Romany or Gypsy Caravans

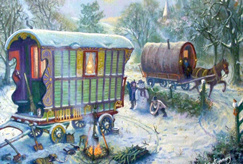

The sight of a Vardo or Romany caravan (often known to the non-travelling population as a ‘gypsy caravan’) is exciting for its rarity and conjures up an unhurried, picturesque pre-industrial lifestyle: images of Wind in the Willows, of a bow-topped roof with extravagantly carved and painted woodwork proceeding slowly behind a large and placid carthorse along narrow hedged lanes.

Referred to by travellers and gypsies as a ‘vardo’ or ‘wagon’, the horse-drawn caravan has been in use in the British Isles since the mid-nineteenth century. Initially made by the travellers themselves, the wagons began to be built by dedicated craftsmen around 1880, when the best examples began to be developed and their distinctive characteristics emerged. Fred Hill, Bill Wright and Duntons are some of the famous builders of the time. This particularly creative period lasted until the 1920s, but the wagons have continued to be made – though on a much more modest scale – until the present day.

There are five main types of vardo: The Brush, The Reading, the Ledge, The Bow Top and the straight-sided ‘Showman’s’ wagon; but within these categories no caravan is exactly the same. There are, however, typical characteristics – the pull-out bed, the child’s cupboard bed, plenty of cupboards and drawers; a little stove on the left-hand side; intricately carved and painted woodwork; pretty floral fabric lining the interior of the roof; and usually a window to the rear. The entrance was either ‘open-lot’ (open, but with curtains or canvas panels for protection) or fixed up with ‘stable’ doors with lace-clad windows.

The inhabitants took great pride in their caravans and enormous pains to decorate both inside and out as beautifully as possible. For the matriarch of the family, the caravan was both a status symbol and embodiment of domestic capability. The best china would be positioned so that it was visible from outside when the curtains were drawn aside or the doors flung open; copper pans would hang sparkling from pegs; lace, embroidery and fringing would embellish every surface and cushion; and the whole place would be spotlessly clean and tidy. Although small, a wagon would have been a permanent home to a travelling family. With plenty of imaginative storage, including a pan cupboard and a rack to the outside rear, life inside would have been perfectly manageable. The small stove heated up the space very effectively, so that the wagon provided a year-round living space. The wagons were light enough to be pulled easily by one dray horse.

On the road, the clip-clop of the horse’s hooves, the gentle sway of the wagon and the scent of fresh air through the front opening must have made it a wonderful form of travel. Many is the story where gypsies have been forced for one reason or another to abandon their wagons and live in ordinary houses, subsequently experiencing unhappiness – even depression, as well as bad cases of claustrophobia.

Horse-trading was an obvious vocation for gypsies, and the Appleby Horse Fair in Cumbria every summer was an essential destination. For many years, decorated wagons and brightly painted wares have made the event on Gallows Hill just outside Appleby one of the most colourful in the country. A place for gypsy families to catch up with each other’s news as well as for deals to be made and fun to be had, The Appleby Horse Fair is one of the largest and most important in romany fairs in Europe. In the 1960s, town councils began to ban fairs (failing in the case of Appleby) and make it very difficult to strike camp on roadsides. This kind of persecution, as well as the increase in motorised traffic, is one of the reasons why the gypsy caravan disappeared so quickly from view.

Nowadays, there is a revived interest in the authentic Vardo, partly for its antique value. Also, entrepreneurs are setting up horse-drawn holidays or letting out caravans to film or TV companies. And small businesses who deal in original and replica vardoes are doing a brisk trade.

From: Cottage Holiday Wales

Leave a Reply