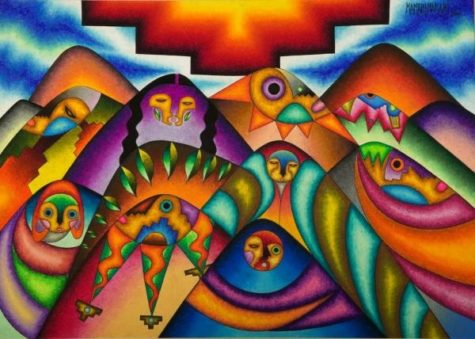

Inca Gods and Spirits

In Inca mythology, Apu was the name given to powerful mountain spirits. The Incas also used Apu to refer to the sacred mountains themselves; each mountain had its own spirit, with the spirit going by the name of its mountain domain. An Apu is simultaneously:

- The sacred spirit of a mountain

- The mountain itself

- The spirit who lives atop the mountain.

Paradoxically, the Apu is inseparable from the mountain even though the spirit itself is completely mobile and perfectly capable of traveling far.

Apu literally means “lord.” Female Apus are address as “mama.” Apus were typically male spirits, although some female examples do exist. Female Apus include Mama Simona of Cuzco; Mama Patukusi of Machu Pichu; and Mama Veronica near Cuzco. Her Quechua name is Wakay Willca.

Every mountain peak in the Andes has its own Apu, but the most famous are the twelve associated with Cuzco:

- Apu Ausangate

- Apu Salkanaty

- Mama Simona

- Apu Pikol

- Apu Manuel Pinta

- Apu Wanakauri

- Apu Pachatusan

- Apu Pijchu

- Apu Saqsaywaman

- Apu Wiraqochan

- Apu Pukin

- Apu Senq’a

In the Quechua language—spoken by the Incas and now the second most common language in modern Peru—the plural of Apu is Apukuna.

Manifestation:

Apus frequently take the form of mischievous, playful, but helpful children. For instance, Apu Ausangate, considered the most powerful Apu of Cuzco, manifests as a blond, fair-skinned child wearing white clothes and riding a white horse. Don’t let their chosen form fool you ~ they are ancient and powerful spirits.

Gifts:

Small stones resembling animals or plants are sacred gifts from the Apus and may be used to bring whatever the stone resembles into your life. The resemblance may be enhanced by carving. These gifts are not limited to one person. They may be given to others or passed down through generations of a family. They may also be purchased at Andean pilgrimage sites. Modern versions of these amulets include miniature trucks, tools, and even passports.

Ritual and Offerings:

Travel to the Andes and visit the mountains to request their blessings and protection. Offerings include the following:

- Coca leaves

- Libations of water and alcoholic beverages

One of the most basic concepts of life in the high Andes communities is that of Ayni, or reciprocity, which connotes an ever-shifting, dynamic balance in relationship. This give and take informs not only connections that exist among people, but also the bonds between humans and the natural world, and most especially those between the people and the Apu.

The k’intu offering that reinforces this relationship has the Coca leaf as its main ingredient. Spiritual elders of the villages, or Misayoqs, say that the coca leaf is the favorite food of the Apus.

Three perfect coca leaves are infused with the breath of the Misayoq. This places his intention for the well being of the people into the offering. The k’intu is offered as a sacrament, to ensure his benevolent protection towards the people who dwell in his mighty presence.

An interesting account of an experience of talking with the Apu can be found here. It looks like they also offer trips to Peru, in case you are interested.

About The Inca Mountain Spirits

Inca mythology worked within three realms: Hanan Pacha (the upper realm), Kay Pacha (the human realm), and Uku Pacha (the inner world, or underworld). Mountains—rising up from the human world toward Hanan Pacha—offered the Incas a connection with their most powerful gods in the heavens.

The Apu mountain spirits also served as protectors, watching over their surrounding territories and protecting nearby Inca inhabitants as well as their livestock and crops. In times of trouble, the Apus were appeased or called upon through offerings. It’s believed they predated people in the Andes regions and that they are constant guardians of those who inhabit this area.

Small offerings such as chicha (corn beer) and coca leaves were common. In desperate times, the Incas would resort to human sacrifice.

Juanita—the “Inca Ice Maiden” discovered atop Mount Ampato in 1995 (now on display in the Museo Santuarios Andinos in Arequipa)—may well have been a sacrifice offered to the Ampato mountain spirit between 1450 and 1480.

The Apus in Modern Peru

The Apu mountain spirits did not fade away following the demise of the Inca Empire.

In fact, they are very much alive in modern Peruvian folklore. Many present-day Peruvians, especially those born and raised within traditional Andean communities, still hold beliefs that date back to the Incas (albeit these beliefs are often combined with aspects of Christian faiths, most frequently the Catholic faith).

The notion of the Apu spirits remains common in the highlands, where some Peruvians still make offerings to the mountain gods. According to Paul R. Steele in Handbook of Inca Mythology, “Trained diviners can communicate with the Apus by tossing handfuls of coca leaves onto a woven cloth and studying messages encoded in the configurations of leaves.”

Understandably, the highest mountains in Peru are often the most sacred. Smaller peaks, however, are also venerated as Apus. Cuzco, the former Inca capital, has twelve sacred Apus, including the towering 20,945-foot Ausangate, Sacsayhuamán and Salkantay. Machu Picchu—the “Old Peak,” after which the archeological site is named—is also a sacred Apu, as is the neighboring Huayna Picchu.

Alternative Meanings of Apu

Apu can also be used to describe a great lord or another authority figure. The Incas gave the title Apu to each governor of the four suyus (administrative regions) of the Inca Empire.

In Quechua, Apu has a variety of meanings beyond its spiritual significance, including rich, mighty, boss, chief, powerful, and wealthy.

Sources:

- Encyclopedia of Spirits

- Wayra Peru Travel

- Trip Savvy