Grain

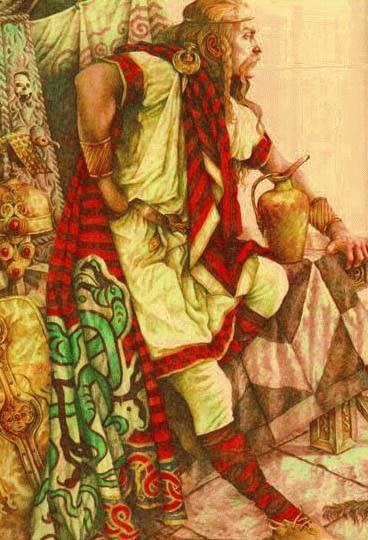

Lugh (pronounced LOO) was known to the Celts as a god of craftsmanship and skill — in fact, he was known as the Many-Skilled God, because he was good at so many different things. In one legend, Lugh arrives at Tara, and is denied entrance. He enumerates all the great things he can do, and each time the guard says, “Sorry, we’ve already got someone here who can do that.” Finally Lugh asks, “Ah, but do you have anyone here who can do them ALL?”

- Origin: Celtic

- Attributes: Magical spear, harp

- Bird: Raven

- Animal: Lion, horse

- Planet: Sun

- Plant: Red corn cockles

Lugh, Lord of Craftsmanship, Light, Victory and War, is a master builder, harpist, poet, warrior, sorcerer, metalworker, cupbearer and physician. It’s hard to envision anything at which Lugh does not excel.

- Also known as:

Lug, Luc, Lugos, Lleu Llaw Gyffes, Bright One of the Skillful Hand - Favored people:

Artisans, crafts people, poets, artists, physicians, soldiers, and warriors. - Manifestation:

Shining, handsome, charming and witty. He has a silver tongue to match his skillful hands. - Consorts:

Lugh has different consorts in different locations but he was frequently linked to Rosemerta. - Spirit Allies:

Lugh shared the city of Lyon with Kybele and Paris with Isis. In battle, Lugh used his own weapons but also those belonging to Manannan.

Lugh was venerated throughout the ancient Celtic world. Modern scholars perceive him as especially significant because his veneration indicates the existence of pan-Celtic spiritual traditions. (Celts once ruled a huge swathe of continental Europe before being forced to the very edges of the continent.)

At least fourteen European cities are named for Lugh including Laon, Leyden, Loudon and Lyon. Lyon’s old name was Lugduhum, meaning “Lugh’s Fort.” Tat city is believed to have been his cult center. Its coins bore the images of ravens which may be a reference to Lugh. Carlisle in England, the former Lugubalium, is also named in Lugh’s honor. Some theorize that Lugh’s name is reflected in an older name for paris: Lutetia.

The Romans identified Lugh with Mercury. Many European churches dedicated to Michael the Archangel are believed to have been built over sites once dedicated to Lugh. Post-Christianity many of Lugh’s sacred functions were reassigned to saints like Patrick and Luke.

Lugh apparently traveled westward through Europe. Irish and Welsh myths describe his first appearance in their pantheon. He is greeted with resistance from women in Wales. His first public act in Ireland is to join battle with the Tuatha De Danaan (his father’s people) against the Fomorian, his mother’s people. Lugh chooses allegiance with the paternal line; the myth may be interpreted as indicating the beginnings of patriarchy in Ireland.

- Feast: August 1st

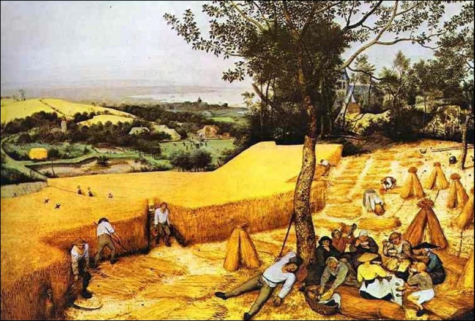

August 1st is the festival of Lughnasadh. Lughnasadh (sometimes spelled Lughnasa) means “the marriage of Lugh.” Lugh the sun and the Earth Mother renew their wedding vows annually during the full moon in August and invite all to gather and revel with them. Lughnasadh celebrates the consummation of their sacred relationship.

Once upon a time, Lughnasadh was a four week festival.: the last two weeks of July and the first two weeks of August, roughly corresponding to when the sun is in Leo, the astrological sign that belongs to the sun and epitomizes its power. In modern Irish Gaelic, the month of August is Lunasa. However the modern Wiccan sabbat of Lughnasadh is almost always devoted solely to the eve of July 31 leading into Lughnasadh Day on August 1st.

Celebrating Lugh Today:

Lughnasadh is a pagan holiday is dedicated to this capable God, and is celebrated every year on August 1st.

Take the opportunity this day to celebrate your own skills and abilities, and make an offering to Lugh to honor him, the god of craftsmanship.

Here’s How:

Before you begin, take a personal inventory. What are your strong points? Everyone has a talent — some have many, some have one that they’re really good at. Are you a poet or writer? Do you sing? How about needlecraft, woodworking, or beading? Can you tap dance? Do you cook? How about painting? Think about all the things you can do — and all of the things you’d like to learn to do, and the things you’d like to get better at. Once you sit down and think about it, you might be surprised to realize how accomplished you really are.

Decorate your altar with items related to your skill or talent. If your skill relates to something tangible, like sewing or jewelry-making, put some of your craft supplies on the altar. If it’s an ability to DO, rather than MAKE, such as dancing or singing, put some symbol of your ability on your altar. Do you have a favorite outfit you wear when you dance? A particular song lyric that you know you’re fabulous with? Add as many items as you like to your altar.

You’ll need a candle to symbolize Lugh, the god. Any harvest color is good, because he came up with the idea of a grain festival to honor his foster mother, Tailtiu. Place the candle on your altar in the center. Feel free to add some stalks of grain if you like — you can combine this rite with one honoring the harvest, if you choose.

Light the candle, and take a moment to think about all the things you are good at. What are they? Are you proud of your accomplishments? Now’s your chance to boast a little, and take some pride in what you’ve learned to do.

Announce your own talents in the following incantation. Say:

Mighty Lugh, the many-skilled god,

he who is a patron of the arts,

a master of trades, and a silver-tongued bard.

Today I honor you, for I am skilled as well.

I am deft with a needle,

strong of voice,

and paint beauty with my brush strokes.*

*Obviously, you would insert your pride in your own skills here.

Now, consider what you wish to improve upon. Is your tennis-playing out of whack? Do you feel inadequate at bungee jumping, yodeling, or drawing?

Now’s the time to ask Lugh for his blessing. Say:

Lugh, many-skilled one,

I ask you to shine upon me.

Share your gifts with me,

and make me strong in skill.

At this time, you should make an offering of some sort. The ancients made offerings in exchange for the blessings of their gods — quite simply, petitioning a god was a reciprocal act, a system of exchange. Your offering can a tangible one: grain, fruit, wine, or even a sample of your own talents and skills — imagine dedicating a song or painting to Lugh. It can also be an offering of time or loyalty. Whatever it is, it should come from the heart.

Say:

I thank you, mighty Lugh, for hearing my words tonight.

I thank you for blessing me with the skills I have.

I make this offering of (whatever it is you are offering) to you

as a small token of honor.

Take a few more moments and reflect on your own abilities. Do you have faith in your skills, or do you deflect compliments from others? Are you insecure about your abilities, or do you feel a surge of pride when you sew/dance/sing/hula hoop? Meditate on your offering to Lugh for a few moments, and when you are ready, end the ritual.

Tips:

If you are performing this rite as part of a group, family or coven setting, go around in a circle and have each person take their turn to express their pride in their work, and to make their offerings to Lugh.

Sources: Encyclopedia of Spirits and PaganWiccan

When Lammastide rolls around, the fields are full and fertile. Crops are abundant, and the late summer harvest is ripe for the picking. This is the time when the first grains are threshed, apples are plump in the trees, and gardens are overflowing with summer bounty. In nearly every ancient culture, this was a time of celebration of the agricultural significance of the season. Because of this, it was also a time when many gods and goddesses were honored. These are some of the many deities who are connected with this earliest harvest holiday.

Adonis (Assyrian): Adonis is a complicated god who touched many cultures. Although he’s often portrayed as Greek, his origins are in early Assyrian religion. Adonis was a god of the dying summer vegetation. In many stories, he dies and is later reborn, much like Attis and Tammuz.

Attis (Phrygean): This lover of Cybele went mad and castrated himself, but still managed to get turned into a pine tree at the moment of his death. In some stories, Attis was in love with a Naiad, and jealous Cybele killed a tree (and subsequently the Naiad who dwelled within it), causing Attis to castrate himself in despair. Regardless, his stories often deal with the theme of rebirth and regeneration.

Ceres (Roman): Ever wonder why crunched-up grain is called cereal? It’s named for Ceres, the Roman goddess of the harvest and grain. Not only that, she was the one who taught lowly mankind how to preserve and prepare corn and grain once it was ready for threshing. In many areas, she was a mother-type goddess who was responsible for agricultural fertility.

Dagon (Semitic): Worshiped by an early Semitic tribe called the Amorites, Dagon was a god of fertility and agriculture. He’s also mentioned as a father-deity type in early Sumerian texts and sometimes appears as a fish god. Dagon is credited with giving the Amorites the knowledge to build the plough.

Demeter (Greek): The Greek equivalent of Ceres, Demeter is often linked to the changing of the seasons. She is often connected to the image of the Dark Mother in late fall and early winter. When her daughter Persephone was abducted by Hades, Demeter’s grief caused the earth to die for six months, until Persephone’s return.

Lugh (Celtic): Lugh was known as a god of both skill and the distribution of talent. He is sometimes associated with midsummer because of his role as a harvest god, and during the summer solstice the crops are flourishing, waiting to be plucked from the ground at Lughnasadh.

Mercury (Roman): Fleet of foot, Mercury was a messenger of the gods. In particular, he was a god of commerce and is associated with the grain trade. In late summer and early fall, he ran from place to place to let everyone know it was time to bring in the harvest. In Gaul, he was considered a god not only of agricultural abundance but also of commercial success.

Neper (Egyptian): This androgynous grain deity became popular in Egypt during times of starvation. He later was seen as an aspect of Osiris, and part of the cycle of life, death and rebirth.

Parvati (Hindu): Parvati was a consort of the god Shiva, and although she does not appear in Vedic literature, she is celebrated today as a goddess of the harvest and protector of women in the annual Gauri Festival.

Pomona (Roman): This apple goddess is the keeper of orchards and fruit trees. Unlike many other agricultural deities, Pomona is not associated with the harvest itself, but with the flourishing of fruit trees. She is usually portrayed bearing a cornucopia or a tray of blossoming fruit.

Tammuz (Sumerian): This Sumerian god of vegetation and crops is often associated with the cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

When Babylon became the capital of Mesopotamia, Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon was elevated to the level of supreme god. Acknowledged as the creator of the universe and of humankind, the god of light and life, and the ruler of destinies, he rose to such eminence that he claimed 50 titles. His name literally means “bull calf of the sun”.

In order to explain how Marduk seized power, the Enûma Elish was written, which tells the story of Marduk’s birth, heroic deeds and becoming the ruler of the gods. Also included in this document are the fifty names of Marduk.

According to this ancient epic poem of creation, Marduk defeated Tiamat and Kingu, the dragons of chaos, and thereby gained supreme power.

The story is as follows:

A civil war between the gods was growing to a climactic battle. The call went out to find one god who could defeat the opposing Gods and the Dragons of Chaos rising against them. Marduk, a very young god, answered the call and was promised the position of head god if he could get the job done.

To prepare for battle, he makes a bow, fletches arrows, grabs a mace, throws lightning before him, fills his body with flame, makes a net to encircle Tiamat (the dragon) within it, gathers the four winds so that no part of her could escape, creates seven nasty new winds such as the whirlwind and tornado, and raises up his mightiest weapon, the rain-flood. Then he sets out for battle, mounting his storm-chariot drawn by four horses with poison in their mouths. In his lips he holds a spell and in one hand he grasps a herb to counter poison.

First, he challenges the leader of the Anunnaki gods, the dragon of the primordial sea Tiamat, to single combat and defeats her by trapping her with his net, blowing her up with his winds, and piercing her belly with an arrow.

Then, he proceeds to defeat Kingu, the god in charge of the army and who also wore the Tablets of Destiny on his breast. Marduk “wrested from him the Tablets of Destiny, wrongfully his” and assumed his new position. Under his reign humans were created to bear the burdens of life so the gods could be at leisure.

Marduk was depicted as a human, often with his symbol the snake-dragon which he had taken over from the god Tishpak. Another symbol that stood for Marduk was the spade.

Another take on the story:

In ancient Mesopotamia, the final days of the year were a time of decay and death, as the very year itself withered and died, and thoughts turned to the departed. The terrible chaos goddess Tiamat threatened to destroy the world and all its inhabitants; she was a sea-monster, born of the marriage of fresh and salt water, who gave birth to a generation of young gods, on whom she later declared war. From these young gods, one rose to lead the fight against Tiamat and defeated her, thus saving the world.

Marduk’s Names:

He was Marduk, a young Sun god, whose name comes through amar-ud – ‘Youth of the Sun’, and maru Duku – ‘Child of the Holy chamber’, who was also called Bêl which means ‘Lord’ and may be known to Bible readers as Ba’al (when Bêl is mentioned, it always refers to Marduk). He rose to such eminence that he claimed 50 titles. His name literally means “bull calf of the sun”.

The Fifty Names of Marduk as recounted in the Enûma Elish, and can be found here: The Fifty Names of Marduk.

Attributes and Powers:

Marduk fought against chaos and was killed, spending time in the underworld before being resurrected, returning to life to defeat the forces of evil and so becoming the King of the gods.

He was a fertility god and a grain god, his death symbolized the death of the sun in winter, his sojourn in the underworld is the grain lying dormant in the ground, and his return is the arrival of spring, new growth and green leaves.

Marduk was depicted as a human, often with his symbol the snake-dragon which he had taken over from the god Tishpak. Another symbol that stood for Marduk was the spade.

According to the mythology of the Necromonicon, (a work of fiction by H P Lovecraft), and an adaptation of that mythology, The Necronomicon Spellbook, Marduk was the God who defeated the Ancient Ones long before the creation of matter as we know it. The Fifty Names, (according to the Necronomicon) were titles given to Marduk by the Elder Gods after he had helped them to defeat the Ancient Ones. These names were assigned Sigils and Words of Power, you can read more about them here: About The Fifty Names of Marduk