Russia

Kupala Night and Ivan Kupala Day is celebrated in Ukraine, Poland, Belarus and Russia from the night of July 6 to the day of July 7 on the Gregorian calendar. This corresponds to June 23 to 24 on the traditional Julian calendar.

The celebration is linked with the summer solstice when nights are the shortest and includes a number of Slavic rituals. This holiday symbolizes the birth of the summer sun – Kupalo.

In the fourth century AD, this day was Christianized and proclaimed the holiday of the birth of John the Baptist. As a result, the pagan feast day “Kupala” was connected with the Christian “Ivan” (Russian for John) which is why the Ukrainian, Belarusian and Russian name of this holiday combines “Ivan” and Kupala which is derived from the Slavic word for bathing.

The two feasts could be connected by reinterpreting John’s baptizing people through full immersion in water. However, the tradition of Kupala predates Christianity. The pagan celebration was adapted and reestablished as one of the native Christian traditions intertwined with local folklore.

And Then It Was Banned

In the XVIII century, there were a number of documents testifying to the fierce struggle of the Church and secular authorities with the Kupala rite.

For example, in 1719 Hetman of Zaporizhzhia Army, Chairman of the Cossack state of the left bank of Ukraine, Ivan Skoropadskyi issued a decree “On parties, fisticuffs, gatherings on the holiday of Ivan Kupala etc.”, which granted the right to physically punish (tie up and beat with sticks) and excommunicate from the Church all participants of Kupala games.

In 1723, Przemysl Cathedral in Bereziv banned dancing and entertainment near the Kupala fire. In 1769, Catherine II issued a decree banning the holiday. And despite all the prohibitions, the pagan nature of folk rituals was strong. The church did not ban the holiday, but it did try to fill it with Christian content.

It is the pagan essence, mysticism, marriage-erotic motifs of Kupala rite that attracted the attention of many researchers and artists. Thanks to public ritual such art masterpieces as the Opera “Ivana Kupala” by S. Pysarevskyi; folklore work of L. Ukrainka “Kupala in Volyn”; the story of M. Gogol “Night of Ivan Kupala”; the film of Yurii Ilienko “Night on Ivan Kupala”; the Folk Opera of Y. Sankovych “When the fern blooms.” The latter during 40 years was banned and only in 2017 its world premiere took place on the stage of the Lviv Opera.

Kupala Today

At the beginning of the twentieth century Kupala rite gradually began to disappear. Today it exists in the “revived”, or rather “introduced” in Soviet times (during the anti-religious struggle) form of staged ceremony.

Although the magical meaning of rituals was leveled, and the celebration gained artistic value, the main pagan ritual actions have reached us – weaving of wreaths by girls and letting them into the water; honoring Kupala tree with dances; kindling the fire and jumping over the fire; ritual bathing; burning or sinking of trees; the burning of sacks of straw or stuffed dolls; the ceremonial dinner.

It is interesting that the name of the holiday, and the ritual fire, and decorated tree are called “Kupalo”, “Kupailo” or “Kupailytsia”. These are also the main elements of the rituals, which are based on the cult of fire, water and vegetation. Rituals symbolize the union of male (fire) and feminine (water) elements, were carried out with the aim of ensuring productivity, health, procreation.

On the territory of Ukraine for many centuries Kupala customs changed and they were not everywhere equally preserved. The majority were saved in Polissia as one of the more archaic zones of the Slavic world.

The holiday is still enthusiastically celebrated by the younger people of Eastern Europe. The night preceding the holiday (Tvorila night) is considered the night for “good humor” mischiefs (which sometimes would raise the concern of law enforcement agencies).

On Ivan Kupala day itself, children engage in water fights and perform pranks, mostly involving pouring water over people. Many of the rites related to this holiday are connected with the role of water in fertility and ritual purification.

According to ancient traditions, Ivan Kupala is the festival of the sun, and the most important role in mystical rites belongs to the power of fire. Our ancestors believed that the fire is the sun-embryo in the womb. Therefore, in the Kupala night taken to jump over the fire.

On Kupala day, young people jump over the flames of bonfires in a ritual test of bravery and faith. First, the oldest of the young men jumped over the fire.

For the highest jumpers it predicted a good harvest and prosperity for his family. Then pairs would jump, traditionally it would be a boy and a girl, but I assume that in some areas it’s permissible for pairs of any kind to take the jump together. If the couple is successful in their jump over the fire – they will certainly marry. The failure of a couple in love to complete the jump, while holding hands, is a sign of their destined separation. And anyone entering the flames during their jump can expect trouble

On the evening of July 6, unmarried girls take wreaths they have woven and throw them into the water. Unmarried men then try to grab the one belonging to the girl they are interested in. If you snag a wreath, the girl who made it will be expected to kiss you and the two of you will be paired up for the evening.

Girls may also float wreaths of flowers (often lit with candles) on rivers, in an attempt to gain foresight into their romantic relationships based from the flow patterns of the flowers on the river.

When the fun subsides, many people light candles from the hearth on pre-prepared wreath baskets and go to the river to put them on the water and thus honor their ancestors.

There is an ancient Kupala belief that the eve of Ivan Kupala is the only time of the year when ferns bloom. Prosperity, luck, discernment, and power befall whom ever finds a fern flower. Therefore, on that night, village folk roam through the forests in search of magical herbs, and especially, the elusive fern flower.

Traditionally, unmarried women, signified by the garlands in their hair, are the first to enter the forest. They are followed by young men. Therefore, the quest to find herbs and the fern flower may lead to the blooming of relationships between pairs within the forest.

It is to be noted, however, that ferns are not angiosperms (flowering plants), and instead reproduce by spores; they cannot flower.

In Gogol’s story The Eve of Ivan Kupala a young man finds the fantastical fern-flower, but is cursed by it. Gogol’s tale may have been the stimulus for Modest Mussorgsky to compose his tone poem Night on Bald Mountain, adapted by Yuri Ilyenko into a film of the same name.

Sources:

Saint George’s Day is celebrated on April 23, the traditionally accepted date of the saint’s death in AD 303. For those Eastern Orthodox Churches which use the Julian calendar, this date currently falls on the day of 6 May of the Gregorian calendar. In Turkish culture the day is known as Hıdırellez or Xıdır Nəbi and is symbolic of spring renewal.

It is also believed to be a magical day when all evil spells can be broken. It was believed that the saint helps the crops to grow and blesses the morning dew, so early in the morning they walked in the pastures and meadows and collected dew, washed their face, hands and feet in it for good luck and even in some rural parts of Bulgaria it was a custom to roll in it naked.

In Romania, people celebrate St. George – ‘Sfantul Gheorghe’ – and in certain regions, including Bucovina, people will still plant cut willow branches in freshly cut earth and place them at the entrances to their homes.

Many Christian denominations in Syria celebrate St George’s Day, especially in the Homs Governorate. They do this by dressing small children as dragons and chasing them through the streets whilst beating them with clubs and batons. It is a very special time of year, after the beatings folks will enjoy a sit down dinner and dancing.

Saint George’s Day is the feast day of Saint George as celebrated by various Christian Churches and by the several nations, kingdoms, countries, and cities of which Saint George is the patron saint.

Since Easter often falls close to Saint George’s Day, the church celebration of the feast may be moved to accommodate the Easter Festivities. Similarly, the Eastern Orthodox celebration of the feast moves accordingly to the first Monday after Easter or, as it is sometimes called, to the Monday of Bright Week.

Some Orthodox Churches have additional feasts dedicated to St George. The country of Georgia celebrates the feast of St. George on April 23, and, more prominently, November 10 (Julian calendar), which currently fall on May 6 and November 23 (Gregorian calendar), respectively.

St George’s Day was a major feast and national holiday in England on a par with Christmas from the early 15th century. The Cross of St. George was flown in 1497 by John Cabot on his voyage to discover Newfoundland and later by Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh. In 1620 it was the flag that was flown on the foremast of the Mayflower when the Pilgrim Fathers arrived in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

St George’s Day was a major feast and national holiday in England on a par with Christmas from the early 15th century. The Cross of St. George was flown in 1497 by John Cabot on his voyage to discover Newfoundland and later by Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh. In 1620 it was the flag that was flown on the foremast of the Mayflower when the Pilgrim Fathers arrived in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

The tradition of celebration St George’s day had waned by the end of the 18th century after the union of England and Scotland. Nevertheless, the link with St. George continues today, for example Salisbury holds an annual St. George’s Day pageant, the origins of which are believed to go back to the 13th century. In recent years the popularity of St. George’s Day appears to be increasing gradually. Today, St. George’s day may be celebrated with anything English including morris dancing and Punch and Judy shows.

A traditional custom on St George’s day is to wear a red rose in one’s lapel, though this is no longer widely practiced. Another custom is to fly or adorn the St George’s Cross flag in some way: pubs in particular can be seen on April 23 festooned with garlands of St George’s crosses. It is customary for the hymn “Jerusalem” to be sung in cathedrals, churches and chapels on St George’s Day, or on the Sunday closest to it. Traditional English food and drink may be consumed.

In the Valencian city of Alcoi, Saint George’s Day is commemorated as a thanksgiving celebration for the proclaimed aid the Saint provided to the Christian troops fighting the Muslims in the siege of the city. Its citizens commemorate the day with a festivity in which thousands of people parade in medieval costumes, forming two “armies” of Moors and Christians and re-enacting the siege that gave the city to the Christians.

The Serbian St George’s Day is called Đurđevdan and is celebrated on 6 May every year, as the Serbian Orthodox Church uses the Julian, Old Style calendar. Đurđevdan is also celebrated by both Orthodox and Muslim Romani and Muslim Gorani. Đurđevdan is celebrated, especially, in the areas of Raška in Serbia, and is marked by morning picnics, music, and folk dances.

In Russia, St George’s Day (Гергьовден, Gergyovden) is a public holiday that takes place on 6 May each year. It is possibly the most celebrated name day in the country. A common ritual is to prepare and eat a whole lamb, which is an ancient practice possibly related to Slavic pagan sacrificial traditions and the fact that St George is the patron saint of shepherds.

A Protective Blessing Ritual for Saint George’s Day:

In many communities, Saint George’s Day was the day animals were lead out into the field, thus protective, blessing rituals abound. Here’s one:

- Lead all healthy animals three times around the perimeter of their field, barn or home, always in a sunwise direction.

- The person leading the parade carries a lit torch.

- The person bringing up the rear holds an open padlock in one hand, the key in the other hand.

- After the third round, the animals are lead back into the barn.

- Turn the key in the lock.

- Throw the key into a river or stream, while preserving the now permanently locked padlock.

Dragons and Dragon’s Blood:

St. George is credited with having slain a fearsome dragon to save the life of a virgin. The Dragon means different things to different peoples. In some medieval traditions it is linked with the devil or Satan, hence the carvings and windows depicting St George, (or sometimes St Michael), slaying one.

But the Dragon has far older associations in which it represents the life force of the land. In the Craft we often refer to the Earth Dragon, a great coiled beast who sleeps within the Earth and who can be called upon to work healing for the planet. The Earth Dragon is often invoked in cases of potential ecological danger. King Arthur’s father was named Uther Pendragon, and it is thought that his name shows that he was a defender of the land. The Dragon is a symbol of Wales and appears on the country’s flag.

Dragon’s blood is not the blood of some luckless lizard, but the resin of the palm calimus draco. Magically it is used for spells of protection, exorcism and sexual potency. Added to incenses it increases their potency and drives away all negativity. On its own Dragon’s blood can be burnt at an open window to secure a lover’s return, and a piece of the resin placed under the mattress is said to cure impotence. In the past Dragon’s Blood was used medicinally to cure diarrhoea, dysentery and even syphilis. Like many other resins it is also used to stop bleeding wounds.

Sources:

Blins or blini were symbolically considered by early Slavic peoples in pre-Christian times as a symbol of the sun, due to their round form. They were traditionally prepared at the end of winter to honor the rebirth of the new sun. This tradition was adopted by the Orthodox church (Shrovetide, Butter Week, or Maslenitsa) and is carried on to the present day. Blini were also served at wakes to commemorate the recently deceased.

Traditional Russian blini are made with yeasted batter, which is left to rise and then diluted with cold or boiling water or milk. When diluted with boiling water, they are referred to as zavarniye blini. The blini are then baked in a traditional Russian oven. The process of cooking blini is still referred to as baking in Russian, even though these days they are almost universally pan-fried, like pancakes.

French crêpes made from unyeasted batter (usually made of flour, milk, and eggs) are also not uncommon in Russia, where they are called blinchiki and are considered to be an imported dish. All kinds of flour may be used for making blini: from wheat and buckwheat to oatmeal and millet, although wheat is currently the most popular.

What follows is a recipe for traditional Russian blini from RusCuisine. These pancakes are served with different dressings – most popular are sour cream, jam, syrup, red caviar, salmon, cottage cheese and others.

Ingredients:

- 3 1/2 c All-purpose flour

- 3 tb Water warm 105-F degrees

- 1 1/2 pk Yeast dry

- 3 3/4 c Milk warm 105-F degrees

- 1 tb Sugar

- 1/2 c Heavy cream

- 1 Egg white

- 2 Egg yolks

- 1 ts Salt

- 4 tb Butter unsalted melted and cooled until just warm

Take 1 tablespoon of the flour, the warm water, 1 teaspoon of the sugar, and the yeast and mix together in a small bowl. Cover and set in a warm place for 15 minutes. Mix in a large bowl the the 1 1/2 teaspoons of sugar, flour, milk, the yeast mixture and salt. Beat by hand for 4 minutes. Cover and set in a warm place for 1 hour.

Mix the egg yolks and remaining sugar and add to the natter along with the butter and beat with an electric mixer for 3 minutes or by hand for 8 minutes. Whip the egg white separately and whip the cream as well until very stiff. Fold in the cream then the egg white making sure to mix well. Cover again and place in a warm place for 45 minutes.

Grease the skillet with butter, place 2 tablespoons of batter in the center of the skillet, (at this point you may add any of the flavor garnishes that you wish or none at all) cook for 1 minute, turn the bliny over, and cook for 35 seconds, and serve smothered in sweet butter.

The last day of the Russian Butter Festival, also called Maslenitsa , or Cheesefare Week is called “Forgiveness Sunday.” Relatives and friends ask each other for forgiveness and might offer them small presents.

At Vespers on Sunday evening, people may make a poklon (bow) before one another and ask forgiveness. Another name for Forgiveness Sunday is “Cheesefare Sunday”, because for devout Orthodox Christians it is the last day on which dairy products may be consumed until Easter. Fish, wine and olive oil will also be forbidden on most days of Great Lent.

The day following Cheesefare Sunday is called Clean Monday, because people have confessed their sins, asked forgiveness, and begun Great Lent with a clean slate.

Here is a deeper explanation of the Catholic symbolism of this day:

Before we enter the Lenten fast, we are reminded that there can be no true fast, no genuine repentance, no reconciliation with God, unless we are at the same time reconciled with one another. A fast without mutual love is the fast of demons. We do not travel the road of Lent as isolated individuals but as members of a family. Our asceticism and fasting should not separate us from others, but should link us to them with ever-stronger bonds.

Found at: Wikipedia and other sources

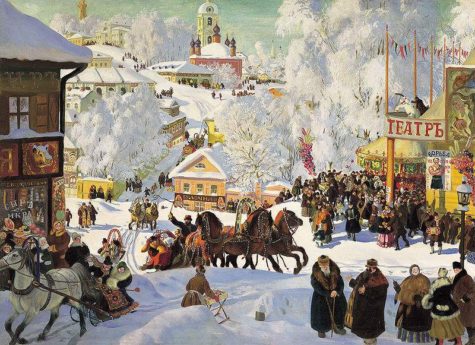

According to archeological evidence from 2nd century A.D. Maslenitsa may be the oldest surviving Slavic holiday. Maslenitsa has its origins in the pagan tradition. In Slavic mythology, Maslenitsa is a sun-festival, personified by the ancient god Volos, and a celebration of the imminent end of the winter. In the Christian tradition, Maslenitsa is the last week before the onset of Great Lent.

During the week of Maslenitsa, meat is already forbidden to Orthodox Christians, and it is the last week during which eggs, milk, cheese and other dairy products are permitted, leading to its name of “Cheese-fare week” or “Crepe week”. The most characteristic food of Maslenitsa is bliny thin pancakes or crepes, made from the rich foods still allowed by the Orthodox tradition that week: butter, eggs and milk. Here’s a recipe: Classic Krasnye Blini

Since Lent excludes parties, secular music, dancing and other distractions from spiritual life, Maslenitsa represents the last chance to take part in social activities that are not appropriate during the more prayerful, sober and introspective Lenten season.

In some regions, each day of Maslenitsa had its traditional activity:

Monday:

Monday may be the welcoming of “Lady Maslenitsa”. The community builds the Maslenitsa effigy out of straw (из соломы), decorated with pieces of rags, and fixed to a pole formerly known as Kostroma. It is paraded around and the first pancakes may be made and offered to the poor.

Tuesday:

On Tuesday, young men might search for a fiancée to marry after lent.

Wednesday:

On Wednesday sons-in-law may visit their mother-in-law who has prepared pancakes and invited other guests for a party.

Thursday:

Thursday may be devoted to outdoor activities. People may take off work and spend the day sledding, ice skating, snowball fights and with sleigh rides.

Friday:

On Friday sons-in-law may invite their mothers-in-law for dinner.

Saturday: Saturday may be a gathering of a young wife with her sisters-in-law to work on a good relationship.

Sunday:

Relatives and friends ask each other for forgiveness and might offer them small presents. As the culmination of the celebration people gather to “strip Lady Maslenitsa of her finery” and burn her in a bonfire. Left-over pancakes may also be thrown into the fire and Lady Maslenitsa’s ashes are buried in the snow to “fertilize the crops”.

Found at: Wikipedia

Maslyanitsa means butter in Russian, and it is also the name of the festival that says goodbye to winter and welcomes summer. From Moscow to St. Petersberg, Russians celebrate Butter Week just before their Lent fast days. The dates vary falling sometime in February or March. (In 2018, this festival begins on Feb 12).

During Lent, meat, fish, dairy products and eggs are forbidden. Furthermore, Lent also excludes parties, secular music, dancing and other distractions from the spiritual life. Thus, Maslenitsa represents the last chance to partake of dairy products and those social activities that are not appropriate during the more prayerful, sober and introspective Lenten season.

Monday is the high point of celebration, when people cook pancakes, or blini, served with honey, caviar, fresh cream and butter. The more butter there is, the hotter the sun is expected to be in the coming summer.

The most characteristic food of Maslenitsa is bliny (pancakes). Round and golden, they are made from the rich foods still allowed by the Orthodox tradition: butter, eggs and milk. Here’s an authentic traditional recipe: Classic Krasnye Blini.

Maslenitsa activities also include snowball fights, sledding, riding on swings and plenty of sleigh rides. In some regions, each day of Maslenitsa had its traditional activity: one day for sleigh-riding, another for the sons-in-law to visit their parents-in-law, another day for visiting the godparents, etc. The mascot of the celebration is usually a brightly dressed straw effigy of Lady Shrovetide, formerly known as Kostroma.

As the culmination of the celebration, on Sunday evening, Lady Maslenitsa is stripped of her finery and put to the flames of a bonfire. Any remaining blintzes (pancakes) are also thrown on the fire and Lady Maslenitsa’s ashes are buried in the snow “fertilize the crops”.

The last day of Butter Week is called “Forgiveness Sunday,” At Vespers on Sunday evening, all the people make a poklon (prostration) before one another and ask forgiveness, and thus Great Lent begins in the spirit of reconciliation and Christian love. The day following Forgiveness Sunday is called Clean Monday, because everyone has confessed their sins, asked forgiveness, and begun Great Lent with a clean slate.

Found at: Wikipedia

Christmas in Russia is celebrated on 7 January and marks the birthday of Jesus Christ. Christmas is mainly a religious event in Russia. On Christmas Eve (6 January), there are several long services, including the Royal Hours and Vespers combined with the Divine Liturgy. The family will then return home for the traditional Christmas Eve “Holy Supper”, which consists of 12 dishes, one to honor each of the Twelve Apostles. Devout families will then return to church for the “всенощная” All Night Vigil. Then again, on Christmas Morning, for the “заутренняя” Divine Liturgy of the Nativity. Since 1992 Christmas has become a national holiday in Russia, as part of the ten-day holiday at the start of every new year.

During the early-mid Soviet period, religious celebrations were discouraged by the official state policy of atheism until 1936. Christmas tree and related celebrations were gradually eradicated after the October Revolution. In 1935, in a surprising turn of state politics, the Christmas tradition was adopted as part of the secular New Year celebration. These include the decoration of a tree, or “ёлка” (spruce), festive decorations and family gatherings, the visit by gift-giving “Ded Moroz” (Дед Мороз “Grandfather Frost“) and his granddaughter, “Snegurochka” (Снегурочка “The Snowmaiden”).

Snowflake, a variation of The Snowmiden stories can be found here: Snowflake.

Principal dishes on the Christmas table in old Russia included a variety of pork (roasted pig), stuffed pig’s head, roasted meat chunks, jelly (kholodets), and aspic. Christmas dinner also included many other meats: goose with apples, sour cream hare, venison, lamb, whole fish, etc. The abundance of lumpy fried and baked meats, whole baked chicken, and fish on the festive table was associated with features of the Russian oven, which allowed successful preparation of large portions.

Finely sliced meat and pork was cooked in pots with semi-traditional porridge. Pies were indispensable dishes for Christmas, as well as other holidays, and included both closed and open style pirogi (pirozhki, vatrushkas, coulibiacs, kurnik, boats, saechki, shangi), kalachi, cooked casseroles, and blini. Fillings of every flavor were included (herbal, vegetable, fruit, mushrooms, meat, fish, cheese, mixed).

Sweet dishes served on the Russian Christmas table included berries, fruit, candy, cakes, angel wings, biscuits, honey. Beverages included drinking broths (kompot and sweet soups, sbiten), kissel, and, from the beginning of the 18th century, Chinese tea.

Source: Wikipedia

The first full moon in November is the feast day of Baba Yaga. Baba Yaga’s themes are the harvest, rest, providence, thankfulness and cycles. Her symbols are corn sheaves, wreaths of wheat, corn, rye and wild flowers. This Lithuanian/Russian Goddess of regeneration, Baba Yaga is typically represented as the last sheaf of corn in today’s festivities – Obzinky. As both young and old, She reawakens in us an awareness of time’s ever-moving wheel, the seasons and the significance of both to our Goddess-centered magic.

- More about her here: Baba Yaga

Follow with the tradition and make or buy a wreath or bundle of corn shucks or other harvest items. Keep this in your home to inspire Baba Yaga’s providence and prosperity for everyone who lives there.

For breakfast, consume a multigrain cereal, rye bagels or wheat toast. Keep a few pieces of dried grains or toasted breads with you. This way you’ll internalize Baba Yaga’s timeliness for coping with your day more effectively and efficiently, and you’ll carry Her providence with you no matter the circumstances.

Feast on newly harvested foods, thanking Baba Yaga as the maker of your meal. Make sure you put away one piece of corn that will not be consumed today, however. Dry it and hang it up to ensure a good harvest the next year, for your garden, pocketbook or heart.

Finally, decorate your home or office with a handful of wild flowers (even dandelions qualify). Baba Yaga’s energy will follow them and you to where it’s most needed.”

Source: 365 Goddess