 1 to 2 inches apart.on your greased baking sheet.

Knead the other piece of dough, adding in the scraps from the first. Compact it and roll it out 3/8 of an inch thick. Using a round cutter cut 10 to 12 circles slightly larger than the first set, and set aside.

Brush the first set of disks with the egg wash; place approximately 2 tablespoons of filling in the center of each one. Mound it up, but leave room around the edges. Put a chocolate chip or whatever you’ve decided to use for the “nipple” in the center on the top of the mound of filling.

Gently cover each with your second pastry circle. Carefully press it around the edges to seal it, as you do this, try to create a ‘breast-like: shape, pinching up on the pastry in the center to form a “nipple.” When it is pressed and sealed, use your round cutter to re-cut the edges. This will give your breast a nice round shape and help seal the edges even more. Remove the excess pastry dough.

Brush the formed pastries with egg wash. Bake the pastries for 15 or 20 minutes, or until they are a golden color. Place the pastries on a rack and allow them to cool before eating.

Credits:

Recipes for the Ricotta filling and the Pasta Frolla are by Sky Buletti. The pastry cream recipe was adapted from the Joy of Baking. Other fillings can be found at Sicilian Cooking Plus, and a nice tutorial on shaping the breasts can be found at Hi Cookery.

January 21 is the Eve of St Agnes. There are many traditions associated with both this night and tomorrow night, all intended to bring dreams of the future husband. Here are some of them.

- Walking thrice backwards around a churchyard in silence at midnight, scattering hemp seed over the left shoulder.

- Boiling an egg, removing the yolk and filling the center with salt and then eating the whole, shell included!

- Sticking 9 pins into a red onion, taking it backwards to the bedroom and sleeping with it under the pillow.

But the most often repeated one is that of making a Dumb Cake. Here are the instructions:

Three, five or seven maidens should gather together on St Agnes Eve and make a cake from flour, salt, eggs and water. While they are mixing and baking the cake all the girls should stand on something different and which they have never stood on before. Each girl should take a hand in adding each of the ingredients and each girl should turn the cake once. When the cake is baked they should eat it all between them. Then, walking backwards, they should all retire to bed where they will dream of their future husbands. The whole process from start to finish should take place in complete silence and should be completed just before midnight.

It is interesting that all these methods include the elements of silence, walking backward, and retiring to bed at midnight.

Here are some more old old spells for St Agnes night:

On Saint Agnes’ night, take a row of pins and pull out every one, one after another, saying a Pater Noster, sticking a pin in your sleeve, and you will dream of him or her you will marry. “Knit tne left garter about the right-legg’d stocking” (let the other garter and stocking alone), and as you rehearse these following verses, at every comma knit a knot:

“This knot I knit,

To know the thing I know not yet,

That I may see

The man that shall my husband be,

How he goes and what he wears.

And what he does all the days.”

Accordingly in your dream you will see him, if a musician, with a lute or other instrument; if a scholar, with a book,” and so on.

Another dream-charm for St . Agnes’ Eve was to take a sprig of rosemary and another of thyme and sprinkle them thrice with water, then place one in each shoe, and stand shoe and sprig on either side of the bed, repeating:

“St Agnes, that’s to lovers kind.

Come ease the trouble of my mind.”

In many places the notion prevailed that to insure the perfection of these charms the day must be spent in fasting. It was called “St . Agnes’ fast.”

Keat’s beautiful lines commemorative of the day seem doubly exquisite when read after conning the clumsy folk-rhymes:

They told me how upon St. Agnes’ Eve

Young virgins might have visions of delight,

And soft adorings from their loves receive

Upon the hony’d middle of the night.

IF ceremonies due they did aright;

As supperless to bed they must retire

And couch supine their beauties lily white;

Nor look behind, nor sideways, but require

Of heaven with upward eyes for all that they desire.

In Scotland the lasses sow grain at midnight on St . Agnes Eve, singing,—

“Agnes sweet and Agnes fair

Hither, hither now repair.

Bonny Agnes, let me see

The lad who is to marry me.”

And the figure of the future sweetheart appears as if reaping the grain.

Here is yet another one:

A key is placed in the Bible at the second chapter of Solomon’s Song, verses 1, 5 and 17, and the book tied firmly together, with the handle of the key left beyond the edges of the leaves. The tips of the little finger of the charm-tester and of a friend are placed under the side of the key, and then they “tried the alphabet” with the verses above named; that is, they began thus:

“A. My beloved is mine, and I am his. He feedeth among the lilies. Until the day break and the shadows fall away, turn, my beloved,” etc.

At the word “turn” the Bible was supposed to turn around if A were the first letter of the lover’s name. Thus could the entire name be spellled out.

Found in

Ethiopia follows the Ethiopian calendar, consequently Christmas falls on January 7th and Epiphany on January 19th. Timkat, Ethiopia’s Epiphany celebration, is a celebration of the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River. The festival lasts for three days and is at its most colorful in the capital, Addis Ababa, where everyone gets involved in the celebrations.

As part of the celebration, a ritual baptism is done. A stream or pool is blessed before dawn. The water is sprinkled on some participants, while other immerse themselves in the water to symbolically renew their baptismal vows.

Pilgrims come from far and wide to take part in the festival and witness the re-enactment of the baptism. All over the country large crowds assemble as the religious festivities commence, with spectacular processions, song, dance and prayer.

In Addis Ababa, the festival is particularly spectacular. The streets are adorned with green, red and yellow to represent the Ethiopian flag and priests walk through the streets holding colorful and richly decorated umbrellas.

The religious ceremony commences on the first day when the Tabot, a model of the Ark of the Covenant, which is present on every Ethiopian altar (somewhat like the Western altar stone), is reverently wrapped in rich cloth and borne in procession on the head of the priest.

The Tabots are then carried to the river in a procession led by the most senior priest of each church, who carry the arks on top of their heads. The Divine Liturgy is celebrated near a stream or pool early in the morning (around 2 a.m.). Then the nearby body of water is blessed towards dawn and sprinkled on the participants, some of whom jump in the water to renew their baptismal vows.

The second day of Timkat marks the main celebrations, with Orthodox Ethiopians from every segment of society merrily march through the streets in a riot of color, singing, dancing and feasting. All but one of the Tabots are returned to their respective churches.

On the third day of Timkat, known as the feast of St. Michael the Archangel, the Tabot of St. Michael’s Church is escorted back to its church in colorful procession and festivities.

About the Tabot

The Tabot symbolizes the Ark of the Covenant and the tablets describing the Ten Commandments, which God gave to Moses on Mount Sinai to serve as the core principles of the moral behavior for humanity. The Tabot, which is otherwise rarely seen by the laity, represents the manifestation of Jesus as the Messiah when he came to the Jordan for baptism.

The original Ark of the Covenant is said to be under permanent guard in Northern Ethiopia, protected by priests who have sworn never to leave the sacred grounds.

Sources:

Dwynwen was Wales’ patron saint of lovers, and January 25th is the Welsh equivalent to St Valentine’s Day. However, it is a romantic country, and they also celebrate St Valentine’s day on 14 February!

She is also known as:

- Dwyn

- Donwen

- Donwenna

- Dunwen

Her most well known saying is “Nothing wins hearts like cheerfulness”

The story of Dwynwen dates back to the 5th century. She was a beautiful Celtic princess, the prettiest of all the King of Wales’s 24 daughters (Brychan Brycheiniog of Brechon also had 11 sons!).

Dwynwen was in deeply in love with the handsome Maelon Dafodrill, but her father had already betrothed her to another, so he refused to give them his consent. On finding out, Maelon cruelly forced himself upon her and fled. With a broken heart, and grieved to have upset her father, Dwynwen ran to the woods and begged God to make her forget her love for Maelon.

Exhausted and aungished, Dwynwen eventually fell asleep. Whilst dreaming, an angel visited her and left a sweet smelling potion. This would erase all memories of Maelon, and his callous heart would also be cooled, but so much so that he turned to ice. Dwynwen was horrified to find her love frozen solid. She prayed again to God, who answered her prayers by granting her three wishes.

Her first wish was to have Maelon thawed and for him to forget her; her second, to have God look kindly on the hopes and dreams of true lovers whilst mending the broken hearts of the spurned; and her third was for her to never marry, but to devote the remainder of her life to God, as thanks for saving Maelon.

Dwynwen devoted the rest of life to God’s service. She became a nun and lived on Llanddwyn Island on the western coast of Ynys Mon (Anglesey), an area accessible only at low tide. She founded a church there, remains of which can still be seen today. After her death she was declared the Welsh Patron Saint of Lovers and ever since, Welsh lovers have looked to St Dwynwen for her help in courting their true love, or for forgetting a false one.

On the island there is a well where, according to legend, a sacred fish (an eel) swims. It is said that the eel can predict the happiness of relationships.

Her well, a fresh-water spring called Ffynnon Dwynwen, became a wishing well and place of pilgrimage, particularly for lovers because of the story above. The tradition grew that the eel in the well could foretell the future for lovers – ask questions and watch which way they turn. Women would scatter breadcrumbs on the surface, then lay her handkerchief on water’s surface; if the eel disturbed it, her lover would be faithful.

Visitors still go to the well today, hoping that the water will boil, meaning that love and good luck will follow them. Her well continues to be a place of pilgrimage; there’s a tradition that if the fish in the well are active when a couple visits, it’s the sign of a faithful husband.

Visitors would leave offerings at her shrine, and so popular was this place of pilgrimage that it became the richest in the area during Tudor times. This funded a substantial chapel that was built in the 16th century on the site of Dwynwen’s original chapel.

Prayer To St Dwynwen

Oh Blessed St. Dwynwen, you who knew pain and peace, division and reconciliation. You have promised to aid lovers and you watch over those whose hearts have been broken. As you received three boons from an Angel, intercede for me to receive 3 blessings to obtain my heart’s desire (state request) and if that is not God’s will, a speedy healing from my pain; your guidance and assistance that I may find love with the right person, at the right time, and in a right way; and an unshakeable faith in the boundless kindness and wisdom of God and this I ask in the name of Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

St. Dwynwen, we beseech thee, comfort lovers whose vision is unclear. Send mending to those with love lost. Protect companions. In your name we seek to do the same. In your name we choose love first. With the love of you, Mary and of Jesus Christ. Amen.

Sources:

Ethiopia follows the Ethiopian calendar, consequently Christmas or Genna ((also known as Lidet, or “birthday”) falls on January 7th,

Like most other Christian holidays, Christmas in Ethiopia, is celebrated in its own unique way. The main ceremonial activities of the holiday center around local Ethiopian Orthodox churches (though Protestants and Catholics also celebrate), which hold late-night services on Christmas Eve lasting well past midnight.

People dress in white and attend church. Everyone receives a candle as they enter the church. The candles are lit, and everyone walks around the church three times. People stand during mass. Males and females are separated.

Traditional liturgical singing marks these services, as does chanting performed by priests and deacons wearing colorful robes with gold and silver accents. Many people travel by foot from church to church, taking in various services until the light of dawn announces the arrival of Christmas morning.

The first Christmas meal is often an early breakfast, eaten by bleary-eyed congregants after returning home. The light meal likely starts with juice made from flaxseed (to oil up the intestines after 40 days of fasting) before moving on to the famously spicy chicken stew doro wot, and it most certainly includes appropriately strong Ethiopian coffee to help welcome the new day.

Later on, friends and relatives gather to enjoy a full Genna feast, usually involving a freshly killed lamb for mutton tibs and traditional beverages such as tej (honey wine). And though gift-giving does not figure very prominently in the Ethiopian Christmas tradition, the purchase of new clothing for the occasion — particularly for children — is seen as an important part of the festivities.

Several hundred families walking toward churches dressed as a sea of brilliant white cotton is a common sight throughout the country.

Perhaps the most unique aspect of the Ethiopian Christmas tradition is that it is associated with a sport, also called Genna, that is most widely played during the holiday season. According to Ethiopian legend, when the shepherds of the biblical Christmas story were informed of the birth of the Messiah, they expressed their overwhelming joy by using their staffs to break into a spontaneous game that resembles field hockey. The afternoon of Genna is filled with matches of the game, played mainly by young men, and potentially other sporting activities such as horse racing.

Although Genna is observed by Christians across Ethiopia, the most famous Christmas celebrations arguably occur in the historic city of Lalibela. There, crowds of up to 100,000 pilgrims flock to watch immaculately dressed Orthodox clergy perform the woreb lining the steep ledges surrounding the famous rock-hewn churches, carved over 800 years ago.

Accompanied by a slowly building tempo of traditional church drums, metallic sistrum and pilgrims’ clapping, they lead the crowd in an intensely moving musical performance about the birth of Jesus Christ. For though its execution may look different here than in other parts of the world, the focus of Ethiopian Christmas remains the same: to celebrate the birth of a Savior who came to take away the sins of the world, and to bring peace to all mankind.

Sources:

“If the Saint calls you, if you have an open road, then you don’t feel the fire as if it were your enemy,”

Dating back to Pagan times, the Anastenaria is a traditional ritual ritual of fire-walking celebrated in a few places in Northern Greece and in southern Bulgaria, where Greek descendants from Thrace settled in 1923. Every year the Bulgarian and Greek villages if Aghia Eleni near Serres, Langada near Thessaloniki, Kerkini near Serres, some villages on the coast of Evros River and a singular small village near the city of Drama perform this unique annual ritual.

The central figures of the tradition are Saint Constantine and Saint Helen, but all the significant days in this cycle coincide with important days in the Greek Orthodox calendar and are related to various Christian saints.

Along with the fire-walking ritual, the 3-day festival has various processions, music, dancing and an animal sacrifice. On the eve of the feasts of Saints Constantine and Helen, while trance like rhythms of beating drums sound in the background, the Anastenarides take part in dances during which they believe that they are “seized” by the saints, and enter a state of trance. During this trance, they carry the icons of saints Constantine and Helen and dance ecstatically for hours before walking barefoot across hot coals that can reach as hot as 535 degrees Celsius.

The roots of this tradition are seeped in mystery and a bit of controversy as well. The Anastenarides say that the origin of the ritual lies in a fire which took place at Kosti, near the Black Sea in the thirteenth century which set ablaze the church of Saint Constantine. As the empty church burned, the villagers claimed to hear cries coming from the flames and believed that they were the voices of the saints calling out for help. The villagers who braved the flames to rescue them were unharmed, being protected by the saints. Neither the human protectors nor the icons were burned or hurt in any way. This occurrence prompted the annual celebration which the Anastenaria holds to honor their safe delivery.

However, many scholars do not believe this to be the true origin of the Anastenaria rituals. It is largely believed that the ceremony is the survival of an ancient Thracian Dionysian ritual which was later given a superficial Christian interpretation to help receive a better reception from the Greek Orthodox church, which does not support the rituals as they are viewed as pagan. This hasn’t stopped the Anastenarides from celebrating their age old tradition.

The two major events in this cycle are two big festivals, one in January and particularly one in May, dedicated to these two saints. Each of the festivals lasts for 3 days and involves various processions, music and dancing, and an animal sacrifice. The festival culminates with a firewalking ritual, where the participants, carrying the icons of saints Constantine and Helen, dance ecstatically for hours before entering the fire and walking barefoot over the glowing-red coals, unharmed by the fire.

Each village community of Anastenarides is headed by a “group of twelve” who, on the eve of the saints’ day, May 20 Saint Constantine and Saint Helen, gather in the “konaki”, where their holy icons are placed, as well as the “signs” of the saints (semadia), and votive offerings. These are draped with large red kerchiefs (simadia), which are believed to possess the power of the icons.

On the morning of the Saints’ day, May 21, the gather at the konaki and proceed to a well to be blessed with holy water, and sacrifice animals. The rules about the nature of the beasts to be slain are precise, but differ from village to village.

In the konaki they work themselves into a trance-like state through hours of devotional dancing to the music of the Thracian lyre and drum. The main aspect of this festival is at night, when they firewalk. In the evening a fire is lit in an open space, and after dancing for some time in the konaki, the “anastenarides” go to it carrying their ikons. After dancing around it in a circle, individual anastenarides dance over the hot coals as the saint moves them.

They make a huge fire, and when it is down to extremely hot coals, some of them (only some people are “called” to do this) walk and dance on the fire. They believe that during the dance they are “seized” by the saints.

The next day, a ritualistic sacrifice of animals takes place. After lunch the Anastenarides gather again and resume their dancing. A candle is lit from one of the oil lamps in front of the icons, and is used to light a bonfire. When the wood burns, coal is spread down.

Here is a personal account of the experience:

It’s dark outside. The moon hangs in the sky and the soft smell of smoke permeates the warm air as it stings your eyes. Looking down, you notice the glow from burning coals, as hot as 535 degrees C, scattered on the ground below. The trancelike rhythm from the beating drums fills your ears as the Patron Saints Constantine and Helen are honored in the town of Agia Eleni in Northern Greece.

he whole village surrounds you and they share in your moment, as the richness of the surrounding imagery and importance of the ritual consumes the senses. You are in a sublime state of ecstasy as the glowing coals lay before you. But, will you walk across? When Saint Constantine calls you to become a firewalker – you answer – at least if you are one of the Anastenaria.

Initially the Anastenarides dance barefoot around the hot ashes, but when the saints moves them, individuals run across the burning coals. Sometimes devotees kneel down beside the fire and pound the ashes with the palms of their hands. This continues until the ashes are cool.

During the next two days, the Anastenarides proceed around the village visiting each house. On 23 May they conclude with a second dance over the fire, although this one is in private and not for tourists.

The ritual is also performed in January, during the festival of Saint Athanasius, and fire-walking is done indoors.

Sources:

April 16 is the feast day of Saint Bernadette, although in France it is sometimes celebrated on February 18. Saint Bernadette is best known for her visions of the Virgin Mary in 1858 in Lourdes, France and for the healings that have taken place at the location of the visions. St. Bernadette is the patron saint of:

- Physical illness

- Lourdes, France

- Shepherds and shepherdesses

- Poverty

- Those insulted for their faith

- Family

The young shepherdess who saw Our Lady in Lourdes, St. Bernadette, found solace in her suffering by turning her eyes to Our Lord. Suffering today? Pray this prayer from St. Bernadette

“O Jesus, Jesus,” she prayed, “I no longer feel my cross when I think of yours.”

If you’re suffering today, pray this excerpt of one of her prayers:

Let the crucifix be not only in my eyes and on my breast, but in my heart.

O Jesus! Release all my affections and draw them upwards.

Let my crucified heart sink forever into Thine and bury itself in the mysterious wound made by the entry of the lance.”

Saint Bernadette and The Goddess

If you think the visions of Saint Bernadette have no connection to magick and the Goddess think again – here is an alternative version to the traditional story:

On the cold morning of February 11, 1858, there was no wood in the Soubirous home, and no fire to warm them. Bernadette set out with her younger sister Toinette, and a neighbor girl, Jean Abadie, to scrounge in the forest for kindling. Maybe they would get lucky and find a rag or a bone to sell.

Heading out of town, the girls neared the foot of Massabieille, a massive, cliff-top rock formation, within view of the ancient hilltop fortress that served as the traditional landmark of the town. To reach the woods, they had to ford the river Gave at the bottom of the cliff. Bernadette’s mother had warned her not to get her feet wet, for that would surely bring on the asthma, so while the other two girls scampered across the river, Bernadette reluctantly hung back.

According to her own accounts, as she lingered near the banks of the Gave, the girls calling after her as they hurried into the woods, she heard a sound like rushing wind. The sound seemed to be coming from a dark grotto in the rock wall under Massabielle. The noon Angelus bells were ringing from the town. As Bernadette turned to investigate the source of the wind, she saw what looked like a glowing young girl, tiny, white, and smiling brightly. She appeared to be standing above the eglantine, or wild rose, that draped the niche over the entrance to the grotto.

Bernadette rubbed her eyes and looked again. This time, the tiny demoiselle nodded, as if to greet her, and opened her arms, smiling all the while. Bernadette’s initial reaction was fear, but she couldn’t run away. She said she felt like she couldn’t move, but she did manage to instinctively put her hand in her pocket and draw out her rosary for protection. She tried to make the sign of the cross, but found that she couldn’t.

In response, the shining little maiden also produced a rosary, and crossed herself in a gesture of surprising beauty and grace. This time, Bernadette found she could respond, and after crossing herself, she began to feel calmer and a little less overwhelmed. Dropping to her knees, Bernadette began to pray her rosary. The little lady fingered her beads along with her. When they had finished, the tiny thing beckoned her to come closer, but Bernadette was too overawed to move. She then vanished, all smiles and delicate grace, leaving Bernadette to rejoin her companions.

Bernadette’s descriptions of the tiny, white maiden were consistent throughout the course of her visions. The apparition, whom she called aquero, or “that thing” in the local dialect, appeared youthful and girlish. There was nothing particularly matronly or maternal about her. Bernadette repeatedly said that aquero was about the same size as herself, if not a bit smaller. Bernadette was very small for her age. Although she had recently turned fourteen, the combined ravages of illness and malnutrition kept her about the size of an average 10- or 11-year-old. According to Bernadette’s earliest descriptions, aquero looked to be about 12 years old. This is an important distinction, and one that the well-meaning supporters of Lourdes apparently prefer to ignore.

Aquero, according to Bernadette’s initial descriptions, was a jeune fille; a bien mignonette, glowing in a white dress spun of a luxurious, soft, shiny stuff. Her head was covered in a white veil of the same magic fabric, so that only a tiny bit of her hair was revealed in the front. Her eyes were bright blue, and set in a long and very white face. The whole figure shone with a gleaming, white radiance. Around her waist was a blue girdle, which folded in the front and fell almost to the hem of her robe. Her tiny feet, barely visible beneath her robe, were bare, but each was adorned with a single, golden rose. Her rosary gleamed as well, with shining white beads and links of gold.

This costume is quite significant, for in this particular area of the Pyrenees, the locals maintained a tradition of fairy lore that told of the petito damizela in white who still lingered in the forests and grottoes of the region. When Bernadette first called the apparition a petito damizela, which translates as a petite, unmarried young lady, she may have actually been referring to aquero as a Pyrenean fairy woman. These Pyrenean fairies were tiny, enchanting ladies in glowing, white robes. Charming, helpful, and better natured than most fairy folk, they were recognized by their gleaming garments and said to spend much time washing them to snowy whiteness in the fountains outside their grotto homes.

The roses on aquero’s feet were yet another aspect of local fairy lore, as was Bernadette’s reluctance to call her by any name other than “that thing.” According to the tradition, these delightful fairy women sometimes married mortal men, making good wives and housekeepers – for a time. Eventually, the husband would slip up and call his fairy wife by her name, at which point she would disappear back into the fairy world forever.

In the Basque population of the Pyrenees, we have a unique link into the mindset of our most distant ancestors. There is reason to believe the Basques have occupied the Pyrenees region from the remotest antiquity, possibly even to the time of the Cro-Magnon cave painters. The inaccessibility of their mountain fastness kept them relatively isolated from the Indo-European influences that swept the rest of the continent. Consequently, the Basques have retained a unique language and a culture that, while not entirely untainted by foreign contact, still reveals roots reaching down into our most shadowy origins.

Furthermore, the Basques, with their extensive folklore and mythology, are relative latecomers to Roman Catholicism. Religious writers of the 1400 and 1500s continue to speak of the Basques as “gentiles” or “pagans.” The widespread persistence of their ancient beliefs and practices provoked the full wrath of the Spanish Inquisition. The brutal repression of centuries of witch hunts has left its mark, and clearly, some of the tradition that remains is highly adulterated and Christianized, but we can still trace influences extending far back into the Neolithic, and perhaps beyond.

Basque beliefs are rooted in the landscape, in the rugged mountains, the waters, and the caves reaching deep into the earth. They held to that most primitive fundamentalism, the belief in the divinity of the masculine Sun and the feminine Moon. The terms Ost or Eguzki refer to the light of the sun and their god of the firmament. This masculine force, similar to Zeus or Thor, ruled the day and the world of light, but the night belonged to Ilargia, the Moon. Ilargia ruled the hidden, dark side of nature, the underworld of the dead. The Basques were forever fascinated with her mysterious phases and cycles.

However, the Basque people’s deepest and most widespread devotion, long before the arrival of Christianity in the Pyrenees, centered on their female deity, the great goddess who lived in the caves. Her name, perhaps the ultimate irony, was Mari. Devotion to Mari spanned the entire Basque territory, and any respectable hilltop boasted a shrine to Mari, and a statue as well, but the caves remained her favorite habitation.

Within the vast lore and ritual dedicated to her worship, the image of Mari emerges, complex and glorious. She moved like a fireball from mountaintop to mountaintop, trailing wild storms from the subterranean caverns in her wake. She demanded honor and charity from men, punishing those who failed to keep their word or refused to help others. Oddly enough, tradition holds that Mari must only be addressed in the familiar pronoun, putting a unique twist on Bernadette’s surprise at being addressed formally by her aquero. Mari commanded legions of fairy spirits, with varying titles in different locales: the Mairi, or Maide of the mountaintop cromlechs and stone circles, and the fey laminak, often spotted combing their hair in the caverns.

This great and very ancient goddess spawned a vast body of tales and traditions, and the rituals of her devotees in the caves of the Pyrenees kept the Spanish Inquisition busy for years. One of her most vicious persecutors was Juan de Zumarraga, who, in 1528, assisted in the biggest Basque witchhunt. Zumarraga eventually moved on to Mexico, where, as bishop, he persecuted and destroyed the native Aztec culture and religion just as vigorously as he had brutalized his Basque brethren.

One of Mari’s more popular minions is a creature known as Beigorri, a red-haired bull or calf. One of several cattle deities associated with her worship, Beigorri’s chief function is to serve as the guardian of the houses, or shrines, of Mari. Seen in that light, the tales of a magical bovine unearthing a long-lost statue of a female divinity, which then refuses to be worshiped in a Christian sanctuary but instead draws her devotees back to congregate at her wilderness origins, starts to make a certain kind of sense. Perhaps, in these unique Marian traditions, which continue to spring up so freely, even after centuries of repression, we can trace both the reemergence of the Basque Mari, and her conflation, in the aftermath of the Inquisition, into the all-encompassing image of the Christian Mary.

Sources:

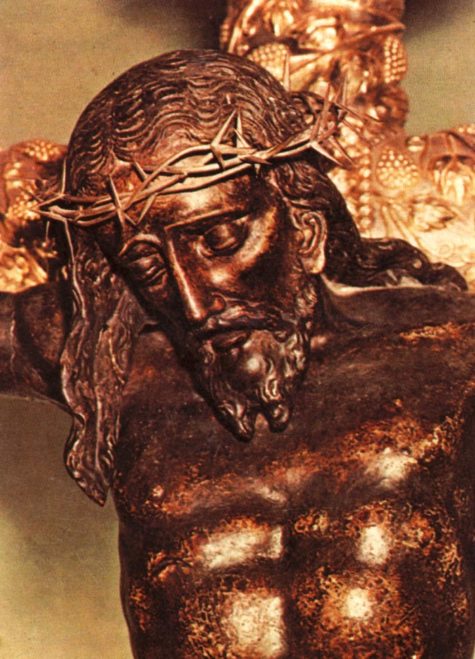

The Black Christ of Esquipulas is a wooden image of Christ now housed in the Cathedral Basilica of Esquipulas in Esquipulas, Guatemala. A lovely Baroque structure painted a gleaming white, the basilica dominates the town’s skyline. Remarkably, it has survived many earthquakes over the centuries with little damage.

The image is known as “black” because over more than 400 years of veneration its wood has acquired a darker hue, although such a name is relatively recent – in the 17th century it was also known as the “Miraculous Lord of Esquipulas” or the “Miraculous Crucifix venerated in the town called Esquipulas”.

The Black Christ is housed in a glass case on the altar at the east end of the basilica. A large statue that depicts Christ suffering on the cross, it is part of a Crucifixion group with Mary Magdalene and St. John.

Pilgrims stand in line along the west side of the church to see El Cristo Negro up close, sometimes waiting for over an hour. After viewing the statue and saying their prayers, pilgrims back away from it on the other side, believing it an offense to turn their back on the holy image.

Tens of thousands of devout Catholics cram into Esquipulas during the annual celebration of the Black Christ which happens on January 15th. They come to pray and ask for help in front of a religious icon which has been credited with miraculously curing Pedro Pardo de Figueroa, the Archbishop of Guatemala, from a serious illness in 1737.

The largest number of pilgrims come from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua and other Central American countries. The January 15th festival is also marked in the United States of America in cities such as Los Angeles, New Jersey and New York with a high Central American population.

Special processions and services are also held on July 21-27, and during Holy Week each year.

History of Esquipulas Basilica

The statue of the Black Christ (El Cristo Negro) was comissioned by Spanish conquistadors for a church in Esquipulas. It was carved in 1594 by Quirio Cataño in Antigua and installed in the church in 1595. By 1603, a miracle had already been attributed to the icon, and it attracted increasing numbers of pilgrims over the years.

The history of the Basilica begins in 1735, when a priest named Father Pedro Pardo de Figueroa experienced a miraculous cure after praying before the statue. When he became Archbishop of Guatemala, he commissioned a beautiful basilica to properly shelter the beloved statue. The church was completed in 1759.

Perhaps an even more impressive miracle is the fact that Esquipulas was the site of a Central American peace summit which laid the groundwork for what became the Guatemalan Peace Accords of 1996 which ended the country’s ghastly 36 year civil war.

The Basilica de Esquipulas is such a major religious site that Pope John Paul II paid a visit in 1996 to mark the 400th anniversary of the church which the Pope is said to have called “the spiritual center of Central America.” In 2009, celebrations were held to mark 250 years since the basilica’s construction.

Sources: Wikipedia, Sacred Destinations and Trans Americas

As usual with big Catholic Feast days, food is involved with the day, with many Catholic families having picnics near their loved ones’ graves. Traditional foods include “Soul Food” — food made of lentils or peas.

Basic Split Pea Soup (serves 4)

- 1 cup chopped onion

- 2 cloves garlic (optional)

- 1 teaspoon vegetable oil or bacon grease

- 1 pound dried split peas

- 1 pound ham bone

- 1 c. chopped ham

- 1 c. chopped carrots (optional)

- salt and pepper to taste

In a medium pot, sauté onions in oil or bacon grease. (Optional: add garlic and sauté until just golden, then remove). Remove from heat and add split peas, ham bone and ham. Add enough water to cover ingredients, and season with salt and pepper.

Cover, and cook until there are no peas left, just a green liquid, 2 hours. (Optional: add carrots halfway through) While it is cooking, check to see if water has evaporated. You may need to add more water as the soup continues to cook.

Once the soup is a green liquid remove from heat, and let stand so it will thicken. Once thickened you may need to heat through to serve. Serve with either sherry or sour cream on top, and with a crusty bread.