Bonfires

Here’s how they celebrate Beltane in Edinburgh!

Enjoy!

First organized in the 1980’s, the Beltane Fire Festival has become a popular festival in Edinburgh. Here we have photos of the Beltane Fire Society celebrating Spring and the coming of summer. This lively procession celebrates the ending of winter and is a revival of the ancient Celtic festival of Beltane which is the Gaelic name for the month of May. More about Beltane can be found here: Beltane

Also called The Parilia, this festival is dedicated to the Another festival to Pales, goddess of herds. In ancient Roman religion, Pales was a deity of shepherds, flocks and livestock. Regarded as male by some sources and female by others, Pales can be either singular or plural in Latin, and refers at least once to a pair of deities.

During these festivals, ritualistic cleansing of sheep/cattle pens and animals would take place. There are two dates for this festival, one is April 21, and the other on July 7. The festival in April was for smaller livestock, while the one in July was for larger animals.

The festival, basically a purification rite for herdsmen, beasts, and stalls, was at first celebrated by the early kings of Rome, later by the pontifex maximus, or chief priest.

The Vestal Virgins opened the festival by distributing straw and the ashes and blood of sacrificial animals. Ritual cleaning, anointment, and adornment of herds and stalls followed, together with offerings of simple foods.

Shepherds swept out the pens and smudged the animals and pens with burning sulfur. In the evening, the animals were sprinkled with water, and their pens were decorated with garlands. Fires were started, and in were thrown olives, horse blood, beanstalks without pods, and the ashes from the Fordicalia fires. Men and beasts jumped over the fire three times to purify themselves further, and to bring them protection from anything that might harm them (wolves, sickness, starvation, etc.). After the animals were put back into their pens the shepherds would offer non-blood sacrifices of grain, cake millet, and warm milk to Pales.

Another description of this Festival from Nova Roma is as follows:

The Parilia is both an ancient agricultural festival sacred to Pales and the birthday of Eternal Roma Herself. The sheep-fold is decorated with greenery and a wreath placed on its entrance. At first light the fold is scrubbed and swept, and the sheep themselves are cleansed with sulfur smoke. A fire is made of olive and pine wood, into which laurel branches are thrown; their crackling is a good omen. Offerings are made of cakes of millet, other food, and pails of milk.

A prayer is then said four times to Pales (while facing east), seeking protection and prosperity for the shepherd and his flocks, forgiveness for unintentional transgressions against Pales, and the warding off of wolves and disease. The shepherd then washes his hands with dew. Milk and wine is heated and drunk, and then he leaps through a bonfire (and possibly his flocks as well).

Day of Pales Ritual

From the Pagan Book of Hours, we have a modern day ritual for the Day of Pales.

- Color: Sand-colored

- Element: Earth

- Altar: Upon a sand-colored cloth set a man’s right shoe and a woman’s left shoe, side by side, with a shepherd’s crook between them, and small figures of goats and sheep.

- Offerings: Work in the barn with livestock. Do some chore or work-task that you were taught was inappropriate for your gender.

- Daily Meal: Goat. Lamb or mutton. Coarse bread. Soup or stew. Greens.

Invocation to Pales

Hail, Keeper of Flocks and Herds,

Ass-headed god/dess, you who are

Both male and female,

Both god and peasant,

Patron of those who must dirty their hands,

Beloved of the working man and woman,

You who do not play favorites,

Trickster who loves a good joke,

Lord of the dry land between the rivers

Where your flocks graze on scrub

And the people’s blood flows like water

In their everlasting feud,

Come to us and show us life

Through your crooked ass eyes!

Hail, Keeper of Flocks and Herds,

Lady/Lord of the crook and sandals,

You show us that roles

Are meant to be transgressed,

That work can be radical,

That being bound to the labor of the Earth

Does not have to make one heavy.

We need your humor, divine ass!

We need your braying laughter to echo

Over the desert and through our hearts,

And to watch you tip the balance of power

Like a child tips an apple cart.

Hail, Keeper of Flocks and Herds!

(After the invocation, go to the barn, or to a local farm. Hoofed livestock should be given treats on this day, in honor of Pales.)

The Easter Fire is a custom of pagan origin spread all over Europe. It is a symbol of victory, the victory of beautiful and sunny spring over the cold days of winter.

On Holy Saturday or Easter Sunday, in rare occasions also on Easter Monday, large fires are lit at dusk in numerous sections of Northwestern Europe. These regions include Denmark, parts of Sweden as well as in Finland, Northern Germany, Switzerland, and Austria.

The fire is lit usually on the top of the mountains – Easter mountain, Osterberg – and it is obtained from wood by friction. In Germany, the Easter fire is created by gathering all the Christmas trees and burning them into a huge fire, a sign for everyone to leave behind winter and prepare for spring.

Though not documented before the 16th century, the custom presumably is based on Saxon, pre-Christian traditions, that are still performed each year. There are several explanations of the meaning of these fires. The Saxons believed that around the time of Easter, Spring becomes victorious over Winter. The fires were to help chase the darkness and winter away. It was also a symbol of fertility, which works in a literal sense in that the ashes were scattered over the meadows and thereby fertilized the soil.

The pre-Christian meaning of Easter fires is hardly experienced anymore. Nowadays they are meant to bring the community together, which guarantees a pleasant night combined with the consumption of beer, mulled wine or liquor, and snacks.

Source: Wikipedia

This is the name given to two festivals held in ancient Boeotia, which was a part of Greece, in honor of the reconciliation of Hera and Zeus. The dates of these festivals are somewhat nebulous and varied from place to place and year to year. One source cites March 10th.

The story:

According to the myth, Hera and Zeus quarreled and Hera went away to Euboea and refused to return to his bed. To trick her into coming back and on the advice of Cithaeron, Zeus dressed up a carved oak-trunk to resemble a bride and let it be known that he planned to marry Plataea, the daughter of Asopus. Hera was so angry she tore the clothes from the statue, discovered the deception, and was so pleased that the two were reconciled.

The festivities:

The Lesser Daedala (Δαίδαλα μικρά) was held every four to six years. The people of Plataea went to an ancient oak grove and exposed pieces of cooked meat to ravens, attentively watching upon which tree any of the birds, after taking a piece of meat, would settle. Out of this tree they carved an image, and having it dressed as a bride, they set it on a bullock cart with a bridesmaid beside it. The image seems then to have been drawn to the bank of the river Asopus and back to the town, attended by a cheering crowd.

After fourteen of these cycles (approx.59 or 60 years), the Greater Daedala (Δαίδαλα μεγάλα) was held, and all Boeotia joined in the celebration. At its start one wooden figure was chosen from the many that had accumulated through the years and designated the “bride”. The wooden figure was prepared as a bride for a wedding, ritually bathed in the Asopus, adorned and raised on a wagon with an attendant. This wagon led a procession of wains carrying the accumulated daedala (all the other images that had been created over the years) up to the summit of Mount Kithairon, where a wooden sacrificial altar was erected out of square pieces of wood.

This was covered with a quantity of dry wood, and the towns, persons of rank, and other wealthy individuals, offered each a heifer to Hera and a bull to Zeus with plenty of wine and incense, while at the same time all of the daedala were placed upon the altar. For those who did not possess sufficient means, it was customary to offer small sheep, but all these offerings were immolated in a hecatomb in the same manner as those of the wealthier persons. The fire consumed both offerings and altar

An ancient account of myth behind the festival is related by Pausanias:

“Hera, they say, was for some reason or other angry with Zeus, and had retreated to Euboia. Zeus, failing to make her change her mind, visited Kithairon, at that time despot in Plataea, who surpassed all men for his cleverness. So he ordered Zeus to make an image of wood, and to carry it, wrapped up, in a bullock wagon, and to say that he was celebrating his marriage with Plataia, the daughter of Asopus. So Zeus followed the advice of Kithairon.

Hera heard the news at once, and at once appeared on the scene. But when she came near the wagon and tore away the dress from the image, she was pleased at the deceit, on finding it a wooden image and not a bride, and was reconciled to Zeus. To commemorate this reconciliation they celebrate a festival called Daidala, because the men of old time gave the name of daidala to wooden images… the Plataeans hold the festival of the Daidala every six years, according to the local guide, but really at a shorter interval.

I wanted very much to calculate exactly the interval between one Daedala and the next, but I was unable to do so. In this way they celebrate the feast.”

Found at Wikipedia

Up Helly Aa refers to any of a variety of fire festivals held in Shetland, in Scotland, annually in the middle of winter to mark the end of the yule season and celebrate the arrival of the Vikings. Traditionally held on the last Tuesday in January, the festival involves a procession of up to a thousand guizers in Lerwick and considerably lower numbers in the more rural festivals, formed into squads who march through the town or village in a variety of themed costumes.

The current Lerwick celebration grew out of the older yule tradition of tar barreling which took place at Christmas and New Year as well as Up Helly-Aa. After the abolition of tar barreling, permission was eventually obtained for torch processions. The first yule torch procession took place in 1876. The first torch celebration on Up Helly-Aa day took place in 1881. The following year the torch lit procession was significantly enhanced and institutionalized through a request by a Lerwick civic body to hold another Up Helly-Aa torch procession for the visit of the Duke of Edinburgh. The first galley was burned in 1889.

There is a main guizer who is dubbed the “Jarl”. There is a committee which you must be part of for fifteen years before you can be a jarl, and only one person is elected to this committee each year.

The procession culminates in the torches being thrown into a replica Viking longship or galley. The event happens all over Shetland, but it is only the Lerwick galley which is not sent seaward. Everywhere else, the galley is sent seabound, in an echo of legendary Viking sea burials.

After the procession, the squads visit local halls (including schools, sports facilities and hotels), where private parties are held. At each hall, each squad performs its act, which may be a send-up of a popular TV show or film, a skit on local events, or singing or dancing, usually in flamboyant costume.

Due to the often-flamboyant costumes and the large quantity of males dressing up as females (Traditionally, the Capital festival does not permit women to partake in the squads) in the Lerwick festival, it has earned the joke name ‘Transvestite Tuesday’. The photos below show a few examples of the festival’s highlights.

Source: Wikipedia

Official Website: Up Helly Aa

Poseidon was once worshiped in every part of Greece as a God of general importance to the community. In ancient Greece, the feast day in his honor was widely celebrated at the beginning of the winter.

POSEIDO′NIA (ποσειδώνια), a festival held every year in Aegina in honour of Poseidon. It seems to have been celebrated by all the inhabitants of the island, as Athenaeus calls it a panegyris, and mentions that during one celebration Phryne, the celebrated hetaera, walked naked into the sea in the presence of the assembled Greeks. This was possibly because in Greek mythology, the sea god Poseidon is one of the most lascivious of the gods, producing more offspring than other note worthily randy gods.

Greek calendars vary from place to place, but in Athens and other parts of ancient Greece, there is a month that corresponds to roughly December/January that is named Poseideon for the sea-god Poseidon. The month of Poseidonia’s most anticipated and most important festival is the feast of the Poseidonia, a winter festival in honor of Poseidon. Since Poseidon is a sea god it is curious that his festival would be held during the time the Greeks were least likely to set sail.

It was celebrated with the pouring and drinking of wine, merriment, bonfires, and most likely a form of gift giving. Not much more is known about the way it was celebrated.

On a larger scale, “there was a festival once every fifth year at Sunium in honor of Poseidon – evidently, then, a major event. Also, animal offerings to Poseidon were a common feature at the feast days of other gods, including the “festival at the temple of Hera on the 27th of Gamelion,” which honored the goddess “together with Zeus the Accomplisher, Kourotrophos and Poseidon.”

Related Festivals:

- Haloea – Jan 8 thru 9th

- Poseidonia of Aegina – A Midwinter Festival lasting as long as 2 months

Collected from various sources

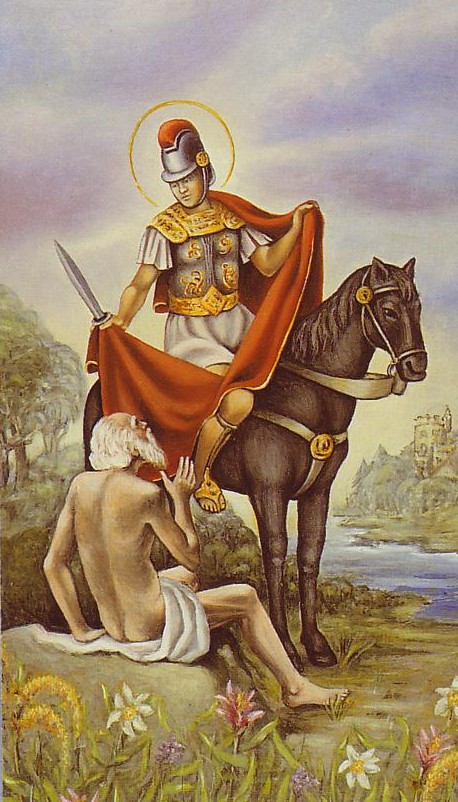

Saint Martin’s Day, also known as the Feast of Saint Martin, Martinstag or Martinmas, as well as Old Halloween and Old Hallowmas Eve, is the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours (Martin le Miséricordieux) and is celebrated on November 11 each year. This is the time when autumn wheat seeding was completed, and the annual slaughter of fattened cattle produced “Martinmas beef”. Historically, hiring fairs were held where farm laborers would seek new posts.

Saint Martin of Tours started out as a Roman soldier then was baptized as an adult and became a monk. It is understood that he was a kind man who led a quiet and simple life. The best known legend of his life is that he once cut his cloak in half to share with a beggar during a snowstorm, to save the beggar from dying from the cold. That night he dreamed that Jesus was wearing the half-cloak. Martin heard Jesus say to the angels, “Here is Martin, the Roman soldier who is now baptized; he has clothed me.”

St. Martin was known as friend of the children and patron of the poor. This holiday originated in France, then spread to the Low Countries, the British Isles, Germany, Scandinavia, and Eastern Europe. It celebrates the end of the agrarian year and the end of the harvest.

Bishop Perpetuus of Tours, who died in 490, ordered fasting three days a week from the day after Saint Martin’s Day (11 November). In the 6th century, local councils required fasting on all days except Saturdays and Sundays from Saint Martin’s Day to Epiphany (the Feast of the Three Wise Men and the star, c.f. Matthew 2: 1-12) on January 6, a period of 56 days, but of 40 days fasting, like the fast of Lent. It was therefore called Quadragesima Sancti Martini (Saint Martin’s Lent). This period of fasting was later shortened and called “Advent” by the Church.

The goose became a symbol of St. Martin of Tours because of a legend that when trying to avoid being ordained bishop he had hidden in a goose pen, where he was betrayed by the cackling of the geese. St. Martin’s feast day falls in November, when geese are ready for killing.

St. Martin’s Day was an important medieval autumn feast, and the custom of eating goose spread to Sweden from France. It was primarily observed by the craftsmen and noblemen of the towns. In the peasant community, not everyone could afford to eat goose, so many ate duck or hen instead.

Martinmas

Martinmas literally means “Mass of Martin”, or the day when Catholics celebrate the Holy Catholic Mass which honors St. Martin in a special way.

Martinmas, as a date on the calendar, has two meanings: in the agricultural calendar it marks the beginning of the natural winter, but in the economic calendar it is seen as the end of autumn. The feast coincides not only with the end of the Octave of All Saints, but with harvest-time, the time when newly produced wine is ready for drinking, and the end of winter preparations, including the butchering of animals.

An old English saying is “His Martinmas will come as it does to every hog,” meaning “he will get his comeuppance” or “everyone must die”. Because of this, St. Martin’s Feast is much like the American Thanksgiving – a celebration of the earth’s bounty. Because it also comes before the penitential season of Advent, it is seen as a mini “carnivale”, with all the feasting and bonfires.

As at Michaelmas on 29 September, goose is eaten in most places. Following these holidays, women traditionally moved their work indoors for the winter, while men would proceed to work in the forests.

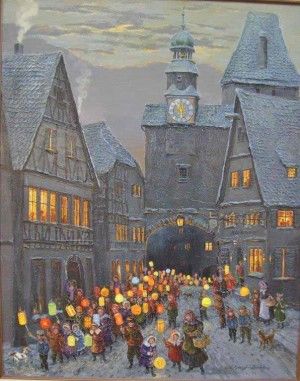

In some countries, Martinmas celebrations begin at the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of this eleventh day of the eleventh month (that is, at 11:11 am on November 11). In others, the festivities commence on St. Martin’s Eve (that is, on November 10). Bonfires are built and children carry lanterns in the streets after dark, singing songs for which they are rewarded with candy.

It is also a day of wine tasting and drinking.

Celebrations around the world:

- Austria

“Martinloben” is celebrated as a collective festival. Events include art exhibitions, wine tastings, and live music. “Martinigansl” (roasted goose) is the traditional dish of the season. In Austria St. Martin’s Day is celebrated the same way as in Germany.The nights before and on the night of Nov. 11, children walk in processions carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing Martin songs.

- Belgium

The day is celebrated on the evening of November 11 in a small part of Belgium (mainly in the east of Flanders and around Ypres). Children go through the streets with paper lanterns and candles, and sing songs about St. Martin. Sometimes, a man dressed as St. Martin rides on a horse in front of the procession.

In some areas, there is a traditional goose meal, although in West Flanders there is no specific meal; in other areas it is more a day for children, with toys brought on the night of 10 to 11 November. In the east part of the Belgian province of West Flanders, especially around Ypres, children receive presents from either their friends or family as supposedly coming from St. Martin on November 11. In other areas it is customary that children receive gifts later in the year from either their friends or family as supposedly coming from Saint Nicholas on December 5 or 6 (called Sinterklaas in Belgium and the Netherlands) or Santa Claus on December 25.

In other areas, children go from door to door, singing traditional “Sinntemette” songs, sporting a hollow beetroot with a carved face and a candle inside. Later in the evening there is a bonfire where all of them gather. At the end the beetroots are thrown into the fire, and pancakes are being served.

- Croatia, Slovenia

In Croatia, St. Martin’s Day (Martinje, Martinovanje) marks the day when the must traditionally turns to wine. The must is usually considered impure and sinful, until it is baptized and turned into wine. The baptism is performed by someone who dresses up as a bishop and blesses the wine; this is usually done by the host. Another person is chosen as the godfather of the wine. The foods traditionally eaten on the day are goose and home-made or store bought mlinci.

The biggest event in Slovenia is the St. Martin’s Day celebration in Maribor which marks the symbolic winding up of all the wine growers’ endeavours. There is the ceremonial “christening” of the new wine, and the arrival of the Wine Queen. The square Trg Leona Štuklja is filled with musicians and stalls offering autumn produce and delicacies.

- Slovakia

In Slovakia, the Feast of St. Martin is like a “2nd Birthday” for those named after this saint. Small presents or money are common gifts for this special occasion. Tradition says that if it snows on the feast of St. Martin, November 11, then St. Martin came on a white horse and there will be snow on Christmas day. However, if it doesn’t snow on this day, then St. Martin came on a dark horse and it will not snow on Christmas.

- Czech Republic

A Czech proverb connected with the Feast of St. Martin – Martin přijíždí na bílém koni (trans. “Martin is coming on a white horse”) – signifies that the first half of November in the Czech Republic is the time when it often starts to snow. St. Martin’s Day is the traditional feast day in the run-up to Advent.

Roasted goose is usually found on restaurant menus, and the Czech version of Beaujolais nouveau, Svatomartinské víno, a young wine from the recent harvest, which has recently become more widely available and popular. Wine shops and restaurants around Prague pour the first of the St. Martin’s wines at 11:11 a.m. Many restaurants offer special menus for the day, featuring the traditional roast goose.

- Denmark

In Denmark, Mortensaften, meaning the evening of St. Martin, is celebrated with traditional dinners, while the day itself is rarely recognized. (Morten is the Danish vernacular form of Martin.) The background is the same legend as mentioned above, but nowadays the goose is most often replaced with a duck due to size, taste and/or cost.

- Estonia

In Estonia, Martinmas signifies the merging of Western European customs with local Balto-Finnic pagan traditions. It also contains elements of earlier worship of the dead as well as a certain year-end celebration that predates Christianity. For centuries mardipäev (Martinmas) has been one of the most important and cherished days in the Estonian folk calendar. It remains popular today, especially among young people and the rural population. Martinmas celebrates the end of the agrarian year and the beginning of the winter period.

Among Estonians, Martinmas also marks the end of the period of All Souls, as well as the autumn period in the Estonian popular calendar when the souls of ancestors were worshiped, a period that lasted from November 1 to Martinmas (November 11). On this day children disguise themselves as men and go from door to door, singing songs and telling jokes to receive sweets.

In Southern Estonia, November is called Märtekuu after St. Martin’s Day.

- Germany

A widespread custom in Germany is bonfires on St. Martin’s eve, called “Martinsfeuer.” In recent years, the processions that accompany those fires have been spread over almost a fortnight before Martinmas. At one time, the Rhine River valley would be lined with fires on the eve of Martinmas. In the Rhineland region, Martin’s day is celebrated traditionally with a get-together during which a roasted suckling pig is shared with the neighbors.

The nights before and on the night of Nov. 11, children walk in processions carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing Martin songs. Usually, the walk starts at a church and goes to a public square. A man on horseback dressed like St. Martin accompanies the children. When they reach the square, Martin’s bonfire is lit and Martin’s pretzels are distributed.

In some regions of Germany (e.g. Rhineland or Bergisches Land) in a separate procession the children also go from house to house with their lanterns, sing songs and get candy in return.

The origin of the procession of lanterns is unclear. To some, it is a substitute for the St. Martin bonfire, which is still lit in a few cities and villages throughout Europe. It formerly symbolized the light that holiness brings to the darkness, just as St. Martin brought hope to the poor through his good deeds. Even though the tradition of the large, crackling fire is gradually being lost, the procession of lanterns is still practiced.

The tradition of the St. Martin’s goose or “Martinsgans”, which is typically served on the evening of St. Martin’s feast day following the procession of lanterns, most likely evolved from the well-known legend of St. Martin and the geese. “Martinsgans” is usually served in restaurants, roasted, with red cabbage and dumplings.

In some regions of Germany, the traditional sweet of Martinmas is “Martinshörnchen”, a pastry shaped in the form of a croissant, which recalls both the hooves of St. Martin’s horse and, by being the half of a pretzel, the parting of his mantle. In parts of western Germany these pastries are instead shaped like men (Stutenkerl or Weckmänner).

- Great Britain

In the United Kingdom, St. Martin’s Day is known as Martinmas (or sometimes Martlemass). It is one of the term days in Scotland. Many schools celebrate St. Martin’s day. Many schools are also named after St. Martin.

Martlemass beef was from cattle slaughtered at Martinmas and salted or otherwise preserved for the winter. The now largely archaic term “St. Martin’s Summer” referred to the fact that in Britain people often believed there was a brief warm spell common around the time of St. Martin’s Day, before the winter months began in earnest. A similar term that originated in America is “Indian Summer”.

- Ireland

In Ireland, on the eve of St. Martin’s Day, it is tradition to sacrifice a cockerel by bleeding it. The blood was collected and sprinkled on the four corners of the house. Also in Ireland, no wheel of any kind was to turn on St. Martin’s Day, because Martin was thrown into a mill stream and killed by the wheel and so it was not right to turn any kind of wheel on that day.

- Sicily

In Sicily, November is the winemaking season. On St. Martin’s Day Sicilians eat anise biscuits washed down with Moscato, Malvasia or Passito. More precisely, the hard biscuits are dipped into the Moscato. l’Estate di San Martino (Saint Martin’s Summer) is the traditional Sicilian reference to a period of unseasonably warm weather in early to mid November. Saint Martin’s Day is celebrated in a special way in a village near Messina and at a monastery dedicated to him overlooking Palermo beyond Monreale.

- Latvia

Mārtiņi (Martin’s) is traditionally celebrated by Latvians on November 10, marking the end of the preparations for winter, such as salting meat and fish, storing the harvest and making preserves. Mārtiņi also marks the beginning of masquerading and sledding, among other winter activities.

- Malta

St. Martin’s Day (Jum San Martin in Maltese) is celebrated in Malta on the Sunday nearest to November 11. Children are given a bag full of fruits and sweets associated with the feast, known by the Maltese as Il-Borża ta’ San Martin, “St. Martin’s bag”.

This bag may include walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, chestnuts, dried or processed figs, seasonal fruit (like oranges, tangerines, apples and pomegranates) and “Saint Martin’s bread roll” (Maltese: Ħobża ta’ San Martin). In old days, nuts were used by the children in their games.

There is a traditional rhyme associated with this custom:

Ġewż, Lewż, Qastan, Tin

Kemm inħobbu lil San Martin.

Walnuts, Almonds, Chestnuts, Figs

I love Saint Martin so much.

A feast is celebrated in the village of Baħrija on the outskirts of Rabat (Malta), including a procession led by the statue of Saint Martin. There is also a fair, and a show for local animals. San Anton School, a private school on the island, organises a walk to and from a cave especially associated with Martin in remembrance of the day.

- Netherlands

The day is celebrated on the evening of the 11th of November (the day Saint Martin died), where he is known as Sint-Maarten. As soon it gets dark, children up to the age of 11 or 12 (primary school age) go door to door with hand-crafted lanterns made of hollowed-out sugar beet or, more recently, paper, singing songs such as “Sinte Sinte Maarten,” hoping to receive candy in return, similar to Halloween.

In the past, poor people would visit farms on the 11th of November, to get food for the winter. In the 1600’s, the city of Amsterdam held boat races. 400 to 500 light craft, both rowing boats and sailboats, took part under the eyes of a vast crowd on the banks.

- Poland

St. Martin’s Day is celebrated mainly in the city of Poznań. On November 11, the people of Poznań buy and eat considerable amounts of “Rogale” (pronounced Ro-gah-leh), locally produced croissants, made specially for this occasion, filled with almond paste with poppy seeds, so-called “Rogal świętomarciński” or Martin Croissants or St. Martin Croissants.

Legend has it this centuries-old tradition commemorates a Poznań baker’s dream. His nighttime reveries had St. Martin entering the city on a white horse that lost its golden horseshoe. The very next morning, the baker whipped up horseshoe-shaped croissants filled with almonds, white poppy seeds and nuts, and gave them to the poor.

In recent years, competition amongst local bakeries has become fierce for producing the best “Rogale,” and very often bakeries proudly display a certificate of compliance with authentic, traditional recipes. Poznanians celebrate with a feast, specially organised by the city. There are different concerts, a St. Martin’s parade and a fireworks show.

- Portugal

In Portugal, St. Martin’s Day is commonly associated with the celebration of the maturation of the year’s wine, being traditionally the first day when the new wine can be tasted.

It is celebrated, traditionally around a bonfire, eating the magusto, chestnuts roasted under the embers of the bonfire (sometimes dry figs and walnuts), and drinking a local light alcoholic beverage called água-pé (literally “foot water”, made by adding water to the pomace left after the juice is pressed out of the grapes for wine – traditionally by stomping on them in vats with bare feet, and letting it ferment for several days), or the stronger jeropiga (a sweet liquor obtained in a very similar fashion, with aguardente added to the water). Água-pé, though no longer available for sale in supermarkets and similar outlets (it is officially banned for sale in Portugal), is still generally available in small local shops from domestic production.

Leite de Vasconcelos regarded the magusto as the vestige of an ancient sacrifice to honor the dead and stated that it was tradition in Barqueiros to prepare, at midnight, a table with chestnuts for the deceased family members to eat. The people also mask their faces with the dark wood ashes from the bonfire. A typical Portuguese saying related to Saint Martin’s Day:

É dia de São Martinho;

comem-se castanhas, prova-se o vinho.

It is St. Martin’s Day,

we’ll eat chestnuts, we’ll taste the wine.

This period is also quite popular because of the usual good weather period that occurs in Portugal in this time of year, called Verão de São Martinho (St. Martin’s Summer). It is frequently tied to the legend since Portuguese versions of St. Martin’s legend usually replace the snowstorm with rain (because snow is not frequent in most parts of Portugal, while rain is common at that time of the year) and have Jesus bringing the end of it, thus making the “summer” a gift from God.

- Spain

In Spain, St. Martin’s Day is the traditional day for slaughtering fattened pigs for the winter. This tradition has given way to the popular saying “A cada cerdo le llega su San Martín”, which translates as “Every pig gets its St Martin.” The phrase is used to indicate that wrongdoers eventually get their comeuppance.

- St. Maarten / St. Martin

In Sint Maarten, November 11 is St. Martin’s Day, not because of the same traditions as in other countries but that’s the date when the island was discovered by Christopher Columbus, in 1493. It is a public holiday on both sides to commemorate this event. Celebrations highlight tradition music, culture, and food.

- Sweden

St Martin’s Day was an important medieval autumn feast, and the custom of eating goose spread to Sweden from France. In early November, geese are ready for slaughter, and on St. Martin’s Eve, November 10, it is time for the traditional dinner of roast goose.

The custom is particularly popular in Skåne in southern Sweden, where goose farming has long been practiced, but it has gradually spread northwards. A proper goose dinner also includes apple charlotte.

- Switzerland

Its celebration has mainly remained a tradition in the Swiss Catholic region of the Ajoie in the canton of Jura. The traditional gargantuan feast, the Repas du Saint Martin, includes all the parts of freshly butchered pigs, accompanied by shots of Damassine, and lasting for at least 5 hours.

- United States

In the United States St. Martin’s Day celebrations are uncommon, and when they do happen, reflect the cultural heritage of a local community.

Many German restaurants feature a traditional menu with goose and gluhwein (a mulled red wine). St. Paul, Minnesota celebrates with a traditional lantern procession around Rice Park. The evening includes German treats and traditions that highlight the season of giving. In Dayton, Ohio the Dayton Liederkranz-Turner organization hosts a St. Martin’s Family Celebration on the weekend before with an evening lantern parade to the singing of St. Martin’s carols, followed by a bonfire.

- Other customs

The Auvergne region of central France traditionally hosts horse fairs on St. Martin’s Day.

Source: Wikipedia

Bonfire Night is a name given to various annual celebrations characterized by bonfires and fireworks. The event celebrates different traditions on different dates, depending on the country. Some of the most popular instances include the following:

- Walpurgis Night – Apr 30 – Scandinavia

- St John’s Eve – Jun 23 – Ireland, Spain, Northern Portugal

- Eleventh Night – Jul 11 – Northern Ireland

- Feast of the Assumption – Aug 15 – Northern Ireland

- Guy Fawkes Night – Nov 5 – in Great Britain, Newfoundland and Labrador

Note: This is by no means a complete list of celebrations referred to as “Bonfire Night.”

In Great Britain, Bonfire Night is associated with the tradition of celebrating the failure of Guy Fawkes’ actions on 5 November 1605. The British festival is, therefore, on 5 November, although some commercially driven events are held at a weekend near to the correct date, to maximize attendance.

Also known as:

- Bonfire Night

- Guy Fawkes Day

- Firework Night

Bonfire night’s sectarian significance has generally been lost: it is now usually just a night of revelry with a bonfire and fireworks, although an effigy of Guy Fawkes is burned on the fire. Celebrations are held throughout Great Britain; in some non-Catholic communities in Northern Ireland; and in some other parts of the Commonwealth. In the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, 5 November is commemorated with bonfires and firework displays, and it is officially celebrated in South Africa.

There are many food items that are associated with Bonfire Night. Toffee apples, treacle toffee, black peas and parkin, and even the jacket potato, are traditionally eaten around Bonfire Night in parts of England.

This Day in History

The history of this annual commemoration begins with the events of 5 November 1605, when Guy Fawkes, a member of the Gunpowder Plot, was arrested while guarding explosives the plotters had placed beneath the House of Lords. Celebrating the fact that King James I had survived the attempt on his life, people lit bonfires around London; and months later, the introduction of the Observance of 5th November Act enforced an annual public day of thanksgiving for the plot’s failure.

Within a few decades Gunpowder Treason Day, as it was known, became the predominant English state commemoration, but as it carried strong Protestant religious overtones it also became a focus for anti-Catholic sentiment. Puritans delivered sermons regarding the perceived dangers of popery, while during increasingly raucous celebrations common folk burnt effigies of popular hate-figures, such as the pope.

Towards the end of the 18th century reports appear of children begging for money with effigies of Guy Fawkes and 5 November gradually became known as Guy Fawkes Day. Towns such as Lewes and Guildford were in the 19th century scenes of increasingly violent class-based confrontations, fostering traditions those towns celebrate still, albeit peaceably.

In the 1850s changing attitudes resulted in the toning down of much of the day’s anti-Catholic rhetoric, and the Observance of 5th November Act was repealed in 1859. Eventually the violence was dealt with, and by the 20th century Guy Fawkes Day had become an enjoyable social commemoration, although lacking much of its original focus. The present-day Guy Fawkes Night is usually celebrated at large organised events, centered on a bonfire and extravagant firework displays.

Settlers exported Guy Fawkes Night to overseas colonies, including some in North America, where it was known as Pope Day. Those festivities died out with the onset of the American Revolution. Claims that Guy Fawkes Night was a Protestant replacement for older customs like Samhain are disputed, although another old celebration, Halloween, has lately increased in popularity, and according to some writers, may threaten the continued observance of 5 November.

One notable aspect of the Victorians’ commemoration of Guy Fawkes Night was its move away from the centers of communities, to their margins. Gathering wood for the bonfire increasingly became the province of working-class children, who solicited combustible materials, money, food and drink from wealthier neighbors, often with the aid of songs. Most opened with the familiar “Remember, remember, the fifth of November, Gunpowder Treason and Plot”.

The earliest recorded rhyme, from 1742, is reproduced below along with one bearing similarities to most Guy Fawkes Night ditties, recorded in 1903 at Charlton on Otmoor:

Don’t you Remember,

The Fifth of November,

‘Twas Gunpowder Treason Day,

I let off my gun,

And made’em all run.

And Stole all their Bonfire away.

~1742

The fifth of November, since I can remember,

Was Guy Faux, Poke him in the eye,

Shove him up the chimney-pot, and there let him die.

A stick and a stake, for King George’s sake,

If you don’t give me one, I’ll take two,

The better for me, and the worse for you,

Ricket-a-racket your hedges shall go.

~1903

Sources:

Bonfires of Saint John is a popular festival celebrated around June 24, (Saint John’s day) in several towns in Spain. For this festival, people gather together and create large bonfires from any kind of wood, such as old furniture, and share hot chocolate while teens and children jump over the fires.

A pie of tuna (coca anb tonyina) and early figs (bacores) is traditionally eaten while setting up the events.

The festival is celebrated throughout many cities and towns; however, the largest and most elaborate version is in Alicante. On the night of St John, gigantic (20 to 30 foot high) explosive caricatures (ninots) are paraded through the streets and exploded in a spectacular finale with fireworks and pyrotechnics, making this festival into the most important (and loudest!) cultural event in Alicantinian society.

Collected from various sources