What follows is a list (in alphabetical order) of the names given to the January moon. Also listed is the tradition and/or origin of that moon name:

- Avunniviayuk ~Inuit

- Big Cold Moon ~Mohawk

- Chaste Moon ~other

- Cold Meal Moon ~Natchez

- Cold Moon ~Cheokee

- Cooking Moon ~Choctaw

- Dark Moon ~Janic

- Disting Moon ~other

- Flying Ant Moon ~Apache

- Great Spirit Moon ~Anishnaabe

- Her Cold Moon ~Wishram

- Ice Moon ~San Juan, Neo-Pagan

- Icicle Moon ~Medicine Wheel

- Joyful Moon ~Hopi

- Little Winter Moon ~Creek

- Man Moon ~Taos

- Moon After Yule ~Cherokee

- Old Moon –Algonquin

- Quiet Moon ~Celtic, Janic

- Snow Moon ~other

- Storm Moon ~other

- Strong Cold Moon ~Sioux, Cheyenne

- Whirling Wind Moon ~Passamaquoddy

- Winter Moon ~Algonquin

- Wolf Moon ~Medieval English, Janic

The Quadrantids is an above average meteor shower, with up to 40 meteors per hour at its peak. It is thought to be produced by dust grains left behind by an extinct comet known as 2003 EH1, which was discovered in 2003. The shower runs annually from January 1-5. Best viewing will be from a dark location after midnight. Meteors will radiate from the constellation Bootes, but can appear anywhere in the sky.

Source: SeaSky

To celebrate the New Year fireballs swing in Stonehaven, Scotland.

The ceremony consists of mainly local people of all ages swinging flaming wire cages, around their heads. Each cage is filled with combustible material (each swinger has their own recipe) and has a wire handle two or three feet long, this keeps the flames well away from the swinger, but spectators can be vulnerable! At the end of the ceremony, the fireballs are tossed into the bay.

The event starts at midnight and is watched by thousands. The idea behind the ceremony is to burn off the bad spirits left from the old year so that the spirits of the New Year can come in clean and fresh.

From current research the ceremony would seem to go back from a hundred to a hundred and fifty years, but it could easily be much older.

The ceremony today lasts only around twenty to thirty minutes but in the past it could last an hour or more. Then, some of the swingers would swing their fireball for a few yards and then stop outside a house that was occupied by someone that they knew. They would drop their fireball at the curbside and pop in for their ‘New Year’! After a while they would come out, pick up their ‘ball’ and swing on down to the next house, and so on. As quite a number of the swingers would have had many relatives and friends staying in area it could take some time to get from one end of the street to the other!

In the early years, according to the newspaper reports, it would seem that it was mainly the male youths of the older ‘fisher’ town that were involved in the custom but once into the sixties the newspaper reports are of older men and women being involved as well.

In Scotland, the last day of the year is called Hogmanay, the word children use to ask for their traditional present of an oatmeal cake (which is why this is also called Cake Day). Traditionally, children in small towns would wander about town, particularly in the more affluent neighborhoods, visiting their neighbors of the better class, crying at their doors, “Hogmanay!” or sometimes the following rhyme:

In Scotland, the last day of the year is called Hogmanay, the word children use to ask for their traditional present of an oatmeal cake (which is why this is also called Cake Day). Traditionally, children in small towns would wander about town, particularly in the more affluent neighborhoods, visiting their neighbors of the better class, crying at their doors, “Hogmanay!” or sometimes the following rhyme:

Hogmanay, trollolay,

Gie’s of your white bread

and none of your gray!

In obedience to which call, they are served each with an oaten cake. Immediately after midnight it is traditional to sing Robert Burns’ “Auld Lang Syne”

“Should auld acquaintance be forgot and never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot and auld lang syne

For auld lang syne, my dear, for auld lang syne,

We’ll take a cup o kindness yet, for auld lang syne.”

Fireworks and fire festivals are still common across Scotland, as are parties and celebrations of all kinds. There are many customs, both national and local, associated with Hogmanay. The most widespread national custom is the practice of ‘first-footing’ which starts immediately after midnight. This involves being the first person to cross the threshold of a friend or neighbor and often involves the giving of symbolic gifts such as salt (less common today), coal, shortbread, whisky, and black bun (a rich fruit cake) intended to bring different kinds of luck to the householder. Food and drink (as the gifts) are then given to the guests.

This may go on throughout the early hours of the morning and well into the next day (although modern days see people visiting houses well into January). The first-foot is supposed to set the luck for the rest of the year. Traditionally, tall dark men are preferred as the first-foot. And of course, the entire spirit of a Hogmanay party is to welcome both friends and strangers with warm hospitality and of course lots of kissing all-around!

It’s believed that Hogmanay originated with the invading Vikings who celebrated the passing of the winter solstice with much revelry, but the roots of Hogmanay perhaps reach back to the celebration of the winter solstice among the Norse, as well as incorporating customs from the Gaelic New Year’s celebration of Samhain.

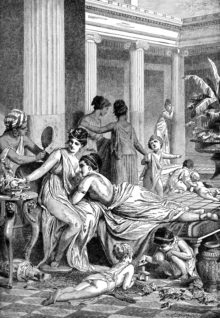

In Rome, winter solstice evolved into the ancient celebration of Saturnalia, a great winter festival, where people celebrated completely free of restraint and inhibition. The Vikings celebrated Yule, which later contributed to the Twelve Days of Christmas, or the “Daft Days” as they were sometimes called in Scotland. The winter festival went underground with the Protestant Reformation and ensuing years, but re-emerged near the end of the 17th century

Each area of Scotland often developed its own particular Hogmanay ritual.

An example of a local Hogmanay custom is the fireball swinging that takes place in Stonehaven, Aberdeenshire in north-east Scotland. This involves local people making up ‘balls’ of chicken wire filled with old news paper, dried sticks, old cotton rags, and other dry flammable material up to a diameter of 60 cm. Each ball has approximately 1 m of wire, chain or nonflammable rope attached.

An example of a local Hogmanay custom is the fireball swinging that takes place in Stonehaven, Aberdeenshire in north-east Scotland. This involves local people making up ‘balls’ of chicken wire filled with old news paper, dried sticks, old cotton rags, and other dry flammable material up to a diameter of 60 cm. Each ball has approximately 1 m of wire, chain or nonflammable rope attached.

As the Old Town House bell sounds to mark the new year, the balls are set alight and the swingers set off up the High Street from the Mercat Cross to the Cannon and back, swinging their burning ball around their head as they go for as many times as they and their fireball last. At the end of the ceremony any fireballs that are still burning are cast into the harbor.

Many people enjoy this display, which is more impressive in the dark than it would be during the day. As a result large crowds flock to the town to see it, with 12,000 attending the 2007/2008 event. In recent years, additional attractions have been added to entertain the crowds as they wait for midnight, such as fire poi, a pipe band, street drumming and a firework display after the last fireball is cast into the sea. The festivities are now streamed live over the Internet.

Another example of a pagan fire festival is the burning the clavie which takes place in the town of Burghead in Moray.In the east coast fishing communities and Dundee, first-footers used to carry a decorated herring while in Falkland in Fife, local men would go in torchlight procession to the top of the Lomond Hills as midnight approached. Bakers in St Andrews would bake special cakes for their Hogmanay celebration (known as ‘Cake Day’) and distribute them to local children.

In Glasgow and the central areas of Scotland, the tradition is to hold Hogmanay parties involving singing, dancing, the eating of steak pie or stew, storytelling and consumption of copious amounts of alcohol, which usually extend into the daylight hours of January 1.

Institutions also had their own traditions. For example, among the Scottish regiments, the officers had to wait on the men at special dinners while at the bells, the Old Year is piped out of barrack gates. The sentry then challenges the new escort outside the gates: ‘Who goes there?’ The answer is ‘The New Year, all’s well.’

An old custom in the Highlands, which has survived to a small extent and seen some degree of revival, is to celebrate Hogmanay with the saining (Scots for ‘protecting, blessing’) of the household and livestock. This is done early on New Year’s morning with copious, choking clouds of smoke from burning juniper branches, and by drinking and then sprinkling ‘magic water’ from ‘a dead and living ford’ around the house (‘a dead and living ford’ refers to a river ford which is routinely crossed by both the living and the dead). After the sprinkling of the water in every room, on the beds and all the inhabitants, the house is sealed up tight and the burning juniper carried through the house and byre.

The smoke is allowed to thoroughly fumigate the buildings until it causes sneezing and coughing among the inhabitants. Then all the doors and windows are flung open to let in the cold, fresh air of the new year. The woman of the house then administers ‘a restorative’ from the whisky bottle, and the household sits down to their New Year breakfast.

Collected from various sources

The sixth day of Christmas (Dec 30) is the day of “Bringing in the Boar.” Two traditions honor the importance of the boar at Solstice tide. In Scandinavia, Frey, the god of sunshine, rode across the sky on his golden-bristled boar. Gulli-burstin, who was seen as a solar image, his spikes representing the rays of the sun.

In the ancient Norse tradition, the intention was to gain favor from Frey in the new year. The boar’s head with an apple in his mouth was carried into the banquet hall on a gold or silver dish to the sounds of trumpets and the songs of minstrels.

In Scandinavia and England Saint Stephen (whose feast day is Dec 26) is shown as tending to horses and bringing a boar’s head to a Yuletide banquet. Christmas ham is an old tradition in Sweden and may have originated as a winter solstice boar sacrifice to Freyr.

Here’s a song from 1607:

The Boar is dead,

Lo, here is his head,

What man could have done more

Than his head off to strike,

Meleager like.

And bring it as I do before.

His living spoiled,

Where good men toiled,

Which makes kind Ceres sorry;

But now, dead and drawn,

he is very good brawn,

And we have brought it for ye.

Then set down the swineherd,

The foe of the vineyard,

Let Baccus crown his fall;

Let this boar’s head and mustard,

Stand for pig,goose and custard,

And so ye are welcome all.

From: The Winter Solstice and other sources.

The Feast of Fools, the fifth day of Christmas, (Dec 29), is a day when the normal order of things was ceremonially reversed, has been neglected for a long while – unfortunately, as it could well serve in our own times as a safe way of letting off steam. Essentially, it allowed people who were restricted from even the most casual of pleasure by the Church, to act in an abandoned way. It was also a time of festivity that was both part of, and sometimes even superseded, Christmas.

So, why not celebrate the Feast of Fools by having your own party where things get reversed, where your guests are invited to act as foolish as they can? Here are some ideas:

- Invite your guests to wear silly clothes

- Provide a box of silly or outrageous accessories – hats, shoes, wigs, gloves… use your imagination

- Have everyone paint their faces, or fingernails in wild colors (men as well as women)

- Organize a food fight or a pie throwing contest.

- Provide helium balloons so every one can talk funny.

For a great party game ask your guests to each write down a forfeit – an action that involves something very silly such as shaving with real cream, singing the words of one song to the tune of another, juggling with oranges – whatever they like. Then each guest should pull out a forfeit from the hat and do their best to obey the instruction.

If you are alone, you can still act the fool. Here are some suggestions:

- Make goofy faces at yourself in the mirror

- Wear your own clothes inside out and backwards

- Make a video or other recording of yourself laughing hysterically (fake it until you make it).

Above all, let this be a day of joyful fun and blissful games…

From: The Winter Solstice

Feast of the Holy Innocents, also called Childermas, or Innocents’ Day, festival celebrated in the Christian churches in the West on December 28 and in the Eastern churches on December 29 and commemorating the massacre of the children by King Herod in his attempt to kill the infant Jesus (Matthew 2:16–18). These children were regarded by the early church as the first martyrs, but it is uncertain when the day was first kept as a saint’s day. At first it may have been celebrated with Epiphany, but by the 5th century it was kept as a separate festival. In Rome it was a day of fasting and mourning.

It was one of a series of days known as the Feast of Fools, and the last day of authority for boy bishops. Parents temporarily abdicated authority. In convents and monasteries the youngest nun and monk were allowed to act as abbess and abbot for the day. These customs, which mocked religion, were condemned by the Council of Basel in 1431.

In medieval England the children were reminded of the mournfulness of the day by being whipped in bed in the morning; this custom survived into the 17th century. See Dyzymas Day.

The day is still observed as a feast day and, in Roman Catholic countries, as a day of merrymaking for children.

Source: Britannica.com

St Stephen’s Day, celebrated every year on 26 December, draws together a number of solstice traditions. We have already learned of the ancient practice of hunting the wren, the King of all birds (Day of the Wren), and of displaying the tiny corpse around the villages throughout Britain and Ireland. The origins of this custom probably date back to the time when kings were slaughtered after a year in office – and in France up until the seventeenth century the first person to kill and display the body of the wren was chosen king for a day at the time of the Feast of Fools.

St Stephen’s Day, celebrated every year on 26 December, draws together a number of solstice traditions. We have already learned of the ancient practice of hunting the wren, the King of all birds (Day of the Wren), and of displaying the tiny corpse around the villages throughout Britain and Ireland. The origins of this custom probably date back to the time when kings were slaughtered after a year in office – and in France up until the seventeenth century the first person to kill and display the body of the wren was chosen king for a day at the time of the Feast of Fools.

St. Stephen himself, according to legend, was once a servant of the biblical King Herod. When he saw the star of the nativity he sought to know more of the Child of Wonder born in the stable, and as a result changed his allegiance to a new king.

The association of the wren killing with St. Stephen’s Day may well derive from a legend of the saint’s visit to Scandinavia. In this story Stephen, having been captured by soldiers, was about to make his escape when the wren uttered its noisy song and awoke his guards – for which reason the wren is said to be unlucky and it is, indeed, considered a misguided act to kill the bird on any other day of the year.

St. Stephen’s Day in Wales is known as Gŵyl San Steffan. One ancient Welsh custom, discontinued in the 19th century, included bleeding of livestock and “holming” by beating with holly branches of late risers and female servants. The ceremony reputedly brought good luck.

St. Stephen’s Day (Sant Esteve) is a traditional Catalan holiday. It is celebrated with a big meal including canelons. These are stuffed with the ground remaining meat from the escudella i carn d’olla, turkey, or capó of the previous day.

Stephanitag is a public holiday in mainly Catholic Austria. In the Archdiocese of Vienna, the day of patron saint St. Stephen is even celebrated on a Sunday within the Octave of Christmas, the feast of the Holy Family. Similar to the adjacent regions of Bavaria, numerous ancient customs still continued to this day, such as ceremonial horseback rides and blessing of horses, or the “stoning” drinking ritual celebrated by young men after attending church service.

Another old tradition was parades with singers and people dressed in Christmas suits. At some areas these parades were related to checking forthcoming brides. Stephen’s Day used to be a popular day for weddings as well. These days a related tradition is dances of Stephen’s Day which are held in several restaurants and dance halls.

In Finland the most well known tradition linked to the day is “the ride of Stephen’s Day” which refers to a sleigh ride with horses. These merry rides along village streets were seen in contrast to the silent and pious mood of the preceding Christmas days. This tradition more than likely relates to the following legend about this saint, who is generally called the first Christian martyr.

The story is as follows:

St Stephen is said to have reached Sweden, and to have established a church there from which he rode forth to preach and teach the Christian message. To enable him to travel the great distances through often inhospitable country he had a string of five horses two red, two white, and one dappled. Whenever one of these became tired Stephen would simply mount another. However, as he was traveling through a particularly deep stretch of forest, he was set upon by brigands, who killed him and tied his body to the back of an unbroken colt. This beast, bearing the saint’s body, galloped all the way back to Stephen’s home. His grave there subsequently became a place of pilgrimage and perhaps because of the association with horses, sick beasts were brought there for healing. Stephen is still known as the patron saint of horses to this day.

The themes of St. Stephen’s day, then, have to do with death and resurrection and animals. The former makes it particularly appropriate that it is on this day that the Mummer plays are most often performed.

From: The Winter Solstice

The wren, the wren, The king of all birds,

On St. Stephen’s Day Is caught in the furze.

One of the most remarkable and dramatic Solstice customs involving animals is the Hunting of the Wren, which traditionally takes place on Boxing Day or St. Stephen’s Day. The custom lasted longest in Wales and the Isle of Man and still takes place today in Ireland. A description from 1840 describes it thus:

For some weeks preceding Christmas, crowds of village boys may be seen peering into hedges, in search of the tiny wren; and when one is discovered the whole assemble and give wager chase until they have slain the little bird. In the hunt the utmost excitement prevail; shouting, screeching, and rushing, all sorts of missiles are flung at the puny mark… From bush to bush, from hedge to hedge, is the wren pursued until bagged with as much pride and pleasure as the cock of the woods by the more ambitious sportsman… On the anniversary of St. Stephen the enigma is explained. Attached to a huge holly bush, elevated on a pole, the bodies of several little wrens are borne about… through the streets in procession… And every now and then stopping before some popular house and there singing the Wren song.

Various versions of this song have survived. Here is a typical one:

The wren, the wren, the king of all birds,

On St. Stephen’s Day was caught in the furze;

Though his body is small, his family is great,

So if it please your honor, give us a treat.

On Christmas day I turned a spit;

I burned my finger, I feel it yet.

Up with the kettle, down with the pan.

Give us some money to bury the wren.

The antiquity of this rather barbaric custom is clear enough. At one time the Wren, the “king of all birds,” must have represented the dying year king and was sacrificed on his behalf for the good of the land. The following story from Scotland suggest the reason for this rather plain little bird being addressed as King.

The Parliament of Birds:

At a gathering of birds, it was decided to elect a king by seeing which could fly the highest, and nearest to the sun. The eagle’s broad strong wings bore it higher than any other. It was about to acclaim its prowess, when it became aware of a “whirr-chuck” sound – the little wren had flown yet higher than the eagle, because it was cheekily perched on it’s back.

For many years during the 18th and 19th centuries, the Irish Wren Boys were accompanied by masked guisers, including the ubiquitous lair bhan or White Mare. Nowadays, due in part to a shortage of wrens and to a somewhat more bird-conscious awareness, they are seldom hunted. Although the Wren Boys still circulate in Ireland, they no longer kill a wren, but proceed from house to house with a decorated cage.

Here is a different wren song sung by the guisers in Pembrokeshire, England, where the custom is no longer practiced, but the sacredness of the bird is remembered:

Joy, health, love and peace be all here in this place.

By your leave we will sing concerning our king.

Our king is well dressed, in silks of the best,

In ribbons so rare, no king can compare.

We have traveled many miles, over hedges and stiles,

In search of our king, until you we bring.

Old Christmas is past, Twelfth Night is the last,

And we bid you adieu, great joy to the new.

It is not of the newborn king of Winter, the Wondrous Child they are speaking, but King Wren, who is remembered in a curious song from Oxfordshire, that manages to encapsulate the more ancient significance of the custom.

From: The Winter Solstice

Art by: Cathy Johnson

In Athens and other parts of ancient Greece, there is a month that corresponds to roughly December/January that is named Poseideon for the sea-god Poseidon. The Poseidonia of Aegina may have taken place in the same month. Presumably on or around the Winter Solstice.

In Athens and other parts of ancient Greece, there is a month that corresponds to roughly December/January that is named Poseideon for the sea-god Poseidon. The Poseidonia of Aegina may have taken place in the same month. Presumably on or around the Winter Solstice.

There were 16 days of feasting with rites of Aphrodite concluding the festival. Like the Roman festival of Saturnalia, the Poseidonia became so popular it was extended so that Athenaeus makes it 2 months long.

Poseidon as savior of ships, protector of those who voyage in ships, and God of the lapping waters both salt and fresh important for agriculture, is thanked for the many gifts that came from faraway places that were likely given at that time. The immense trade and distribution was nearly all through shipping, relatively little overland, whether it be perfume from Cyprus or pottery from Corinth.

It is interesting today that Agios Nikolaos (Saint Nikolas) is the Patron Saint of seafarers in the Orthodox Church. Celebrating Poseidon’s Festival seems to be lost in modern practice. It likely entailed bonfires, feasting, cutting of trees (probably decorated), and very likely gift giving. As God of begetting, that aspect was not forgotten.

The most complete account of the festival is Noel Robertson’s article Poseidon’s Festival at the Winter Solstice, The Classical Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 34, No. 1. (1984), pp. 1-16:

“The record shows that Poseidon was once worshiped in every part of Greece as a god of general importance to the community.”

“The festival falls near the winter solstice, and the ritual business marked by jollity and license, belongs to the general type of solstice festival known the world over. At Poseidon’s festival, however, the sportive conduct has a definite purpose; this purpose arises from the fundamental agrarian background if Mediterranean society, and may bring us close to the origin of solstice festivals.”

“It has scarcely been noticed that festivals of Poseidon, more than those of any other Greek deity, fall at just this time of year; yet the evidence is extensive.”

“The festival Poseidea and some of the rites in question are often claimed for Poseidon the sea-god, but at this season sailing is furthest from one’s mind, and fishing on the shore is by no means an overriding concern. Such details as we have point elsewhere, to Poseidon as the god of fresh water who fructifies Demeter’s fields.”

One of Poseidon’s epithets is prosklystios, ‘of the lapping water’. He is also invoked as Poseidon phytalmios which implies natural fertility and human procreation. There are also implications in the legends that imply bonfires at the winter solstice.

Noel Robertson concludes:

“…the celebrants feast to satiety, then turn to lascivious teasing. What is the ritual purpose of such conduct? It obviously suits Poseidon’s mythical reputation as the most lustful of gods, who far surpasses Apollo and Zeus in the number of his liaisons and his offspring. Poseidon the seducer is the god of springs and rivers; his women typically succumb while bathing or drawing water; the type of the river god is a rampant bull. But the ritual likewise treats Poseidon as a procreant force; witness the epithets phytalmios, genesios, pater, etc. as interpreted above. The myths and the ritual reflect the same belief. The rushing waters are a proponent male power, just as the fields which they fertilize are a prolific female. Both water and the fields, both Poseidon and Demeter, can be made to operate by sympathetic magic. The rites of our winter festival rouse Poseidon and bring the rushing waters…”

It is interesting that that Theophrastus tells us that the silver fir was important in ship building, especially for masts. The ‘tannenbaum’ is a silver fir. It is also interesting to compare with the Roman Saturnalia which may very well have borrowed from the Poseidea.