Harvest

In India a ritual was held when the the cotton boles (pods) ripen and burst. When this change in the plant occurs, it was the custom to select the largest plant in the field and having sprinkled it with buttermilk and rice water, to bind it all over with pieces of cotton taken from other plants in the field.

The selected plant is called “Mother Cotton” and after salutations are made to it, prayers are offered that the other plants may resemble it in the richness of their produce.

In other areas of India, when the cotton pods begin to burst, women go round the field, and as a kind of lustration, throw salt into it, with similar supplications that the produce may be abundant. The practice appears to be observed in somewhat similar fashion to the Ambravalia of the Romans and the Field-Litanies of the English Church.

Cotton is a kharif crop which requires 6 to 8 months to mature. Dates for this ritual vary from year to year, region to region because its time of sowing and harvesting differs in different parts of the country depending upon the climatic conditions. In Punjab and Haryana it is sown in April-May and is harvested in December-January that is before the winter frost can damage the crop.

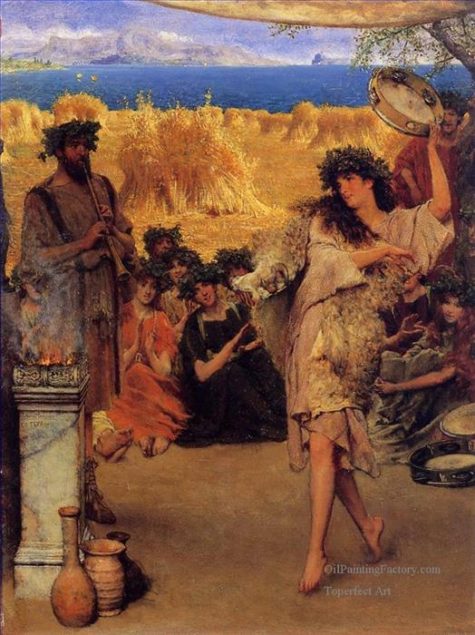

Feronia is a Latin goddess who was honored with the first fruits of the harvest in a Thanksgiving type of ritual thought to ensure a bountiful harvest for the following year. In ancient Roman religion, Feronia was a goddess associated with wildlife, fertility, health and abundance. She was worshipped in Capena, at the base of Mount Soracte, a mountain ridge in a province of ancient Rome.

Feronia is a Latin goddess who was honored with the first fruits of the harvest in a Thanksgiving type of ritual thought to ensure a bountiful harvest for the following year. In ancient Roman religion, Feronia was a goddess associated with wildlife, fertility, health and abundance. She was worshipped in Capena, at the base of Mount Soracte, a mountain ridge in a province of ancient Rome.

As the goddess who granted freedom to slaves or civil rights to the most humble part of society, she was especially honored among plebeians and freedmen. In ancient Rome Feronia’s festival was celebrated on the Ides of November, which in all likelihood was originally the day of the full moon, but eventually was settled on November 13th, or to be slightly more accurate in the Roman versions of November 13th.

Feronia’s festival, which was like a lively fair or market, was celebrated in a sacred grove where first-harvested fruits were offered to her near the foot of Mt. Soracte. Although woods and springs were especially sacred to her, and she preferred the peace of the country to the hustle of the city, Feronia also had a temple in Rome.

Feronia’s followers were thought to perform magickal acts such as fire walking. Slaves thought of her as a goddess of freedom, and they believed that, if they sat on a particular holy stone in her sacred sanctuary, they could attain freedom. One tradition says that newly freed slaves would go to her temple to receive the pileus, the special cap that signified their status as free people.

From Goddesses For Every Day and Patheos

This ritual is held on or about the day of St. Martin, a Catholic saint who was given many of Odin’s original attributes. There is strong evidence that this day (Nov 12) was originally a festival time devoted to Odin and to Cernunnos, who has many similarities to the Wanderer.

This is a time of festival for several families gathered together, each bringing food and drink for the potluck feast. Prior to the time of the rites, have a day of games and feasting. The ritual should be held out of doors if possible, with the area appropriately decorated for the season with grain, fruits, maize, vegetables, nuts, leaves and flowers. Some of the last remaining Halloween decorations may be used for a final time on this day. place banners of Odin and Freya at the northern edge of the ritual area, or some appropriate other symbols of the female and male in the Divine. Whatever symbols are used, light a candle or torch before each of them.

At the beginning of the rites, the Master of the House summons the celebrants by the blowing of a horn. When all are gathered, he and the Lady of the House light candles and give them to all of the children present; then they lead the children in procession about the perimeter of the ritual area. Upon the return of the slow procession to the starting point, they instruct the small ones to place their lamps at the edge of the ceremonial area, saying:

Place this light

At the edge of our festival

So that the Great Ones

May be with us.

When all are in readiness, the Master of the House raises his hand and says:

Friends, I now bid thee

To join in a celebration

To our patron, the wise Odin,

Known also by his other names

Of Cernunnos and St Martin

The Lady of the House then says:

We call too upon Our Blessed Lady,

The good Freya

Queen of the Harvests, giver of life

And of plenty

Since before time began.

The Master of the House calls to the assembled family members:

Let us all give thanks

For the foods of the harvest, and

For the Challenge of the hunt.

May the wise Allfather bless our homes

And bless our animals, one and all.

So mote it be.

Everyone responds:

So mote it be.

The Lady of the House then calls:

Let us all give thanks

For the fullness of this time,

For the rich promise of the harvest time,

And for the love which binds our families

And our people.

May the Holy Lady bless our homes,

Our families, and all we own.

So mote it be.

Everyone responds

So mote it be.

Both then link hands and call to the assembled family members:

May our Lord and Blessed Lady

Give blessings upon us.

Let us give joy and reveling

Before the Great Ones,

And in so doing, honor them.

This rite is ended.

The Gods be with thee.

Everyone together:

The Gods be with thee.

The children are then asked to blow out the candles that they have set about the area of the ceremony.

From The Rites of Odin

Saint Martin’s Day, also known as the Feast of Saint Martin, Martinstag or Martinmas, as well as Old Halloween and Old Hallowmas Eve, is the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours (Martin le Miséricordieux) and is celebrated on November 11 each year. This is the time when autumn wheat seeding was completed, and the annual slaughter of fattened cattle produced “Martinmas beef”. Historically, hiring fairs were held where farm laborers would seek new posts.

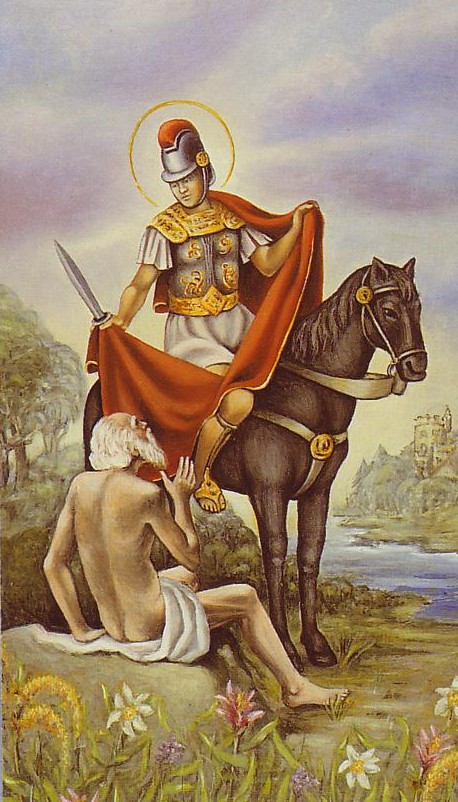

Saint Martin of Tours started out as a Roman soldier then was baptized as an adult and became a monk. It is understood that he was a kind man who led a quiet and simple life. The best known legend of his life is that he once cut his cloak in half to share with a beggar during a snowstorm, to save the beggar from dying from the cold. That night he dreamed that Jesus was wearing the half-cloak. Martin heard Jesus say to the angels, “Here is Martin, the Roman soldier who is now baptized; he has clothed me.”

St. Martin was known as friend of the children and patron of the poor. This holiday originated in France, then spread to the Low Countries, the British Isles, Germany, Scandinavia, and Eastern Europe. It celebrates the end of the agrarian year and the end of the harvest.

Bishop Perpetuus of Tours, who died in 490, ordered fasting three days a week from the day after Saint Martin’s Day (11 November). In the 6th century, local councils required fasting on all days except Saturdays and Sundays from Saint Martin’s Day to Epiphany (the Feast of the Three Wise Men and the star, c.f. Matthew 2: 1-12) on January 6, a period of 56 days, but of 40 days fasting, like the fast of Lent. It was therefore called Quadragesima Sancti Martini (Saint Martin’s Lent). This period of fasting was later shortened and called “Advent” by the Church.

The goose became a symbol of St. Martin of Tours because of a legend that when trying to avoid being ordained bishop he had hidden in a goose pen, where he was betrayed by the cackling of the geese. St. Martin’s feast day falls in November, when geese are ready for killing.

St. Martin’s Day was an important medieval autumn feast, and the custom of eating goose spread to Sweden from France. It was primarily observed by the craftsmen and noblemen of the towns. In the peasant community, not everyone could afford to eat goose, so many ate duck or hen instead.

Martinmas

Martinmas literally means “Mass of Martin”, or the day when Catholics celebrate the Holy Catholic Mass which honors St. Martin in a special way.

Martinmas, as a date on the calendar, has two meanings: in the agricultural calendar it marks the beginning of the natural winter, but in the economic calendar it is seen as the end of autumn. The feast coincides not only with the end of the Octave of All Saints, but with harvest-time, the time when newly produced wine is ready for drinking, and the end of winter preparations, including the butchering of animals.

An old English saying is “His Martinmas will come as it does to every hog,” meaning “he will get his comeuppance” or “everyone must die”. Because of this, St. Martin’s Feast is much like the American Thanksgiving – a celebration of the earth’s bounty. Because it also comes before the penitential season of Advent, it is seen as a mini “carnivale”, with all the feasting and bonfires.

As at Michaelmas on 29 September, goose is eaten in most places. Following these holidays, women traditionally moved their work indoors for the winter, while men would proceed to work in the forests.

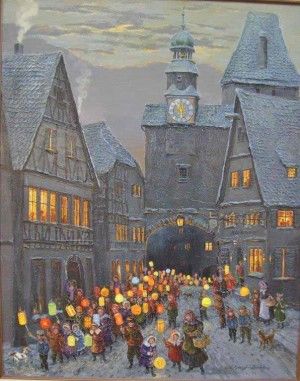

In some countries, Martinmas celebrations begin at the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of this eleventh day of the eleventh month (that is, at 11:11 am on November 11). In others, the festivities commence on St. Martin’s Eve (that is, on November 10). Bonfires are built and children carry lanterns in the streets after dark, singing songs for which they are rewarded with candy.

It is also a day of wine tasting and drinking.

Celebrations around the world:

- Austria

“Martinloben” is celebrated as a collective festival. Events include art exhibitions, wine tastings, and live music. “Martinigansl” (roasted goose) is the traditional dish of the season. In Austria St. Martin’s Day is celebrated the same way as in Germany.The nights before and on the night of Nov. 11, children walk in processions carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing Martin songs.

- Belgium

The day is celebrated on the evening of November 11 in a small part of Belgium (mainly in the east of Flanders and around Ypres). Children go through the streets with paper lanterns and candles, and sing songs about St. Martin. Sometimes, a man dressed as St. Martin rides on a horse in front of the procession.

In some areas, there is a traditional goose meal, although in West Flanders there is no specific meal; in other areas it is more a day for children, with toys brought on the night of 10 to 11 November. In the east part of the Belgian province of West Flanders, especially around Ypres, children receive presents from either their friends or family as supposedly coming from St. Martin on November 11. In other areas it is customary that children receive gifts later in the year from either their friends or family as supposedly coming from Saint Nicholas on December 5 or 6 (called Sinterklaas in Belgium and the Netherlands) or Santa Claus on December 25.

In other areas, children go from door to door, singing traditional “Sinntemette” songs, sporting a hollow beetroot with a carved face and a candle inside. Later in the evening there is a bonfire where all of them gather. At the end the beetroots are thrown into the fire, and pancakes are being served.

- Croatia, Slovenia

In Croatia, St. Martin’s Day (Martinje, Martinovanje) marks the day when the must traditionally turns to wine. The must is usually considered impure and sinful, until it is baptized and turned into wine. The baptism is performed by someone who dresses up as a bishop and blesses the wine; this is usually done by the host. Another person is chosen as the godfather of the wine. The foods traditionally eaten on the day are goose and home-made or store bought mlinci.

The biggest event in Slovenia is the St. Martin’s Day celebration in Maribor which marks the symbolic winding up of all the wine growers’ endeavours. There is the ceremonial “christening” of the new wine, and the arrival of the Wine Queen. The square Trg Leona Štuklja is filled with musicians and stalls offering autumn produce and delicacies.

- Slovakia

In Slovakia, the Feast of St. Martin is like a “2nd Birthday” for those named after this saint. Small presents or money are common gifts for this special occasion. Tradition says that if it snows on the feast of St. Martin, November 11, then St. Martin came on a white horse and there will be snow on Christmas day. However, if it doesn’t snow on this day, then St. Martin came on a dark horse and it will not snow on Christmas.

- Czech Republic

A Czech proverb connected with the Feast of St. Martin – Martin přijíždí na bílém koni (trans. “Martin is coming on a white horse”) – signifies that the first half of November in the Czech Republic is the time when it often starts to snow. St. Martin’s Day is the traditional feast day in the run-up to Advent.

Roasted goose is usually found on restaurant menus, and the Czech version of Beaujolais nouveau, Svatomartinské víno, a young wine from the recent harvest, which has recently become more widely available and popular. Wine shops and restaurants around Prague pour the first of the St. Martin’s wines at 11:11 a.m. Many restaurants offer special menus for the day, featuring the traditional roast goose.

- Denmark

In Denmark, Mortensaften, meaning the evening of St. Martin, is celebrated with traditional dinners, while the day itself is rarely recognized. (Morten is the Danish vernacular form of Martin.) The background is the same legend as mentioned above, but nowadays the goose is most often replaced with a duck due to size, taste and/or cost.

- Estonia

In Estonia, Martinmas signifies the merging of Western European customs with local Balto-Finnic pagan traditions. It also contains elements of earlier worship of the dead as well as a certain year-end celebration that predates Christianity. For centuries mardipäev (Martinmas) has been one of the most important and cherished days in the Estonian folk calendar. It remains popular today, especially among young people and the rural population. Martinmas celebrates the end of the agrarian year and the beginning of the winter period.

Among Estonians, Martinmas also marks the end of the period of All Souls, as well as the autumn period in the Estonian popular calendar when the souls of ancestors were worshiped, a period that lasted from November 1 to Martinmas (November 11). On this day children disguise themselves as men and go from door to door, singing songs and telling jokes to receive sweets.

In Southern Estonia, November is called Märtekuu after St. Martin’s Day.

- Germany

A widespread custom in Germany is bonfires on St. Martin’s eve, called “Martinsfeuer.” In recent years, the processions that accompany those fires have been spread over almost a fortnight before Martinmas. At one time, the Rhine River valley would be lined with fires on the eve of Martinmas. In the Rhineland region, Martin’s day is celebrated traditionally with a get-together during which a roasted suckling pig is shared with the neighbors.

The nights before and on the night of Nov. 11, children walk in processions carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing Martin songs. Usually, the walk starts at a church and goes to a public square. A man on horseback dressed like St. Martin accompanies the children. When they reach the square, Martin’s bonfire is lit and Martin’s pretzels are distributed.

In some regions of Germany (e.g. Rhineland or Bergisches Land) in a separate procession the children also go from house to house with their lanterns, sing songs and get candy in return.

The origin of the procession of lanterns is unclear. To some, it is a substitute for the St. Martin bonfire, which is still lit in a few cities and villages throughout Europe. It formerly symbolized the light that holiness brings to the darkness, just as St. Martin brought hope to the poor through his good deeds. Even though the tradition of the large, crackling fire is gradually being lost, the procession of lanterns is still practiced.

The tradition of the St. Martin’s goose or “Martinsgans”, which is typically served on the evening of St. Martin’s feast day following the procession of lanterns, most likely evolved from the well-known legend of St. Martin and the geese. “Martinsgans” is usually served in restaurants, roasted, with red cabbage and dumplings.

In some regions of Germany, the traditional sweet of Martinmas is “Martinshörnchen”, a pastry shaped in the form of a croissant, which recalls both the hooves of St. Martin’s horse and, by being the half of a pretzel, the parting of his mantle. In parts of western Germany these pastries are instead shaped like men (Stutenkerl or Weckmänner).

- Great Britain

In the United Kingdom, St. Martin’s Day is known as Martinmas (or sometimes Martlemass). It is one of the term days in Scotland. Many schools celebrate St. Martin’s day. Many schools are also named after St. Martin.

Martlemass beef was from cattle slaughtered at Martinmas and salted or otherwise preserved for the winter. The now largely archaic term “St. Martin’s Summer” referred to the fact that in Britain people often believed there was a brief warm spell common around the time of St. Martin’s Day, before the winter months began in earnest. A similar term that originated in America is “Indian Summer”.

- Ireland

In Ireland, on the eve of St. Martin’s Day, it is tradition to sacrifice a cockerel by bleeding it. The blood was collected and sprinkled on the four corners of the house. Also in Ireland, no wheel of any kind was to turn on St. Martin’s Day, because Martin was thrown into a mill stream and killed by the wheel and so it was not right to turn any kind of wheel on that day.

- Sicily

In Sicily, November is the winemaking season. On St. Martin’s Day Sicilians eat anise biscuits washed down with Moscato, Malvasia or Passito. More precisely, the hard biscuits are dipped into the Moscato. l’Estate di San Martino (Saint Martin’s Summer) is the traditional Sicilian reference to a period of unseasonably warm weather in early to mid November. Saint Martin’s Day is celebrated in a special way in a village near Messina and at a monastery dedicated to him overlooking Palermo beyond Monreale.

- Latvia

Mārtiņi (Martin’s) is traditionally celebrated by Latvians on November 10, marking the end of the preparations for winter, such as salting meat and fish, storing the harvest and making preserves. Mārtiņi also marks the beginning of masquerading and sledding, among other winter activities.

- Malta

St. Martin’s Day (Jum San Martin in Maltese) is celebrated in Malta on the Sunday nearest to November 11. Children are given a bag full of fruits and sweets associated with the feast, known by the Maltese as Il-Borża ta’ San Martin, “St. Martin’s bag”.

This bag may include walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, chestnuts, dried or processed figs, seasonal fruit (like oranges, tangerines, apples and pomegranates) and “Saint Martin’s bread roll” (Maltese: Ħobża ta’ San Martin). In old days, nuts were used by the children in their games.

There is a traditional rhyme associated with this custom:

Ġewż, Lewż, Qastan, Tin

Kemm inħobbu lil San Martin.

Walnuts, Almonds, Chestnuts, Figs

I love Saint Martin so much.

A feast is celebrated in the village of Baħrija on the outskirts of Rabat (Malta), including a procession led by the statue of Saint Martin. There is also a fair, and a show for local animals. San Anton School, a private school on the island, organises a walk to and from a cave especially associated with Martin in remembrance of the day.

- Netherlands

The day is celebrated on the evening of the 11th of November (the day Saint Martin died), where he is known as Sint-Maarten. As soon it gets dark, children up to the age of 11 or 12 (primary school age) go door to door with hand-crafted lanterns made of hollowed-out sugar beet or, more recently, paper, singing songs such as “Sinte Sinte Maarten,” hoping to receive candy in return, similar to Halloween.

In the past, poor people would visit farms on the 11th of November, to get food for the winter. In the 1600’s, the city of Amsterdam held boat races. 400 to 500 light craft, both rowing boats and sailboats, took part under the eyes of a vast crowd on the banks.

- Poland

St. Martin’s Day is celebrated mainly in the city of Poznań. On November 11, the people of Poznań buy and eat considerable amounts of “Rogale” (pronounced Ro-gah-leh), locally produced croissants, made specially for this occasion, filled with almond paste with poppy seeds, so-called “Rogal świętomarciński” or Martin Croissants or St. Martin Croissants.

Legend has it this centuries-old tradition commemorates a Poznań baker’s dream. His nighttime reveries had St. Martin entering the city on a white horse that lost its golden horseshoe. The very next morning, the baker whipped up horseshoe-shaped croissants filled with almonds, white poppy seeds and nuts, and gave them to the poor.

In recent years, competition amongst local bakeries has become fierce for producing the best “Rogale,” and very often bakeries proudly display a certificate of compliance with authentic, traditional recipes. Poznanians celebrate with a feast, specially organised by the city. There are different concerts, a St. Martin’s parade and a fireworks show.

- Portugal

In Portugal, St. Martin’s Day is commonly associated with the celebration of the maturation of the year’s wine, being traditionally the first day when the new wine can be tasted.

It is celebrated, traditionally around a bonfire, eating the magusto, chestnuts roasted under the embers of the bonfire (sometimes dry figs and walnuts), and drinking a local light alcoholic beverage called água-pé (literally “foot water”, made by adding water to the pomace left after the juice is pressed out of the grapes for wine – traditionally by stomping on them in vats with bare feet, and letting it ferment for several days), or the stronger jeropiga (a sweet liquor obtained in a very similar fashion, with aguardente added to the water). Água-pé, though no longer available for sale in supermarkets and similar outlets (it is officially banned for sale in Portugal), is still generally available in small local shops from domestic production.

Leite de Vasconcelos regarded the magusto as the vestige of an ancient sacrifice to honor the dead and stated that it was tradition in Barqueiros to prepare, at midnight, a table with chestnuts for the deceased family members to eat. The people also mask their faces with the dark wood ashes from the bonfire. A typical Portuguese saying related to Saint Martin’s Day:

É dia de São Martinho;

comem-se castanhas, prova-se o vinho.

It is St. Martin’s Day,

we’ll eat chestnuts, we’ll taste the wine.

This period is also quite popular because of the usual good weather period that occurs in Portugal in this time of year, called Verão de São Martinho (St. Martin’s Summer). It is frequently tied to the legend since Portuguese versions of St. Martin’s legend usually replace the snowstorm with rain (because snow is not frequent in most parts of Portugal, while rain is common at that time of the year) and have Jesus bringing the end of it, thus making the “summer” a gift from God.

- Spain

In Spain, St. Martin’s Day is the traditional day for slaughtering fattened pigs for the winter. This tradition has given way to the popular saying “A cada cerdo le llega su San Martín”, which translates as “Every pig gets its St Martin.” The phrase is used to indicate that wrongdoers eventually get their comeuppance.

- St. Maarten / St. Martin

In Sint Maarten, November 11 is St. Martin’s Day, not because of the same traditions as in other countries but that’s the date when the island was discovered by Christopher Columbus, in 1493. It is a public holiday on both sides to commemorate this event. Celebrations highlight tradition music, culture, and food.

- Sweden

St Martin’s Day was an important medieval autumn feast, and the custom of eating goose spread to Sweden from France. In early November, geese are ready for slaughter, and on St. Martin’s Eve, November 10, it is time for the traditional dinner of roast goose.

The custom is particularly popular in Skåne in southern Sweden, where goose farming has long been practiced, but it has gradually spread northwards. A proper goose dinner also includes apple charlotte.

- Switzerland

Its celebration has mainly remained a tradition in the Swiss Catholic region of the Ajoie in the canton of Jura. The traditional gargantuan feast, the Repas du Saint Martin, includes all the parts of freshly butchered pigs, accompanied by shots of Damassine, and lasting for at least 5 hours.

- United States

In the United States St. Martin’s Day celebrations are uncommon, and when they do happen, reflect the cultural heritage of a local community.

Many German restaurants feature a traditional menu with goose and gluhwein (a mulled red wine). St. Paul, Minnesota celebrates with a traditional lantern procession around Rice Park. The evening includes German treats and traditions that highlight the season of giving. In Dayton, Ohio the Dayton Liederkranz-Turner organization hosts a St. Martin’s Family Celebration on the weekend before with an evening lantern parade to the singing of St. Martin’s carols, followed by a bonfire.

- Other customs

The Auvergne region of central France traditionally hosts horse fairs on St. Martin’s Day.

Source: Wikipedia

The first full moon in November is the feast day of Baba Yaga. Baba Yaga’s themes are the harvest, rest, providence, thankfulness and cycles. Her symbols are corn sheaves, wreaths of wheat, corn, rye and wild flowers. This Lithuanian/Russian Goddess of regeneration, Baba Yaga is typically represented as the last sheaf of corn in today’s festivities – Obzinky. As both young and old, She reawakens in us an awareness of time’s ever-moving wheel, the seasons and the significance of both to our Goddess-centered magic.

- More about her here: Baba Yaga

Follow with the tradition and make or buy a wreath or bundle of corn shucks or other harvest items. Keep this in your home to inspire Baba Yaga’s providence and prosperity for everyone who lives there.

For breakfast, consume a multigrain cereal, rye bagels or wheat toast. Keep a few pieces of dried grains or toasted breads with you. This way you’ll internalize Baba Yaga’s timeliness for coping with your day more effectively and efficiently, and you’ll carry Her providence with you no matter the circumstances.

Feast on newly harvested foods, thanking Baba Yaga as the maker of your meal. Make sure you put away one piece of corn that will not be consumed today, however. Dry it and hang it up to ensure a good harvest the next year, for your garden, pocketbook or heart.

Finally, decorate your home or office with a handful of wild flowers (even dandelions qualify). Baba Yaga’s energy will follow them and you to where it’s most needed.”

Source: 365 Goddess

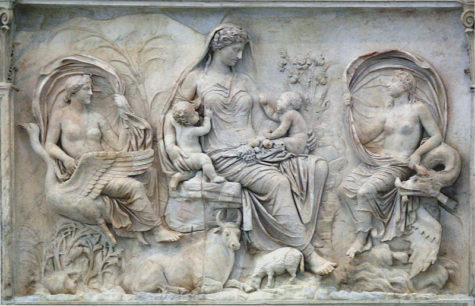

August 25th is the Opconsivia, (or Opeconsiva or Opalia) the harvest festival of Ops, the Roman goddess of agricultural resources and wealth, also known as Opis. The festival marked the end of harvest, with a mirror festival on December 19 concerned with the storage of the grain.

- Themes: Opportunity; Wealth; Fertility; Growth

- Symbols: Bread; Seeds; Soil

About Ops: This Italian goddess of fertile earth provides us with numerous “op-portunities” to make every day more productive. In stories, Ops motivates fruit bearing, not just in plants but also in our spirits. She also controls the wealth of the gods, making her a goddess of opulence! Works of art depict Ops with a loaf of bread in one hand, and the other outstretched, offering aid.

To Do Today:

On this day, Ops was evoked by sitting on the earth itself, where she lives in body and spirit. So, weather permitting, take yourself on a picnic lunch today. Sit with Ops and enjoy any sesame or poppy breadstuff (bagel, roll, etc.) – both types of seeds are magically aligned with Ops’s money-bringing power. If possible, keep a few of the seeds from the bread in your pocket or shoe so that after lunch, Ops’s opportunities for financial improvements or personal growth can be with you no matter where you go. And don’t forget to leave a few crumbs for the birds so they can take your magical wishes to the four corners of creation.

If the weather doesn’t cooperate, invoke Ops by getting as close to the earth as you can (sit on your floor, go into the cellar). Alternatively, eat earthy foods like potatoes, root crops, or any fruit that comes from Ops’s abundant storehouse.

More About This Festival:

The Latin word consivia (or consiva) derives from conserere (“to sow”). Opis was deemed an underworld goddess who made the vegetation grow. Since her abode was inside the earth, Ops was invoked by her worshipers while sitting, with their hands touching the ground.

Although Ops is a consort of Saturn, she was also closely associated with Consus, the protector of grains and subterranean storage bins (silos). The festival of Consus, the Consualia, was celebrated twice a year, each time preceding that of Ops: once on August 21, after the harvest, and once on December 15, after the sowing of crops was finished.

The Opiconsivia festival was superintended by the Vestals and the Flamines of Quirinus, an early Sabine god said to be the deified Romulus. The main priestess at the regia wore a white veil, characteristic of the vestal virgins. A chariot race was performed in the Circus Maximus. Horses and mules, their heads crowned with chaplets made of flowers, also took part in the celebration.

Sources: Wikipedia and 365 Goddess

Today, July 3rd, is the Festival of Cerridwin.

This festival honors the Welsh mother goddess, Cerridwin who embodies all lunar attributes and the energy of the harvest, specifically grains. In Celtic mythology, Cerridwin owned a cauldron of inexhaustible elixir that endowed creativity and knowledge.

The Festival of Cerridwin, coming as it does at the halfway point of the year, provides motivation to keep on keeping on. Her symbol is a pig, an animal that often represents good fortune and riches, including spiritual enrichment.

Suggestions for today:

Get creative! Use a special cup, bowl, or vase set in a special spot to represent Cerridwin’s creativity being welcome in your home. Fill the receptacle with any grain-based product (like breakfast cereal) as an offering. Whisper your desire to the grain each time you see it or walk by. At the end of the day, pour the entire bowl outside for the animals. They will bear your wish back to the goddess.

Other ideas include the following:

Today is definitely a time to consider having bacon for breakfast, a ham sandwich for lunch, or pork roast for dinner to internalize Cerridwin’s positive aspects. Vegetarians? Fill up your piggy bank with the odd change you find around your house and apply the funds to something productive to inspire Cerridwin’s blessing.

Source: 365 Goddess

From ancient times people marked the time of the return of the sun, the shortest and longest night. In olden times it was called the Feast of the Dews- Rasos. When Christianity was established in Lithuania, the name was changed to Feast of St. John, according to agrarian folk calendar, the start of haying.

The rituals of the longest day were closely related to agrarian ideas and notions. The main aim was to protect the harvest from natural calamities, evil souls, witches and mid summer visitors like drought, hail, downpours of rain and thunder.

In the 15th century, visitors to Lithuania wrote that in Vilnius, the celebrations took place in the eastern section of the city, the place of the present day “Rasos” cemetery. Fires were lit on hills and in dales. People danced, sang, ate and drank. On the Feast of St John a special role was granted to the sun. The sun is constantly mentioned in songs sung on the longest day of the year.

On this ritual day, farmers paid special attention to water’s special powers in reviving soil and making it productive. Witching on this day were carried out near and with water, people washed themselves and their animals. Special attention was paid to the dew because it revives plants at night. At sunrise farmers made their way around the fields, pulling a branch which brushed the dew to fall into the soil and cause a good harvest.

Maidens tried to get up before sunrise, collect the dew and wash their faces with it to make them bright and beautiful. They would also get up at night, go outside to wet their faces in the dew and returned to bed without wiping their faces dry. If that night they dreamt of a young man bringing them a towel, they hoped that he would be the one they would marry.

Flourishing plants were worshiped because it was believed that plants collected on the eve of the Feast of St. John posses magic powers to heal, bring luck and foretell the future. This is an ancient ritual practiced mainly by women. Roses, common daisies, especially the herb St. John’s worth and numerous grasses were some of the main plants collected at this time.

A festival pole, decorated with flowers and greenery was called “Kupolė”. Folklore shows that “Kupolė” was the Goddess of plants, living in aromatic plants, blossoms or in buds in summer and in snowdrifts in winter.

In Lithuania Minor, even in winter before the Feast of St. John, women made haste to collect medicinal herbs, with the belief that after June 24th all herbs lose their healing powers.

Girls returned to the village after picking flowers and singing, wreathed the festival post, “Kupolė”, and added colorful fluttering ribbons to it. This festival post was set at the far end of the village, near the grain fields. It had to be defended during two days and nights from young men who tried to steal it.

After saving the post, the girls removed the decorative herbs and grasses and divided them amongst themselves because these herbs had special protective powers against evil spirits and illnesses.

In some regions bunches containing nine plants were gathered by women on the eve of the Feast of St. John. Some of the plants were fed to animals before midnight, so they would be protected from evil eyes. Bunches of St. John’s worth were placed behind pictures of saints. If this bunch did not wilt fast, it was believed that it will be a lucky year.

It was believed that wreaths concentrate perpetual life’s forces and are symbols of immortality and life. There were many rites and witching’s associated with wreaths during this longest summer’s night.

Walk around three fields and gather bunches of nine flowers, twine a wreath and place it under your pillow. You will marry the man, who in your dream comes to take away the wreath. At midnight, twelve wreaths were dropped into a river and observed if they were pairing off. If no pairing off occurred, there was to be no marriage that year.

Near the river Nemunas, wreaths were dropped in the water, only when the river was calm and observed to which direction they drifted. Matchmakers would come from that direction. Releasing the wreath with the current, it will be caught by a young man, the maiden will be his. Should the wreath float away without being caught, the maiden will keep that wreath all year in her dowry chest, as a symbol of luck and health.

In the seacoast region, all during the night, young men and women twined wreaths from ferns, placed candles and set them in streams. Should both their wreaths swim together, they believed that they would marry that year.

In some regions wreaths twined during the night of the Feast of St. John were placed at crossroads with the belief that ones future will be seen in a dream.

The rites of this day continued till sunrise around bonfires. The site selected for ritual bonfires was always in the most beautiful area, on hills, on river shores and near lakes. In some regions bonfires were lit on future grain fields and under linden trees.

Those who are not fond of socializing on the eve, hurry and gather along lake shores, light bonfires, place burning poles, covered with tar into trees, so that there would be light all night long until sunrise. Special decorated wheels were lit and were rolled down hillsides, this symbolized the sun’s moving away from the earth and at the same time a request for her return.

In ancient times, the ritual fires were lit by senior priests, “vaidilos”. That fire was started with sparks coming from rubbing dried roots of medicinal herbs or from flying sparks when striking flint stones. Such fires would protect from epidemics, illnesses, poor harvests, hail and lightning.

Eggs were thrown into the fires and animals sacrificed. Later straw dolls were sacrificed in place of animals.

The ritual fires were built up to throw their light over a large area of fields, to assure a big autumn harvest. On the eve of this feast day, home fires were put out and new fires were lit using glowing coals from the ritual fires of that day.

It was believed that these ritual fires had special powers, which would protect from misfortunes, bring health and harmony to the family. It was important for newlyweds to light the fire in their hearth with the coals of the miraculous ritual fire. Such a family would be blessed, live well and in total harmony.

Jumping over fires or around it had magic meaning. Ritual bonfires cleansed both physically and psychologically. Sick adults and children were brought to the ritual fires and were pulled through the fire, with the belief that they would be healed. Jumping over the fire was carried out with the belief of making better health, increasing body strength for hard summer labors and assuring better growth of grain and flax.

Ritual fires’ ashes, smoldering coals had special powers to increase the harvest and protect it from natural calamities. The coals were dug under in fields; ashes were sprinkled on crops to assure good crop yields. To keep weeds from growing in grain fields, ritual fires’ wood splinter remains were tied to the plough share when ploughing the fields.

The feast of St. John is connected with summer weddings and their rituals which were bound to affect family living and population increases. Should a pair become friends this night, there will definitely be a wedding.

The night of June 24th is the shortest night of the year, filled with bird sounds and luxuriant vegetation. Darkness substitutes light unnoticeably, night is full of miracles due to fire reflections and shadows. It was believed that activity during this night of supernatural creatures or female witches was ill disposed towards men, animals and plants. To keep animals from their malevolent actions, animals were put in barns before sunset and were fed bread with salt for protection. Mountain ash branches and wheat sprays were hung on door posts for protection against evil spirits

In some regions clogs were placed in front of a mirror. Witches would step into the clogs and run away upset by their frightful image in the mirror.

“Šatrija” was the most famous witches’ hill, where during the night of the Feast of St. John, witches party and rage all night and invent all kinds of enchanting. This is why one could not do without “witches’ burnings”. Young people tied a barrel filled with tar and sawdust to a high pole, sprinkled it with salt so that the witches would crackle. The barrel was set on fire while the young people sang and danced merrily. Next morning the cow herd was driven through the remaining ashes, with the belief that witching’s will no longer be harmful.

During the night of the Feast of St. John, the miraculous fern bursts into bloom. It is difficult to catch sight of this bloom; however this difficulty can be overcome by going to the forest the day before, cutting down a mountain ash, pruning the branches and cutting off the top. Then pulling the tree backwards, walk about one hundred steps without looking back, toward the side to which the cut tree fell.

Look back after the hundred steps and then you will see the devil sitting stuck in the ash tree. The devil will ask for your help to get off the tree and for your help will tell you where to find the blooming fern. When you locate the blooming fern, ghosts will attack with butting horns whirlwinds will howl and cats will cry. Then take a cane made of mountain ash, draw a circle around you with it, spread a linen cloth and stop being afraid. The fern blossom will fall on the cloth. Some say that the fern bloom is like birch dust, others describe it as round and white like carp’s scale.

Prepared by: http://ausis.gf.vu.lt/eka/

Photos by: Gintaras Jaronis, Vytautas Darasevičius, Leonardas Šidlauskas and A. Kiričenko.

On December 13, the anniversary of the Temple of Tellus was celebrated along with a lectisternium (banquet) for Ceres, who embodied “growing power” and the productivity of the earth. This day was known as The Sementivaem, and was the second of two yearly festivals of Tellus Mater, the Roman earth goddess.

Very little is known about how it was celebrated. More is known about the first yearly Festival of Tellus. This festival was celebrated in honour of Tellus on the 15th of April, which was called Fordicidia or Hordicalia. You can read about it here: Fordicia – The Festival of Tellus.

In private life sacrifices were offered to Tellus at the time of sowing and at harvest-time, especially when a member of the family had died without due honors having been paid to him, for it was Tellus that had to receive the departed into her bosom. At the festival of Tellus, and when sacrifices were offered to her, the priests also prayed to a male divinity of the earth, called Tellumo.

When an oath was taken by Tellus, or the gods of the nether world, people stretched their hands downward, just as they turned them upwards in swearing by Jupiter.

About the Temple:

The Temple of Tellus was the most prominent landmark of the Carinae, a fashionable neighborhood on the Oppian Hill. It was near homes belonging to Pompey and to the Cicero family.

The temple was the result of a votum made in 268 BC by Publius Sempronius Sophus when an earthquake struck during a battle with the Picenes. Others say it was built by the Roman people. It occupied the former site of a house belonging to Spurius Cassius, which had been torn down when he was executed in 485 BC for attempting to make himself king. The anniversary (dies natalis) of its dedication was December 13.

A mysterious object called the magmentarium was stored in the temple, which was also known for a representation of Italy on the wall, either a map or an allegory.

A statue of Quintus Cicero, set up by his brother Marcus, was among those that stood on the temple grounds. Cicero claims that the proximity of his property caused some Romans to assume he had a responsibility to help maintain the temple.

Sources Wikipedia and Myth Index