Spring Festivals

The Romans had a celebration for just about everything. Certainly, any deity worth their salt got a holiday of their own, and Flora was no exception. She was the goddess of spring flowers and vegetation, and one of many fertility goddesses. In fact, she was so well respected as a fertility deity that she was often seen as a the patron deity of Roman prostitutes.

Her holiday originated around 235 b.c.e. It was believed that a good festival ensured that Flora would protect the blooming flowers around the city. However, at some point the celebration was discontinued — but it clearly took its toll when wind and hail did some serious damage to the flowers of Rome. In 173 b.c.e., the Senate reinstated the holiday, and renamed it the Ludi Floralis, which included public games and theatrical performances.

The Floralia took place during the five days between April 28 and May 3. Citizens celebrated with drinking and dancing. Flowers were everywhere, in the temples and on the heads of revelers. Anyone making an offering to Flora might give her a libration of milk and honey.

source: PaganWiccan

Mothering Sunday has been celebrated on the fourth Sunday of Lent since the 16th century. In Bristol, Mothering Sunday was commemorated with Mothering Buns as well as cakes.

A Mothering Bun is a circular, slightly enriched, bread bun with white sugar icing strewn with hundreds-and-thousands. These small, fairly plain yeast rolls were also topped with the much-appreciated caraway or aniseed comfits (candies) that also flavored bath buns and seed cake.

From The Verse-Book of a Homely Woman:

Then down to Farmer Westacott’s, there’s doings fine and grand,

Because young Jake is coming home from sea, you understand.

Put into port but yesternight, and when he steps ashore,

‘Tis coming home the laddie is, to Somerset once more.

And so her’s baking spicy cakes, and stirring raisins in,

To welcome of her only chick, who’s coming Mothering.

Here’s a recipe:

A specialty of Bristol, these are made by local bakers the day before Mothering Sunday. Traditionally, on this day only, the Lent fast was relaxed. The buns used to be decorated with caraway or aniseed; today, hundreds and thousands are used.

Ingredients for the buns:

- 500g strong white bread flour

- 1 tsp salt

- 50g caster sugar

- 7g sachet instant yeast

- 50g unsalted butter, diced and softened

- 300ml water

Ingredients for the icing:

- 200g icing sugar

- 2–3 tbsp water

Instructions:

Put the flour in a large bowl. Add the salt and sugar on one side, the yeast on the other. Add the butter and three-quarters of the water, then turn the mixture round with the fingers of one hand. Add the remaining water a little at a time, mixing until you have taken in all the flour and the dough is soft and slightly sticky; you might not need all the water.

Oil the work surface to stop the dough sticking. Turn out the dough and knead for 5 mins, or until smooth and no longer sticky. Lightly oil the bowl, return the dough to it and cover with cling film. Leave to rise for at least an hour, until doubled in size. Line 2 baking trays

with baking parchment.

Scrape the dough out of the bowl onto a lightly floured surface and fold it inwards repeatedly until all the air has been knocked out and the dough is smooth. Divide into 12 pieces.

Roll each piece into a ball by placing it into a cage formed by your hand on the work surface and moving your hand in a circular motion, rotating the ball rapidly.

Put the balls of dough on the prepared baking trays, spacing them slightly apart. (They should just touch each other when they have risen.) Place each tray in a clean plastic bag and leave to prove for about 40 mins, until the rolls have doubled in size. Heat the oven to 220C/Fan 200/425F.

Bake for 10–12 mins, until the rolls are golden and sound hollow when tapped underneath. Transfer to a wire rack to cool.

For the icing, mix the icing sugar with enough water to give a thick but pour-able consistency. Dip each roll into the icing and then into the hundreds and thousands. Makes 12 buns.

Sources: Foods of England and Simple Things

Mothering Sunday is a holiday celebrated by Catholic and Protestant Christians in some parts of Europe. It falls on the fourth Sunday in Lent, exactly three weeks before Easter.

The other names attributed to the fourth Sunday in Lent include:

- Refreshment Sunday

- Pudding Pie Sunday (in Surrey, England)

- Mid-Lent Sunday

- Simnel Sunday

- Rose Sunday

Simnel Sunday is named after the practice of baking simnel cakes to celebrate the reuniting of families during the austerity of Lent. (Here is a recipe: Simnel Cake.) Because there is traditionally a relaxation of Lenten vows on this particular Sunday in celebration of the fellowship of family and church, the name Refreshment Sunday is sometimes used, although rarely today.

Simnel cake is a traditional confection associated with both Mothering Sunday and Easter. Around 1600, when the celebration was only held in England and Scotland, a different kind of pastry was preferred. In England, “Mothering Buns” or “Mothering Sunday Buns” were made to celebrate. These sweet buns are topped with pink or white icing and the multi-colored sprinkles known as “hundreds and thousands” in the UK. (Here’s a recipe: Mothering Buns). They are not widely made or served today in the UK but in Australia they are a bakery staple, not related to any particular celebration. In Northern England and Scotland some preferred “Carlings”, pancakes made of steeped peas fried in butter.

It is sometimes said that Mothering Sunday was once observed as a day on which people would visit their “mother” church. During the 16th century, people returned to their mother church, the main church or cathedral of the area, for a service to be held on Laetare Sunday. This was either the church where they were baptized, or the local parish church, or more often the nearest cathedral.

Anyone who did this was commonly said to have gone “a-mothering”, although whether this term preceded the observance of Mothering Sunday is unclear. In later times, Mothering Sunday became a day when domestic servants were given a day off to visit their mother church, usually with their own mothers and other family members. The children would pick wild flowers along the way to place in the church or give to their mothers. Eventually, the religious tradition evolved into the Mothering Sunday secular tradition of giving gifts to mothers.

It was often the only time that whole families could gather together, since on other days they were prevented by conflicting working hours, and servants were not given free days on other occasions.

Whatever its origins, it is now an occasion for honoring the mothers of children and giving them presents. It is increasingly being called Mothers’ Day, although that has always been a secular event quite different from the original Mothering Sunday. In the UK and Ireland, Mothering Sunday is celebrated in the same way as Mothers’ Day is celebrated elsewhere.

By the 1920’s the custom of keeping Mothering Sunday had tended to lapse in Ireland and in continental Europe. In 1914, inspired by Anna Jarvis’s efforts in the United States, Constance Penswick-Smith created the Mothering Sunday Movement, and in 1921 she wrote a book asking for the revival of the festival.

Its wide scale revival was through the influence of American and Canadian soldiers serving abroad during World War II; the traditions of Mothering Sunday, still practiced by the Church of England and Church of Ireland were merged with the newly imported traditions and celebrated in the wider Catholic and secular society. UK-based merchants saw the commercial opportunity in the holiday and relentlessly promoted it in the UK; by the 1950’s, it was celebrated across all the UK.

People from Ireland and the UK started celebrating Mothers’ Day on the same day that Mothering Sunday was celebrated, the fourth Sunday in Lent. The two celebrations have now been mixed up, and many people think that they are the same thing.

Mothering Sunday remains in the calendar of some Canadian Anglican churches, particularly those with strong English connections.

Found at: Wikipedia

Also known as: Oestre, Easter, the Spring Equinox, Vernal (Spring) Equinox, Alban Eiler (Caledonii), Méan Earraigh

- March 20 – 23 Northern Hemisphere

- September 20 – 23 Southern Hemisphere

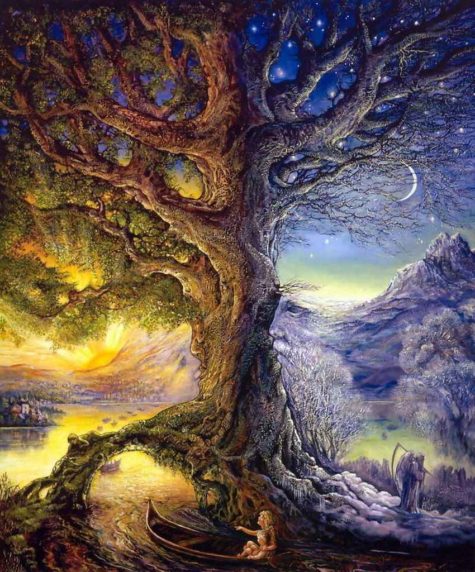

This is the official return of the young Goddess after her Winter hibernation. As with the other Equinox and the Solstices, the date of this festival may move slightly from year to year, but many will choose to celebrate it on 21 March.

The Spring Equinox is the point of equilibrium – when light and darkness are in balance but the light is growing stronger. The balance is suspended just before spring bursts forth from winter. Night and day are of equal length at the equinox, the forces of male and female are also in balance. Ostara is a festival of balance and fertility.

In keeping with the balance of the Equinox, Oestara is a time when we seek balance within ourselves. It is a time for throwing out the old and taking on the new. We rid ourselves of those things which are no longer necessary – old habits, thoughts and feelings – and take on new ideas and thoughts. This does not mean that you use this festival as a time for berating yourself about your ‘bad’ points, but rather that you should seek to find a balance through which you can accept yourself for what you are.

It is also a celebration of birth and new life. A day when death has no power over the living.

Spring has arrived, and with it comes hope and warmth. Deep within the cold earth, seeds are beginning to sprout. In the damp fields, the livestock are preparing to give birth. In the forest, under a canopy of newly sprouted leaves, the animals of the wild ready their dens for the arrival of their young. Spring is here.

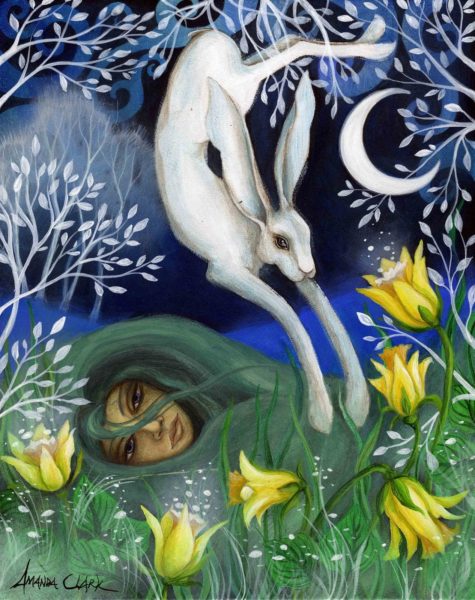

It is no coincidence that the name for this sabbat sounds similar to the word ‘Easter’. Eostre, or Ostara, is an Anglo-Saxon Dawn Goddess whose symbols are the egg and the hare. She, in turn, is the European version of the Goddess Ishtar or Astarte, whose worship dates back thousands of years and is certainly pre-Christian. Eostre also lives on in our medical language in the words ‘oestrous’ (the sexual impulse in female animals) and ‘oestrogen’ (a female hormone).

Today, Oestara is celebrated as a spring festival. Although the Goddess put on the robes of Maiden at Imbolg, here she is seen as truly embodying the spirit of spring. By this time we can see all around us the awakened land, the leaves on the trees, the flowers and the first shoots of corn.

There is some debate as to whether Oestara or Imbolg was the traditional time of spring cleaning, but certainly the casting out of the old would seem to be in sympathy with the spirit of this festival and the increased daylight at this time encourages a good clean out around the home.

The Easter Bunny also is of Pagan origin, as are baskets of flowers. Brightly colored eggs represent the child within.

Traditionally, Ostara is a time for collecting wildflowers, walking in nature’s beauty and cultivating herb gardens. Half fill a bowl with water and place a selection of flowers into it for display in a prominent position in your home.

This is the time to free yourself from anything in the past that is holding you back.

Sources: varied

And frosts are slain and flowers begotten,

And in green underworld and cover

blossom by blossom the spring begins.

~Algernon Charles Swinburne

Méan Earraigh marks the spring equinox, when night and day are of equal length and spring officially begins. Birds begin their nesting and egg-laying, and eggs–symbolic of rebirth, fertility, and immortality–are tossed into fresh furrows or eaten by ploughmen. They are also carried by those engaged in spring planting.

A charming custom is painting eggs with symbols and pictures of what one wishes to manifest in the coming year. The eggs can then be buried in the Earth Mother, who hears the cries and dreams of her children. In some communities, eggs are hidden in the stores of seed grain and left there all season to bless the sowing and encourage the seeds to sprout. Dressed as mummers, “pace-eggers” go from house to house and demand eggs and coins in return for a short performance. Men and women exchange clothing for the show.

The eggs given to the pace-eggers have been wrapped in leaves, roots, flowers, and bark before boiling, to impart color. Later the eggs are used in games, such as attempting to strike an opponent’s legs. The eggs might be hidden or rolled down hillsides, after which they are eaten. Blood, ashes from sacred fires, fistfuls of salt, or handfuls of soil from a high mountaintop are scattered on the newly sown fields.

Offerings of food and milk are left for the faeries and other spirits who live in and around rocks and are responsible for the fertility of the land. A few fruits from the previous year’s harvest are left for the nature spirits. Sacred hilltops are visited, and picnics of figs, fig cakes, cider and ale are enjoyed. The figs are symbolic of fertility, the leaf being the male element and the fruit the female.

You can also celebrate the arrival of spring with flowers. Bring them into your own home and give them to others. You do not have to spend a lot of money – one or two blooms given for no other reason than ‘spring is here’ can often bring a smile to even the most gloomy face.

A traditional Vernal Equinox pastime is to go to a field and randomly collect wildflowers (thank the flowers for their sacrifice before picking them). Or, buy some from a florist, taking one or two of those that appeal to you. Then bring them home and divine their Magickal meanings by the use of books, your own intuition, a pendulum, this post on the Magickal Meanings of Flowers, or by other means. The flowers you’ve chosen reveal your inner thoughts and emotions.

In the druidic tradition, Aengus Og is the male deity of the occasion. Son of In Dagda and Boand, he was conceived and born while Elcmar, Boand’s husband, was under enchantment. When three days old, Aengus was removed to be fostered by Midir, god of the Otherworld mound at Bri Leith, with his three hostile cranes. These birds guarded the mound and prevented the approach of travelers, and were said to cause even warriors to turn and flee.

Make an Altar to Ostara.

Ostara, the ancient German Virgin Goddess of Spring, loves bright colors. The light pastels of spring are perfect offerings for Ostara. To represent earth on your altar, choose bright or pastel colored stones like Rose Quartz, Amethyst, or any of the Calcites (blue, red, yellow, or green). If you have some Citrine, be sure to include it. Citrine has long been an aid for mental clarity.

Ostara, the ancient German Virgin Goddess of Spring, loves bright colors. The light pastels of spring are perfect offerings for Ostara. To represent earth on your altar, choose bright or pastel colored stones like Rose Quartz, Amethyst, or any of the Calcites (blue, red, yellow, or green). If you have some Citrine, be sure to include it. Citrine has long been an aid for mental clarity.

By including an offering of colored eggs on your altar, you will be taking part in an ancient tradition (still performed!) by the Germanic people. Ostara has been honored this time of year with painted eggs for centuries.

To symbolize fertility, in addition to the eggs, you can include seeds or rice on your altar. I like to use rice as a symbol for fertility on my altars.

Incense and feathers are perfect symbols for air on your altar. It is important for Ostara’s altar that you include a symbol for air because Ostara herself is the living symbol for Air. (This must be the way Ostara and Easter became associated with birds, i.e. chickens) Be sure to burn incense at your altar when you are dedicating it to bring in the energy and vibrational qualities of Ostara.

The perfect time to dedicate your altar is at dawn. Choose a day, then plan to dedicate your altar to Ostara at dawn’s first light by lighting incense and repeating an invocation to her as well as a prayer of thanksgiving for all that Ostara symbolizes in your life:

- A clear mind.

- New beginnings.

- Personal renewal.

- Fertility, either for the purpose of bearing a child or for creativity such as arts and crafts, writing, or decorating.

You can include anything you like on your altar to Ostara. You will know by how you feel if an item is appropriate or not. I believe it is important to include symbols for the four elements on my altars. The four elements are Fire, Earth, Air, and Water. The four Calcites on my altar (red/fire, green/earth, yellow/air, and blue/water) represent Mother Earth and the four elements. I have added feathers and other items that symbolize Ostara to my altar as offerings to her.

Last, but not least, it might be nice to include a figure of a rabbit. The rabbit is Ostara’s power animal. I am sure this is because of their propensity for fertility.

Sources:

March 17 commemorates Saint Patrick, the patron saint and national apostle of Ireland, and the arrival of Christianity in Ireland. In addition, this day also celebrates the heritage and culture of the Irish in general.

Celebrations generally involve public parades and festivals, céilithe (Irish traditional music sessions), and the wearing of green attire or shamrocks. There are also formal gatherings such as banquets and dances, although these were more common in the past. St Patrick’s Day parades began in North America in the 18th century but did not spread to Ireland until the 20th century.

The participants generally include marching bands, the military, fire brigades, cultural organisations, charitable organisations, voluntary associations, youth groups, fraternities, and so on. However, over time, many of the parades have become more akin to a carnival. More effort is made to use the Irish language; especially in Ireland, where the week of St Patrick’s Day is “Irish language week”. Recently, famous landmarks have been lit up in green on St Patrick’s Day.

Christians also attend church services and the Lenten restrictions on eating and drinking alcohol are lifted for the day. Perhaps because of this, drinking alcohol – particularly Irish whiskey, beer or cider – has become an integral part of the celebrations.

The St Patrick’s Day custom of ‘drowning the shamrock‘ or ‘wetting the shamrock‘ was historically popular, especially in Ireland. At the end of the celebrations, shamrock is put into the bottom of a cup, which is then filled with whiskey, beer or cider. It is then drank as a toast; to St Patrick, to Ireland, or to those present. The shamrock would either be swallowed with the drink, or be taken out and tossed over the shoulder for good luck.

In every household the herb is placed upon the breakfast table of the master and the mistress, who “drown the shamrock” in generous draughts of whiskey, and then send the bottle down into the kitchen for the servants.

On St Patrick’s Day it is customary to wear shamrocks and/or green clothing or accessories (the “wearing of the green”). St Patrick is said to have used the shamrock, a three-leaved plant, to explain the Holy Trinity to the pagan Irish. This story first appears in writing in 1726, though it may be older.

On St Patrick’s Day it is customary to wear shamrocks and/or green clothing or accessories (the “wearing of the green”). St Patrick is said to have used the shamrock, a three-leaved plant, to explain the Holy Trinity to the pagan Irish. This story first appears in writing in 1726, though it may be older.

Long before the shamrock became associated with St. Patrick’s Day, the four-leaf clover was regarded by ancient Celts as a charm against evil spirits.

In pagan Ireland, three was a significant number and the Irish had many triple deities, a fact that may have aided St Patrick in his evangelisation efforts. Patricia Monaghan says there is no evidence that the shamrock was sacred to the pagan Irish. However, Jack Santino speculates that it may have represented the regenerative powers of nature, and was recast in a Christian context—icons of St Patrick often depict the saint “with a cross in one hand and a sprig of shamrocks in the other”. Roger Homan writes, “We can perhaps see St Patrick drawing upon the visual concept of the triskele when he uses the shamrock to explain the Trinity”.

In the early 1900’s, O. H. Benson, an Iowa school superintendent, came up with the idea of using a clover as the emblem for a newly founded agricultural club for children in his area. In 1911, the four-leaf clover was chosen as the emblem for the national club program, later named 4-H.

The color green has been associated with Ireland since at least the 1640’s, when the green harp flag was used by the Irish Catholic Confederation. Green ribbons and shamrocks have been worn on St Patrick’s Day since at least the 1680s. The Friendly Brothers of St Patrick, an Irish fraternity founded in about 1750, adopted green as its color.

However, when the Order of St. Patrick—an Anglo-Irish chivalric order—was founded in 1783 it adopted blue as its color, which led to blue being associated with St Patrick. During the 1790’s, green would become associated with Irish nationalism, due to its use by the United Irishmen. This was a republican organisation—led mostly by Protestants but with many Catholic members—who launched a rebellion in 1798 against British rule.

The phrase “wearing of the green” comes from a song of the same name, which laments United Irishmen supporters being persecuted for wearing green. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the color green and its association with St Patrick’s Day grew.

The wearing of the ‘St Patrick’s Day Cross’ was also a popular custom in Ireland until the early 20th century. These were a Celtic Christian cross made of paper that was “covered with silk or ribbon of different colors, and a bunch or rosette of green silk in the center”.

The most popular of the many legends about St. Patrick is the one which credits him for having driven all the snakes and vermin out of Ireland.

Here’s an old old poem about it:

There’s not a mile in Ireland’s isle

where the dirty vermin musters;

Where’er he put his dear forefoot

he murdered them in clusters.

The toads went hop, the frogs went flop,

slap dash into the water,

And the beasts committed suicide to

save themselves from slaughter.

Nine hundred thousand vipers blue

he charmed with sweet discourses.

And dined on them at Killaloo

in soups and second courses.

When blindworms crawling on the grass

disgusted all the nation,

He gave them a rise and opened their eyes

to a sense of the situation.

The Wicklow Hills are very high, and

so’s the Hill of Howth, sir;

But there’s a hill much higher still—ay,

higher than them both, sir;

‘Twas on the top of this high hill St.

Patrick preached the sarmint

That drove the frogs into the bogs and

bothered all the varmint.

About St Patrick

Patrick was a 5th-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Much of what is known about Saint Patrick comes from the Declaration, which was allegedly written by Patrick himself. It is believed that he was born in Roman Britain in the fourth century, into a wealthy Romano-British family. His father was a deacon and his grandfather was a priest in the Christian church.

Patrick was a 5th-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Much of what is known about Saint Patrick comes from the Declaration, which was allegedly written by Patrick himself. It is believed that he was born in Roman Britain in the fourth century, into a wealthy Romano-British family. His father was a deacon and his grandfather was a priest in the Christian church.

According to the Declaration, at the age of sixteen, he was kidnapped by Irish raiders and taken as a slave to Gaelic Ireland. ] It says that he spent six years there working as a shepherd and that during this time he “found God”. The Declaration says that God told Patrick to flee to the coast, where a ship would be waiting to take him home. After making his way home, Patrick went on to become a priest.

According to tradition, Patrick returned to Ireland to convert the pagan Irish to Christianity. The Declaration says that he spent many years evangelising in the northern half of Ireland and converted “thousands”. Patrick’s efforts against the druids were eventually turned into an allegory in which he drove “snakes” out of Ireland (Ireland never had any snakes).

Tradition holds that he died on 17 March and was buried at Downpatrick. Over the following centuries, many legends grew up around Patrick and he became Ireland’s foremost saint.

NOTE:

What many people don’t realize is that the serpent was actually a metaphor for the early Pagan faiths of Ireland. St. Patrick brought Christianity to the Emerald Isle, and did such a good job of it that he practically eliminated Paganism from the country. Because of this, some modern Pagans refuse to observe a day which honors the elimination of the old religion in favor of a new one. It’s not uncommon to see Pagans and Wiccans wearing some sort of snake symbol on St. Patrick’s Day, instead of those green “Kiss Me I’m Irish” badges.

Sources: Almanac.com, Wikipedia, and Encyclopaedia of Superstitions, Folklore, and the Occult Sciences

- Other names: Damballah Weddo, Da, Papa Damballa, Obatala

- Holiday: March 17 (St. Patrick’s Day)

Associated Catholic Saint Patrick (who drove the snakes out of Ireland), and sometimes also Moses, whose staff transformed into a snake to prove the power of God over that wielded by Egyptian priests, Damballah is the primordial snake Iwa of life, wealth and wisdom. He is venerated in Dahomey as well as Haitian Vodou. He may also survive in the New Orleans folk saint Blanc Dani.

He is one of the most important of all the loa, Damballa is the Sky Father and the primordial creator of all life. He rules the mind, intellect, and cosmic equilibrium. Damballa, as the serpent spirit and “The Great Master”, created the cosmos by using his 7,000 coils to form the stars and the planets in the heavens and to shape the hills and valleys on earth. By shedding the serpent skin, Damballa created all the waters on the earth.

Read more about him here: Damballah

Offerings:

For a very traditional offering, make a bed or hill of white flour on a perfectly clean, pure white plate. Nestle one whole, raw white egg into the center of the flour and serve.

Other offerings could include white candles and white foods like rice, milk, whole raw eggs (leave them plain or rub gently with rose or other mildly scented, fine quality floral water), corn syrup, white chickens, or white flowers. More lavish offerings might include luxurious white fabrics, crystal or porcelain eggs and/or snakes.

He is a stickler for cleanliness. He doesn’t like strong, pervasive odors of any kind, but especially tobacco. If you smoke, then do so far from his altar space or anywhere associated with him. He may object to cleaning products with strong odors too, as well as air fresheners with strong aromas. Rooms should smell clean and fresh. Open a window to aerate them. He does not object to light floral odors, like rose or orange blossom water, and traditionally expresses a fondness for Pompeii Lotion, a cologne product found in botanicas and spiritual supply stores.

From: Encyclopedia of Spirits

March 12th, is the Feast of Marduk, an ancient Babylonian God. Acknowledged as the creator of the universe and of humankind, the god of light and life, and the ruler of destinies, he rose to such eminence that he claimed 50 titles.

The epic poem Enûma Elish tells the story of Marduk’s birth, heroic deeds and becoming the ruler of the gods. Also included in this document are The Fifty Names of Marduk. You can read more about Marduk at The Powers That Be.

Aside from being a fertility god and god of thunderstorms, Marduk’s original character is obscure. Later he became connected with water, vegetation, judgment, and magic. He is normally referred to as Bel “Lord”, also bel rabim “great lord”, bêl bêlim “lord of lords”, ab-kal ilâni bêl terêti “leader of the gods”, aklu bêl terieti “the wise, lord of oracles”, muballit mîte “reviver of the dead”, etc.

A Ritual for Marduk’s Feast Day:

- Colors: Light blue and grey

- Element: Air

- Altar: On a cloth of pale blue place a naked sword, three grey candles, and a loaf of bread shaped like a dragon.

- Offerings: Cut something into pieces.

- Daily meal: Fish or meat, chopped finely.

Invocation to Marduk

The warrior’s sword is clean and bright

And has two edges. So Marduk found.

Taking up the sword, he slew

The Dragon Mother Tiamat

And from her body carved the earth

And the overarching sky.

Yet he found, as we all do,

That he could not live anywhere

On this the new earth without

Remembering her, and all that she was,

And he lived and died surrounded

By her at the last,

And her body took his

When at last he was betrayed.

Beware, ye who would be king

By force of arms! Your enemies define you,

So choose them well.

(One who has been chosen to do the work of the ritual takes up the sword and cleaves the bread dragon into pieces, which are then passed around and eaten. Exit to the beating of a drum.)

From: Pagan Book of Hours

Traditionally the feast lasted for twelve days:

Five thousand years ago, in the cradle of Western civilization that lay between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates that we now call Iraq, the ancient Babylonians and Sumerians held their New Year celebrations at about the time of the Spring Equinox. These Mesopotamians (a word that means ‘[dwellers of the land between the rivers’), the Babylonians to the north and the Sumerians further to the south called this festival, respectively, Akitaand Zagmuk (or Zakmuk).

On the first three days, the priests would come to the high Temple of Marduk in Babylon, the Ésagila, and offer prayers of lamentation and supplication. These prayers were repeated on the fourth day, when the Enûma Eliš, the great Babylonian Epic of Creation, was recited, telling the story of Marduk’s victory over Tiamat.

On the fifth day, the king of Babylon came to the Ésagila, was stripped of his crown, robes and regalia, and was humiliated by the High Priest, who struck him in the face, symbolizing submission before the greater power of the god, after which his crown was returned, symbolizing the god’s approval of his royal and civic roles.

Marduk is then captured by the evil gods and held prisoner by them, in the Etemenanki, a seven-storey ziggurat (identified in the Torah and the Bible as the Tower of Babel), where he awaits the arrival of his son, Nabu. He arrives on day six, symbolized by a great, formal procession of the King and the citizens of Babylon to the Ésagila, and on day seven, Nabu frees his embattled father.

The eighth day saw the gathering of the statues of the gods in the hall of Destinies, where they bestow their powers on Marduk, confirming his primacy over them all. A victory procession to the House of Akita, situated outside the city walls, took place on the ninth day, as the populace celebrated Marduk’s defeat of Tiamat, and on the tenth day, Marduk returns to earth during the night and marries the goddess Ishtar, their roles acted by the King of Babylon and the High Priestess of the Ésagila.

The eleventh day sees the return to the hall of Destinies, where the gods and Marduk renew their covenant with mankind before they return to Heaven, and on the final day, the statues of the gods were returned to their places in the Ésagila and the king would be slain, so that his spirit could assist Marduk – although, in reality, a criminal would be elected as a proxy king and killed in place of the true king.

Note:

We can see here clear parallels here with the Lord of Misrule, a substitute king who takes over the responsibilities of the real king at the festival time, as well as story of Jesus and Barabbas in the New Testament, (Barabbas means, literally, ‘Son of the Lord’), and the wide-spread legends of the dying god who returns to life.

The twelve days of Zagmuk are the origins of our twelve days of Christmas, although moved from the Babylonian New Year to our New Year, and they may well be the intercalary adjustment of 11.25 days needed to reconcile the 354 days of the lunar year with the 365.25 days of the solar year.

The names and the mythology of Marduk were also incorporated into the fictional mythology of the Necronomicon. Each of the fifty names was given a power and a seal. These can be found here: About The Fifty Names of Marduk

Source: Wikipedia and The Study

A wonderful spiced and fruited cake which heralds the advent of Spring, simnel cake has a fascinating cultural heritage with roots that stretch back to the Romans and Athenians. In Britain, known as the Shrewsbury Simnel, it is simply made using white flour, fragrant spices and is generously studded with dried fruits and pungent peel.

Like a Christmas cake, it is covered with pale sweet almond paste. The decoration is plain – twelve little balls of smooth paste. A specially baked simnel cake is a wonderful gift to take to your mother for Matronalia, Mother’s Day, or Mothering Sunday Tea Time. Decorate it with crystalised flowers and tie some yellow ribbon around the side.

Ingredients:

For the almond paste:

- 400 g icing sugar, sifted

- 250 g ground almonds

- 1 large egg yolk, beaten lightly

- 3-4 tablespoons orange juice

- 5 drops almond essence

For the cake :

- 250 g plain flour

- 1 pinch salt

- 1 teaspoon nutmeg

- 1 teaspoon cinnamon

- 280 g currants

- 250 g sultanas

- 110 g mixed peel

- 160 g butter

- 160 g caster sugar

- 3 large eggs

- 200 ml milk, to mix

You will also need:

- a sifter,

- nest of bowls,

- food processor or electric beater,

- spatula,

- wooden spoon,

- 24 cm round cake tin,

- baking paper,

- brown paper and twine,

- rolling pin,

- thin metal skewer.

To make your own almond paste you will need:

- a food processor fitted with a steel blade.

- Don’t be tempted to use store-bought almond paste because it contains lots of sugar and few almonds, it will turn to liquid under the grill.

Directions:

Place icing sugar and almonds in food processor bowl. Process, slowly dripping in egg yolk, orange juice and almond essence. The mixture should form a pliable paste. Set aside a small portion for balls with which to decorate the cake. Roll out the remaining paste into 2 circles which are the approximate size of the tin. Set aside.

Preheat oven to 160°C/320°F.

Use a sturdy non-stick cake tub or line the buttered base with baking paper. As the baking period is long (1-1 1/2 hours), prevent the cake drying out by wrapping a double thickness of brown paper around the pan and securing it with twine.

Sift flour, salt and spices together, then stir in fruit and peel. Cream butter and sugar thoroughly until light and creamy then beat in eggs one at a time, until the mixture is fluffy. (Reserve a drop of egg yolk for brushing over top layer of almond paste.). Stir flour and fruit into creamed mixture (you may need to add a little milk to give the mixture a dropping consistency).

Place half the mixture into a greased and lined cake tin. Place one pre-rolled round of almond paste over the top. Cover with remaining cake mixture. Before baking the cake, give the pan of mixture a sharp tap on to a firm surface. This settles the mixture and prevents holes from forming in the cake.

Bake in the center of the oven for 1-1 1/4 hours or until a thin metal skewer inserted in the center of the cake comes out without a trace of stickiness. Level the cake by placing a weighted plate on top of the cooked cake while it is still hot.

Turn out cake on to a wire rack after leaving it to settle in the cake tin for between 10 and 15 minutes. Peel off paper and leave to cool completely.

Cover the top of the cake with a second round of almond paste. Roll 12 small balls of paste and place evenly around the top of the cake. Brush the top with a little beaten egg and very lightly brown under the grill until the almond paste turns light golden brown. Remove and leave to cool.

Note from someone who tried this recipe:

I did give the pan it’s tap to get rid of air bubbles but almost had a disaster when I went to take everything off so that I could set this on a cake rack to cool.. the almond paste in the middle was still liquid and was leaking down the sides of the cake at a great rate, so I quickly shoved it as neatly as I could back into the springform and let it cool completely before loosening it again. At least my baking paper helped stem the flow before I lost it all. Some of my twelve little balls slipped off while I had this in the oven the second time… so I’d advise not to put them too near to the edge of the cake.

According to archeological evidence from 2nd century A.D. Maslenitsa may be the oldest surviving Slavic holiday. Maslenitsa has its origins in the pagan tradition. In Slavic mythology, Maslenitsa is a sun-festival, personified by the ancient god Volos, and a celebration of the imminent end of the winter. In the Christian tradition, Maslenitsa is the last week before the onset of Great Lent.

During the week of Maslenitsa, meat is already forbidden to Orthodox Christians, and it is the last week during which eggs, milk, cheese and other dairy products are permitted, leading to its name of “Cheese-fare week” or “Crepe week”. The most characteristic food of Maslenitsa is bliny thin pancakes or crepes, made from the rich foods still allowed by the Orthodox tradition that week: butter, eggs and milk. Here’s a recipe: Classic Krasnye Blini

Since Lent excludes parties, secular music, dancing and other distractions from spiritual life, Maslenitsa represents the last chance to take part in social activities that are not appropriate during the more prayerful, sober and introspective Lenten season.

In some regions, each day of Maslenitsa had its traditional activity:

Monday:

Monday may be the welcoming of “Lady Maslenitsa”. The community builds the Maslenitsa effigy out of straw (из соломы), decorated with pieces of rags, and fixed to a pole formerly known as Kostroma. It is paraded around and the first pancakes may be made and offered to the poor.

Tuesday:

On Tuesday, young men might search for a fiancée to marry after lent.

Wednesday:

On Wednesday sons-in-law may visit their mother-in-law who has prepared pancakes and invited other guests for a party.

Thursday:

Thursday may be devoted to outdoor activities. People may take off work and spend the day sledding, ice skating, snowball fights and with sleigh rides.

Friday:

On Friday sons-in-law may invite their mothers-in-law for dinner.

Saturday: Saturday may be a gathering of a young wife with her sisters-in-law to work on a good relationship.

Sunday:

Relatives and friends ask each other for forgiveness and might offer them small presents. As the culmination of the celebration people gather to “strip Lady Maslenitsa of her finery” and burn her in a bonfire. Left-over pancakes may also be thrown into the fire and Lady Maslenitsa’s ashes are buried in the snow to “fertilize the crops”.

Found at: Wikipedia