Monthly Archives: August 2017

Activate Your Money Magic

- A decorative bowl

- 5 small red candles – tealights make an excellent choice

- Cinnamin Stick – for prosperity

- Allspice – for success

- Handful of spare change.

Light the candle and allow it to burn all the way down. The next day, remove the spent candle and add any spare change that you may have accumulated. Remember to say “thank you.” Now, put the second red candle on top of the money, sprinkle the allspice, and say the charm.

Do this for five days in a row, and your money magic will be activated, empowered, recharged, and amplified.

What if you end up with so much spare change that your bowl is filled with money before the 5 days are up? Or if you absolutely need to use some of it? No worries. You can take money from the bowl, just be sure to leave at least 5 coins.

From: The Good Spell Book

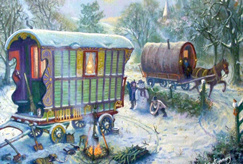

An Old Gypsy Story

Here is an old story about a gypsy. It’s kind of long, and a little odd, but I think it gives an interesting view of gypsies way back in the 1800’s.

KIRK YETHOLM

There are two Yetholms – Town Yetholm and Kirk Yetholm. They stand at the distance of about a quarter of a mile from each other, and between them is a valley, down which runs a small stream, called the Beaumont River, crossed by a little stone bridge. Of the town there is not much to be said. It is a long, straggling place, on the road between Morbuttle and Kelso, from which latter place it is distant about seven miles. It is comparatively modern, and sprang up when the Kirk town began to fall into decay.

Kirk Yetholm derives the first part of its name from the church, which serves for a place of worship not only for the inhabitants of the place, but for those of the town also. The present church is modern, having been built on the site of the old kirk, which was pulled down in the early part of the present century, and which had been witness of many a strange event connected with the wars between England and Scotland. It stands at the entrance of the place, on the left hand as you turn to the village after ascending the steep road which leads from the bridge.

The place occupies the lower portion of a hill, a spur of the Cheviot range, behind which is another hill, much higher, rising to an altitude of at least 900 feet. At one time it was surrounded by a stone wall, and at the farther end is a gateway overlooking a road leading to the English border, from which Kirk Yetholm is distant only a mile and a quarter; the boundary of the two kingdoms being here a small brook called Shorton Burn, on the English side of which is a village of harmless, simple Northumbrians, differing strangely in appearance, manner, and language from the people who live within a stone’s throw of them on the other side.

Kirk Yetholm is a small place, but with a remarkable look. It consists of a street, terminating in what is called a green, with houses on three sides, but open on the fourth, or right side to the mountain, towards which quarter it is grassy and steep. Most of the houses are ancient, and are built of rude stone. By far the most remarkable-looking house is a large and dilapidated building, which has much the appearance of a ruinous Spanish posada or venta.

There is not much life in the place, and you may stand ten minutes where the street opens upon the square without seeing any other human beings than two or three women seated at the house doors, or a ragged, bare-headed boy or two lying on the grass on the upper side of the Green. It came to pass that late one Saturday afternoon, at the commencement of August, in the year 1866, I was standing where the street opens on this Green, or imperfect square. My eyes were fixed on the dilapidated house, the appearance of which awakened in my mind all kinds of odd ideas. “A strange-looking place,” said I to myself at last, “and I shouldn’t wonder if strange things have been done in it.”

“Come to see the Gypsy toon, sir?” said a voice not far from me.

I turned, and saw standing within two yards of me a woman about forty years of age, of decent appearance, though without either cap or bonnet.

“A Gypsy town, is it?” said I; “why, I thought it had been Kirk Yetholm.”

Woman. – “I canna say, sir; I dinna ken whether they have or not; I have been at Yetholm several years, about my ain wee bit o’ business, and never heard them utter a word that was not either English or broad Scotch. Some people say that they have a language of their ain, and others say that they have nane, and moreover that, though they call themselves Gypsies, they are far less Gypsy than Irish, a great deal of Irish being mixed in their veins with a very little of the much more respectable Gypsy blood. It may be sae, or it may be not; perhaps your honour will find out. That’s the woman, sir, just behind ye at the door. Gud e’en. I maun noo gang and boil my cup o’tay.”

To the woman at the door I now betook myself. She was seated on the threshold, and employed in knitting. She was dressed in white, and had a cap on her head, from which depended a couple of ribbons, one on each side. As I drew near she looked up. She had a full, round, smooth face, and her complexion was brown, or rather olive, a hue which contrasted with that of her eyes, which were blue.

“There is something Gypsy in that face,” said I to myself, as I looked at her; “but I don’t like those eyes.”

“A fine evening,” said I to her at last.

“Yes, sir,” said the woman, with very little of the Scotch accent; “it is a fine evening. Come to see the town?”

“Yes,” said I; “I am come to see the town. A nice little town it seems.”

“And I suppose come to see the Gypsies, too,” said the woman, with a half smile.

“Well,” said I, “to be frank with you, I came to see the Gypsies. You are not one, I suppose?”

“Indeed I am,” said the woman, rather sharply, “and who shall say that I am not, seeing that I am a relation of old Will Faa, the man whom the woman from Haddington was speaking to you about; for I heard her mention his name?”

“Then,” said I, “you must be related to her whom they call the Gypsy queen.”

“I am, indeed, sir. Would you wish to see her?”

“By all means,” said I. “I should wish very much to see the Gypsy queen.”

“Then I will show you to her, sir; many gentlefolks from England come to see the Gypsy queen of Yetholm. Follow me, sir!”

She got up, and, without laying down her knitting-work, went round the corner, and began to ascend the hill. She was strongly made, and was rather above the middle height. She conducted me to a small house, some little way up the hill. As we were going, I said to her, “As you are a Gypsy, I suppose you have no objection to a coro of koshto levinor?”

She stopped her knitting for a moment, and appeared to consider, and then resuming it, she said hesitatingly, “No, sir, no! None at all! That is, not exactly!”

“She is no true Gypsy, after all,” said I to myself.

We went through a little garden to the door of the house, which stood ajar. She pushed it open, and looked in; then, turning round, she said: “She is not here, sir; but she is close at hand. Wait here till I go and fetch her.” She went to a house a little farther up the hill, and I presently saw her returning with another female, of slighter build, lower in stature, and apparently much older. She came towards me with much smiling, smirking, and nodding, which I returned with as much smiling and nodding as if I had known her for threescore years. She motioned me with her hand to enter the house. I did so. The other woman returned down the hill, and the queen of the Gypsies entering, and shutting the door, confronted me on the floor, and said, in a rather musical, but slightly faltering voice:

“Now, sir, in what can I oblige you?”

Thereupon, letting the umbrella fall, which I invariably carry about with me in my journeyings, I flung my arms three times up into the air, and in an exceedingly disagreeable voice, owing to a cold which I had had for some time, and which I had caught amongst the lakes of Loughmaben, whilst hunting after Gypsies whom I could not find, I exclaimed:

“Sossi your nav? Pukker mande tute’s nav! Shan tu a mumpli-mushi, or a tatchi Romany?”

Which, interpreted into Gorgio, runs thus:

“What is your name? Tell me your name! Are you a mumping woman, or a true Gypsy?”

The woman appeared frightened, and for some time said nothing, but only stared at me. At length, recovering herself, she exclaimed, in an angry tone, “Why do you talk to me in that manner, and in that gibberish? I don’t understand a word of it.”

“Gibberish!” said I; “it is no gibberish; it is Zingarrijib, Romany rokrapen, real Gypsy of the old order.”

“Whatever it is,” said the woman, “it’s of no use speaking it to me. If you want to speak to me, you must speak English or Scotch.”

“Why, they told me as how you were a Gypsy,” said I.

“And they told you the truth,” said the woman; “I am a Gypsy, and a real one; I am not ashamed of my blood.”

“If yer were a Gyptian,” said I, “yer would be able to speak Gyptian; but yer can’t, not a word.”

“At any rate,” said the woman, “I can speak English, which is more than you can. Why, your way of speaking is that of the lowest vagrants of the roads.”

“Oh, I have two or three ways of speaking English,” said I; “and when I speaks to low wagram folks, I speaks in a low wagram manner.”

“Not very civil,” said the woman.

“A pretty Gypsy!” said I; “why, I’ll be bound you don’t know what a churi is!”

The woman gave me a sharp look; but made no reply.

“A pretty queen of the Gypsies!” said I; “why, she doesn’t know the meaning of churi!”

“Doesn’t she?” said the woman, evidently nettled; “doesn’t she?”

“Why, do you mean to say that you know the meaning of churi?”

“Why, of course I do,” said the woman.

“Hardly, my good lady,” said I; “hardly; a churi to you is merely a churi.”

“A churi is a knife,” said the woman, in a tone of defiance; “a churi is a knife.”

“Oh, it is,” said I; “and yet you tried to persuade me that you had no peculiar language of your own, and only knew English and Scotch: churi is a word of the language in which I spoke to you at first, Zingarrijib, or Gypsy language; and since you know that word, I make no doubt that you know others, and in fact can speak Gypsy. Come; let us have a little confidential discourse together.”

The woman stood for some time, as if in reflection, and at length said: “Sir, before having any particular discourse with you, I wish to put a few questions to you, in order to gather from your answers whether it is safe to talk to you on Gypsy matters. You pretend to understand the Gypsy language: if I find you do not, I will hold no further discourse with you; and the sooner you take yourself off the better. If I find you do, I will talk with you as long as you like. What do you call that?” – and she pointed to the fire.

“Speaking Gyptianly?” said I.

The woman nodded.

“Whoy, I calls that yog.”

“Hm,” said the woman: “and the dog out there?”

“Gyptian-loike?” said I.

“Yes.”

“Whoy, I calls that a juggal.”

“And the hat on your head?”

“Well, I have two words for that: a staury and a stadge.”

“Stadge,” said the woman, “we call it here. Now what’s a gun?”

“There is no Gypsy in England,” said I, “can tell you the word for a gun; at least the proper word, which is lost. They have a word – yag-engro – but that is a made-up word signifying a fire-thing.”

“Then you don’t know the word for a gun,” said the Gypsy.

“Oh dear me! Yes,” said I; “the genuine Gypsy word for a gun is puschca. But I did not pick up that word in England, but in Hungary, where the Gypsies retain their language better than in England: puschca is the proper word for a gun, and not yag-engro, which may mean a fire-shovel, tongs, poker, or anything connected with fire, quite as well as a gun.”

“Puschca is the word, sure enough,” said the Gypsy. “I thought I should have caught you there; and now I have but one more question to ask you, and when I have done so, you may as well go; for I am quite sure you cannot answer it. What is Nokkum?”

“Nokkum,” said I; “nokkum?”

“Aye,” said the Gypsy; “what is Nokkum? Our people here, besides their common name of Romany, have a private name for themselves, which is Nokkum or Nokkums. Why do the children of the Caungri Foros call themselves Nokkums?”

“Nokkum,” said I; “nokkum? The root of nokkum must be nok, which signifieth a nose.”

“A-h!” said the Gypsy, slowly drawing out the monosyllable, as if in astonishment.

“Yes,” said I; “the root of nokkum is assuredly nok, and I have no doubt that your people call themselves Nokkum because they are in the habit of nosing the Gorgios. Nokkums means Nosems.”

“Sit down, sir,” said the Gypsy, handing me a chair. “I am now ready to talk to you as much as you please about Nokkum words and matters, for I see there is no danger. But I tell you frankly that had I not found that you knew as much as, or a great deal more than, myself, not a hundred pounds, nor indeed all the money in Berwick, should have induced me to hold discourse with you about the words and matters of the Brown children of Kirk Yetholm.”

I sat down in the chair which she handed me; she sat down in another, and we were presently in deep discourse about matters Nokkum. We first began to talk about words, and I soon found that her knowledge of Romany was anything but extensive; far less so, indeed, than that of the commonest English Gypsy woman, for whenever I addressed her in regular Gypsy sentences, and not in poggado jib, or broken language, she would giggle and say I was too deep for her.

I should say that the sum total of her vocabulary barely amounted to three hundred words. Even of these there were several which were not pure Gypsy words – that is, belonging to the speech which the ancient Zingary brought with them to Britain. Some of her bastard Gypsy words belonged to the cant or allegorical jargon of thieves, who, in order to disguise their real meaning, call one thing by the name of another. For example, she called a shilling a ‘hog,’ a word belonging to the old English cant dialect, instead of calling it by the genuine Gypsy term tringurushi, the literal meaning of which is three groats. Then she called a donkey ‘asal,’ and a stone ‘cloch,’ which words are neither cant nor Gypsy, but Irish or Gaelic. I incurred her vehement indignation by saying they were Gaelic. She contradicted me flatly, and said that whatever else I might know I was quite wrong there; for that neither she nor any one of her people would condescend to speak anything so low as Gaelic, or indeed, if they possibly could avoid it, to have anything to do with the poverty-stricken creatures who used it.

It is a singular fact that, though principally owing to the magic writings of Walter Scott, the Highland Gael and Gaelic have obtained the highest reputation in every other part of the world, they are held in the Lowlands in very considerable contempt. There the Highlander, elsewhere “the bold Gael with sword and buckler,” is the type of poverty and wretchedness; and his language, elsewhere “the fine old Gaelic, the speech of Adam and Eve in Paradise,” is the designation of every unintelligible jargon. But not to digress.

On my expressing to the Gypsy queen my regret that she was unable to hold with me a regular conversation in Romany, she said that no one regretted it more than herself, but that there was no help for it; and that slight as I might consider her knowledge of Romany to be, it was far greater than that of any other Gypsy on the Border, or indeed in the whole of Scotland; and that as for the Nokkums, there was not one on the Green who was acquainted with half a dozen words of Romany, though the few words they had they prized high enough, and would rather part with their heart’s blood than communicate them to a stranger.

“Unless,” said I, “they found the stranger knew more than themselves.”

“That would make no difference with them,” said the queen, “though it has made a great deal of difference with me. They would merely turn up their noses, and say they had no Gaelic. You would not find them so communicative as me; the Nokkums, in general, are a dour set, sir.”

Before quitting the subject of language it is but right to say that though she did not know much Gypsy, and used cant and Gaelic terms, she possessed several words unknown to the English Romany, but which are of the true Gypsy order. Amongst them was the word tirrehi, or tirrehai, signifying shoes or boots, which I had heard in Spain and in the east of Europe. Another was calches, a Wallachian word signifying trousers. Moreover, she gave the right pronunciation to the word which denotes a man not of Gypsy blood, saying gajo, and not gorgio, as the English Gypsies do. After all, her knowledge of Gentle Romany was not altogether to be sneezed at.

Ceasing to talk to her about words, I began to question her about the Faas. She said that a great number of the Faas had come in the old time to Yetholm, and settled down there, and that her own forefathers had always been the principal people among them. I asked her if she remembered her grandfather, old Will Faa, and received for answer that she remembered him very well, and that I put her very much in mind of him, being a tall, lusty man, like himself, and having a skellying look with the left eye, just like him.

I asked her if she had not seen queer folks at Yetholm in her grandfather’s time. “Dosta dosta,” said she; “plenty, plenty of queer folk I saw at Yetholm in my grandfather’s time, and plenty I have seen since, and not the least queer is he who is now asking me questions.”

“Did you ever see Piper Allen?” said I; “he was a great friend of your grandfather’s.”

“I never saw him,” she replied; “but I have often heard of him. He married one of our people.”

“He did so,” said I, “and the marriage-feast was held on the Green just behind us. He got a good, clever wife, and she got a bad, rascally husband. One night, after taking an affectionate farewell of her, he left her on an expedition, with plenty of money in his pocket, which he had obtained from her, and which she had procured by her dexterity. After going about four miles he bethought himself that she had still some money, and returning crept up to the room in which she lay asleep, and stole her pocket, in which were eight guineas; then slunk away, and never returned, leaving her in poverty, from which she never recovered.”

I then mentioned Madge Gordon, at one time the Gypsy queen of the Border, who used, magnificently dressed, to ride about on a pony shod with silver, inquiring if she had ever seen her. She said she had frequently seen Madge Faa, for that was her name, and not Gordon; but that when she knew her, all her magnificence, beauty, and royalty had left her; for she was then a poor, poverty-stricken old woman, just able with a pipkin in her hand to totter to the well on the Green for water. Then with much nodding, winking, and skellying, I began to talk about Drabbing bawlor, dooking gryes, cauring, and hokking, and asked if them ‘ere things were ever done by the Nokkums: and received for answer that she believed such things were occasionally done, not by the Nokkums, but by other Gypsies, with whom her people had no connection.

Observing her eyeing me rather suspiciously, I changed the subject; asking her if she had travelled much about. She told me she had, and that she had visited most parts of Scotland, and seen a good bit of the northern part of England.

“Did you travel alone?” said I.

“No,” said she; “when I travelled in Scotland I was with some of my own people, and in England with the Lees and Bosvils.”

“Old acquaintances of mine,” said I; “why only the other day I was with them at Fairlop Fair, in the Wesh.”

“I frequently heard them talk of Epping Forest,” said the Gypsy; “a nice place, is it not?”

“The loveliest forest in the world!” said I. “Not equal to what it was, but still the loveliest forest in the world, and the pleasantest, especially in summer; for then it is thronged with grand company, and the nightingales, and cuckoos, and Romany chals and chies. As for Romany-chals there is not such a place for them in the whole world as the Forest. Them that wants to see Romany-chals should go to the Forest, especially to the Bald-faced Hind on the hill above Fairlop, on the day of Fairlop Fair. It is their trysting-place, as you would say, and there they musters from all parts of England, and there they whoops, dances, and plays; keeping some order nevertheless, because the Rye of all the Romans is in the house, seated behind the door:

Romany Chalor

Anglo the wuddur

Mistos are boshing;

Mande beshello

Innar the wuddur

Shooning the boshipen.”

Roman lads

Before the door

Bravely fiddle;

Here I sit

Within the door

And hear them fiddle.

“I wish I knew as much Romany as you, sir,” said the Gypsy. “Why, I never heard so much Romany before in all my life.”

She was rather a small woman, apparently between sixty and seventy, with intelligent and rather delicate features. Her complexion was darker than that of the other female; but she had the same kind of blue eyes. The room in which we were seated was rather long, and tolerably high. In the wall, on the side which fronted the windows which looked out upon the Green, were oblong holes for beds, like those seen in the sides of a cabin. There was nothing of squalor or poverty about the place.

Wishing to know her age, I inquired of her what it was. She looked angry, and said she did not know.

“Are you forty-nine?” said I, with a terrible voice, and a yet more terrible look.

“More,” said she, with a smile; “I am sixty-eight.”

There was something of the gentlewoman in her: on my offering her money she refused to take it, saying that she did not want it, and it was with the utmost difficulty that I persuaded her to accept a trifle, with which, she said, she would buy herself some tea.

But withal there was hukni in her, and by that she proved her Gypsy blood. I asked her if she would be at home on the following day, for in that case I would call and have some more talk with her, and received for answer that she would be at home and delighted to see me. On going, however, on the following day, which was Sunday, I found the garden-gate locked and the window-shutters up, plainly denoting that there was nobody at home.

Seeing some men lying on the hill, a little way above, who appeared to be observing me, I went up to them for the purpose of making inquiries. They were all young men, and decently though coarsely dressed. None wore the Scottish cap or bonnet, but all the hat of England. Their countenances were rather dark, but had nothing of the vivacious expression observable in the Gypsy face, but much of the dogged, sullen look which makes the countenances of the generality of the Irish who inhabit London and some other of the large English towns so disagreeable. They were lying on their bellies, occasionally kicking their heels into the air. I greeted them civilly, but received no salutation in return.

“Is So-and-so at home?” said I.

“No,” said one, who, though seemingly the eldest of the party, could not have been more than three-and-twenty years of age; “she is gone out.”

“Is she gone far?” said I.

“No,” said the speaker, kicking up his heels.

“Where is she gone to?”

“She’s gone to Cauldstrame.”

“How far is that?”

“Just thirteen miles.”

“Will she be at home to-day?”

“She may, or she may not.”

“Are you of her people?” said I.

“No-h,” said the fellow, slowly drawing out the word.

“Can you speak Irish?”

“No-h; I can’t speak Irish,” said the fellow, tossing up his nose, and then flinging up his heels.

“You know what arragod is?” said I.

“No-h!”

“But you know what ruppy is?” said I; and thereupon I winked and nodded.

“No-h;” and then up went the nose, and subsequently the heels.

“Good day,” said I; and turned away; I received no counter-salutation; but, as I went down the hill, there was none of the shouting and laughter which generally follow a discomfited party. They were a hard, sullen, cautious set, in whom a few drops of Gypsy blood were mixed with some Scottish and a much larger quantity of low Irish.

Between them and their queen a striking difference was observable. In her there was both fun and cordiality; in them not the slightest appearance of either. What was the cause of this disparity? The reason was they were neither the children nor the grandchildren of real Gypsies, but only the remote descendants, whereas she was the granddaughter of two genuine Gypsies, old Will Faa and his wife, whose daughter was her mother; so that she might be considered all but a thorough Gypsy; for being by her mother’s side a Gypsy, she was of course much more so than she would have been had she sprung from a Gypsy father and a Gentile mother; the qualities of a child, both mental and bodily, depending much less on the father than on the mother. Had her father been a Faa, instead of her mother, I should probably never have heard from her lips a single word of Romany, but found her as sullen and inductile as the Nokkums on the Green, whom it was of little more use questioning than so many stones.

Nevertheless, she had played me the hukni, and that was not very agreeable; so I determined to be even with her, and by some means or other to see her again. Hearing that on the next day, which was Monday, a great fair was to be held in the neighbourhood of Kelso, I determined to go thither, knowing that the likeliest place in all the world to find a Gypsy at is a fair; so I went to the grand cattle-fair of St. George, held near the ruined castle of Roxburgh, in a lovely meadow not far from the junction of the Teviot and Tweed; and there sure enough, on my third saunter up and down, I met my Gypsy.

We met in the most cordial manner – smirks and giggling on her side, smiles and nodding on mine. She was dressed respectably in black, and was holding the arm of a stout wench, dressed in garments of the same colour, who she said was her niece, and a rinkeni rakli. The girl whom she called rinkeni or handsome, but whom I did not consider handsome, had much of the appearance of one of those Irish girls, born in London, whom one so frequently sees carrying milk-pails about the streets of the metropolis.

By the bye, how is it that the children born in England of Irish parents account themselves Irish and not English, whilst the children born in Ireland of English parents call themselves not English but Irish? Is it because there is ten times more nationality in Irish blood than in English? After the smirks, smiles, and salutations were over, I inquired whether there were many Gypsies in the fair. “Plenty,” said she, “plenty Tates, Andersons, Reeds, and many others. That woman is an Anderson – yonder is a Tate,” said she, pointing to two common-looking females.

“Have they much Romany?” said I.

“No,” said she, “scarcely a word.”

“I think I shall go and speak to them,” said I.

“Don’t,” said she; “they would only be uncivil to you. Moreover, they have nothing of that kind – on the word of a rawnie they have not.”

I looked in her eyes; there was nothing of hukni in them, so I shook her by the hand; and through rain and mist, for the day was a wretched one, trudged away to Dryburgh to pay my respects at the tomb of Walter Scott, a man with whose principles I have no sympathy, but for whose genius I have always entertained the most intense admiration.

from ~ “Romano Lavo-Lil” by George Borrow