The winter solstice (or hibernal solstice), also known as midwinter, is an astronomical phenomenon marking the day with the shortest period of daylight and the longest night of the year. In the Northern Hemisphere this is the December solstice and in the Southern Hemisphere this is the June solstice.

The Winter Solstice has been celebrated for millennia by cultures and religions all over the world. Many modern pagan religions are descended in spirit from the ancient pre-Christian religions of Europe and the British Isles, and honor the divine as manifest in nature, the turning of the seasons, and the powerfully cyclical nature of life.

Worldwide, interpretation of the event has varied across cultures, but many have held a recognition of rebirth, involving holidays, festivals, gatherings, rituals or other celebrations around that time.

Most pagan religions are polytheistic, honoring both male and female deities, which are seen by some as two aspects of one non-gendered god, by others as two separate by complementing beings, and by others as entire pantheons of gods and goddesses.

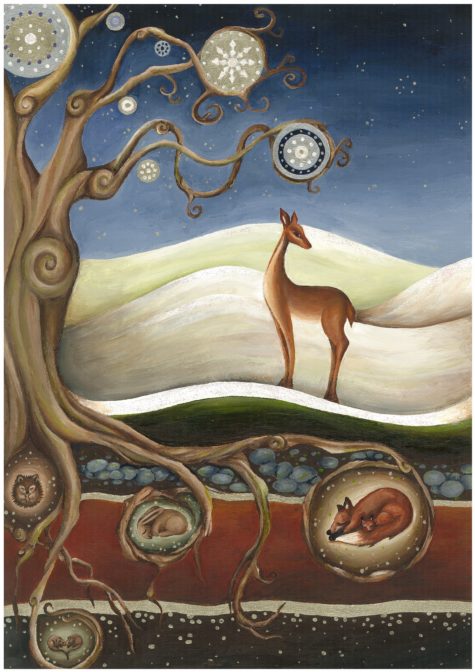

It is common for the male god(s) to be represented in the sun, the stars, in summer grain, and in the wild animals and places of the earth. The stag is a powerful representation of the male god, who is often called “the horned god.”

The Goddess is most often represented in the earth as a planet, the moon, the oceans, and in the domestic animals and the cultivated areas of the earth.

In many pagan traditions the Winter Solstice symbolizes the rebirth of the sun god from his mother, the earth goddess. The Winter Solstice is only one of eight seasonal holidays celebrated by modern pagans.

Historical Notes

The solstice may have been a special moment of the annual cycle for some cultures even during neolithic times. Astronomical events were often used to guide activities such as the mating of animals, the sowing of crops and the monitoring of winter reserves of food.

Many cultural mythologies and traditions are derived from this. This is attested by physical remains in the layouts of late Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeological sites, such as Stonehenge in England and Newgrange in Ireland.

The primary axes of both of these monuments seem to have been carefully aligned on a sight-line pointing to the winter solstice sunrise (Newgrange) and the winter solstice sunset (Stonehenge). It is significant that at Stonehenge the Great Trilithon was oriented outwards from the middle of the monument, i.e. its smooth flat face was turned towards the midwinter Sun.

The winter solstice was immensely important because the people were economically dependent on monitoring the progress of the seasons. Starvation was common during the first months of the winter, January to April (northern hemisphere) or July to October (southern hemisphere), also known as “the famine months”.

In temperate climates, the midwinter festival was the last feast celebration, before deep winter began. Most cattle were slaughtered so they would not have to be fed during the winter, so it was almost the only time of year when a plentiful supply of fresh meat was available. The majority of wine and beer made during the year was finally fermented and ready for drinking at this time.

The concentration of the observances were not always on the day commencing at midnight or at dawn, but at the beginning of the pagan day, which in many cultures fell on the previous eve. Because the event was seen as the reversal of the Sun’s ebbing presence in the sky, concepts of the birth or rebirth of sun gods have been common and, in cultures which used cyclic calendars based on the winter solstice, the “year as reborn” was celebrated with reference to life-death-rebirth deities or “new beginnings” such as Hogmanay’s redding, a New Year cleaning tradition. Also “reversal” is yet another frequent theme, as in Saturnalia’s slave and master reversals.

A Winter Solstice reading:

This is the night of the Solstice, the longest night of the year. Now darkness triumphs, yet gives way and changes into light. The breath of Nature is suspended: all waits while within the Cauldron, the Dark King is transformed into the infant light. We watch for the coming of Dawn, when the great Mother again gives birth to the Divine child Sun, who is bringer of hope and the promise of summer. This is the stillness behind motion, when time itself stops; the center, which is also the circumference of all. We are awake in the Night. We turn the Wheel to bring the Light. We call the sun from the womb of night.

Celebrating the Winter Solstice

At the Winter Solstice we celebrate by bringing warmth, light and cheerfulness into this dark time of the year. Holidays such as this have their origins as “holy days”. They are the way human beings mark the sacred times in the yearly cycle of life.

On this shortest day of the year, the sun is at its lowest and weakest, a pivot point from which the light will grow stronger and brighter. This is the pivot point of the year. The Romans called it Dies Natalis Invicti Solis, the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun.

A simple way to celebrate this day is with a small candle lighting ceremony. The purpose being to celebrate this time of renewal in our lives, to give thanksgiving for the past and the present and to offer a blessing for the year to come.

- How to:

Create a small sacred space. Decorate it in a way that feels cheerful, warm, and bright. In the center place a white candle. As the sun sets on this day, light the candle, and say a few words about bringing the light forth in your life, in the lives of your family and loved ones in the coming year. Either allow the candle to burn out of it’s own accord, or relight it every evening until Jan 1st.

From Wikipedia and other sources

Krazelna: Day of Hekate

Krazelna: Day of Hekate

Krazelna: Day of Hekate

Rachel V Perry: Emancipation Day

Rachel: The Nemesia

Leave a Reply