Hag

- Titles: Goddess of Abundance, Queen of Witches

- Also known as: Bertha; Perchta; Frau Berta; Eisen Berta, Berchtli

- Origin: Germanic

- Sacred plants: Holly, mayflower

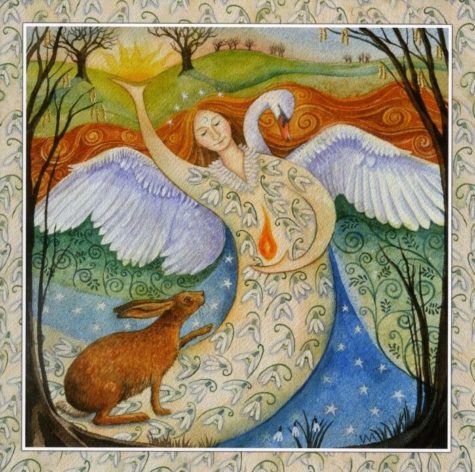

- Sacred creatures: Crickets, swans, geese.

Bavaria is the ancient stronghold of Berchta, goddess of abundance. Allegedly whatever you give her will be returned many times over. Berchta rules a sort of transit area for souls, caring for and guarding those who died as babies. Depending on the version, they either stay in her garden forever or she tends them until they reincarnate and receive new life. She protects living children, too. German folk tales describe a beautiful lady dressed in white who mysteriously appears in the middle of the night to nurse babies.

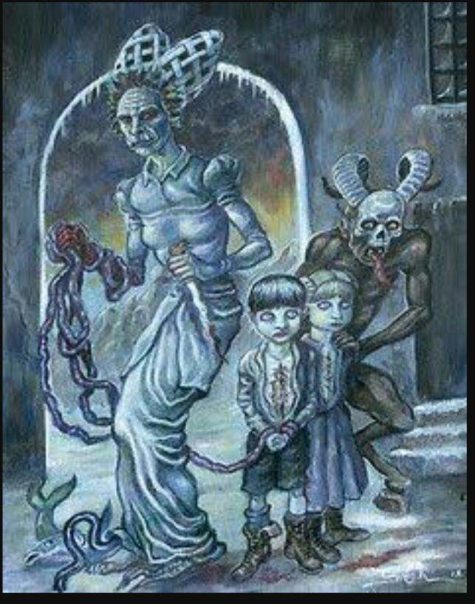

Initially, Perchta was the upholder of cultural taboos, such as the prohibition against spinning on holidays. She was an immensely popular goddess, and so post-Christianity she was aggressively demonized by the Church as a Queen of Witches. People were told to baptize their babies because otherwise they’d end up in Berchta’s realm, not in Heaven. She is among the leaders of the Wild Hunt, usually leading a parade of unbaptized babies.

She evolved into a bogeywoman still invoked as a threat to make children behave before Yule. She allegedly punishes “bad children” but gives gifts to good ones.

This old story is as follows:

In the folklore of Bavaria and Austria, Perchta was said to roam the countryside at midwinter, and to enter homes during the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany (especially on the Twelfth Night). She would know whether the children and young servants of the household had behaved well and worked hard all year. If they had, they might find a small silver coin next day, in a shoe or pail. If they had not, she would slit their bellies open, remove stomach and guts, and stuff the hole with straw and pebbles.

She was particularly concerned to see that girls had spun the whole of their allotted portion of flax or wool during the year. She would also slit people’s bellies open and stuff them with straw if they ate something on the night of her feast day other than the traditional meal of fish and gruel.

Berchta protects:

- Unbaptized babies

- Stillbirths, miscarriages, abortions

- Those driven to suicide by broken hearts or despair

- Dead souls who lack people to remember them

- Dead souls who have not received proper, respectful burial

The types of dead souls Berchta protects have a tendency to trouble the living by manifesting as destructive ghosts. Should you be afflicted by such a ghost, petition Berchta to soothe and remove it, escorting it to her realm, where it will be much happier.

- Manifestations

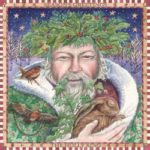

A beautiful woman with pearls braided into her gold hair. A white veil obscures her face, and she wears a long, white silk dress. She has another look too: an old decrepit hag with long, wild grey hair and disheveled clothes.

In many old descriptions, Bertha had one large foot, sometimes called a goose foot or swan foot. Grimm thought the strange foot symbolized her being a higher being who could shapeshift to animal form. He noticed that Bertha with a strange foot exists in many languages:

“It is apparently a swan maiden’s foot, which as a mark of her higher nature she cannot lay aside…and at the same time the spinning-woman’s splayfoot that worked the treadle”.

Because she sometimes manifests with one webbed goose foot, it is possible that Berchta may be the original Mother Goose. In the Tyrol she appears as little old woman with a very wrinkled face, bright lively eyes, and a long hooked nose; her hair is disheveled, her garments tattered and torn.

- Attributes

When she’s young and beautiful, she carries the keys to happiness in one hand and a spray of mayflowers in the other; as a hag, she carries a distaff.

- Realm

A subterranean palace with a fabulous garden where she welcomes souls of children who died in infancy.

She maintains other homes within hollow mountains.

- Spirit allies

Perchta travels with a retinue of spirits called Perchten. Christian legend says the devil rides in their midst, but this may indicate the presence of a male deity who accompanies her.

- Sacred time

Berchta is celebrated throughout the entire Yule season. Post-Christianity, Yule became synonymous with Christmas, but in its original Pagan context it was a lengthier season.

In German tradition, the Feast of the Epiphany (Jan 6) is Berchtentag – Berchta’s Day. The preceding eve is Berchtennacht. The festival is celebrated with processions characterized by grotesque masks.

- Sacred places

Berchtesgaden in the Austrian Alps means “Berchta’s Garden.” Many springs near Salzburg are named in her honor.

- Offerings

Leave offerings out for her on Epiphany Eve, the way offerings are left for Santa. Not milk and cookies, though. Berchta likes a hearty meal: herring and dumplings is her favorite. Give her schnapps or other alcoholic beverages.

A Goddess of Many Names

Perchta had many different names depending on the era and region: Grimm listed the names Perahta and Berchte as the main names, followed by Berchta in Old High German, as well as Behrta and Frau Perchta. In Baden, Swabia, Switzerland and Slovenian regions, she was often called Frau Faste (the lady of the Ember days) or Pehta or ‘Kvaternica’, in Slovene. Elsewhere she was known as Posterli, Quatemberca and Fronfastenweiber.

In southern Austria, in Carinthia among the Slovenes, a male form of Perchta was known as Quantembermann, in German, or Kvaternik, in Slovene (the man of the four Ember days). Grimm thought that her male counterpart or equivalent is Berchtold.

Regional variations of the name include Berigl, Berchtlmuada, Perhta-Baba, Zlobna Pehta, Bechtrababa, Sampa, Stampa, Lutzl, Zamperin, Pudelfrau, Zampermuatta and Rauweib.

Modern celebrations

In contemporary culture, Perchta is portrayed as a “rewarder of the generous, and the punisher of the bad, particularly lying children”.

Vestiges of devotion to Berchta survive in some Alpine villages where it is traditional to place offerings of food for her on rooftops so she finds them while riding by.

Today in Austria, particularly Salzburg, where she is said to wander through Hohensalzburg Castle at dead of night, the Perchten are still a traditional part of holidays and festivals (such as the Carnival Fastnacht). The wooden animal masks made for the festivals are today called Perchten.

In the Pongau region of Austria large processions of Schönperchten (“beautiful Perchten”) and Schiachperchten (“ugly Perchten”) are held every winter. Beautiful masks are said to encouraging financial windfalls, and the ugly masks are worn to drive away evil spirits.

Other regional variations include the Tresterer in the Austrian Pinzgau region, the stilt dancers in the town of Unken, the Schnabelpercht in the Unterinntal region and the Glöcklerlaufen (“bell-running”) in the Salzkammergut. A number of large ski-resorts have turned the tradition into a tourist attraction drawing large crowds every winter.

From: Encyclopedia of Spirits and Wikipedia

The dark powers emanate from the dark aspects of the Goddess and the God. This is the power of the Crone and the Lord of the Shadows; the Hag and the Hunter. The dark powers are more than just a personification of the negative influences in life, however, and the energy raised through the dark imagery of the Divine is very potent. As such, be careful what you do.

The Dark Goddess is manifested in mythology as various kinds of death crones, wise hags, devastation, war, disease and barrenness of the land. She is the Bone Mother who collects the skulls of the dead for the ossuary. In Irish mythology, Morrigan and Nemain would be considered Dark Goddesses in that they are associated with War and Death.

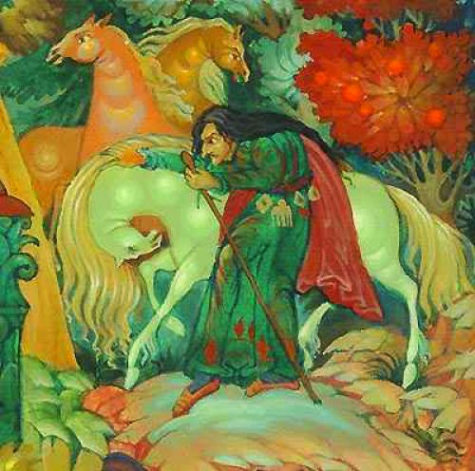

The Dark God is seen in mythology as the silent host to the dead in his underground realm of gray shadows and deep sleep, knowing of secrets and wise of the universe, death, war, destruction, gatherer of souls and harbinger of chaos. He is the Hunter, whose wild hunt, or raid, ingathers the energies of the soul.

There is sense to this ancient cosmology. Cults of ancient times focused on the dark aspects of the Divine so that their followers would move past their fear of mortality to seize upon the recognition of their eternal immortality.

In Irish mythology, Crom Cruach, and Donn would be considered “Dark Gods” or “Dark Powers” because Donn was the god of the dead Milsians. At death, Mannannan Mac Lyr carried the soul to Tech Dunn or the House of Donn. In texts like the Dinsenchus there is references to Crom being considered to be a dark god, contrasting a light god, in a way that is very similar to the Slavic god Czernobog.

As a power, the Dark Lord is the Chaos from which Order must evolve. Yet there is no ending to this cycle, Order resolves again as Chaos to be reborn as New Order. The Lord of Shadows as Death becomes the process of new life by gathering the energy of dying life, and the Passage into a new material form is through the Crone.

In the aspect of light, the god dies willingly by entering the ground to bring his vitality to crops that will be harvested to feed humanity. Through this selfless act, he revitalises the earth. He does this through the Crone. The marriage of Lugh in August, celebrated as Lughnasadh, is the start of the descent into Mother Earth. Once there, he is transformed into the son within the goddess. Hence, the pagan god is both Father and Son, which is yet another concept that Christianity absorbed from the pagans. The harvest comes, the seasons change, and the Mother becomes the Crone of Autumn and Winter, only to be transformed into Mother again at Winter Solstice with the rebirth of the Sun (her son, the god). See Also: Cernunnos, Green Man and Herne.

The womb-tomb is the domain of the Crone and is a place of great power. This is where the transformation takes place, with energies of death given repose and returned to form as the energies of life. When this power is confronted and recognised, there comes a freedom from fear, a new sense of independence and a recognition of personal responsibility. We are not judged in Death by the Lady and the Lord, but we are Self-judged. From the quietude of the realm, we move through her into new life. That is the balanced, pagan theme of the cauldron, the god of self-sacrifice and the resurrecting goddess. It is this power of the goddess that significantly differentiates the old and new religions.

Thus, in an historical sense, while the Dark Lord guides the chaos of social and cultural changes through the Crone into a new life, the Crone becomes not the terror of death, but the joyful passage to new vibrant societies through the death of the outmoded and stagnant ones. She is Fata Morgana, the Huntress Diana, Minerva, Cerridwen, Sati and Kali. He is Pluto, Hades, Cerunnos, Herne the Hunter, Set and Shiva. But the names may not convey the image needed by the practitioner unless you are able to move beyond the modern association of darkness as evil.

By accepting that the dark powers are in balance with the light powers, you are able to utilise the wholeness of the Power. The dichotomy of good and evil do not apply to what simply is. Energy can be drawn to the light or to the dark; thus death provides the soul’s passage to whichever realm the soul-energy has been drawn. Energy is always in motion, and flows back and forth between light and dark. What at one time is light energy turns and becomes dark energy. Through the practice of the Craft, the witch directs this energy for beneficial purpose. To do otherwise, is to inflict Self-harm.

To face the Underworld and the power of the dark aspect of the Divine is to understand that dark is part of the necessary blend of light and not something to fear. The unifying of the dark and the light within the individual offers wholeness and peace, which may then be transferred to external contacts.

From: Green Witchcraft II

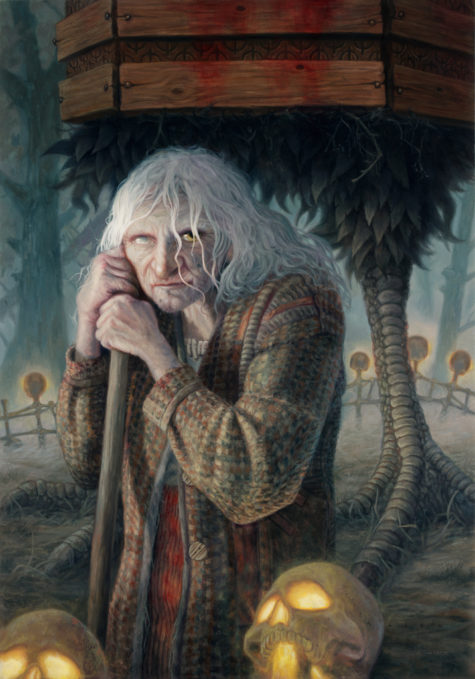

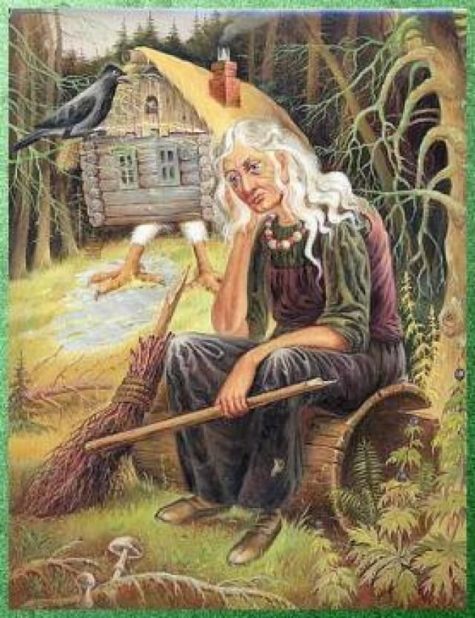

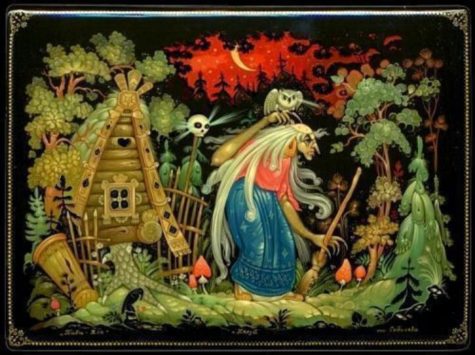

In Slavic folklore, Baba Yaga is a supernatural being (or one of a trio of sisters of the same name) who appears as a deformed and/or ferocious-looking woman. Baba Yaga flies around in a mortar, wields a pestle, and dwells deep in the forest in a hut usually described as standing on chicken legs (or sometimes a single chicken leg).

Baba Yaga may help or hinder those that encounter or seek her out. She offers comprehension, not comfort. She sometimes plays a maternal role, and also has associations with forest wildlife. She is a many-faceted figure, capable of inspiring those who seek to see her as a Cloud, Moon, Death, Winter, Snake, Bird, Pelican or Earth Goddess.

Baba Yaga is an enigmatic spirit who rules the conjunction of magic and harsh reality, of limits and possibilities. This Death Spirit provides fertility when she chooses, but she also consumes those who disappoint her. She is iron-toothed, boney-legged, and wears a necklace of human skulls. Her home is surrounded by a fence crafted from human bones and, when inside of her dwelling, she may be found stretched out over the stove, reaching from one corner of the hut to another.

Like her compatriot spirits, Kali and La Santisima Muerte, Baba Yaga encompasses all the mysteries of life and death; contemplate her in order to begin to comprehend these mysteries. I don’t suggest contacting her (the Baba has little patience; don’t waste her time without good reason), a kind of magical contemplation is recommended instead.

Connecting With Baba Yaga

The Baba Yaga’s Feast Day is usually celebrated on the first full moon in November, but a connection can be made at any time during the year.

- Build an altar featuring birch wood and leaves, animal imagery, a mortar, pestle and broom, and especially, food and drink.

- Baba Yaga is always voraciously hungry. Offer her real food or cut out photo images for the altar. She is especially fond of Russian extravagances like coulibiac.

- Offer her a samovar with blocks of fine Russian caravan tea and perhaps a water pipe.

- Sit with the altar, gaze at it from different angles, play with the objects and see what comes to mind.

Be patient, and expect that it will take time to achieve a connection and a response.

More About Baba Yaga

The ‘old woman’ of autumn was called Baba by the Slavic inhabitants of eastern Europe, Boba by the Lithuanians. This seasonal divinity lived in the last sheaf of grain harvested in a year, and the woman who bound it would bear a child that year. Baba passed into Russian folk legend as the awesome Baba Yaga, a witchlike woman who rowed through the air in a mortar, using a pestle for Her oar, sweeping the traces of Her flight from the air with a broom.

A prototype of the fairytale witch, Baba Yaga lived deep in the forest and scared passersby to death just by appearing to them. She then devoured Her victims, which is why Her picket fence was topped with skulls. Behind this fierce legend looms the figure of the ancient birth-and-death Goddess, one whose autumn death in the cornfield led to a new birth in spring.

Baba Yaga is a Slavic version of Kali, the Hindu Goddess of Death, the Dancer on Gravestones. Although, more often than not, we consider Baba Yaga as a symbol of death, She is a representation of the Crone in the Triple Goddess symbolism. She is the Death that leads to Rebirth. It is curious that some Slavic fairy tales show Baba Yaga living in Her hut with Her two other sisters, also Baba Yagas. In this sense, Baba Yaga becomes full Triple Goddess, representing Virgin, Mother, and the Crone.

Baba Yaga is also sometimes described as a guardian of the Water of Life and Death. When one is killed by sword or by fire, when sprinkled with the Water of Death, all wounds heal, and after that, when the corpse is sprinkled with the Water of Life, it is reborn. The symbolism of oven in the Baba Yaga fairy tales is very powerful since from primordial times the oven has been a representation of womb and of baked bread. The womb, of course, is a symbol of life and birth, and the baked bread is a very powerful the image of earth, a place where one’s body is buried to be reborn again.

It is interesting that Baba Yaga invites Her guests to clean up and eat before eating them, as though preparing them for their final journey, for entering the death, which will result in a new clean rebirth. Baba Yaga also gives Her prey a choice when She asks them to sit on Her spatula to be placed inside the oven: if one is strong or witty, he or she escapes the fires of the oven, for weak or dim-witted ones, the road to death becomes clear.”

Baba Yaga lives in the middle of a very deep forest, in a place which is often difficult to find unless a magic clue (a ball of yarn or thread) or a magic feather shows the way. The old hag lives in a wooden hut on two chicken legs (sometimes three or four legs are described).

Usually the hut is turned with its back towards a traveler, and only magical words can make it turn around on its chicken legs to face the newcomer. Very often, the hut revolves with loud noises and painful screams that make a visitor cringe. This serves to frighten the reader, showing the hut’s old age, and to show that Baba Yaga does not care about her hut’s well being.

- Baba Yaga fairy tales can be found at Widdershins.

It is also fascinating that some fairy tales describe the hut as being a unique evil entity: firstly, it has the ability to move on its chicken legs. Secondly, it understands human language and is able to decide whether and when to let a visitor enter its premises. Finally, the hut is often depicted as being able ‘to see’ with its eyes (its windows) and ‘to speak’ with its mouth (its doorway). I also cannot help feeling that the hut is able ‘to think’, and one can observe these thoughts as wild powerful clouds of steam emerging from the hut’s chimney. What powerful imagery!

Baba Yaga’s hut is often surrounded by fence made of human bones and topped with human skulls with eyes. Instead of wooden poles onto which the gates are hung, human legs are used; instead of bolts, human hands are put in; instead of the keyhole, a mouth with sharp teeth is mounted. Very often Baba Yaga has her hut is protected by hungry dogs or is being watched over by evil geese-swans or is being guarded by a black cat. The gates of Baba Yaga’s villa are also often found to be guardians of Yaga’s hut as they either lock out or lock in the Witch’s prey.

Baba Yaga – The Black Goddess – An Essay

For those of you who enjoy a more scholarly approach to the goddess, here is an essay by an anonymous author about Baba Yaga, the Black Goddess, and what her mythology represents.

Baba Yaga and her Magical Colts

I have been thinking and thinking about the image and story of Baba Yaga now for months and wondering how girls and women can resolve the seemingly paradoxical story of a bony heartless witch with the image of innocence of a rejected and abandoned girl. The following essay outlines how we use myth and story to perpetuate unconscious mindsets and it also unveils the gifts that these stories unfold in our inner psyche.

The story of Baba Yaga is prime among many images of the Black Goddess. The Black Goddess is at the heart of all creative processes and cannot be so easily viewed. Men and women rarely approach her, except in fear. Women are learning of her through the strength and boldness of elder women who are not afraid to unveil her many faces.

Sofia as wisdom lies waiting to be discovered within the Black Goddess who is her mirror image. Knowing that, until we make that important recognition, we are going to have to face the hidden and rejected images of ourselves again and again.

As women, we are confronted throughout our lives with unavoidable body messages regarding the uniqueness of our form and the inevitable changes that characterize aging and the passage of time. Although aging presents difficult challenges for both men and women, women confront some specific difficulties because of their gender. In traditional narratives, the end of biological fertility has relegated women to the status of “old women” who are stereotypically viewed as poor, powerless, and pitiful in our sexist and youth oriented culture. Baba Yaga, often referred to as the Black Goddess, and Vasalisa, often representing Sophia, are intrinsic to the psyche of girls and women because they shows us that the illusion of form can hide wonderful qualities within.

Baba Yaga, ugly, haglike, flying in her mortar,

seemingly isolated and abandoned,

yet broom at hand, ready to sweep the clouds across the skies

and reveal her hidden cosmic nature

One of the cruelest of stereotypes that older women face is the “menopausal woman.” These are accentuated by the very fact that younger women are often rejecting or distancing to older women in society, unwilling to identify with women older than themselves. These experiences are painful confirmations that the aging woman no longer meets the social criteria of a physically and securely attractive woman. The common result for most women is the activation of shame — as if becoming/looking older means that something is deeply and truly wrong with oneself.

Conscious femininity is a cyclic process and involves an awakened awareness of the triple form of the Goddess – Mother, Virgin and Crone – and how she exists simultaneously and continuously in all of our psyches, each taking center stage in awareness at different moments. These archetypal patterns are considered intrapsychic modes of consciousness in the individual, and the primordial image of a powerful and integrated woman, crowned with wisdom gleaned through real experience, is again reemerging through both the individual and collective psyches of humanity.

First, however, women must learn to embrace, respect and honor their changing bodies, abilities, capacities and WISDOM. We can learn a lot from Baba Yaga!

An archetype is a universal symbol, an inherited mental image to which humankind responds, and which is often acted upon as an unconscious reaction to human experience. These stories are no different and the story of Baba Yaga exemplify this phenomena.

The female experience is symbolized by and archetypally corresponds with the ancient Triple Goddess as the creator and destroyer of all life — “the ancient and venerable female divinity embodying the whole of female experience as Virgin, Mother, Crone.” The archetypal figure representing the end of a woman’s childbearing years, or the “third age” for women, is the third aspect of the Triple Goddess, the Crone.

At the climacteric or menopause, women are often forced to stand precipitously between the culmination of past experiences, to realize that youth is left behind, and prepare a new space within whereby a fresh image will coalesce as she envisions her future. This is real labor. The traditional constructs that are available to women are largely influenced by patriarchal standards of youth and beauty and we need fresh constructs that honor the diversity of life in all of its forms.

When a culture’s language has no word to connote “wise elder woman,” what happens to the women who carry the “Grandmother” consciousness for the collective? Prejudicial (prejudged) attacks throughout history against older women symbolized patriarchy’s feminization of fear: the ultimate fear of annihilation, to be nonexistent (no existence). Centuries-long indoctrination limits our imagination so that we see this ancient aspect of the feminine only in her negative forms. We see her as the one who brings death to our old way of being, to our lives as we have known them, and to our embodied selves.

Our fear of the unconscious makes the Crone or Baba into an image of evil. The prevalence of paranoid masochism finds its expression through feminine perversion. Kristeva writes from “Stabat Matar” that: “Feminine perversion is coiled up in the desire for law as desire for reproduction and continuity, it promotes feminine masochism to the rank of structure stabilizer.” Structure stabilizer! Natural death is to be feared, hidden away, certainly not recognized as part of the natural rhythm of cycles of birth, death and rebirth?

Only when death becomes projected does it become a monster to be feared. There is an unconscious belief that a woman who has outlived her husband has somehow used up his life force. Walker claims that the secret hidden in the depths of men’s minds is that images of women are often identified with death. Women have also bought into this mindset largely because of lost connection with their own spirituality and the natural cycles of nature!

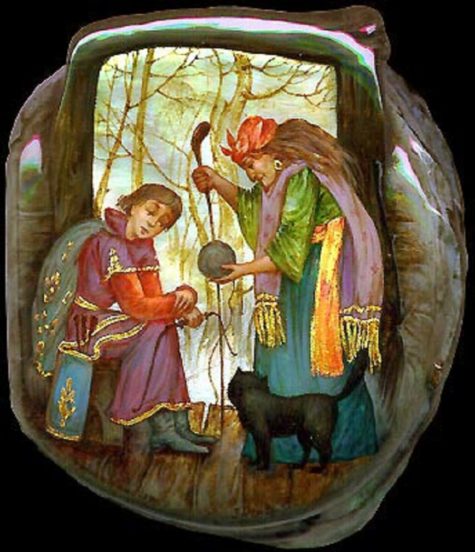

Vasalisa Approaching the Hut of Baba Yaga

To be sent to Baba Yaga was tantamount to being sent to one’s death, but Vasalisa was actually helped by Baba Yaga. By facing her own worst fear — death itself, Vasalisa became liberated from her previous situation and immaturity.

The myths of our society tell us much about the attitudes and world view of the myth-owners, and these attitudes are the products of women’s roles within the wider society. Myth arises out of the collective level of humankind’s experience, which is presented through images and symbols that resonate within our psyche. It is something we inherit from our ancestors and it is expressed through our genetic, racial memory. Kaufert reminds us however, that “myth is a system of values presented as if it were a system of facts.”

The symbol of the Crone is unique to a feminine worldview where the face of the Virgin and the fecund Mother, the Virgin Mother Mary, was absorbed in Western tradition into Judeo-Christian imagery. Likewise, we see the image of Vasalisa embodied as this innocence. The Crone has retained much of her pre-patriarchial character where she has haunted the fringes of Western culture, largely ignored, unacknowledged and rejected; one that often strikes fear into the hearts of men and some women because she has tremendous power and cannot be confined.

“Wise women,” in the past, were literally seen as having the power of life and death. They symbolized maturity, authority, attuned to nature and instinct. They were women whom men could not bind by making pregnant. They personified, as Hall writes:

“That aspect of life that men would most like to control but against which they are powerless: death. The Crone was healer, seer, medicine woman and, when death arrived with inexorable certainty, she was the mid-wife for the transition to another life.”

Baba Yaga’s Hut standing on its magical Chicken-Leg,

yet revolving like the solar symbol it is,

always rising and setting in a new place,

bringing birth — and death — daily.

Over time, and in recent history the Crone became associated with the dark side of the feminine; the withered old hag, the witch. Ironically, the word “Hag” used to mean “holy one” from the Greek hadia, as in hagiolatry, “worship of saints.” And during the middle ages hag was said to mean the same as fairy.

In deconstructing these familiar images of the older aging woman, we must first identify their symbolic roots and challenge them in order to allow for potent, vital images that energize women’s potential creative spiritual evolution. In this quest it is crucial to find valued female images that present creative and spiritual power, that offer a paradigm of ongoing formation and integration. If we do not do so, we risk encountering images of women that reinforce stereotypical models and moreover, can only alienate us from our own truest selves.

The Crone is a figure who incorporates both dark and light, life and death, creation and destruction, form and dissolution. The doll [Vasalisa’s doll, given to her by her dying mother] becomes the symbol of the Sibyl, a figure of inspiration and intuition. She acts as a guide through the great passages of life, leading a woman into her own inner knowing.

Vasalisa and her doll with the White Horseman of Dawn(who reports daily to Baba Yaga, just like the Red Horseman of Noon, and the Black Horseman of Evening)

We see this in the story of Vasalisa and Baba Yaga, the innocence of the maiden coming of age through a series of tasks. Baba Yaga forces Vasalisa to look within through intuition (the doll) and she awakens to the illuminating light that is carried in her heart. Within the simple limits of a folk story, the interactions of Sophia (Vasalisa) and the Black Goddess (Baba Yaga) are demonstrated. Baba Yaga or the Crone also embodies the inner archetype of Sophia, feminine wisdom.

Hall writes: “Sophia is a Wise Woman, one who epitomizes feminine thought. This thought is of a particular kind. It is ‘gestalt’ or whole perception; it synthesizes and looks at the overall pattern; it is logical but empathetic, and combines acute observation with intuition. It is relational (taking account of the past in order to project forward into the future), and it arises out of care and concern for man and womankind. It uses both the left and right brain modes of thought. It is creative and concerned with vision and solutions — attributes which are an integral part of the Wise Woman.”

Sophia plays, hides, adepts, disguises, and brings justice. Interestingly, we see these very same qualities attributed to the wise woman as being Vasalisa’s, only not fully formed. Thus affirming the feminist perspective of the Goddess in all of her aspects and that all ways to wisdom are valid paths. Girls and women are encouraged to rely on their own subjective experience or on the communal experience of other women This is a very important point!

From a feminist perspective, the entry into the third phase of women’s life is seen as a time of spiritual questing, renewal and self-development. It is a time where women are encouraged to explore themselves through interaction with other females who are providers of friendship, support, love, even sexual satisfaction, rather than a woman’s family.

Baba Yaga helping young Ivanushka

Likewise, the young girl growing into maidenhood needs the guidance and wisdom that elder women can provide. She must receive the gifts that the wise ones can give her. Baba Yaga may appear as a witch, yet she is instrumental in folk traditions. She aids heroes to find weapons, simplifying tasks and quests when she is treated with courtesy. Her transposed reflection is none other than Vasilisa the fair – the young righteous maiden who defeats her opposite aspect by truth and integrity.

The older woman is the keeper of the wisdom and tradition in her family, clan, tribe, and community. She is the keeper of relations, whether they be interpersonal or with all of nature. Every issue is an issue of relationship. It is assumed that she has a deep understanding of the two great mysteries, birth and death.

Another quality is the ability to be mediator between the world of spirit and earth. She is emancipated from traditional female roles of mothering and is free to make a commitment to the greater community. As a result of this freedom, there is an abundance of creativity unleashed in this phase of life; often expressed through art, poetry, song, dance, and crafts, and through her sexuality as she celebrates her joy (Joussance).

This elder time must again become a stage of life revered and honored by others and used powerfully in service by women themselves. The elder “Wise-woman” can represent precisely the kind of power women so desperately need today, and do not have: the power to force the hand of the ruling elite to do what is right, for the benefit of future generations and of the earth itself.

A powerful Baba Yaga, flying in her mortar,

protecting her forests, and banishing all obstacles with her pestle and broom.

Like Baba Yaga, the Crone must help us by her example and “admonish us to revere all peoples and all circles of life upon this earth . . . not only important for the dignity and self-esteem of each woman, but vital for the countenance of life on our sweet Mother Earth.” Since men define power as the capacity to destroy, the Destroying Mother Crone must be the most powerful female image for them, therefore, the only one likely to force them (us) in any new direction.

A woman who denies her life process at any time in her development, clinging desperately to outmoded images, myths and rituals of her past, obscures her connection with Self, the Divine, and therefore, with her spiritual heritage, the natural universe. The same holds true for our daughters, maidens who are coming of age. There is a kind of internal balance and sense of holiness available to us when we accept ourselves as part of a world that honors cycles, changes, decay and rebirth. It is time for women to reflect and give form to the authentic self in its evolving, formative process.

The woman who is willing to make that change must become pregnant with herself, at last. She must bear herself, her third self, her old age with labor. There are not many who will help her with that birth. To Crone is to birth oneself as “Wise-woman,” and see the world through new eyes.

We have not had the safety valve of feminine metaphor in our spiritual understanding; consequently, the Feminine, both Divine and human, have appeared monstrously contorted, threatening and uncontrollable.

The Black Goddess lies at the basis of Spiritual knowing, which is why her image continuously appears within many traditions as the Veiled Goddess, the Black Virgin, the Outcast Daughter, the Wailing Widow, the Dark Woman of Knowledge.

The way of Sophia is the way of personal experience. It takes us into the realm of “magical reality,” those areas of our lives where extraordinary vocational and creative skills are called upon to manifest. Those treasures of Baba Yaga and Vasalisa lie deep within each of us, waiting to be discovered.

Baba Yaga and Vasalisa,

Crone and Puella [Maiden]: Two Aspects of One Archetype

Sources:

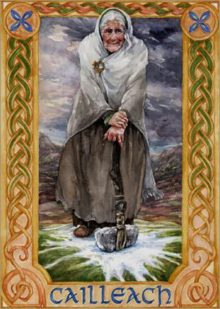

This Neolithic goddess, known variously as the “blue hag”, the “Bear goddess” and “Boar goddess”, “owl faced”, and “ancient woman”, has survived through the ages. Coming from the continent, Her worship spread to the British Isles early after the recession of the glaciers. The proto-Celtic peoples honored Cailleach and blended Her varying aspects, creating images invoking both love and terror. The various names (see below) that Cailleach has been worshipped in lend a clue to Her wide spread worship:

Names: Beare, Béarra, Béirre, Bhéara, Bheare, Bhéirre, Bhérri, Boi, Bui, Cailliaech, Cailliach, Cailleach Beara, Caillech Bherri, Calliagh Birra, Cally Berry, Carline, Digde, Dige, Dirra, Dirri, Duineach, Hag of Beara, Hag of Beare, Mag-Moullach, Mala Liath, Nicnevin, and Scotia,

Titles: Ancient Woman, Bear goddess, Blue Hag, Boar Goddess, Creator of Storms, Crone, Duineach, Goddess of Sovereignty, Many Followers, Old Woman, Owl Faced, and The Popular

The Cailleach Beara is one of the oldest living mythological beings associated with Ireland. According to the ancient stories, she has a conversation with Fintan the Wise and the Hawk of Achill and both agree that she has outlived them, saying ‘Are you the one, the grandmother who ate the apples in the beginning?’ (apples are associated with immortality and are considered the food of the gods)

The Cailleach Beara is ever-renewing and passes through many lifetimes going from old age to youth in a cyclic fashion. She is reputed to have had at least fifty foster children during her ‘lives’. She usually appears as an old woman who asks a hero to sleep with her, if the hero agrees to sleep with the old hag she then transforms into a beautiful woman.

In Scotland, where she is also known as Beira, Queen of Winter, she is credited with making numerous mountains and large hills, which are said to have been formed when she was striding across the land and accidentally dropped rocks from her apron. In other cases she is said to have built the mountains intentionally, to serve as her stepping stones. She carries a hammer for shaping the hills and valleys, and is said to be the mother of all the goddesses and gods.

She is considered to be the daughter of Grainne, or the Winter Sun. She is affectionately known as ‘Grandmother of the Clanns’ and ‘the Ancestress of the Caledonii Tribe’. The legends of the Caledonii tribe speak of the “Bringer of the Ice Mountains”, the great blue Old Woman of the highlands. Called Cailleach, Cailleach Bheur, Scotia, Carline or Mag-Moullach by the people, She was the Beloved Mountain Giantess who protected the early tribe from harm and nurtured them in Her sacred mountains.

The Cailleach Beara is usually associated with Munster in particular Kerry and Cork. Her grandchildren and great-grandchildren formed the tribes of Kerry and it’s surroundings. And she is considered a goddess of sovereignty giving the kings the right to rule their lands.

Traits and Abilities:

She herds deer. She fights Spring. Her staff freezes the ground.

She is sometimes depicted as an old hag with the teeth of a wild bear and boar’s tusks or else is depicted as a one-eyed giantess who leaps from peak to peak, wielding Her magical white rod and blasting the vegetation with frost. Cailleach’s white rod, or slachdan, made of birch, bramble, willow or broom, is a Druidic rod which gives Her power over the weather and the elements.

Cailleach is also a goddess who governs dreams and inner realities. She is the goddess of the sacred hill, the Sidhe, and the place where we enter into the hidden realm of the Fey and spirit beings. Sacred stones, the bones of the earth, are Her special haunts. Cailleach is connected to the ‘bean sidhe’ or banshee (which means ‘supernatural woman’) who are the wild women of the Fey.

In Scotland, the Cailleachan (‘old women’) were also known as The Storm Hags, and seen as personifications of the elemental powers of nature, especially in a destructive aspect. They were said to be particularly active in raising the windstorms of spring, during the period known as A’ Chailleach.

Là Fhèill Brìghde is the day the Cailleach gathers her firewood for the rest of the winter. Legend has it that if she intends to make the winter last a good while longer, she will make sure the weather on February 1 is bright and sunny, so she can gather plenty of firewood to keep herself warm in the coming months. As a result, people are generally relieved if February 1 is a day of foul weather, as it means the Cailleach is asleep, will soon run out of firewood, and therefore winter is almost over.

On the Isle of Man, where She is known as Caillagh ny Groamagh, the Cailleach is said to have been seen on St. Bride’s day in the form of a gigantic bird, carrying sticks in her beak

On the west coast of Scotland, the Cailleach ushers in winter by washing her great plaid (tartan) in the Whirlpool of Coire Bhreacain (cauldron of the plaid). . This process is said to take three days, during which the roar of the coming tempest is heard as far away as twenty miles inland. When she is finished, her plaid is pure white and snow covers the land.

Cailleach is also the guardian spirit of a number of animals. She is associated with the ancient tradition of herding reindeer. This means that the reindeer (and all deer) are Her cattle; She herds and milks them and often gives them protection from hunters. Swine, wild goats, wild cattle, and wolves are also Her creatures. Cailleach is also a fishing goddess, as well as the guardian of wells and streams.

Related Content: