Weather Watching

St. Swithin was a beloved ninth-century bishop of Winchester, England, who requested that he be buried in the churchyard–some say to be close to the common people, whom he loved; some say so that he could enjoy God’s gift of rain for all eternity. When he died in 862, his request was honored.

About 100 years later, however, it was deemed unseemly that so holy a man should rest in a common grave. On July 15, the saint’s feast day, the people attempted to enshrine his remains in his church.

Legend has it, however, that St. Swithin caused torrential rains to fall for 40 days, until the intended transfer was abandoned. This is the source of a very old Scottish weather proverb regarding rain on July 15:

“St. Swithin’s Day if thou dost rain,

For forty days it will remain.”

Source: Almanac.com

Vidovdan (St. Vitus Day) is one of the important religious holidays for the Serbs. It’s annually observed on 28 June (Gregorian Calendar), or 15 June according to the Julian calendar, in use by the Serbian Orthodox Church to venerate St. Vitus. It is an important part of Serb ethnic and Serbian national identity.

Observation of this feast is connected with the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. According to the Serbian Orthodox tradition, the Serbian national identity was founded on the day, when the Ottoman Empire defeated Serbia in the Battle of Kosovo and slew prince Lazar. Ruling sultan of the Ottoman Empire was killed on the same day by Serbian knight Miloš Obilić.

Serbs consider Vidovdan a very important day, that is why many historic events in Serbia took place on June 28, for instance, signing of the Treaty of Versailles (1919), proclamation of Serbian constitution (1921), Slobodan Milošević’s deportation to the International Criminal Tribunal, etc.

In the late Middle Ages, people in Germany and countries such as Latvia celebrated the feast of Vitus by dancing before his statue. This dancing became popular and the name “Saint Vitus Dance” was given to the neurological disorder Sydenham’s chorea. It also led to Vitus being considered the patron saint of dancers and of entertainers in general.

It is also a day for weather watching:

“If St. Vitus’ Day be rainy weather,

It will rain for 30 days together.”

About St Vitus:

There are no reliable facts about existence of Saint Vitus. According to Christian legend, Vitus was the son of Roman senator from Sicily. He converted to Christianity under influence of his mentor. Satin Vitus died as a martyr during the persecution of Christians by Roman Emperors Diocletian and Maximian.

Vitus is considered the patron saint of actors, comedians, dancers, and epileptics, similarly to Genesius of Rome. He is also said to protect against lightning strikes, animal attacks and oversleeping.

Sources: Wikipedia and Any Day Guide

Good weather in “Flaming June” is necessary if there is to be a good harvest. Country weather lore states:

- If June with bright sun is blessed, for harvest, we will thank the Goddess.

- If June be sunny, harvest comes early.

- A cold and wet June ruins the rest of the year.

- It is said that if it rains on 27 June, then it will rain for the next seven weeks.

- A wet June makes a dry September.

- A dripping June brings all things in tune.

- If swallows fly near the ground in June, it is a sign of coming rain.

- Bats flying on a June evening are a sign of hot, dry weather the next day.

- A calm June puts the farmer in tune.

- June damp and warm, does the farmer no harm.

- Rain on St Vitus’ Day (June 15), brings rain for 30 days in a row.

According to country lore, it was also claimed that summer doesn’t actually begin until the elder is in flower.

Information collected from: various sources

I found this account of Mother March in an old book about Bulgaria, published in 1877. I love the way they used to celebrate the month of March. It occurs to me that it might be fun and informative to watch the weather this month and assign certain days to certain people and see what happens.

The month of March, which falls in the Spring equinox is called by the Bulgarians, Baba Mart, Old Mother March, and is the only female month of the year, the others being considered as masculine. March in Bulgaria is like April in England, inconstant and capricious, alternating between storms and sunshine; and it is here specially dedicated to the fair sex, who during its continuance enjoy complete idleness, doing no work, and asserting a sort of temporary superiority over their husbands, which sometimes even goes to the length of administering a thrashing, without fear of reprisal.

In order not to displease Baba Mart, the women do not even smear the floors of their houses with clay (a work which is usually performed every week), wash, weave, or spin; for if they were to do so Baba Mart would give no rain during the year, and lightning would infallibly strike the house in which she had been thus insulted.

There are certain clever old women who, knowing where Baba Mart resides, pay her a visit, and from her information assign to each of the married women a day of the month on which the weather will be according to the character of the lady whose day it is; thus, if Mrs. Dimitri gets the 1st of March, it will be fine, with perhaps a warm and gentle shower or two, for she is an amiable and soft-hearted woman, a little give to shedding unnecessary tears upon any pretext. Mrs. Tanaz is a loud-voiced shrew, so her day will be made up of wind, black clouds, snow, and heavy rain. “Don’t go out shooting tomorrow, Chelibi, for it is the day of Kodja Keraz’s wife, and she has such an awful temper that the weather is sure to be horrible.”

When a woman is assigned a day for the first time, her character is judged by the state of the weather; fortunately this system is not extended to young ladies on their promotion, or many a match might be broken off by an inopportune storm in the month of March.

Found in: Twelve Years study of the Eastern Question in Bulgaria

In ancient Greece, on the 16th and 17th of January, there was held a festival in which offerings were made to the Wind Gods of the eight directions.

Black lambs were offered as sacrifices to the destructive winds, and white ones to favourable or good winds. Boreas (North Wind) had a temple on the river Ilissus in Attica, and between Titane and Sicyon there was an altar of the winds, upon which a priest offered a sacrifice to the winds once in every year. Zephyrus (West Wind) had an altar on the sacred road to Eleusis.

If you are not big on animal sacrifices, you might consider the following:

- Singing or playing The Winds Four Quarters

- Doing a Ritual to the North Wind (since it is January)

- Learn how to use the four winds in magick.

- Practice some windy magick

Alternatively, you might go outside and stand in a high place and offer a pinch of herbs or spice to each of the four winds. Something sweet to sweeten whatever might come your way, might be appropriate.

More about these Windy Gods can be found at The Powers That Be

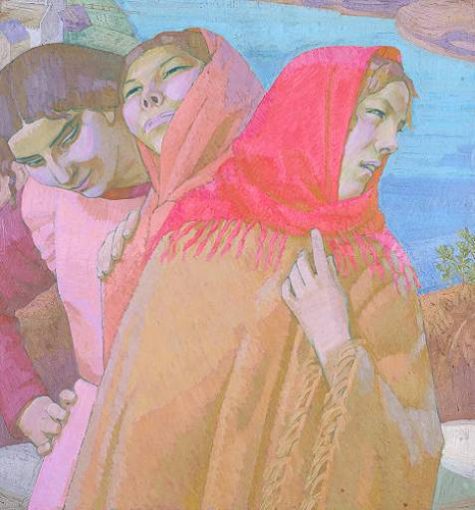

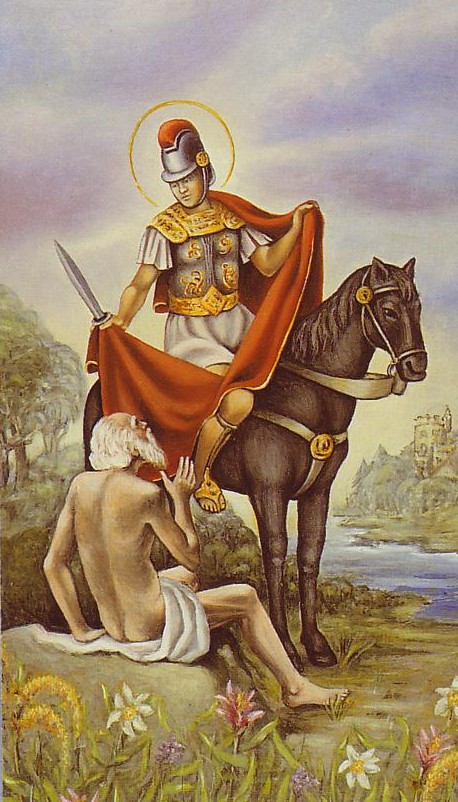

Saint Martin’s Day, also known as the Feast of Saint Martin, Martinstag or Martinmas, as well as Old Halloween and Old Hallowmas Eve, is the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours (Martin le Miséricordieux) and is celebrated on November 11 each year. This is the time when autumn wheat seeding was completed, and the annual slaughter of fattened cattle produced “Martinmas beef”. Historically, hiring fairs were held where farm laborers would seek new posts.

Saint Martin of Tours started out as a Roman soldier then was baptized as an adult and became a monk. It is understood that he was a kind man who led a quiet and simple life. The best known legend of his life is that he once cut his cloak in half to share with a beggar during a snowstorm, to save the beggar from dying from the cold. That night he dreamed that Jesus was wearing the half-cloak. Martin heard Jesus say to the angels, “Here is Martin, the Roman soldier who is now baptized; he has clothed me.”

St. Martin was known as friend of the children and patron of the poor. This holiday originated in France, then spread to the Low Countries, the British Isles, Germany, Scandinavia, and Eastern Europe. It celebrates the end of the agrarian year and the end of the harvest.

Bishop Perpetuus of Tours, who died in 490, ordered fasting three days a week from the day after Saint Martin’s Day (11 November). In the 6th century, local councils required fasting on all days except Saturdays and Sundays from Saint Martin’s Day to Epiphany (the Feast of the Three Wise Men and the star, c.f. Matthew 2: 1-12) on January 6, a period of 56 days, but of 40 days fasting, like the fast of Lent. It was therefore called Quadragesima Sancti Martini (Saint Martin’s Lent). This period of fasting was later shortened and called “Advent” by the Church.

The goose became a symbol of St. Martin of Tours because of a legend that when trying to avoid being ordained bishop he had hidden in a goose pen, where he was betrayed by the cackling of the geese. St. Martin’s feast day falls in November, when geese are ready for killing.

St. Martin’s Day was an important medieval autumn feast, and the custom of eating goose spread to Sweden from France. It was primarily observed by the craftsmen and noblemen of the towns. In the peasant community, not everyone could afford to eat goose, so many ate duck or hen instead.

Martinmas

Martinmas literally means “Mass of Martin”, or the day when Catholics celebrate the Holy Catholic Mass which honors St. Martin in a special way.

Martinmas, as a date on the calendar, has two meanings: in the agricultural calendar it marks the beginning of the natural winter, but in the economic calendar it is seen as the end of autumn. The feast coincides not only with the end of the Octave of All Saints, but with harvest-time, the time when newly produced wine is ready for drinking, and the end of winter preparations, including the butchering of animals.

An old English saying is “His Martinmas will come as it does to every hog,” meaning “he will get his comeuppance” or “everyone must die”. Because of this, St. Martin’s Feast is much like the American Thanksgiving – a celebration of the earth’s bounty. Because it also comes before the penitential season of Advent, it is seen as a mini “carnivale”, with all the feasting and bonfires.

As at Michaelmas on 29 September, goose is eaten in most places. Following these holidays, women traditionally moved their work indoors for the winter, while men would proceed to work in the forests.

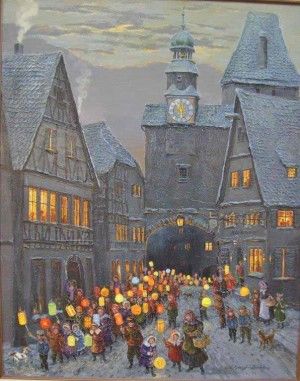

In some countries, Martinmas celebrations begin at the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of this eleventh day of the eleventh month (that is, at 11:11 am on November 11). In others, the festivities commence on St. Martin’s Eve (that is, on November 10). Bonfires are built and children carry lanterns in the streets after dark, singing songs for which they are rewarded with candy.

It is also a day of wine tasting and drinking.

Celebrations around the world:

- Austria

“Martinloben” is celebrated as a collective festival. Events include art exhibitions, wine tastings, and live music. “Martinigansl” (roasted goose) is the traditional dish of the season. In Austria St. Martin’s Day is celebrated the same way as in Germany.The nights before and on the night of Nov. 11, children walk in processions carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing Martin songs.

- Belgium

The day is celebrated on the evening of November 11 in a small part of Belgium (mainly in the east of Flanders and around Ypres). Children go through the streets with paper lanterns and candles, and sing songs about St. Martin. Sometimes, a man dressed as St. Martin rides on a horse in front of the procession.

In some areas, there is a traditional goose meal, although in West Flanders there is no specific meal; in other areas it is more a day for children, with toys brought on the night of 10 to 11 November. In the east part of the Belgian province of West Flanders, especially around Ypres, children receive presents from either their friends or family as supposedly coming from St. Martin on November 11. In other areas it is customary that children receive gifts later in the year from either their friends or family as supposedly coming from Saint Nicholas on December 5 or 6 (called Sinterklaas in Belgium and the Netherlands) or Santa Claus on December 25.

In other areas, children go from door to door, singing traditional “Sinntemette” songs, sporting a hollow beetroot with a carved face and a candle inside. Later in the evening there is a bonfire where all of them gather. At the end the beetroots are thrown into the fire, and pancakes are being served.

- Croatia, Slovenia

In Croatia, St. Martin’s Day (Martinje, Martinovanje) marks the day when the must traditionally turns to wine. The must is usually considered impure and sinful, until it is baptized and turned into wine. The baptism is performed by someone who dresses up as a bishop and blesses the wine; this is usually done by the host. Another person is chosen as the godfather of the wine. The foods traditionally eaten on the day are goose and home-made or store bought mlinci.

The biggest event in Slovenia is the St. Martin’s Day celebration in Maribor which marks the symbolic winding up of all the wine growers’ endeavours. There is the ceremonial “christening” of the new wine, and the arrival of the Wine Queen. The square Trg Leona Štuklja is filled with musicians and stalls offering autumn produce and delicacies.

- Slovakia

In Slovakia, the Feast of St. Martin is like a “2nd Birthday” for those named after this saint. Small presents or money are common gifts for this special occasion. Tradition says that if it snows on the feast of St. Martin, November 11, then St. Martin came on a white horse and there will be snow on Christmas day. However, if it doesn’t snow on this day, then St. Martin came on a dark horse and it will not snow on Christmas.

- Czech Republic

A Czech proverb connected with the Feast of St. Martin – Martin přijíždí na bílém koni (trans. “Martin is coming on a white horse”) – signifies that the first half of November in the Czech Republic is the time when it often starts to snow. St. Martin’s Day is the traditional feast day in the run-up to Advent.

Roasted goose is usually found on restaurant menus, and the Czech version of Beaujolais nouveau, Svatomartinské víno, a young wine from the recent harvest, which has recently become more widely available and popular. Wine shops and restaurants around Prague pour the first of the St. Martin’s wines at 11:11 a.m. Many restaurants offer special menus for the day, featuring the traditional roast goose.

- Denmark

In Denmark, Mortensaften, meaning the evening of St. Martin, is celebrated with traditional dinners, while the day itself is rarely recognized. (Morten is the Danish vernacular form of Martin.) The background is the same legend as mentioned above, but nowadays the goose is most often replaced with a duck due to size, taste and/or cost.

- Estonia

In Estonia, Martinmas signifies the merging of Western European customs with local Balto-Finnic pagan traditions. It also contains elements of earlier worship of the dead as well as a certain year-end celebration that predates Christianity. For centuries mardipäev (Martinmas) has been one of the most important and cherished days in the Estonian folk calendar. It remains popular today, especially among young people and the rural population. Martinmas celebrates the end of the agrarian year and the beginning of the winter period.

Among Estonians, Martinmas also marks the end of the period of All Souls, as well as the autumn period in the Estonian popular calendar when the souls of ancestors were worshiped, a period that lasted from November 1 to Martinmas (November 11). On this day children disguise themselves as men and go from door to door, singing songs and telling jokes to receive sweets.

In Southern Estonia, November is called Märtekuu after St. Martin’s Day.

- Germany

A widespread custom in Germany is bonfires on St. Martin’s eve, called “Martinsfeuer.” In recent years, the processions that accompany those fires have been spread over almost a fortnight before Martinmas. At one time, the Rhine River valley would be lined with fires on the eve of Martinmas. In the Rhineland region, Martin’s day is celebrated traditionally with a get-together during which a roasted suckling pig is shared with the neighbors.

The nights before and on the night of Nov. 11, children walk in processions carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing Martin songs. Usually, the walk starts at a church and goes to a public square. A man on horseback dressed like St. Martin accompanies the children. When they reach the square, Martin’s bonfire is lit and Martin’s pretzels are distributed.

In some regions of Germany (e.g. Rhineland or Bergisches Land) in a separate procession the children also go from house to house with their lanterns, sing songs and get candy in return.

The origin of the procession of lanterns is unclear. To some, it is a substitute for the St. Martin bonfire, which is still lit in a few cities and villages throughout Europe. It formerly symbolized the light that holiness brings to the darkness, just as St. Martin brought hope to the poor through his good deeds. Even though the tradition of the large, crackling fire is gradually being lost, the procession of lanterns is still practiced.

The tradition of the St. Martin’s goose or “Martinsgans”, which is typically served on the evening of St. Martin’s feast day following the procession of lanterns, most likely evolved from the well-known legend of St. Martin and the geese. “Martinsgans” is usually served in restaurants, roasted, with red cabbage and dumplings.

In some regions of Germany, the traditional sweet of Martinmas is “Martinshörnchen”, a pastry shaped in the form of a croissant, which recalls both the hooves of St. Martin’s horse and, by being the half of a pretzel, the parting of his mantle. In parts of western Germany these pastries are instead shaped like men (Stutenkerl or Weckmänner).

- Great Britain

In the United Kingdom, St. Martin’s Day is known as Martinmas (or sometimes Martlemass). It is one of the term days in Scotland. Many schools celebrate St. Martin’s day. Many schools are also named after St. Martin.

Martlemass beef was from cattle slaughtered at Martinmas and salted or otherwise preserved for the winter. The now largely archaic term “St. Martin’s Summer” referred to the fact that in Britain people often believed there was a brief warm spell common around the time of St. Martin’s Day, before the winter months began in earnest. A similar term that originated in America is “Indian Summer”.

- Ireland

In Ireland, on the eve of St. Martin’s Day, it is tradition to sacrifice a cockerel by bleeding it. The blood was collected and sprinkled on the four corners of the house. Also in Ireland, no wheel of any kind was to turn on St. Martin’s Day, because Martin was thrown into a mill stream and killed by the wheel and so it was not right to turn any kind of wheel on that day.

- Sicily

In Sicily, November is the winemaking season. On St. Martin’s Day Sicilians eat anise biscuits washed down with Moscato, Malvasia or Passito. More precisely, the hard biscuits are dipped into the Moscato. l’Estate di San Martino (Saint Martin’s Summer) is the traditional Sicilian reference to a period of unseasonably warm weather in early to mid November. Saint Martin’s Day is celebrated in a special way in a village near Messina and at a monastery dedicated to him overlooking Palermo beyond Monreale.

- Latvia

Mārtiņi (Martin’s) is traditionally celebrated by Latvians on November 10, marking the end of the preparations for winter, such as salting meat and fish, storing the harvest and making preserves. Mārtiņi also marks the beginning of masquerading and sledding, among other winter activities.

- Malta

St. Martin’s Day (Jum San Martin in Maltese) is celebrated in Malta on the Sunday nearest to November 11. Children are given a bag full of fruits and sweets associated with the feast, known by the Maltese as Il-Borża ta’ San Martin, “St. Martin’s bag”.

This bag may include walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, chestnuts, dried or processed figs, seasonal fruit (like oranges, tangerines, apples and pomegranates) and “Saint Martin’s bread roll” (Maltese: Ħobża ta’ San Martin). In old days, nuts were used by the children in their games.

There is a traditional rhyme associated with this custom:

Ġewż, Lewż, Qastan, Tin

Kemm inħobbu lil San Martin.

Walnuts, Almonds, Chestnuts, Figs

I love Saint Martin so much.

A feast is celebrated in the village of Baħrija on the outskirts of Rabat (Malta), including a procession led by the statue of Saint Martin. There is also a fair, and a show for local animals. San Anton School, a private school on the island, organises a walk to and from a cave especially associated with Martin in remembrance of the day.

- Netherlands

The day is celebrated on the evening of the 11th of November (the day Saint Martin died), where he is known as Sint-Maarten. As soon it gets dark, children up to the age of 11 or 12 (primary school age) go door to door with hand-crafted lanterns made of hollowed-out sugar beet or, more recently, paper, singing songs such as “Sinte Sinte Maarten,” hoping to receive candy in return, similar to Halloween.

In the past, poor people would visit farms on the 11th of November, to get food for the winter. In the 1600’s, the city of Amsterdam held boat races. 400 to 500 light craft, both rowing boats and sailboats, took part under the eyes of a vast crowd on the banks.

- Poland

St. Martin’s Day is celebrated mainly in the city of Poznań. On November 11, the people of Poznań buy and eat considerable amounts of “Rogale” (pronounced Ro-gah-leh), locally produced croissants, made specially for this occasion, filled with almond paste with poppy seeds, so-called “Rogal świętomarciński” or Martin Croissants or St. Martin Croissants.

Legend has it this centuries-old tradition commemorates a Poznań baker’s dream. His nighttime reveries had St. Martin entering the city on a white horse that lost its golden horseshoe. The very next morning, the baker whipped up horseshoe-shaped croissants filled with almonds, white poppy seeds and nuts, and gave them to the poor.

In recent years, competition amongst local bakeries has become fierce for producing the best “Rogale,” and very often bakeries proudly display a certificate of compliance with authentic, traditional recipes. Poznanians celebrate with a feast, specially organised by the city. There are different concerts, a St. Martin’s parade and a fireworks show.

- Portugal

In Portugal, St. Martin’s Day is commonly associated with the celebration of the maturation of the year’s wine, being traditionally the first day when the new wine can be tasted.

It is celebrated, traditionally around a bonfire, eating the magusto, chestnuts roasted under the embers of the bonfire (sometimes dry figs and walnuts), and drinking a local light alcoholic beverage called água-pé (literally “foot water”, made by adding water to the pomace left after the juice is pressed out of the grapes for wine – traditionally by stomping on them in vats with bare feet, and letting it ferment for several days), or the stronger jeropiga (a sweet liquor obtained in a very similar fashion, with aguardente added to the water). Água-pé, though no longer available for sale in supermarkets and similar outlets (it is officially banned for sale in Portugal), is still generally available in small local shops from domestic production.

Leite de Vasconcelos regarded the magusto as the vestige of an ancient sacrifice to honor the dead and stated that it was tradition in Barqueiros to prepare, at midnight, a table with chestnuts for the deceased family members to eat. The people also mask their faces with the dark wood ashes from the bonfire. A typical Portuguese saying related to Saint Martin’s Day:

É dia de São Martinho;

comem-se castanhas, prova-se o vinho.

It is St. Martin’s Day,

we’ll eat chestnuts, we’ll taste the wine.

This period is also quite popular because of the usual good weather period that occurs in Portugal in this time of year, called Verão de São Martinho (St. Martin’s Summer). It is frequently tied to the legend since Portuguese versions of St. Martin’s legend usually replace the snowstorm with rain (because snow is not frequent in most parts of Portugal, while rain is common at that time of the year) and have Jesus bringing the end of it, thus making the “summer” a gift from God.

- Spain

In Spain, St. Martin’s Day is the traditional day for slaughtering fattened pigs for the winter. This tradition has given way to the popular saying “A cada cerdo le llega su San Martín”, which translates as “Every pig gets its St Martin.” The phrase is used to indicate that wrongdoers eventually get their comeuppance.

- St. Maarten / St. Martin

In Sint Maarten, November 11 is St. Martin’s Day, not because of the same traditions as in other countries but that’s the date when the island was discovered by Christopher Columbus, in 1493. It is a public holiday on both sides to commemorate this event. Celebrations highlight tradition music, culture, and food.

- Sweden

St Martin’s Day was an important medieval autumn feast, and the custom of eating goose spread to Sweden from France. In early November, geese are ready for slaughter, and on St. Martin’s Eve, November 10, it is time for the traditional dinner of roast goose.

The custom is particularly popular in Skåne in southern Sweden, where goose farming has long been practiced, but it has gradually spread northwards. A proper goose dinner also includes apple charlotte.

- Switzerland

Its celebration has mainly remained a tradition in the Swiss Catholic region of the Ajoie in the canton of Jura. The traditional gargantuan feast, the Repas du Saint Martin, includes all the parts of freshly butchered pigs, accompanied by shots of Damassine, and lasting for at least 5 hours.

- United States

In the United States St. Martin’s Day celebrations are uncommon, and when they do happen, reflect the cultural heritage of a local community.

Many German restaurants feature a traditional menu with goose and gluhwein (a mulled red wine). St. Paul, Minnesota celebrates with a traditional lantern procession around Rice Park. The evening includes German treats and traditions that highlight the season of giving. In Dayton, Ohio the Dayton Liederkranz-Turner organization hosts a St. Martin’s Family Celebration on the weekend before with an evening lantern parade to the singing of St. Martin’s carols, followed by a bonfire.

- Other customs

The Auvergne region of central France traditionally hosts horse fairs on St. Martin’s Day.

Source: Wikipedia

January starts the year with a plethora of fun, frolicsome festivity. The new year in particular is celebrated by at least 170 nations. In terms of energy, January focuses on beginnings. It’s a time for personal renewal, starting any beloved project, and sustaining those things already in progress.Magic for health, protection, and prosperity is particularly augmented by working during this month. It’s also good time for spell work having to do with beginning and conceiving; protection; reversing spells; conserving energy by working on personal problems that involve no one else; getting your various bodies to work smoothly together for the same goals.

Weather Watching:

It is said that whatever the weather is like the first twelve days of January indicates what the weather will be like for the next twelve months. Each day equals one month in succession.

January Birth Signs

(Celtic, Nordic, Astrological, etc)

- Dec 22 to Jan19 – Sun in Capricorn

- Dec 22 to Jan 21 – Sign of the Carnation Flower

- Dec 23 to Jan 1 – Sign of the Apple Tree

- Dec 24 – Jan 21 – Sign of the Birch Tree

- Jan 1 to Jan 11 – Sign of the Fir Tree

- Jan 12 to Jan 24 – Sign of the Elm Tree

- Jan 21 and Feb 19 – Sign of the Orchid Flower

- Jan 21 to Feb 19 – Sun in Aquarius

- Jan 21 – Feb 17 – Sign of the Rowan Tree

- Jan 25 to Feb 3 – Sign of the Cypress Tree

January – the month of new beginnings. January was introduced into the Roman calendar by a legendary king of Rome, Numa Pompilius (c. 715 – 673 BCE), who named it in honor of Janus, the god of doors and openings, beginnings and endings.

Since January is reckoned as the first month of a new year, this connection with the god Janus is appropriate. It is an excellent time to work on putting aside the old and outdated in one’s personal life and making plans for new and better conditions.

When told by Roman officials to surrender the church’s valuables, St. Lawrence brought the city’s poor and sick. “Here is the church’s treasure,” he said.

Rome didn’t find this amusing, and legend says he was put to death in A.D. 258 by being roasted on a grate, although some scholars say he was more likely beheaded. In either case, folks in southern Europe still mark this day.

- It is customary there to eat only cold meat in recognition of the reputed manner of his death.

- Fair weather on St. Lawrence’s Day presages a fair autumn.

To do on Saint Lawrence’s Day:

Tonight, or especially tomorrow night and up to the dawn of August 12, if you look up at a clear sky in the Northern hemisphere, you may be blessed to see the Perseids meteor shower. This meteor shower is known as “the tears of St. Lawrence” because it is most visible at this time of year, though these streaks of light can sometimes be seen as early as 17 July and as late as 24 August.

To see St. Lawrence’s “fiery tears,” go outside after midnight, to a place as far away as possible from city lights (leave the city, if possible, and drive toward the constellation so that the city lights’ glow will be behind you). Lie down on the grass and look up and toward the North, about halfway between the constellation Perseus 3 — which will be very, very low on the horizon to the northeast — and the point directly overhead. Scan the sky elsewhere, too, but this area will be the most likely place to see the meteors.

If the sky is too cloudy or the Moon is too full for you to get a good view of the stars, you might not have any luck at all — but there will always be next year to try again!

When you see a “shooting star,” make a wish, as folklore says that wishes made when seeing such a star come true. Better yet, make the “wish” a prayer, and invoke St. Lawrence to pray it with you!

The darkness is no darkness with me,

but the night is as clear as the dawning,

that shineth more and more unto the perfect day.

~Saint Lawrence

As to foods, aside from the European custom of eating only cold meat, there is nothing else in particular associated with this day that I am aware of. However, given St. Lawrence’s mode of death, a barbecue might make for an interesting choice. Grill some meats and vegetables, have a nice cooler of beer, and prepare for a late night of star-gazing and recalling the glory of St. Lawrence! Continue reading

“These are strange and breathless days,

the dog days, when people are led to do things they are sure to be sorry for after.”

The Dog Days originally were the days when Sirius rose just before or at the same time as sunrise, which is no longer true, owing to procession of the equinoxes.

The Old Farmer’s Almanac lists the traditional period of the Dog Days as the 40 days beginning July 3rd and ending August 11th, coinciding with the ancient heliacal (at sunrise) rising of the Dog Star, Sirius. These are the days of the year with the least rainfall in the Northern Hemisphere.

These canicular days get their name from the Dog Star, Sirius, the brightest star in the constellation Canis Major. At this time of the year Sirius disappears into the Sun’s glow. Both heavenly bodies are in conjunction, rising and setting at around the same time. Ancient stargazers thought that the heat from Sirius, the brightest star in the heavens, combined with the heat of the Sun produced the hottest weather of the year! Even though Sirius is hotter than our Sun it is much too far away to warm our planet.

In Ancient Rome, the Dog Days ran from July 24th through August 24th, or, alternatively, from July 23 through August 23rd. The period was reckoned as extending from 20 days before to 20 days after the conjunction of Sirius (the dog star) and the sun.

The Romans sacrificed a brown dog at the beginning of the Dog Days to appease the rage of Sirius, believing that the star was the cause of the hot, sultry weather. In many European cultures (German, French, Italian) this period is still said to be the time of the Dog Days.

Since its rising also coincided with a time of extreme heat, the connection with hot, sultry weather was made for all time:

“Dog Days bright and clear indicate a happy year.

But when accompanied by rain, for better times our hopes are vain.”

The ancient Egyptians saw Sirius as a giver of life for it always reappeared at the time of the annual flooding of the Nile. When the star sank in the west and disappeared from the night sky, it remained hidden for 70 days before emerging in the east in the morning. This was viewed as a time of death and rebirth. The Egyptians copied this period in their funeral ceremonies. When a king died, his body was mummified, then interred in a pyramid or other tomb. By custom, burial took place 70 days after death, when the king was “reborn” in the stars.

Sirius was astronomically the foundation of their entire religious system. It was the embodiment of Isis, sister and consort of the god Osiris, who appeared in the sky as Orion. This is the period of time Sirius disappears from the sky — sequenced in the myth when Isis is hiding until the birth of her son, Horus — eventually the star reappears after Horus is born — resurrection.

On the first day of Sirius’ reappearance the ancient Egyptians expected an abundant harvest, if the star appeared bright and clear. If Sirius appeared dull and red, a poor harvest would result.

The Dog Star, Sirius is also known as our Spiritual Sun, esoterically the cosmic heart of our physical Sun. During the Dog Days when Sirius disappears into the Sun’s glowing light, it could be said that our physical Sun is embracing our Spiritual Sun! After such a celestial union a rebirth or resurrection can be expected.

Dog Days were popularly believed to be an evil time according to Brady’s Clavis Calendaria, 1813:

“the Sea boiled, the Wine turned sour, Dogs grew mad, and all other creatures became languid; causing to man, among other diseases, burning fevers, hysterics, and phrensies.”

The 1552 edition of the The Book of Common Prayer, way the “Dog Daies” begin July 6th and end August 17th. This corresponds very closely to the lectionary of the 1611 edition of the King James Bible (also called the Authorized version of the Bible) which indicates the Dog Days beginning on July 6th and ending on September 5th.

Note:

A recent reprint of the 1662 edition of the Book of Common Prayer contains no reference to the Dog Days. In the Southern Hemisphere, they typically occur in January and February, in the midst of the austral summer.

Honoring the Dog Days

- Themes: Fertility; Destiny; Time

- Symbols: Stars; Dogs

- Presiding Goddess: Sopdet

About Sopdet:

The reigning Egyptian Queen of the Constellations, Sopdet lies in Sirius, guiding the heavens and thereby human destiny. Sopdet is the foundation around which the Egyptian calendar system revolved, her star’s appearance heralding the beginning of the fertile season. Some scholars believe that the Star card of the tarot is fashioned after this goddess and her attributes.

Note: The dog days and the dog star Sirius are also associated with the Egyptian Goddess Hathor..

To Do Today:

The long, hot days of summer are known as “dog days” because they coincide with the rising of the dog star, Sirius. In ancient Egypt this was a welcome time as the Nile rose, bringing enriching water to the land. So, go outside at dawn, and welcome the Sun. Make an offering of water, and whisper a wish to Sopdet suited to her attributes and your needs. For example, if you need to be more timely or meet a deadline, she’s the perfect goddess to keep things on track.

If you’re curious about your destiny, watch the eastern region of the sky in the evening and see if any shooting stars appear. If so, this is a message from Sopdet. A star moving on your right side is a positive omen/ better days ahead. Those on the left indicate a need for caution, and those straight ahead mean things will continue on an even keel for now.

Nonetheless, seeing any shooting star means Sopdet has received your wish.

Source: Wikipedia and Almanac.com and 365 Goddess

May 15 is the feast day of Saint Sophia of Rome. On this date, Saint Sophia was regularly invoked against frosts that occurred late in the year; thus she was called kalte Sophie ‘cold Sophia’ in Germany by those who requested her aid in planting arable crops. Considered to be one of the “Ice Saints”. Sophia is also an “ice saint” in Slovenia and Central Europe, where St. Sophia’s day (“Cold Sophie”) is considered the last day of cold weather. There, Sophia is associated with rain and is nicknamed poscana Zofka ‘pissing Sophie’ or mokra Zofija ‘wet Sophia’ in folk tradition. In Czech, the Sophia is known as “Žofie, ledová žena” (Sophia, the ice-woman).

Many of the old weather rules are now forgotten. Nowadays, we rely on the weather forecasts of radio and television. According to lore, the “Ice Saints” Pankratius, Servatius and Bonifatius as well as the “Cold Sophie” are known for a cooling trend in the weather between 12th and 15th of May. For centuries this well-known rule had many gardeners align their plantings after it. Observations of weather patterns over many years have shown, however, that a drop in temperature occurs frequently only around May 20. Are the “Ice Saints” not in tune anymore? The mystery solution is found in the history of our calendar system: Pope Gregory VIII arranged a calendar reform in 1582, whereby the differences of the Julian calendar could be corrected to the sun year to a large extent.

The day of the “Cold Sophie” (May 15) was the date in the old calendar and corresponds to today’s May 22. Therefore the effects of the “Ice Saints” is felt in the time span of May 19-22. Sensitive transplants should only be put in the garden beds after this date.

Who is Saint Sophia of Rome?

According to tradition, she was a young woman of Rome who was killed for her faith during the reign of Diocletian. She was buried in the cemetery of Gordianus and Epimachus, and is venerated by the catholic church as a Christian martyr.

Notes:

- Saint Sophia of Rome is not the same as Saint Sophia the Martyr

- Read more about the Ice Saints here: Three Chilly Saints