Historical Gypsy

For Peace At Someone’s Death

For Gypsies there is far more concern for the living than for the dead. Yet the Rom believe there must always be a family vigil prior to the death of a family member. After the death there will be the funeral, which must be followed by a proper period of mourning.

English Gypsies believe that the owl is a harbinger of death. If they hear an owl hooting away in the distance, then it means someone close to them will die. If the owl is close by, with its cries loud and clear, then the person who will die is distant.

When an elderly member of the tribe is ill, and certain that he or she is going to die, work is sent out to all family members whereverthey happen to be scattered. They will immediatly return home, no matter from how far, for this is the one event that takes precedence over all others. The family members gather around the dying person’s bed, or outside around the tent or vardo.

There is always someone seated at the bedside until the death. It is a time for much socializing, with very little emotion shown regarding the dying man or woman.

Once dead, the person is caught between the world of the living and the world of the dead. He or she will stay there until buried. In order to ease the stay there, and to prepare them for the transition to the world of the dead, there is a simple ritual that is sometimes performed by the shuvani(often without the knowledge of any of the other members of the tribe).

A small fire is lit – quite separate from any cooking fire – as soon as possible after the last breath. The fire should be laid carefully so that it can be started with one light and so that it will burn for a sufficient time without having to have more fuel added. Onto the fire are thrown thyme, sage, and rosemary, in that order. The dead person’s name is chanted repeatedly as the shuvani walks backwards (widdershins, or counterclockwise) seven times around the fire, which is then left to burn itself out.

From Gypsy Love Magick

Art by Ann Falcone

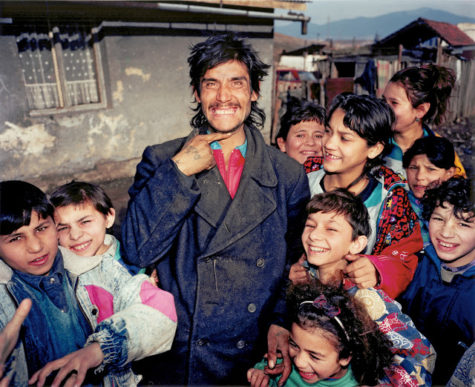

Romani Realities

It is easy to find images of the gypsy portrayed in vibrant colors, airy skirts and head scarves, but this is a personification of the abstract. This post serves as a grim reminder of what is all too often the harsh reality of Romani life in today’s world.

Approximately one million Roma lived in Europe before the second World War. The largest community which totaled about 300,000, was actually in Romania. This population was known for leading a nomadic life, and their employment included trading, wood and other crafting, merchants, laborers, and of course, musicians. Today, there are “officially” 620,000 Roma living in Romania; however, this is a controversial estimate, as leaders indicate their may be between 1 to 3 million in population. It is believed that the controversy in numbers exist from discrimination, as the gypsies often do not acknowledge their actual ethnicity.

The Roma have existed through a long and sometimes violent history which has kept this population as largely misunderstood. They have been characterized as social outcasts and through the existence of extreme poverty, they have been known as thieves and beggars. This has forced the majority of Roma Gypsies to live in very harsh conditions – has affected them mentally, spiritually, physically and economically – for generations. The reality for these folks today, particularly in northern Romania, is that they are living in make-shift houses constructed of old boards and plywood, and there are apparently political and cultural clashing and extenuating ramifications for which there has been no solution.

Romania is not the only country which hold disdain for this population, as the gypsy culture is steeped ‘twixt and ‘tween all of Europe, (Great Britain, Italy, Spain, France are currently “problem areas”), Russia and pretty much around the world.

According to Spain’s Guardia, no less than 95% of thievery crime is committed by gypsy children who are under 14 years of age, and due to this minor status, they are forced to release them back into the community, at large.

As depicted in the photos below, dailymail.uk gives the story of a mayor building a wall around an area where the gypsies live, along with many pictures of current living conditions in which the Roma exist today.

Craica has no sewerage, indoor water or power supplies, and ramshackle huts lie between heaps of rubbish. Some residents admit to drawing electricity cables from nearby blocks. Even so, there are many who want to stay and are resisting being moved.

‘I lived here for the last 20 years. My woman died here and I want to also die here,’ said 59-year-old Trandafir Varga, one of the oldest residents and a community leader, surrounded by younger Roma who nodded their head in approval.

‘There, we would be isolated. Here, we have horses, pigs,’ Varga said. ‘It’s like a concentration camp there at Cuprom, we aren’t going there. We want to stay outdoors and cannot stay in blocks.’

According to Catalin Chereches, this was part of a grand scheme to improve the lives of deeply impoverished families in the northern Romanian town who have been struggling to survive for generations.

About 980 Roma lived in Craica before the rehousing started in June. Some 100 families have so far been relocated to three administrative buildings of the former plant.

However, human rights groups claim that the 33-year-old Vienna-educated economist is racist. They have accused him of imprisoning the population in a ghetto and making their plight even worse.

‘This is completely wrong. We need to find solutions that integrate, not segregate,’ said Dezideriu Gergely of the European Roma Rights Centre. ‘There is a danger because dealing in such a manner with Roma issues only triggers the resentment and prejudices that already exist.’

Craica is a sharp contrast to the rest of the city, which has a well-preserved medieval center generously dotted with gothic churches, cafes and artisan shops.

Some Roma from Craica work as garbage collectors for the municipality and some at a furniture plant. Most are jobless, seasonal laborers or eke out a living from selling scrap metal.

Living conditions are so grim that many of those who have been moved say they are thankful to Mr Chereches, even though their new housing at the Cuprom offices leaves much to be desired, with only two bathrooms on each floor of several apartments.

‘I lived in a single room with six children and my wife at Craica,’ said 40-year-old Sandu, a seasonal construction worker rehoused to a small apartment with wooden furniture and an LCD television, bought with his own money. ‘My wife is jobless. I thank the mayor for giving me this place.’

Photographs shot in the heart of the slum – and at a dilapidated communist-era blocks where some of the families have been rehoused – show scenes of appalling poverty with families struggling to survive in temperatures which can plummet to -26C.

The concrete wall measures 1.8 metres high – built on an embankment, it appears much higher when you are inside the slum.

It is constructed on one side of a Roma neighborhood of crumbling apartment blocks, but because it links with other buildings and walls, it encloses the area with few access points. Mr Chereches says it was built to keep children safe from a main road.

He claims living conditions have improved by moving families away from a slum where naked children play in the dust with stray dogs and cats. But it still keeps Roma separate from other people and lacks space and bathrooms.

‘It’s clear, conditions there are not similar to the Hilton or Marriott. But this doesn’t mean this is not a step forward towards their civilization and emancipation,’ Mr Chereche explained in his tidy and modest office.

Faced with such conditions, it is hardly surprising that many Romanians say they would like to move to Britain in January 2014 when they gain the right to live and work unrestricted under European ‘freedom of movement’ rules.

Sources: Vermont Deadline and Daily Mail

The Gypsy Vardo

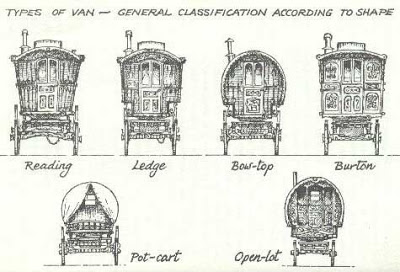

There are six design types. They are known by various names but are perhaps best called the Reading, the Ledge and the Bow-top. The Bow-top is the most typically Romani; the now extinct Brush – characteristic of brush, broom, rush and wickerwork makers; the Burton – most typically showman; and, the more modern one, the Open-lot.

Being individually built, no two wagons are exactly alike. They vary according to customer requirements, price, skill and location of builder and period. At the same time they have certain exterior features in common, and with few exceptions the interiors conform to a set plan or layout. Thus, the vardo is always one-roomed on four high wheels, with door and movable steps in front (the Brush wagon the only exception), sash windows, a rack called the ‘cratch’ and a pan-box at the rear.

Only minor variations in design occurred after about 1910, with the exception of the more modern Open-lot. Even the home-made vans – ‘peg-knife wagons’, supposedly shaped with the aid of that tool – tended to be along the same lines as the professionally built wagons. It was not uncommon for a traveler to add or remove features of an old wagon, re-mount a body on underworks other than its own, or replace unsound wheels by ones that differed in weight, size or structure from the original, thus altering the proportions.

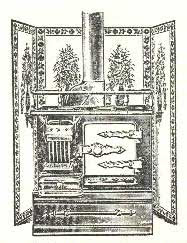

Inside the wagon the atmosphere is snug and homely, and the finer vans have an almost regal splendor. Almost everything one needs is to hand. Even in winter you need never be cold. The fire in the stove, if built up with windows closed for half an hour, will so heat the rails near the roof that they will be too hot to hold. One of the Coopers once claimed that he could bake a cake in his van by stoking up the fire, shutting the windows, and leaving the mixture in the tin on the table!

Inside the wagon the atmosphere is snug and homely, and the finer vans have an almost regal splendor. Almost everything one needs is to hand. Even in winter you need never be cold. The fire in the stove, if built up with windows closed for half an hour, will so heat the rails near the roof that they will be too hot to hold. One of the Coopers once claimed that he could bake a cake in his van by stoking up the fire, shutting the windows, and leaving the mixture in the tin on the table!

Inside the wagon the cabinet work may be either dark red polished mahogany or stained pine, and the walls are grained or scumbled in light-golden brown. In the vans that have had a lot of wear and tear the original wood finish has often been painted or grained over.

Internal layout, which varies little from type to type or van to van, has not changed for a century. The basic needs of the resident are the same and, in such confined space, there is only one sensible way to meet them. The entrance is frontal and half-doored. Through it, and on your immediate left, you find a tall, narrow wardrobe and beneath it perhaps a small brush cupboard.

The fireplace stands next, and is always on the left as you enter, for on that side the chimney pipe is in less danger from roadside trees. From a point about two feet above the top of the stove, the fireplace is boxed in to form an airing cupboard. On the front of this cupboard and above the fireplace is a brass-railed shelf and next comes the offside window, and beneath a locker seat for two.

The fireplace stands next, and is always on the left as you enter, for on that side the chimney pipe is in less danger from roadside trees. From a point about two feet above the top of the stove, the fireplace is boxed in to form an airing cupboard. On the front of this cupboard and above the fireplace is a brass-railed shelf and next comes the offside window, and beneath a locker seat for two.

To the right, as you enter, is a bow-fronted corner cupboard; the top part , usually having glass doors, is probably used for displaying china, and the cupboard below for boots and cleaning gear. Opposite the fire there is another locker seat, and of a cold winter’s day it is good to sit there, lean back and place your stockinged feet on the brass guard rail on the front of the stove. Next to the seat is a bow-fronted chest of drawers.

Filling in the back of the van is a two-berthed bed-place, the top bunk just below the rear window, and beneath it are two sliding doors. These in the daytime shut away a second, shorter bed-place in which the children sleep. Light is supplied from a bracket oil-lamp above the chest of drawers, the surface of which is used as a table. More light may come from candles.

©From The English Gypsy Caravan by C.H. Ward-Jackson and Denis E. Harvey 1973 Edition

Origin of the Name ‘Gypsy’

When the Roma arrived in Europe from the East, given their dark skin and eyes, they were believed to be from Turkey or Egypt. The word gypsy is derived from the word Egypt (gyp) and the people just called them gypsies. At that time the word did not have a negative connotation, but only identified the group as a people.

Also called travelers in many countries, they were nomadic people who rarely set down roots, traveling in wagons from place to place—always on the move—and sleeping in tents until the mid-1900s.

Gypsy Fortune Telling

Gypsy women, as long as we have known anything of Gypsy history, have been arrant fortune-tellers. They plied fortune-telling about France and Germany as early as 1414, the year when the dusky bands were first observed in Europe, and they have never relinquished the practice. There are two words for fortune-telling in Gypsy, bocht and dukkering. Bocht is a Persian word, a modification of, or connected with, the Sanscrit bagya, which signifies ‘fate.’ Dukkering is the modification of a Wallaco-Sclavonian word signifying something spiritual or ghostly. In Eastern European Gypsy, the Holy Ghost is called Swentuno Ducos.

Gypsy women, as long as we have known anything of Gypsy history, have been arrant fortune-tellers. They plied fortune-telling about France and Germany as early as 1414, the year when the dusky bands were first observed in Europe, and they have never relinquished the practice. There are two words for fortune-telling in Gypsy, bocht and dukkering. Bocht is a Persian word, a modification of, or connected with, the Sanscrit bagya, which signifies ‘fate.’ Dukkering is the modification of a Wallaco-Sclavonian word signifying something spiritual or ghostly. In Eastern European Gypsy, the Holy Ghost is called Swentuno Ducos.

Gypsy fortune-telling is much the same everywhere, much the same in Russia as it is in Spain and in England. Everywhere there are three styles – the lofty, the familiar, and the homely; and every Gypsy woman is mistress of all three and uses each according to the rank of the person whose vast she dukkers, whose hand she reads, and adapts the luck she promises.

There is a ballad of some antiquity in the Spanish language about the Buena Ventura, a few stanzas of which translated will convey a tolerable idea of the first of these styles to the reader, who will probably with no great reluctance dispense with any illustrations of the other two:

Late rather one morning

In summer’s sweet tide,

Goes forth to the Prado

Jacinta the bride:

There meets her a Gypsy

So fluent of talk,

And jauntily dressed,

On the principal walk.

“O welcome, thrice welcome,

Of beauty thou flower!

Believe me, believe me,

Thou com’st in good hour.”

Surprised was Jacinta;

She fain would have fled;

But the Gypsy to cheer her

“O cheek like the rose-leaf!

O lady high-born!

Turn thine eyes on thy servant,

But ah, not in scorn.

“O pride of the Prado!

O joy of our clime!

Thou twice shalt be married,

And happily each time.

“Of two noble sons Thou shalt be the glad mother,

One a Lord Judge,

A Field-Marshal the other.”

Gypsy females have told fortunes to higher people than the young Countess Jacinta: Modor – of the Gypsy quire of Moscow – told the fortune of Ekatarina, Empress of all the Russias. The writer does not know what the Ziganka told that exalted personage, but it appears that she gave perfect satisfaction to the Empress, who not only presented her with a diamond ring – a Russian diamond ring is not generally of much value – but also her hand to kiss.

The writer’s old friend, Pepíta, the Gitana of Madrid, told the bahi of Christina, the Regentess of Spain, in which she assured her that she would marry the son of the King of France, and received from the fair Italian a golden ounce, the most magnificent of coins, a guerdon which she richly merited, for she nearly hit the mark, for though Christina did not marry the son of the King of France, her second daughter was married to a son of the King of France, the Duke of M-, one of the three claimants of the crown of Spain, and the best of the lot; and Britannia, the Caumli, told the good luck to the Regent George on Newmarket Heath, and received ‘foive guineas’ and a hearty smack from him who eventually became George the Fourth – no bad fellow by the by, either as regent or king, though as much abused as Pontius Pilate, whom he much resembled in one point, unwillingness to take life – the sonkaypè or gold-gift being, no doubt, more acceptable than the choomapé or kiss-gift to the Beltenebrosa, who, if a certain song be true, had no respect for gorgios, however much she liked their money:

Britannia is my nav;

I am a Kaulo Camlo;

The gorgios pen I be

A bori chovahaunie;

And tatchipen they pens,

The dinneleskie gorgies,

For mande chovahans

The luvvu from their putsies.

Britannia is my name;

I am a swarthy Lovel;

The Gorgios say I be

A witch of wondrous power;

And faith they speak the truth,

The silly, foolish fellows,

For often I bewitch

The money from their pockets.

Fortune-telling in all countries where the Gypsies are found is frequently the prelude to a kind of trick called in all Gypsy dialects by something more or less resembling the Sanscrit kuhana; for instance, it is called in Spain jojana, hokano, and in English hukni. It is practised in various ways, all very similar; the defrauding of some simple person of money or property being the object in view. Females are generally the victims of the trick, especially those of the middle class, who are more accessible to the poor woman than those of the upper. One of the ways, perhaps the most artful, will be found described in another chapter (What is The Hukni? and What is Cauring?)

From: Romano Lavo-Lil

The Historical Gypsy

The first gypsies claimed to be the Christian nobility of Egypt, who had abandoned their possessions in order to retain their faith when the Muslims gained power. They were believed for a good period.

The first gypsies claimed to be the Christian nobility of Egypt, who had abandoned their possessions in order to retain their faith when the Muslims gained power. They were believed for a good period.

However, linguistic evidence strongly demonstrates that they actually originated in India, and moved west, migrating through the middle east into Europe. Although the Gypsies call themselves ‘Rom’ and their language is known as’Romani’, the Romani language has nothing in common with the language known as Romanian (which is a Romance language, derived from Latin and kin to French, Spanish, Italian, etc.). Romanibeen shown to be closely related to groups of languages and dialects (such as Hindi, Gujarati, Marathi and Cashmiri) still spoken in India and of the same origin as Sanskrit.

They were often described as dark-skinned magicians, entertainers, smiths, horsebreakers and other skilled tradeworkers. There is a good possibility that they originated belly dancing.

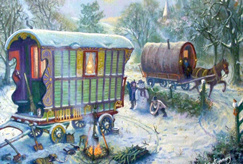

They lived in tents. Ggypsy wagons are a recent introduction. The wagons date from the late 18th early 19th century. Before that, they travelled by foot and horseback, setting up tents by night. The classic gypsy caravan wagons were usually built by commercial carriage shops for the gypsies, since they took a lot of woodworking and other equipment.

Reliable period info on gypsies is sadly lacking- the only people writing about them were the ones who wanted rid of them at all cost. I think it was in the fifteenth century that the pogroms against them really got rolling…Because gypsies have remained very secluded and secretive, cultural “tainting” has been comparatively low, and modern practices may well reflect medieval practices.

In France it was thought that these same people came from Bohemia and thus they were called ‘Bohemes’…. [thus began the English word “bohemian”]. There are Elizabethan laws against dressing or acting “as an Egyptian,” which from the descriptions seem to be what we would call ‘gypsies.’ It is quite possible that the word “gypsy” came into use as an abreviation of “Egyptian” somewhat later than the actual arrival of the Rom in England.

The Romnichels, or Rom’nies, began to come to the United States from England in 1850. Their arrival coincided with an increase in the demand for draft horses in agriculture and then in urban transportation. Many Romnichels worked as horse traders, both in the travel-intensive acquisition of stock and in long-term urban sales stable enterprise. After the rapid decline in the horse trade following the First World War, most Romnichels relied on previously secondary enterprises, “basket-making,” including the manufacture and sale of rustic furniture, and fortune telling.

The Rom arrived in the United States and Canada from Serbia, Russia and Austria-Hungary beginning in the 1880s, as part of the larger wave of immigration from southern and eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Primary immigration ended, for the most part, in 1914, with the beginning of the First World War and subsequent tightening of immigration restrictions. Many in this group specialized in coppersmith work, mainly the repair and refining of industrial equipment used in bakeries, laundries, confectioneries and other businesses. The Rom, too, developed the fortune-telling business in urban areas.

The Ludar, or “Rumanian Gypsies,” emigrated to North America during the great immigration from southern and eastern Europe between 1880 and 1914. Most of the Ludar came from northwestern Bosnia. Upon their arrival in North America they specialized as animal trainers and show people, and indeed passenger manifests show bears and monkeys as a major part of their baggage. Only a handful of items covering this group have been published, beginning in 1902. The ethnic language of the Ludar is a form of Romanian. They are occasionally referred to as Ursari in the literature.

Gypsies from Germany, generally referred to in the literature as Chikeners (Pennsylvania German, from German Zigeuner), sometimes refer to themselves as “Black Dutch.” (While the term “Black Dutch” has been adopted by these German Gypsies, it does not originate with this group and has been used ambiguously to refer to several non-Gypsy populations.) They are few in number and claim to have largely assimilated to Romnichel culture. In the past known as horse traders and basket makers, some continue to provide baskets to US Amish and Mennonite communities. The literature on this group is very sparse and unreliable.

The Hungarian (or Hungarian-Slovak) musicians also came to this country with the eastern European immigration. In the United States they continued as musicians to the Hungarian and Slovak immigrant settlements, and count the musical tradition as a basic cultural element.

The Irish Travelers immigrated, like the Romnichels, from the mid to late nineteenth century. The Irish Travelers specialized in the horse and mule trade, as well as in itinerant sales of goods and services; the latter gained in importance after the demise of the horse and mule trade. The literature also refers to this group as Irish Traders or, sometimes, Tinkers. Their ethnic language is referred to in the literature as Irish Traveler Cant.

The present population of Scottish Travelers in North America also dates from about 1850, although the 18th-century transportation records appear to refer to this group. Unlike that of the other groups, Scottish Traveler immigration has been continuous. Also unlike the other groups, Scottish Travelers have continued to travel between Scotland and North America, as well as between Canada and the United States, after immigration. Scottish Travelers also engaged in horse trading, but since the first quarter of the 20th century have specialized in itinerant sales and services.

Much of this information came from the Gypsy Lore Society.

Another Old Gypsy Trick

The Gypsy has some queer, old-fashioned gold piece; this she takes to some goldsmith’s shop, at the window of which she has observed a basin full of old gold coins, and shows it to the goldsmith, asking him if he will purchase it. He looks at it attentively, and sees that it is of very pure gold; whereupon he says that he has no particular objection to buy it; but that as it is very old it is not of much value, and that he has several like it.

“Have you indeed, Master?” says the Gypsy; “then pray show them to me, and I will buy them; for, to tell you the truth, I would rather buy than sell pieces like this, for I have a great respect for them, and know their value: give me back my coin, and I will compare any you have with it.”

The goldsmith gives her back her coin, takes his basin of gold from the window, and places it on the counter. The Gypsy puts down her head, and pries into the basin. “Ah, I see nothing here like my coin,” says she. “Now, Master, to oblige me, take out a handful of the coins and lay them on the counter; I am a poor, honest woman, Master, and do not wish to put my hand into your basin. Oh! if I could find one coin like my own, I would give much money for it; barributer than it is worth.”

The goldsmith, to oblige the poor, simple, foreign creature (for such he believes her to be), and, with a considerable hope of profit, takes a handful of coins from the basin and puts them upon the counter.

“I fear there is none here like mine, Master,” says the Gypsy, moving the coins rapidly with the tips of her fingers. “No, no, there is not one here like mine – kek yeck, kek yeck – not one, not one. Stay, stay! What’s this, what’s this? So se cavo, so se cavo? Oh, here is one like mine; or if not quite like, like enough to suit me. Now, Master, what will you take for this coin?”

The goldsmith looks at it, and names a price considerably above the value; whereupon she says: “Now, Master, I will deal fairly with you: you have not asked me the full value of the coin by three three-groats, three-groats, three-groats; by trin tringurushis, tringurushis, tringurushis. So here’s the money you asked, Master, and three three-groats, three shillings, besides. God bless you, Master! You would have cheated yourself, but the poor woman would not let you; for though she is poor she is honest”: and thus she takes her leave, leaving the goldsmith very well satisfied with his customer – with little reason, however, for out of about twenty coins which he laid on the counter she had filched at least three, which her brown nimble fingers, though they seemingly scarcely touched the gold, contrived to convey up her sleeves.

This kind of pilfering is called by the English Gypsies cauring, and by the Spanish ustilar pastesas, or stealing with the fingers. The word caur seems to be connected with the English cower, and the Hebrew kãra, a word of frequent occurrence in the historical part of the Old Testament, and signifying to bend, stoop down, incurvare.

From: Romano Lavo-Lil

An Old Gypsy Trick

The Gypsy makes some poor simpleton of a lady believe that if the latter puts her gold into her hands, and she makes it up into a parcel, and puts it between the lady’s feather-bed and mattress, it will at the end of a month be multiplied a hundredfold, provided the lady does not look at it during all that time. On receiving the money she makes it up into a brown paper parcel, which she seals with wax, turns herself repeatedly round, squints, and spits, and then puts between the feather-bed and mattress – not the parcel of gold, but one exactly like it, which she has prepared beforehand, containing old halfpence, farthings, and the like; then, after cautioning the lady by no means to undo the parcel before the stated time, she takes her departure singing to herself:

O dear me! O dear me!

What dinnelies these gorgies be.

The above artifice is called by the English Gypsies the hukni, and by the Spanish hokhano baro, or the great lie. Hukni and hokano were originally one and the same word; the root seems to be the Sanscrit huhanã, lie, trick, deceit.

From: Romano Lavo-Lil

The Gypsy Horse

The horses were an integral part of life; they pulled the colorful wagons that were what these people called home. Often cared for by the children, it was essential that the horses be kind and quiet, with a willing disposition. They also had to be hardy, sound and easily kept due to the nature of their lives.

Easy to recognize, these magical horses come in nearly all colors. They have amazing amounts of hair. Manes that grow below the shoulder, tails that drag on the ground and feet that appear to be floating is only the beginning.

The Gypsy Horse, or Gypsy Vanner / Gypsy Cob as it is also referred, is truly a breed for all! This horse has the spirit to excel at all disciplines. There is a wide range in size and the average gypsy stands between 14 and 16.2 hands, which makes it a great prospect for adults or children alike. Its natural disposition allows it to be perfectly suited for new horse people or individuals who just desire an easy going partner. It’s abundance of mane, tail and feather set it apart from all other breeds

The beauty of this horse is surpassed only by their gentle and intelligent nature, making them highly sought after, even outside the Romany culture.

Gypsy Funeral

At one time, it was commonly believed that just as the body is a vehicle for the spirit on earth, the vardo is the vehicle for the body on earth. When someone died, their vardo and most of their possessions were burned because their “vehicle for the body” was no longer needed.

Funerals are a very important rite of passage for the Gypsy Traveler community. When a Gypsy dies it is usual for a vigil to be kept over the body, which is kept illuminated until after the time of the funeral. The deceased is usually buried with the owner’s intimate personal possessions such as jewelry and trinkets.

Some Gypsy funerals will attract people from all over the country to pay their respects and floral tributes are usually on a grand scale. Personal items belonging to the deceased such as clothing, bedding and china are usually burnt or destroyed after the funeral. Many years ago, the wagon was very often burnt as well, but this is rarely done today.