Anecdotes and Stories

The Family Circle

Manfri Frederick Wood, a founding member of the Gypsy Council, and for many years its president, said that he had never met a Gypsy who had a hobby. The reason was that life itself is a hobby to the Rom. They believe in living life to its fullest, and in trying to take an intelligent interest in every job they do, they find there is no need to do anything just to “kill time.” As Wood says:

A Gaujo will go out for a walk or a drive merely for the sake of walking or driving – but a Gypsy won’t; he must have some reason for doing so; he is studying the lay of the land or the movements of the gamekeeper, or the habits of the game in the locality; or he is advertising the fact that he is in the area, where he is known and has a reputation for doing this, that, or the other job…

Even when he does appear to be at play – for instance singing and dancing, gambling, or doing a chop – it is with a view to something extra in the pocket.

The same holds true jfor the whole family. Even the children seldom play, in the strict sense of the word. They work along with the rest of the family. They may do basket work, peg-making, artificial flower making, wood carving or metal work; they may work with animals, or do dyeing, hedging, ditching, or perhaps dukkering (fortunetelling).

The family works as a unit. Boys will help their fathers with the horses and, from a very early age, will learn how to make deals. Girls similarly learn domestic chores from their mothers and also how to tell fortunes and work simple magick. There is a special closeness in a Romani family not found anywhere else.

Yet as with any family, there are times when the closeness is threatened. There are times when magick is needed, and used, to reinforce family ties.

From: Gypsy Love Magick by Raymond Buckland

Love

An Old Gypsy Story

Here is an old story about a gypsy. It’s kind of long, and a little odd, but I think it gives an interesting view of gypsies way back in the 1800’s.

KIRK YETHOLM

There are two Yetholms – Town Yetholm and Kirk Yetholm. They stand at the distance of about a quarter of a mile from each other, and between them is a valley, down which runs a small stream, called the Beaumont River, crossed by a little stone bridge. Of the town there is not much to be said. It is a long, straggling place, on the road between Morbuttle and Kelso, from which latter place it is distant about seven miles. It is comparatively modern, and sprang up when the Kirk town began to fall into decay.

Kirk Yetholm derives the first part of its name from the church, which serves for a place of worship not only for the inhabitants of the place, but for those of the town also. The present church is modern, having been built on the site of the old kirk, which was pulled down in the early part of the present century, and which had been witness of many a strange event connected with the wars between England and Scotland. It stands at the entrance of the place, on the left hand as you turn to the village after ascending the steep road which leads from the bridge.

The place occupies the lower portion of a hill, a spur of the Cheviot range, behind which is another hill, much higher, rising to an altitude of at least 900 feet. At one time it was surrounded by a stone wall, and at the farther end is a gateway overlooking a road leading to the English border, from which Kirk Yetholm is distant only a mile and a quarter; the boundary of the two kingdoms being here a small brook called Shorton Burn, on the English side of which is a village of harmless, simple Northumbrians, differing strangely in appearance, manner, and language from the people who live within a stone’s throw of them on the other side.

Kirk Yetholm is a small place, but with a remarkable look. It consists of a street, terminating in what is called a green, with houses on three sides, but open on the fourth, or right side to the mountain, towards which quarter it is grassy and steep. Most of the houses are ancient, and are built of rude stone. By far the most remarkable-looking house is a large and dilapidated building, which has much the appearance of a ruinous Spanish posada or venta.

There is not much life in the place, and you may stand ten minutes where the street opens upon the square without seeing any other human beings than two or three women seated at the house doors, or a ragged, bare-headed boy or two lying on the grass on the upper side of the Green. It came to pass that late one Saturday afternoon, at the commencement of August, in the year 1866, I was standing where the street opens on this Green, or imperfect square. My eyes were fixed on the dilapidated house, the appearance of which awakened in my mind all kinds of odd ideas. “A strange-looking place,” said I to myself at last, “and I shouldn’t wonder if strange things have been done in it.”

“Come to see the Gypsy toon, sir?” said a voice not far from me.

I turned, and saw standing within two yards of me a woman about forty years of age, of decent appearance, though without either cap or bonnet.

“A Gypsy town, is it?” said I; “why, I thought it had been Kirk Yetholm.”

Woman. – “I canna say, sir; I dinna ken whether they have or not; I have been at Yetholm several years, about my ain wee bit o’ business, and never heard them utter a word that was not either English or broad Scotch. Some people say that they have a language of their ain, and others say that they have nane, and moreover that, though they call themselves Gypsies, they are far less Gypsy than Irish, a great deal of Irish being mixed in their veins with a very little of the much more respectable Gypsy blood. It may be sae, or it may be not; perhaps your honour will find out. That’s the woman, sir, just behind ye at the door. Gud e’en. I maun noo gang and boil my cup o’tay.”

To the woman at the door I now betook myself. She was seated on the threshold, and employed in knitting. She was dressed in white, and had a cap on her head, from which depended a couple of ribbons, one on each side. As I drew near she looked up. She had a full, round, smooth face, and her complexion was brown, or rather olive, a hue which contrasted with that of her eyes, which were blue.

“There is something Gypsy in that face,” said I to myself, as I looked at her; “but I don’t like those eyes.”

“A fine evening,” said I to her at last.

“Yes, sir,” said the woman, with very little of the Scotch accent; “it is a fine evening. Come to see the town?”

“Yes,” said I; “I am come to see the town. A nice little town it seems.”

“And I suppose come to see the Gypsies, too,” said the woman, with a half smile.

“Well,” said I, “to be frank with you, I came to see the Gypsies. You are not one, I suppose?”

“Indeed I am,” said the woman, rather sharply, “and who shall say that I am not, seeing that I am a relation of old Will Faa, the man whom the woman from Haddington was speaking to you about; for I heard her mention his name?”

“Then,” said I, “you must be related to her whom they call the Gypsy queen.”

“I am, indeed, sir. Would you wish to see her?”

“By all means,” said I. “I should wish very much to see the Gypsy queen.”

“Then I will show you to her, sir; many gentlefolks from England come to see the Gypsy queen of Yetholm. Follow me, sir!”

She got up, and, without laying down her knitting-work, went round the corner, and began to ascend the hill. She was strongly made, and was rather above the middle height. She conducted me to a small house, some little way up the hill. As we were going, I said to her, “As you are a Gypsy, I suppose you have no objection to a coro of koshto levinor?”

She stopped her knitting for a moment, and appeared to consider, and then resuming it, she said hesitatingly, “No, sir, no! None at all! That is, not exactly!”

“She is no true Gypsy, after all,” said I to myself.

We went through a little garden to the door of the house, which stood ajar. She pushed it open, and looked in; then, turning round, she said: “She is not here, sir; but she is close at hand. Wait here till I go and fetch her.” She went to a house a little farther up the hill, and I presently saw her returning with another female, of slighter build, lower in stature, and apparently much older. She came towards me with much smiling, smirking, and nodding, which I returned with as much smiling and nodding as if I had known her for threescore years. She motioned me with her hand to enter the house. I did so. The other woman returned down the hill, and the queen of the Gypsies entering, and shutting the door, confronted me on the floor, and said, in a rather musical, but slightly faltering voice:

“Now, sir, in what can I oblige you?”

Thereupon, letting the umbrella fall, which I invariably carry about with me in my journeyings, I flung my arms three times up into the air, and in an exceedingly disagreeable voice, owing to a cold which I had had for some time, and which I had caught amongst the lakes of Loughmaben, whilst hunting after Gypsies whom I could not find, I exclaimed:

“Sossi your nav? Pukker mande tute’s nav! Shan tu a mumpli-mushi, or a tatchi Romany?”

Which, interpreted into Gorgio, runs thus:

“What is your name? Tell me your name! Are you a mumping woman, or a true Gypsy?”

The woman appeared frightened, and for some time said nothing, but only stared at me. At length, recovering herself, she exclaimed, in an angry tone, “Why do you talk to me in that manner, and in that gibberish? I don’t understand a word of it.”

“Gibberish!” said I; “it is no gibberish; it is Zingarrijib, Romany rokrapen, real Gypsy of the old order.”

“Whatever it is,” said the woman, “it’s of no use speaking it to me. If you want to speak to me, you must speak English or Scotch.”

“Why, they told me as how you were a Gypsy,” said I.

“And they told you the truth,” said the woman; “I am a Gypsy, and a real one; I am not ashamed of my blood.”

“If yer were a Gyptian,” said I, “yer would be able to speak Gyptian; but yer can’t, not a word.”

“At any rate,” said the woman, “I can speak English, which is more than you can. Why, your way of speaking is that of the lowest vagrants of the roads.”

“Oh, I have two or three ways of speaking English,” said I; “and when I speaks to low wagram folks, I speaks in a low wagram manner.”

“Not very civil,” said the woman.

“A pretty Gypsy!” said I; “why, I’ll be bound you don’t know what a churi is!”

The woman gave me a sharp look; but made no reply.

“A pretty queen of the Gypsies!” said I; “why, she doesn’t know the meaning of churi!”

“Doesn’t she?” said the woman, evidently nettled; “doesn’t she?”

“Why, do you mean to say that you know the meaning of churi?”

“Why, of course I do,” said the woman.

“Hardly, my good lady,” said I; “hardly; a churi to you is merely a churi.”

“A churi is a knife,” said the woman, in a tone of defiance; “a churi is a knife.”

“Oh, it is,” said I; “and yet you tried to persuade me that you had no peculiar language of your own, and only knew English and Scotch: churi is a word of the language in which I spoke to you at first, Zingarrijib, or Gypsy language; and since you know that word, I make no doubt that you know others, and in fact can speak Gypsy. Come; let us have a little confidential discourse together.”

The woman stood for some time, as if in reflection, and at length said: “Sir, before having any particular discourse with you, I wish to put a few questions to you, in order to gather from your answers whether it is safe to talk to you on Gypsy matters. You pretend to understand the Gypsy language: if I find you do not, I will hold no further discourse with you; and the sooner you take yourself off the better. If I find you do, I will talk with you as long as you like. What do you call that?” – and she pointed to the fire.

“Speaking Gyptianly?” said I.

The woman nodded.

“Whoy, I calls that yog.”

“Hm,” said the woman: “and the dog out there?”

“Gyptian-loike?” said I.

“Yes.”

“Whoy, I calls that a juggal.”

“And the hat on your head?”

“Well, I have two words for that: a staury and a stadge.”

“Stadge,” said the woman, “we call it here. Now what’s a gun?”

“There is no Gypsy in England,” said I, “can tell you the word for a gun; at least the proper word, which is lost. They have a word – yag-engro – but that is a made-up word signifying a fire-thing.”

“Then you don’t know the word for a gun,” said the Gypsy.

“Oh dear me! Yes,” said I; “the genuine Gypsy word for a gun is puschca. But I did not pick up that word in England, but in Hungary, where the Gypsies retain their language better than in England: puschca is the proper word for a gun, and not yag-engro, which may mean a fire-shovel, tongs, poker, or anything connected with fire, quite as well as a gun.”

“Puschca is the word, sure enough,” said the Gypsy. “I thought I should have caught you there; and now I have but one more question to ask you, and when I have done so, you may as well go; for I am quite sure you cannot answer it. What is Nokkum?”

“Nokkum,” said I; “nokkum?”

“Aye,” said the Gypsy; “what is Nokkum? Our people here, besides their common name of Romany, have a private name for themselves, which is Nokkum or Nokkums. Why do the children of the Caungri Foros call themselves Nokkums?”

“Nokkum,” said I; “nokkum? The root of nokkum must be nok, which signifieth a nose.”

“A-h!” said the Gypsy, slowly drawing out the monosyllable, as if in astonishment.

“Yes,” said I; “the root of nokkum is assuredly nok, and I have no doubt that your people call themselves Nokkum because they are in the habit of nosing the Gorgios. Nokkums means Nosems.”

“Sit down, sir,” said the Gypsy, handing me a chair. “I am now ready to talk to you as much as you please about Nokkum words and matters, for I see there is no danger. But I tell you frankly that had I not found that you knew as much as, or a great deal more than, myself, not a hundred pounds, nor indeed all the money in Berwick, should have induced me to hold discourse with you about the words and matters of the Brown children of Kirk Yetholm.”

I sat down in the chair which she handed me; she sat down in another, and we were presently in deep discourse about matters Nokkum. We first began to talk about words, and I soon found that her knowledge of Romany was anything but extensive; far less so, indeed, than that of the commonest English Gypsy woman, for whenever I addressed her in regular Gypsy sentences, and not in poggado jib, or broken language, she would giggle and say I was too deep for her.

I should say that the sum total of her vocabulary barely amounted to three hundred words. Even of these there were several which were not pure Gypsy words – that is, belonging to the speech which the ancient Zingary brought with them to Britain. Some of her bastard Gypsy words belonged to the cant or allegorical jargon of thieves, who, in order to disguise their real meaning, call one thing by the name of another. For example, she called a shilling a ‘hog,’ a word belonging to the old English cant dialect, instead of calling it by the genuine Gypsy term tringurushi, the literal meaning of which is three groats. Then she called a donkey ‘asal,’ and a stone ‘cloch,’ which words are neither cant nor Gypsy, but Irish or Gaelic. I incurred her vehement indignation by saying they were Gaelic. She contradicted me flatly, and said that whatever else I might know I was quite wrong there; for that neither she nor any one of her people would condescend to speak anything so low as Gaelic, or indeed, if they possibly could avoid it, to have anything to do with the poverty-stricken creatures who used it.

It is a singular fact that, though principally owing to the magic writings of Walter Scott, the Highland Gael and Gaelic have obtained the highest reputation in every other part of the world, they are held in the Lowlands in very considerable contempt. There the Highlander, elsewhere “the bold Gael with sword and buckler,” is the type of poverty and wretchedness; and his language, elsewhere “the fine old Gaelic, the speech of Adam and Eve in Paradise,” is the designation of every unintelligible jargon. But not to digress.

On my expressing to the Gypsy queen my regret that she was unable to hold with me a regular conversation in Romany, she said that no one regretted it more than herself, but that there was no help for it; and that slight as I might consider her knowledge of Romany to be, it was far greater than that of any other Gypsy on the Border, or indeed in the whole of Scotland; and that as for the Nokkums, there was not one on the Green who was acquainted with half a dozen words of Romany, though the few words they had they prized high enough, and would rather part with their heart’s blood than communicate them to a stranger.

“Unless,” said I, “they found the stranger knew more than themselves.”

“That would make no difference with them,” said the queen, “though it has made a great deal of difference with me. They would merely turn up their noses, and say they had no Gaelic. You would not find them so communicative as me; the Nokkums, in general, are a dour set, sir.”

Before quitting the subject of language it is but right to say that though she did not know much Gypsy, and used cant and Gaelic terms, she possessed several words unknown to the English Romany, but which are of the true Gypsy order. Amongst them was the word tirrehi, or tirrehai, signifying shoes or boots, which I had heard in Spain and in the east of Europe. Another was calches, a Wallachian word signifying trousers. Moreover, she gave the right pronunciation to the word which denotes a man not of Gypsy blood, saying gajo, and not gorgio, as the English Gypsies do. After all, her knowledge of Gentle Romany was not altogether to be sneezed at.

Ceasing to talk to her about words, I began to question her about the Faas. She said that a great number of the Faas had come in the old time to Yetholm, and settled down there, and that her own forefathers had always been the principal people among them. I asked her if she remembered her grandfather, old Will Faa, and received for answer that she remembered him very well, and that I put her very much in mind of him, being a tall, lusty man, like himself, and having a skellying look with the left eye, just like him.

I asked her if she had not seen queer folks at Yetholm in her grandfather’s time. “Dosta dosta,” said she; “plenty, plenty of queer folk I saw at Yetholm in my grandfather’s time, and plenty I have seen since, and not the least queer is he who is now asking me questions.”

“Did you ever see Piper Allen?” said I; “he was a great friend of your grandfather’s.”

“I never saw him,” she replied; “but I have often heard of him. He married one of our people.”

“He did so,” said I, “and the marriage-feast was held on the Green just behind us. He got a good, clever wife, and she got a bad, rascally husband. One night, after taking an affectionate farewell of her, he left her on an expedition, with plenty of money in his pocket, which he had obtained from her, and which she had procured by her dexterity. After going about four miles he bethought himself that she had still some money, and returning crept up to the room in which she lay asleep, and stole her pocket, in which were eight guineas; then slunk away, and never returned, leaving her in poverty, from which she never recovered.”

I then mentioned Madge Gordon, at one time the Gypsy queen of the Border, who used, magnificently dressed, to ride about on a pony shod with silver, inquiring if she had ever seen her. She said she had frequently seen Madge Faa, for that was her name, and not Gordon; but that when she knew her, all her magnificence, beauty, and royalty had left her; for she was then a poor, poverty-stricken old woman, just able with a pipkin in her hand to totter to the well on the Green for water. Then with much nodding, winking, and skellying, I began to talk about Drabbing bawlor, dooking gryes, cauring, and hokking, and asked if them ‘ere things were ever done by the Nokkums: and received for answer that she believed such things were occasionally done, not by the Nokkums, but by other Gypsies, with whom her people had no connection.

Observing her eyeing me rather suspiciously, I changed the subject; asking her if she had travelled much about. She told me she had, and that she had visited most parts of Scotland, and seen a good bit of the northern part of England.

“Did you travel alone?” said I.

“No,” said she; “when I travelled in Scotland I was with some of my own people, and in England with the Lees and Bosvils.”

“Old acquaintances of mine,” said I; “why only the other day I was with them at Fairlop Fair, in the Wesh.”

“I frequently heard them talk of Epping Forest,” said the Gypsy; “a nice place, is it not?”

“The loveliest forest in the world!” said I. “Not equal to what it was, but still the loveliest forest in the world, and the pleasantest, especially in summer; for then it is thronged with grand company, and the nightingales, and cuckoos, and Romany chals and chies. As for Romany-chals there is not such a place for them in the whole world as the Forest. Them that wants to see Romany-chals should go to the Forest, especially to the Bald-faced Hind on the hill above Fairlop, on the day of Fairlop Fair. It is their trysting-place, as you would say, and there they musters from all parts of England, and there they whoops, dances, and plays; keeping some order nevertheless, because the Rye of all the Romans is in the house, seated behind the door:

Romany Chalor

Anglo the wuddur

Mistos are boshing;

Mande beshello

Innar the wuddur

Shooning the boshipen.”

Roman lads

Before the door

Bravely fiddle;

Here I sit

Within the door

And hear them fiddle.

“I wish I knew as much Romany as you, sir,” said the Gypsy. “Why, I never heard so much Romany before in all my life.”

She was rather a small woman, apparently between sixty and seventy, with intelligent and rather delicate features. Her complexion was darker than that of the other female; but she had the same kind of blue eyes. The room in which we were seated was rather long, and tolerably high. In the wall, on the side which fronted the windows which looked out upon the Green, were oblong holes for beds, like those seen in the sides of a cabin. There was nothing of squalor or poverty about the place.

Wishing to know her age, I inquired of her what it was. She looked angry, and said she did not know.

“Are you forty-nine?” said I, with a terrible voice, and a yet more terrible look.

“More,” said she, with a smile; “I am sixty-eight.”

There was something of the gentlewoman in her: on my offering her money she refused to take it, saying that she did not want it, and it was with the utmost difficulty that I persuaded her to accept a trifle, with which, she said, she would buy herself some tea.

But withal there was hukni in her, and by that she proved her Gypsy blood. I asked her if she would be at home on the following day, for in that case I would call and have some more talk with her, and received for answer that she would be at home and delighted to see me. On going, however, on the following day, which was Sunday, I found the garden-gate locked and the window-shutters up, plainly denoting that there was nobody at home.

Seeing some men lying on the hill, a little way above, who appeared to be observing me, I went up to them for the purpose of making inquiries. They were all young men, and decently though coarsely dressed. None wore the Scottish cap or bonnet, but all the hat of England. Their countenances were rather dark, but had nothing of the vivacious expression observable in the Gypsy face, but much of the dogged, sullen look which makes the countenances of the generality of the Irish who inhabit London and some other of the large English towns so disagreeable. They were lying on their bellies, occasionally kicking their heels into the air. I greeted them civilly, but received no salutation in return.

“Is So-and-so at home?” said I.

“No,” said one, who, though seemingly the eldest of the party, could not have been more than three-and-twenty years of age; “she is gone out.”

“Is she gone far?” said I.

“No,” said the speaker, kicking up his heels.

“Where is she gone to?”

“She’s gone to Cauldstrame.”

“How far is that?”

“Just thirteen miles.”

“Will she be at home to-day?”

“She may, or she may not.”

“Are you of her people?” said I.

“No-h,” said the fellow, slowly drawing out the word.

“Can you speak Irish?”

“No-h; I can’t speak Irish,” said the fellow, tossing up his nose, and then flinging up his heels.

“You know what arragod is?” said I.

“No-h!”

“But you know what ruppy is?” said I; and thereupon I winked and nodded.

“No-h;” and then up went the nose, and subsequently the heels.

“Good day,” said I; and turned away; I received no counter-salutation; but, as I went down the hill, there was none of the shouting and laughter which generally follow a discomfited party. They were a hard, sullen, cautious set, in whom a few drops of Gypsy blood were mixed with some Scottish and a much larger quantity of low Irish.

Between them and their queen a striking difference was observable. In her there was both fun and cordiality; in them not the slightest appearance of either. What was the cause of this disparity? The reason was they were neither the children nor the grandchildren of real Gypsies, but only the remote descendants, whereas she was the granddaughter of two genuine Gypsies, old Will Faa and his wife, whose daughter was her mother; so that she might be considered all but a thorough Gypsy; for being by her mother’s side a Gypsy, she was of course much more so than she would have been had she sprung from a Gypsy father and a Gentile mother; the qualities of a child, both mental and bodily, depending much less on the father than on the mother. Had her father been a Faa, instead of her mother, I should probably never have heard from her lips a single word of Romany, but found her as sullen and inductile as the Nokkums on the Green, whom it was of little more use questioning than so many stones.

Nevertheless, she had played me the hukni, and that was not very agreeable; so I determined to be even with her, and by some means or other to see her again. Hearing that on the next day, which was Monday, a great fair was to be held in the neighbourhood of Kelso, I determined to go thither, knowing that the likeliest place in all the world to find a Gypsy at is a fair; so I went to the grand cattle-fair of St. George, held near the ruined castle of Roxburgh, in a lovely meadow not far from the junction of the Teviot and Tweed; and there sure enough, on my third saunter up and down, I met my Gypsy.

We met in the most cordial manner – smirks and giggling on her side, smiles and nodding on mine. She was dressed respectably in black, and was holding the arm of a stout wench, dressed in garments of the same colour, who she said was her niece, and a rinkeni rakli. The girl whom she called rinkeni or handsome, but whom I did not consider handsome, had much of the appearance of one of those Irish girls, born in London, whom one so frequently sees carrying milk-pails about the streets of the metropolis.

By the bye, how is it that the children born in England of Irish parents account themselves Irish and not English, whilst the children born in Ireland of English parents call themselves not English but Irish? Is it because there is ten times more nationality in Irish blood than in English? After the smirks, smiles, and salutations were over, I inquired whether there were many Gypsies in the fair. “Plenty,” said she, “plenty Tates, Andersons, Reeds, and many others. That woman is an Anderson – yonder is a Tate,” said she, pointing to two common-looking females.

“Have they much Romany?” said I.

“No,” said she, “scarcely a word.”

“I think I shall go and speak to them,” said I.

“Don’t,” said she; “they would only be uncivil to you. Moreover, they have nothing of that kind – on the word of a rawnie they have not.”

I looked in her eyes; there was nothing of hukni in them, so I shook her by the hand; and through rain and mist, for the day was a wretched one, trudged away to Dryburgh to pay my respects at the tomb of Walter Scott, a man with whose principles I have no sympathy, but for whose genius I have always entertained the most intense admiration.

from ~ “Romano Lavo-Lil” by George Borrow

In The Days We Went A-Gipsying

When as a lad I trudged along in the brick-yards, now more than forty years ago, I remember most vividly that the popular song of the employees of that day was

“When lads and lasses in their best

Were dress’d from top to toe,

In the days we went a-gipsying

A long time ago;

In the days we went a-gipsying,

A long time ago.”

Every “brick-yard lad” and “brick-yard wench” who would not join in singing these lines was always looked upon as a “stupid donkey,” and the consequence was that upon all occasions, when excitement was needed as a whip, they were “struck up;” especially would it be the case when the limbs of the little brick and clay carrier began to totter and were “fagging up.” When the task-master perceived the “gang” had begun to “slinker” he would shout out at the top of his voice, “Now, lads and wenches, strike up with the:

“‘In the days we went a-gipsying, a long time ago.’”

And as a result more work was ground out of the little English slave. Those words made such an impression upon me at the time that I used to wonder what “gipsying” meant.

Somehow or other I imagined that it was connected with fortune-telling, thieving and stealing in one form or other, especially as the lads used to sing it with “gusto” when they had been robbing the potato field to have “a potato fuddle,” while they were “oven tenting” in the night time. Roasted potatoes and cold turnips were always looked upon as a treat for the “brickies.”

I have often vowed and said many times that I would, if spared, try to find out what “gipsying” really was. It was a puzzle I was always anxious to solve. Many times I have been like the horse that shies at them as they camp in the ditch bank, half frightened out of my wits, and felt anxious to know either more or less of them. From the days when carrying clay and loading canal-boats was my toil and “gipsying” my song, scarcely a week has passed without the words

“When lads and lasses in their best

Were dress’d from top to toe,

In the days we went a-gipsying

A long time ago,”

ringing in my ears, and at times when busily engaged upon other things, “In the days we went a-gipsying” would be running through my mind.

In meditation and solitude; by night and by day; at the top of the hill, and down deep in the dale; in the throng and battle of life; at the deathbed scene; through evil report and good report these words, “In the days we went a-gipsying,” were ever and anon at my tongue’s end. The other part of the song I quickly forgot, but these words have stuck to me ever since.

On purpose to try to find out what fortune-telling was, when in my teens I used to walk after working hours from Tunstall to Fenton, a distance of six miles, to see “old Elijah Cotton,” a well-known character in the Potteries, who got his living by it, to ask him all sorts of questions.

On purpose to try to find out what fortune-telling was, when in my teens I used to walk after working hours from Tunstall to Fenton, a distance of six miles, to see “old Elijah Cotton,” a well-known character in the Potteries, who got his living by it, to ask him all sorts of questions.

Sometimes he would look at my hands, at other times he would put my hand into his, and hold it while he was reading out of the Bible, and burning something like brimstone-looking powder—the forefinger of the other hand had to rest upon a particular passage or verse; at other times he would give me some of this yellow-looking stuff in a small paper to wear against my left breast, and some I had to burn exactly as the clock struck twelve at night, under the strictest secrecy.

The stories this fortune-teller used to relate to me as to his wonderful power over the spirits of the other world were very amusing, aye, and over “the men and women of this generation.” He was frequently telling me that he had “fetched men from Manchester in the dead of the night flying through the air in the course of an hour;” and this kind of rubbish he used to relate to those who paid him their shillings and half-crowns to have their fortunes told.

My visits lasted for a little time till he told me that he could do nothing more, as I was “not one of his sort.”

From: Gipsy Life, by George Smith, 1880

How Gypsies Became Fortune-tellers

The following is an excerpt from: Gypsy Sorcery and Fortune Telling, a book written in 1891 by Charles Leland, President of the Gypsy Lore Society in London. It’s a bit of a hard read, but I found it interesting, so I’m sharing it here:

As their peculiar perfume is the chief association with spices, so sorcery is allied in every memory to gypsies. And as it has not escaped many poets that there is something more strangely sweet and mysterious in the scent of cloves than in that of flowers, so the attribute of inherited magic power adds to the romance of these picturesque wanderers.

Both the spices and the Romany come from the far East–the fatherland of divination and enchantment. The latter have been traced with tolerable accuracy, If we admit their affinity with the Indian Dom and Domar, back to the threshold of history, or well-nigh into prehistoric times, and in all ages they, or their women, have been engaged, as if by elvish instinct, in selling enchant. merits, peddling prophecies and palmistry, and dealing with the devil generally ill a small retail way.

As it was of old so it is to-day:

Ki shan i Romani– Adoi san’ i chov’hani.

Wherever gypsies go, There the witches are, we know.

It is no great problem ill ethnology or anthropology as to how gypsies became fortune-tellers. We may find a very curious illustration of it in the wren. This is apparently as humble, modest, prosaic little fowl as exists, and as far from mystery and wickedness as an old hen. But the ornithologists of the olden time, and the myth-makers, and the gypsies who lurked and lived in the forest, knew better.

They saw how this bright-eyed, strange little creature in her elvish way slipped in and out of hollow trees and wood shade into sunlight, and anon was gone, no man knew whither, and so they knew that it was an uncanny creature, and told wonderful tales of its deeds in human form, and to-day it is called by gypsies in Germany, as in England, the witch-bird, or more briefly, chorihani, “the witch.”

Just so the gypsies themselves, with their glittering Indian eyes, slipping like the wren in and out of the shadow of the Unknown, and anon away and invisible, won for themselves the name which now they wear.

Wherever Shamanism, or the sorcery which is based on exorcising or commanding spirits, exists, its professors from leading strange lives, or from solitude or wandering, become strange and wild looking. When men have this appearance people associate with it mysterious power.

This is the case in Tartary, Africa, among the Eskimo, Lapps, or Red Indians, with all of whom the sorcerer, voodoo or medaolin, has the eye of the “fascinator,” glittering and cold as that of a serpent. So the gypsies, from the mere fact of being wanderers and out-of-doors livers in wild places, became wild-looking, and when asked if they did not associate with the devils who dwell in the desert places, admitted the soft impeachment, and being further questioned as to whether their friends the devils, fairies, elves, and goblins had not taught them how to tell the future, they pleaded guilty, and finding that it paid well, went to work in their small way to improve their “science,” and particularly their pecuniary resources. It was an easy calling; it required no property or properties, neither capital nor capitol, shiners nor shrines, wherein to work the oracle.

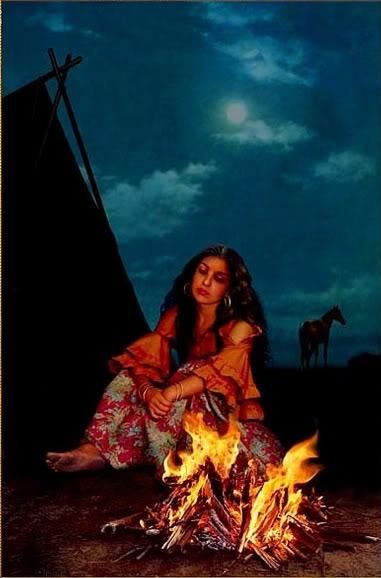

The Moon Smiles

This is a poem that talks about how both life and death are a mixture of sadness and joy.

Moonlight

O chonut asal amen

…Teochonut korhavola

teamen dikhasa

sad

kon vakarela

Kaj e phake erovimase

thaj e asamase

ka arakhadon

English Translation

The moon smiles

down on us

around the fire

we weep

wahh!

Our crying flies up

among the moonbeams floating down

heaven smells our tears

we sense the beams

If the moon is blinded we can see

who is speaking…

With one wing of tears

and one laughter

we take off to meet him.

-Rajko Durich

A Collection of Quotes

Some of these quotes are about Gypsies, some are by Gypsies. What they really show is how badly, inhumanly,and unfairly Gypsies were treated, as well as the strength they had to stand together and fight!

“No we were not always slaves; see our brothers who live in the mountains. They know nothing of chains, neck irons, whippings and hunger and thirst…Let us go free!!”

~Mateo Maximoff

“They scarcely ever stop in one place more than thirty days..they move from field to field with their oblong tents, black and low, like arabs.”

~Simeon Simeonis, a monk in Crete in 1322

“Their ears be nailed to a tree, and cutted off, and them banished the county; and if thereafter they be found again that they be hanged…the idle people calling themselves Egyptians.”

~Scottish law against vagrants, 1579

“I saw a woman guard kill four Gypsy children for eating leftover food.”

~Barbara Richter 1963

“We are people of worth, not thieves or murderers. History has played with us, thrown us down and split us up. But we must seek our destiny..by coming together as one people.”

~Jarko Jovanovic, 1978

“Well this policeman stopped my motor and asked where I live. ‘First tree I come to I can climb.’ I said”

~Gypsy Girl 1972

“It is true, as the Lovara Rom say, “Amari shib si amari zor” ‘Our language is our strength.”

~Dr Ian Hankock, a Gypsy 1975

“Gypsies express in their music their grief and their joy…Music accompanies their life from the earliest childhood until death itself.”

~Dr Jan Cibula 1978

“The greatest strength of Gypsies is their invisibility…they merge into the mass of strangers in the street.”

~Ronald Lee 1971

More to come but that’s all for now.

~Sovereign Brigand 1998

For Peace At Someone’s Death

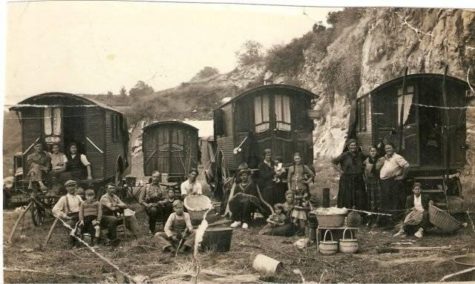

For Gypsies there is far more concern for the living than for the dead. Yet the Rom believe there must always be a family vigil prior to the death of a family member. After the death there will be the funeral, which must be followed by a proper period of mourning.

English Gypsies believe that the owl is a harbinger of death. If they hear an owl hooting away in the distance, then it means someone close to them will die. If the owl is close by, with its cries loud and clear, then the person who will die is distant.

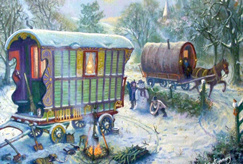

When an elderly member of the tribe is ill, and certain that he or she is going to die, work is sent out to all family members whereverthey happen to be scattered. They will immediatly return home, no matter from how far, for this is the one event that takes precedence over all others. The family members gather around the dying person’s bed, or outside around the tent or vardo.

There is always someone seated at the bedside until the death. It is a time for much socializing, with very little emotion shown regarding the dying man or woman.

Once dead, the person is caught between the world of the living and the world of the dead. He or she will stay there until buried. In order to ease the stay there, and to prepare them for the transition to the world of the dead, there is a simple ritual that is sometimes performed by the shuvani(often without the knowledge of any of the other members of the tribe).

A small fire is lit – quite separate from any cooking fire – as soon as possible after the last breath. The fire should be laid carefully so that it can be started with one light and so that it will burn for a sufficient time without having to have more fuel added. Onto the fire are thrown thyme, sage, and rosemary, in that order. The dead person’s name is chanted repeatedly as the shuvani walks backwards (widdershins, or counterclockwise) seven times around the fire, which is then left to burn itself out.

From Gypsy Love Magick

Art by Ann Falcone

Gypsy Fortune Telling

Gypsy women, as long as we have known anything of Gypsy history, have been arrant fortune-tellers. They plied fortune-telling about France and Germany as early as 1414, the year when the dusky bands were first observed in Europe, and they have never relinquished the practice. There are two words for fortune-telling in Gypsy, bocht and dukkering. Bocht is a Persian word, a modification of, or connected with, the Sanscrit bagya, which signifies ‘fate.’ Dukkering is the modification of a Wallaco-Sclavonian word signifying something spiritual or ghostly. In Eastern European Gypsy, the Holy Ghost is called Swentuno Ducos.

Gypsy women, as long as we have known anything of Gypsy history, have been arrant fortune-tellers. They plied fortune-telling about France and Germany as early as 1414, the year when the dusky bands were first observed in Europe, and they have never relinquished the practice. There are two words for fortune-telling in Gypsy, bocht and dukkering. Bocht is a Persian word, a modification of, or connected with, the Sanscrit bagya, which signifies ‘fate.’ Dukkering is the modification of a Wallaco-Sclavonian word signifying something spiritual or ghostly. In Eastern European Gypsy, the Holy Ghost is called Swentuno Ducos.

Gypsy fortune-telling is much the same everywhere, much the same in Russia as it is in Spain and in England. Everywhere there are three styles – the lofty, the familiar, and the homely; and every Gypsy woman is mistress of all three and uses each according to the rank of the person whose vast she dukkers, whose hand she reads, and adapts the luck she promises.

There is a ballad of some antiquity in the Spanish language about the Buena Ventura, a few stanzas of which translated will convey a tolerable idea of the first of these styles to the reader, who will probably with no great reluctance dispense with any illustrations of the other two:

Late rather one morning

In summer’s sweet tide,

Goes forth to the Prado

Jacinta the bride:

There meets her a Gypsy

So fluent of talk,

And jauntily dressed,

On the principal walk.

“O welcome, thrice welcome,

Of beauty thou flower!

Believe me, believe me,

Thou com’st in good hour.”

Surprised was Jacinta;

She fain would have fled;

But the Gypsy to cheer her

“O cheek like the rose-leaf!

O lady high-born!

Turn thine eyes on thy servant,

But ah, not in scorn.

“O pride of the Prado!

O joy of our clime!

Thou twice shalt be married,

And happily each time.

“Of two noble sons Thou shalt be the glad mother,

One a Lord Judge,

A Field-Marshal the other.”

Gypsy females have told fortunes to higher people than the young Countess Jacinta: Modor – of the Gypsy quire of Moscow – told the fortune of Ekatarina, Empress of all the Russias. The writer does not know what the Ziganka told that exalted personage, but it appears that she gave perfect satisfaction to the Empress, who not only presented her with a diamond ring – a Russian diamond ring is not generally of much value – but also her hand to kiss.

The writer’s old friend, Pepíta, the Gitana of Madrid, told the bahi of Christina, the Regentess of Spain, in which she assured her that she would marry the son of the King of France, and received from the fair Italian a golden ounce, the most magnificent of coins, a guerdon which she richly merited, for she nearly hit the mark, for though Christina did not marry the son of the King of France, her second daughter was married to a son of the King of France, the Duke of M-, one of the three claimants of the crown of Spain, and the best of the lot; and Britannia, the Caumli, told the good luck to the Regent George on Newmarket Heath, and received ‘foive guineas’ and a hearty smack from him who eventually became George the Fourth – no bad fellow by the by, either as regent or king, though as much abused as Pontius Pilate, whom he much resembled in one point, unwillingness to take life – the sonkaypè or gold-gift being, no doubt, more acceptable than the choomapé or kiss-gift to the Beltenebrosa, who, if a certain song be true, had no respect for gorgios, however much she liked their money:

Britannia is my nav;

I am a Kaulo Camlo;

The gorgios pen I be

A bori chovahaunie;

And tatchipen they pens,

The dinneleskie gorgies,

For mande chovahans

The luvvu from their putsies.

Britannia is my name;

I am a swarthy Lovel;

The Gorgios say I be

A witch of wondrous power;

And faith they speak the truth,

The silly, foolish fellows,

For often I bewitch

The money from their pockets.

Fortune-telling in all countries where the Gypsies are found is frequently the prelude to a kind of trick called in all Gypsy dialects by something more or less resembling the Sanscrit kuhana; for instance, it is called in Spain jojana, hokano, and in English hukni. It is practised in various ways, all very similar; the defrauding of some simple person of money or property being the object in view. Females are generally the victims of the trick, especially those of the middle class, who are more accessible to the poor woman than those of the upper. One of the ways, perhaps the most artful, will be found described in another chapter (What is The Hukni? and What is Cauring?)

From: Romano Lavo-Lil

Gypsy Names

Each gypsy had three names:

The first was a secret name whispered into the baby’s ear shortly after birth and again when the child reached puberty but never spoken aloud at any other time and never told to anyone else.

The second was a gypsy name, used between gypsies only.

The third was a local name, usually chosen to reflect the general names being given to non-gypsies in the country where the gypsy resided. This was the name the gypsy was to use publicly,with a gadje (non-gypsy), or for on official documents.