Roman Festivals

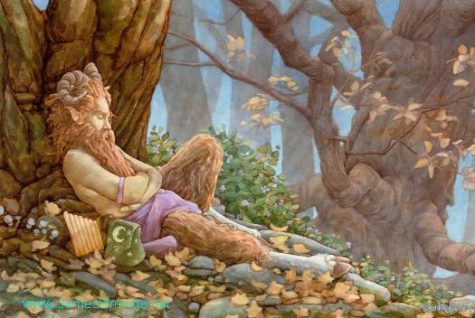

The 5thDecember was an ancient Roman festival, dedicated to Saturn’s grandson, Faunus, a god of the wildwood. The Romans celebrated Faunalia Rustica not in Rome but the countryside, so it is not registered in the calendars. However, it must have played a significant part in the lives of many Romans, especially in the early days.

In rural areas, individual farmers offered a libation of wine and sacrificed a young goat on the ancient altar made of sod. Horace recounts the peaceful holiday in one of his pastoral poems. The farmers relaxed and danced joyfully in the fields where they had labored so long and hard.

At Rome, there was a temple to Faunus on the Caelian Hill and another on Tiber Island, where the public ritual for the festival of Faunus (February 13) was conducted. However, the attempt to introduce the rural cult of Faunus into urban life was not very successful. Faunus remained chiefly a wild spirit of the countryside.

Faunus was an unpredictable deity who could cause havoc to those who farmed the land around his wildwoods. However, if correctly pacified, he could be helpful– especially during the winter season.

The name ‘Faunus’ comes from the root word favere or ‘kindly one.’ But Faunus could be anything but kindly. Dionysius also describes how his apparitions could inspire ‘terror.’ He could become an incubus, pursuing women through their dreams. He could also make life a misery for farmers around his groves.

If they were foolish enough to claim woodland as fields for their farms without first appeasing him, Faunus would appear as an apparition on the edge of the fields, haunting them.

But, by taking precautions and offering him sacrifices, it was possible to pacify and tame Faunus– for a while at least. Ovid describes how country folk would make the “the altars of rural Faunus smoke” with the sacrifices to ensure the god of the wildwood blessed their fields and livestock with fruitfulness– rather than persecuting and blighting them. The merry-making and sacrifices ensured his good offices over the winter months.

Horace’s Odes captures the essence of the festival and its rituals:

“O Faunus, thou lover of the flying nymphs, benignly traverse my borders and sunny fields and depart propitious to the young offspring of my flocks; if a tender kid fall [a victim] to thee at the completion of the year and plenty of wines be not wanting in the goblet, the companion of Venus and the ancient altar smoke with liberal perfume.

“All the cattle sport in the grassy plain when the nones of December return to thee; the village keeping holiday enjoys leisure in the fields, together with the oxen free from toil. The wolf wanders among the fearless lambs, the wood scatters its rural leaves for thee and the laborer rejoices to have beaten the hated ground in triple dance.”

The sacrifice of a goat kid and wine to the god, while villagers danced and celebrated among the autumn leaves, evoked a last festivity before the harshness of winter. But it was also essential to have Faunus’ good favor during the harsh winter season.

The country folk required Faunus’ guardianship of their flocks during the harsh winter months– as well as his good favor if they were to safely mine his woodlands for fuel and supplement their food.

Collected from various sources, including Decoded

The goddess Bona Dea also had a May festival, which is better known. The winter festival was held in December, at the home of the current senior annual Roman magistrate cum imperio, whether consul or praetor. It was hosted by the magistrate’s wife and attended by respectable matrons of the Roman elite. This winter festival is not marked on any known religious calendar but was dedicated to the public interest and supervised by the Vestals, and therefore must be considered official.

Men were not allowed to know Her name, never mind speak it, and they were also forbidden from Her secret festival. There were other taboos concerning the worship of the Bona Dea: neither wine nor myrtle were to be mentioned by name during Her secret festival, likely because they were both sacred to Her and therefore very powerful.

Shortly after 62 BC, Cicero presents it as one of very few lawful nocturnal festivals allowed to women, privileged to those of aristocratic class, and coeval with Rome’s earliest history.

Festival Rites:

The Winter festival is known primarily through Cicero’s account, supplemented by later Roman authors. First, the house was ritually cleansed of all male persons and presences, even male animals and male portraiture. Then the magistrate’s wife and her assistants made bowers of vine-leaves, and decorated the house’s banqueting hall with “all manner of growing and blooming plants” except for myrtle, whose presence and naming were expressly forbidden.

A banquet table was prepared, with a couch (pulvinar) for the goddess and the image of a snake. The Vestals brought Bona Dea’s cult image from her temple and laid it upon her couch, as an honored guest. The goddess’ meal was prepared: the entrails of a sow, sacrificed to her on behalf of the Roman people, and a libation of sacrificial wine.

The festival continued through the night, a women-only banquet with female musicians, fun and games, and wine; the last was euphemistically referred to as “milk”, and its container as a “honey jar”. The rites sanctified the temporary removal of customary constraints imposed on Roman women of all classes by Roman tradition, and underlined the pure and lawful sexual potency of virgins and matrons in a context that excluded any reference to male persons or creatures, male lust or seduction.

According to Cicero, any man who caught even a glimpse of the rites could be punished by blinding. Later Roman writers assume that apart from their different dates and locations, Bona Dea’s December and May 1 festivals were essentially the same.

Sources: Wikipedia and Thalia Took

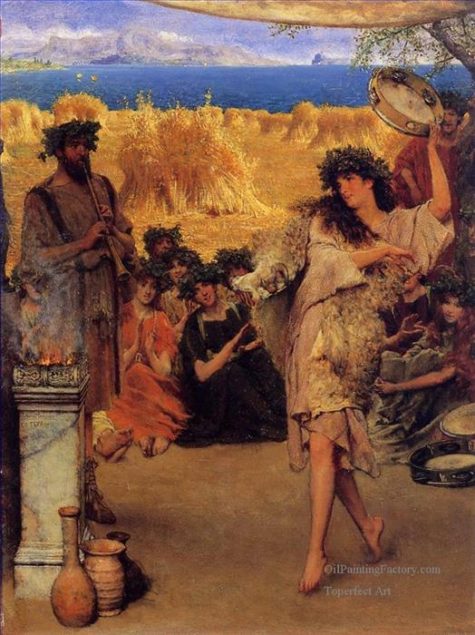

Feronia is a Latin goddess who was honored with the first fruits of the harvest in a Thanksgiving type of ritual thought to ensure a bountiful harvest for the following year. In ancient Roman religion, Feronia was a goddess associated with wildlife, fertility, health and abundance. She was worshipped in Capena, at the base of Mount Soracte, a mountain ridge in a province of ancient Rome.

Feronia is a Latin goddess who was honored with the first fruits of the harvest in a Thanksgiving type of ritual thought to ensure a bountiful harvest for the following year. In ancient Roman religion, Feronia was a goddess associated with wildlife, fertility, health and abundance. She was worshipped in Capena, at the base of Mount Soracte, a mountain ridge in a province of ancient Rome.

As the goddess who granted freedom to slaves or civil rights to the most humble part of society, she was especially honored among plebeians and freedmen. In ancient Rome Feronia’s festival was celebrated on the Ides of November, which in all likelihood was originally the day of the full moon, but eventually was settled on November 13th, or to be slightly more accurate in the Roman versions of November 13th.

Feronia’s festival, which was like a lively fair or market, was celebrated in a sacred grove where first-harvested fruits were offered to her near the foot of Mt. Soracte. Although woods and springs were especially sacred to her, and she preferred the peace of the country to the hustle of the city, Feronia also had a temple in Rome.

Feronia’s followers were thought to perform magickal acts such as fire walking. Slaves thought of her as a goddess of freedom, and they believed that, if they sat on a particular holy stone in her sacred sanctuary, they could attain freedom. One tradition says that newly freed slaves would go to her temple to receive the pileus, the special cap that signified their status as free people.

From Goddesses For Every Day and Patheos

In ancient Roman religion, the Epulum Jovis (also Epulum Iovis) was a sumptuous ritual feast offered to Jupiter on the Ides of September (September 13) and a smaller feast on the Ides of November (November 13). It was celebrated during the Ludi Romani (“Roman Games”) and the Ludi Plebeii (“Plebeian Games”).

It’s described as a kind of thanksgiving feast. People dined in honor of Minerva, Juno, and Jupiter and decorated with statues of these deities, as though the gods were among them.

The gods were formally invited, and attended in the form of statues. These were arranged on luxurious couches (pulvinaria) placed at the most honorable part of the table. Fine food was served, as if they were able to eat. The priests designated as epulones, or masters of the feast, organized and carried out the ritual, and acted as “gastronomic proxies” in eating the food.

Celebrating The Epulum Jovis:

To curry the favor and receive the considerable blessings of these gods, place statues or pictures of them on the dinner table, set places for them, and cook a simple yet delicious dinner. The layout need not be extravagant, but it should be as luxurious as possible.

Remember, these are The Gods, and they are your guests. Serve the deities food, and in all other ways treat them as honored guests. If you have any special requests, perhaps save them for tomorrow. For now, just dine and align your life with the goodwill of these powerful gods.

Be sure to have statues or other representations of the honored guests on the table. Thank them for their gifts. Here’s a toast you can use:

“For all the gifts you’ve given me,

I offer something back to thee.

A symbol of my gratitude,

A gift of drink, a gift of food.”

The ancient Romans has designated persons who acted as proxies for the Gods and ate their food for them, alternatively, their full plates could be taken outside as an offering. Wine can also be poured as a libation.

Collected from various sources

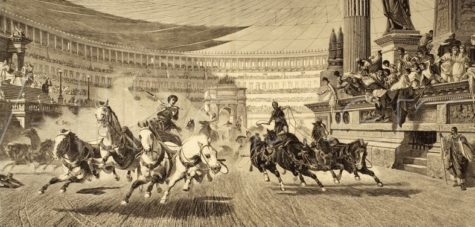

The Plebeian Games were an ancient Roman religious festival held November 4–17. The games included both theatrical performances and athletic competitions for the purpose of entertaining the common people of Rome.

The Ludi Plebeii comes from the two words ludi (meaning play, games, etc.) and plebeii (meaning a “pleb” or plebian: a commoner person as in comparison ta member of the royal or upper class). The Ludi Plebeii or Plebeian Games were an ancient Roman festival held from November (which is derived from novem or 9, because it was originally the ninth month of the year) 4th to the 17th.

The ludi or game factor of the festival was because this celebration had both theatrical performances( such as comedy, satire, tragedy plays) and athletic competitions (running, chariot racing,etc).

The importance of the Ludi Plebeii is because it represents one of the earliest national holidays of liberation. Similar to the United State’s Fourth of July or the French holiday Bastille Day, the Ludi Plebeii celebrated the plebeian’s political liberty. The Ludi Plebeii are thought to be the oldest public festival having been established roughly in 220 BCE. The great orator Cicero considered them Rome’s oldest Ludi.

The liberation that is being celebrated often varies from the tyranny of the Tarquins (an Etruscan Roman family whose history can be read on here ) or the suppression and dominance of the patricians (who were the ruling class of Rome in the struggle known as the Conflict of the Orders). Some historians even conjecture that the festival was celebrated before 220 BCE, but due to the lack of a religious calendar it was not recorded.

The dates vary for the happenings of the festival; however, they seem to follow a certain pattern:

During the Ludi Plebeii, the first ceremonial rite was a feast to Jupiter (Zeus) known as Epulum Iovis was held on November 13th (some sources say the Ides of November which is the 15th). This feast entitled the Senator to eat on the Capitoline as the public’s expense while the Roman plebeians or commoners dined in the Forum. Following the feast were several days of performance and games ( theses days vary from 9 of performance and 4 of games to smaller denominations). On the day of the Games, a great Pompa, or procession, led by statues of the Capitoline Triad, would proceed to the Circus, where Gods and men joined to watch the races. The games usually ended on the 17th of November.

A more scholarly description is as follows:

The Ludi Plebeii were, according to Pseudo-Asconius, founded to commemorate the freedom of the plebeian order after the banishment of the kings, or after the secession of the plebs to the Aventine. However, historic evidence does not support the first theory and it is likely that these games were instituted in commemoration of the reconciliation between the patricians and plebeians after the plebeians removed to either the mons sacer or, according to others, the Aventine.

The Ludi were initially conducted from November 16-18, overseen by the aediles plebis. The aediles were garbed in the robes of a triumphator, hinting at a link between the games and the ancient triumphal rites. They are almost certainly the oldest games extant, second only to the Ludi Romani held in September. Legend places the Ludi in the early history of Rome, however, the earliest mention by Livy sets the games in 216 BCE in the Circus Flaminius, built around 220 BCE and the latest record of the games can be found on the Calendar of Philocalus.

By 207 BCE the Ludi were celebrated over several days, and the Fasti Maffeiani, one of the most important surviving contemporary calendars from the Augustan era, sets the Ludi from 4-17 November.

The central focus of the Ludi was the Epulum Iovis, or feast of Iuppiter, on the Ides of November, this date being sacred to Him. The Senators ate at public expense on the Capitoline, while the Roman public dined in the Forum. The Epulum Iovis were preceded by nine days of theatrical performances and four days of racing in the Circus. On the day of the Games, a great Pompa, or procession, led by statues of the Capitoline Triad, would proceed to the Circus, where Gods and men joined to watch the races.

Titus Maccius Plautus (254-184 BCE) probably sold his first plays at the Ludi, and his play Stichus was first performed at the Ludi Plebeii. Plautus’ puns and slapstick humour were greatly valued by the Romans themselves (if not by the likes of Horace and Augustus) and influenced a much later playwright from the 16th Century: William Shakespeare.

The modern and beloved musical, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum is inspired by Plautus and contains many of his characters, including Miles Gloriosus, the braggart soldier, Pseudolus, the wily slave, and Senex, the doddering oldster.

Sources:

August 25th is the Opconsivia, (or Opeconsiva or Opalia) the harvest festival of Ops, the Roman goddess of agricultural resources and wealth, also known as Opis. The festival marked the end of harvest, with a mirror festival on December 19 concerned with the storage of the grain.

- Themes: Opportunity; Wealth; Fertility; Growth

- Symbols: Bread; Seeds; Soil

About Ops: This Italian goddess of fertile earth provides us with numerous “op-portunities” to make every day more productive. In stories, Ops motivates fruit bearing, not just in plants but also in our spirits. She also controls the wealth of the gods, making her a goddess of opulence! Works of art depict Ops with a loaf of bread in one hand, and the other outstretched, offering aid.

To Do Today:

On this day, Ops was evoked by sitting on the earth itself, where she lives in body and spirit. So, weather permitting, take yourself on a picnic lunch today. Sit with Ops and enjoy any sesame or poppy breadstuff (bagel, roll, etc.) – both types of seeds are magically aligned with Ops’s money-bringing power. If possible, keep a few of the seeds from the bread in your pocket or shoe so that after lunch, Ops’s opportunities for financial improvements or personal growth can be with you no matter where you go. And don’t forget to leave a few crumbs for the birds so they can take your magical wishes to the four corners of creation.

If the weather doesn’t cooperate, invoke Ops by getting as close to the earth as you can (sit on your floor, go into the cellar). Alternatively, eat earthy foods like potatoes, root crops, or any fruit that comes from Ops’s abundant storehouse.

More About This Festival:

The Latin word consivia (or consiva) derives from conserere (“to sow”). Opis was deemed an underworld goddess who made the vegetation grow. Since her abode was inside the earth, Ops was invoked by her worshipers while sitting, with their hands touching the ground.

Although Ops is a consort of Saturn, she was also closely associated with Consus, the protector of grains and subterranean storage bins (silos). The festival of Consus, the Consualia, was celebrated twice a year, each time preceding that of Ops: once on August 21, after the harvest, and once on December 15, after the sowing of crops was finished.

The Opiconsivia festival was superintended by the Vestals and the Flamines of Quirinus, an early Sabine god said to be the deified Romulus. The main priestess at the regia wore a white veil, characteristic of the vestal virgins. A chariot race was performed in the Circus Maximus. Horses and mules, their heads crowned with chaplets made of flowers, also took part in the celebration.

Sources: Wikipedia and 365 Goddess

On August 21, the ancient Romans celebrated the Consualia, a festival, with games, in honour of Consus, the god of secret deliberations.

It was solemnized every year in the circus, by the symbolical ceremony of uncovering an altar dedicated to the god, which was buried in the earth. This was because Romulus, who was considered the founder of the festival, was said to have discovered an altar in the earth on that spot.

The solemnity took place on the 21st of Augusta with horse and chariot races, and libations were poured into the flames which consumed the sacrifices. During these festive games, horses and mules were not allowed to do any work, and were adorned with garlands of flowers.

This festival is associated with the “Rape of the Sabine Women.” When after the building of Rome the Romans had no women, it is said, and when their suit to obtain them from the neighboring tribes was rejected, Romulus spread a report, that he had found the altar of an unknown god buried under the earth. The god was called Consus, and Romulus vowed sacrifices and a festival to him, if he succeeded in the plan he devised to obtain wives for his Romans. According to legend, it was at the first celebration of the Consualian Games that the Sabine maidens were carried off. The purpose being to populate the newly built town of Rome.

Note: Consus was eventually identified with Neptunus Equester, the alias and counterpart of Poseidon Hippios (Neptune), who was the founder of Atlantis, where, according to Plato, horses (hippos, equus) originated. Hence the connection with the animal.

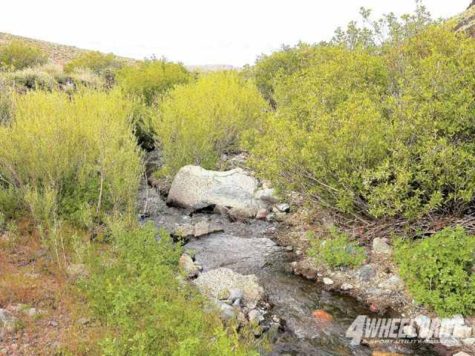

On July 25, in ancient Rome, the annual Furinalia (also spelled Furrinalia) took place in honor of the Goddess of springs, Furrina. This was the time when a drought might begin to “bite,” and the value of springs is appreciated. This is a good day to remember our vital reliance on sources of water and how important it is that they be kept clean and free of pollutants and contaminants.

In ancient Rome, this day (June 24) was known as the Festival of Fata, the Goddess of Fate and Chance. She was more commonly called Fortuna, and this day was also known as the Festival of Fortuna. The Temple of Fortuna stood on the banks of the Tiber and on this day many Romans would make a pilgrimage on foot or by boats decorated with garlands of flowers. Fortuna was especially popular with poorer Romans and the servant class, who sought the blessings that more successful Romans already had.

About Fortuna:

Initially Fortuna, the Roman goddess of abundance, was honoured as a fertility goddess, but came to symbolise abundance as the fickleness of life and luck followed the cyclic ups and downs of life. She was invoked for good luck and prosperity, or lamented to during times of hardship.

She is usually depicted holding a rudder in one hand, steering our destiny as our karmic path progresses, and/or a cornucopia (or horn of plenty) signifying the wealth that she could bring. Often she has a wheel beside her, reminding us that she is the benefactor of life, death, and the wheel of fortune.

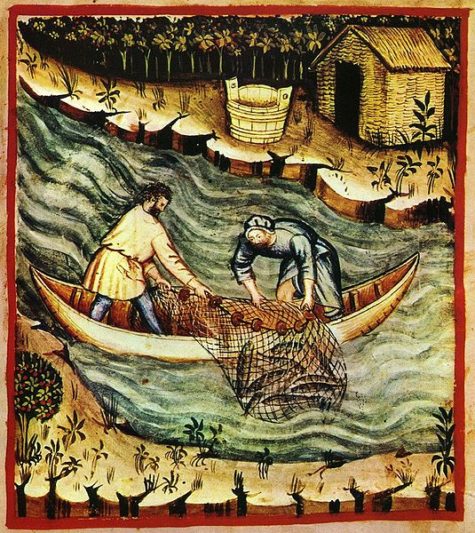

On this day, (June 17) the Romans celebrated the festival of Ludi Piscatari, festival of fishermen. Ludi Piscatari became sacred in England as a Christian Saint, renamed St. Botolph. Botolph guarded the gates of ancient English walled cities. His sigil is an Egyptian diamond, a marker still used today in navigation.