Fairy Tales and Stories

The Case of the Abbot Gilbert

From the book Werwolves, by Elliott O’Donnell, first published in 1912, we have this account of the case of the Abbot Gilbert of the Arc Monastery, on the banks of the Loire.

Gilbert had been to a village fair, where the good vintage and hot sun combined had proved so trying that on his way home, through a dense and lonely forest, he had gone to sleep and been thrown from his horse. In falling he had bruised and cut himself so prodigiously that the blood from his wounds attracted to the spot a number of big wild cats.

Taken at a strong disadvantage, and without any weapons to defend himself, Gilbert would soon have fallen a victim to the ferocity of these savage creatures had it not been for the opportune arrival of a werwolf. A desperate battle at once ensued, in which the werwolf eventually gained the victory, though not without being severely lacerated.

Despite Gilbert’s protestations, for he was loath to be seen in such strange company, the werwolf accompanied him back to the monastery, where, upon hearing the Abbot’s story, it was enthusiastically welcomed and its wounds attended to.

At dawn it was restored to its natural shape, and the monks, one and all, were startled out of their senses to find themselves in the presence of a stern and awesome dignitary of the Church, who immediately began to lecture the Abbot for his unseemly conduct the previous day, ordering him to undergo such penance as eventually, robbing him of half his size and all his self-importance, led to his resignation.

The Opening Of The Egg

On the evening of the third day, I kneel down on the rug and carefully open the egg. Something resembling smoke rises up from it and suddenly Izdubar is standing before me, enormous, transformed, and complete. His limbs are whole and I find no trace of damage on them. It’s as if he had awoken from a deep sleep. He says:

Where am I? How narrow it is here,

how dark, how cool ~ am I in the grave? Where was I?

It seemed to me as if I had been outside in the universe ~

over and under me was an endlessly dark star-glittering sky ~

and I was in a passion of unspeakable yearning.

Streams of fire broke from my radiating body ~

I surged through blazing flames ~

I swam in a sea that wrapped me in living fires ~

Full of light, full of longing, full of eternity ~

I was ancient and perpetually renewing myself ~

Falling from the heights to the depths,

and whirled glowing from the depths to the heights ~

hovering around myself amidst glowing clouds ~

as raining embers beating down like the foam of the surf,

engulfing myself in stifling heat ~

Embracing and rejecting myself in a boundless game ~

Where was I? I was completely sun.

~Carl Jung

The God is in the egg.

Take your God with you. Bear him down to your dark land where people live who rub their eyes each morning and yet always see only the same thing and never anything else. Bring your God down to the haze pregnant with poison, but not like those blinded ones who try to illuminate the darkness with lanterns which it does not comprehend.

Instead, secretly carry your God to a hospitable roof. The huts of men are small and they cannot welcome the God despite their hospitality and willingness. Hence do not wait until rawly bungling hands of men hack your God to pieces, but embrace him again, lovingly, until he has taken on the form of his first beginning.

Let no human eye see the much loved, terribly splendid one in the state of his illness and lack of power. Consider that your fellow men are animals without knowing it. So long as they go to pasture, or lie in the sun, or suckle their young, or mate with each other, they are beautiful and harmless creatures of dark Mother Earth. But if the God appears, they begin to rave, since the nearness of God makes people rave. They tremble with fear and fury and suddenly attack one another in fratricidal struggles, since one senses the approaching God in the other.

So conceal the God that you have taken with you. Let them rave and maul each other. Your voice is too weak for those raging to be able to hear. Thus do not speak and do not show the God, but sit in a solitary place and sing incantations in the ancient manner:

Set the egg before you, the God in his beginning.

And behold it.

And incubate it with the magical warmth of your gaze.

HERE THE INCANTATIONS BEGIN.

Christmas has come. The God is in the egg.

I have prepared a rug for my God, an expensive red the land of morning.

He shall be surrounded by the shimmer of magnificence of his Eastern land.

I am the mother, the simple maiden, who gave birth and did not know how.

I am the careful father, who protected the maiden.

I am the shepherd, who received the message as he guarded his herd at night on the dark fields.

I am the holy animal that stood astonished and cannot grasp the becoming of the God.

I am the wise man who came from the East, suspecting the miracle from afar.

And I am the egg that surrounds and nurtures the seed of the God in me.

The solemn hours lengthen.

And my humanity is wretched and suffers torment.

Since I am a giver of birth.

Whence do you delight me, Oh God!

‘He is the eternal emptiness and the eternal fullness.

Nothing resembles him and he resembles everything.

Eternal darkness and eternal brightness.

Eternal below and eternal above.

Double nature in one.

Simple in the manifold.

Meaning in absurdity.

Freedom in bondage.

Subjugated when victorious.old in youth.

Yes in no.

Oh

light of the middle way,

enclosed in the egg,

embryonic,

full of ardor, oppressed.

Fully expectant,

dreamlike, awaiting lost memories.

As heavy as stone, hardened.

Molten, transparent.

Streaming bright, coiled on itself.

Amen, you are the lord of the beginning.

Amen, you are the star of the East.

Amen, you are the flower that blooms over everything.

Amen, you are the deer that breaks out of the forest.

Amen, you are the song that sounds far over the water.

Amen, you are the beginning and the end.

One word that was never spoken.

One light that was never lit up.

An unparalleled confusion.

And a road without end.

I forgive myself these words, as you also forgive me for wanting your blazing light.

Rise up, you gracious fire of old night.

I kiss the threshold of your beginning.

My hand prepares the rug and spreads abundant red flowers before you.

Rise up my friend, you who lay sick, break through the shell.

We have prepared a meal for you.

Gifts have been prepared for you.

Dancers await you.

We have built a house for you.

Your servants stand ready.

We drove herds together for you on green fields.

We filled your cup with red wine.

We set out fragrant fruit on golden dishes.

We knock at your prison and lay our ears against it.

The hours lengthen, tarry no longer.

We are wretched without you and our song is worn out.

We are miserable without you and wear out our songs.

We spoke all the words that our heart gave us.

What else do you want?

What else shall we fulfill for you?

We open every door for you.

We bend our knees where you want us to.

We go to all points of the compass according to your wish.

We carry up what is below, and we turn what is above into what is below,as you command.

We give and take according to your wish.

We wanted to turn right, but go left, obedient to your sign.

We rise and we fall,

we sway and we remain still,

we see and we are blind,

we hear and we are deaf,

we say yes and no,

always hearing your word.

We do not comprehend and we live the incomprehensible.

We do not love and we live the unloved.

And we evolve around ourselves again and comprehend and live the understandable.

We love and live the loved, true to your law.

Come to us, we who are willing from our own will.

Come to us, we who understand you from our own spirit.

Come to us, we who will warm you at our own fire.

Come to us, we who will heal you with our own art.

Come to us, we who will produce you out of our own body.

Come, child, to father and mother.

We asked earth.

We asked Heaven.

We asked the sea.

We asked the wind.

We asked the fire.

We looked for you with all the peoples.

We looked for you with all the kings.

We looked for you with all the wise.

We looked for you in our own heads and hearts.

And we found you in the egg.

I have slain a precious human sacrifice for you,a youth and old man.

I have cut my skin with a knife.

I have sprinkled your altar with my own blood.

I have banished my father and mother so that you can live with me.

I have turned my night into day and went about at midday like a sleepwalker.

I have overthrown all the Gods, broken the laws, eaten the impure.

I have thrown down my sword and dressed in women’s clothing.

I shattered my firm castle and played like a child in the sand.

I saw warriors form into line of battle and I destroyed my suit of armor with a hammer.

I planted my field and let the fruit decay.

I made small everything that was great and made everything great that was small.

I exchanged my furthest goal for the nearest, and so I am ready.

However, I am not ready, since I have still not accepted that which chokes my heart. That fearful thing is the enclosing of the God in the egg. I am happy that the great endeavor has been successful, but my fear made me forget the hazards involved. I love and admire the powerful. No one is greater than he with the bull’s horns, and yet I lamed, carried, and made him smaller with ease. I almost slumped to the ground with fear when I saw him, and now I rescue him with a cupped hand. These are the powers that make you afraid and conquer you; these have been your Gods and your rulers since time immemorial: yet you can put them in your pocket.

What is blasphemy compared to this? I would like to be able to blaspheme against the God: That way I would at least have a God whom I could insult, but it is not worth blaspheming against an egg that one carries in one’s pocket. That is a God against whom one cannot even blaspheme.

I hated this pitifulness of the God. My own unworthiness is already enough. It cannot bear my encumbering it with the pitifulness of the God. Nothing stands firm: you touch yourself and you turn to dust. You touch the God and he hides terrified in the egg. You force the gates of Hell: the sound of cackling masks and the music of fools approaches you. You storm Heaven: stage scenery totters and the prompter in the box falls into a swoon. You notice: you are not true, it is not true above, it is not true below, left and right are deceptions. Wherever you grasp is air, air, air.

But I have caught him, he who has been feared since time immemorial; I have made him small and my hand surrounds him. That is the demise of the Gods: man puts them in his pocket. That is the end of the story of the Gods. Nothing remains of the Gods other than an egg. And I possess this egg. Perhaps I can eradicate this last one and with this finally exterminate the race of Gods. Now that I know that the Gods have yielded to my power – what are the Gods to me now? Old and overripe, they have fallen and been buried in an egg.

~Carl Jung, Liber Novus

Strange Days

“There are a hundred things she has tried to chase away the things she won’t remember and that she can’t even let herself think about because that’s when the birds scream and the worms crawl and somewhere in her mind it’s always raining a slow and endless drizzle.

You will hear that she has left the country, that there was a gift she wanted you to have, but it is lost before it reaches you. Late one night the telephone will sign, and a voice that might be hers will say something that you cannot interpret before the connection crackles and is broken.

Several years later, from a taxi, you will see someone in a doorway who looks like her, but she will be gone by the time you persuade the driver to stop. You will never see her again.

Whenever it rains you will think of her. ”

― Neil Gaiman

When King Laugh Come

“It is a strange world, a sad world, a world full of miseries, and woes, and troubles. And yet when King Laugh come, he make them all dance to the tune he play. Bleeding hearts, and dry bones of the churchyard, and tears that burn as they fall, all dance together to the music that he make with that smileless mouth of him.

Ah, we men and women are like ropes drawn tight with strain that pull us different ways.

Then tears come, and like the rain on the ropes, they brace us up, until perhaps the strain become too great, and we break. But King Laugh he come like the sunshine, and he ease off the strain again, and we bear to go on with our labor, what it may be.”

~Dr. Seward’s recollection of his conversation w/ Van Helsing ― Bram Stoker, Dracula

The Storyteller

The little boy stumbled through the forest. He was sure that wild animals were chasing him, and wanted to eat him. As he crashed through the undergrowth he suddenly emerged into a clearing. He looked around, fearing that he could hear animals, but all was quiet.

The little boy walked further into the clearing. He saw a small stool with a book on it.

He stopped, and looked around wondering who had left the stool, and the book there.

He walked over to the stool, and picked up the book to look at it. Without thinking, he sat down, and opened the book. He started to read aloud. The only sound in the clearing was the little boy’s voice.

He had forgotten about his earlier fear, and he had also stopped imagining that he could hear animals after him.

Once he had finished reading the story he put the book down, and he said to the clearing, “I’ll come back tomorrow to read again.”

The little boy left the clearing and reentered the forest. He wasn’t afraid anymore. It was if he had a new found confidence, and manner.

The next day he returned, and found a different book on the stool, and as before, he sat down, and started to read.

This went on for a week. After seven days animals started to come through the undergrowth, and entered the clearing. When they saw the boy, and heard his storytelling they would stop, find a place to sit down, and listen to him.

One day he heard a roar behind him, and the little boy turned around, coming face to face with a tiger. “Shhh!” he told the tiger, and gave it a smack across the nose.

The tiger was taken aback, but he did as he was told and he went to a tree. Then he too, sat and listened to the little boy.

This went on for many years, and some animals died never to return, while others grew old as the little boy did. One day, when the little boy was no more but a little old man he died as he was reading one of his stories.

The animals looked up, and listened to the silence.

Wild dogs howled, elephants trumpeted their calls, birds tweeted and chirped, monkeys chatted and tigers roared as one.

The tiger, who many years ago the little boy had smacked across the nose, carried the little boy, and laid him to rest under his tree.

The animals lined up to pay their respects to the little boy who had devoted his life to reading to the animals.

As they lined up they were watched by God, Buddha, Allah and Ganesha, standing off to the side, who had tears in their eyes, not because the little boy that had died, who now stood next to them, but because as each animal came to the body of the little boy, each animal would lay their head down on his chest, and shed tears over the boy’s body.

Finally a small baby elephant came, and laid his head, and trunk down on the little boy’s body, and his tears flowed over the little boy’s chest.

When the animals had left, there was an eerie silence over the clearing.

Many, many years passed until one day, a small girl come running through the bushes, with a frightened look on her face. She stopped, and looked around the clearing. She saw a small stool, and so she walked over to it, wondering who would leave such a thing here in the forest.

She sat down on the stool and looked down. She saw a box full of books.

The little boy smiled.

― Anthony T. Hincks

The Witch-Cat of the Ozarks

A drunken braggart accepted a dare to sleep in a house that had once been used by witches. At midnight, when he had finished his jug of whisky and was just beginning to fall asleep, an enormous cat suddenly appeared.

It howled and spat at him, so he shot at it with his hunting gun and, though it escaped, he was certain he had shot one of its paws clean off. At that moment a woman’s scream was heard in the distance, and just as the candle went out, the man saw a woman’s bare and bloody foot wriggling around on the table.

The following day he learned that a woman who lived nearby had accidentally shot her foot off and had died from loss of blood. It is said that she died howling and spitting like a cat.

Found at: Moggycats Cat Pages

The Juniper Tree

Long ago, at least two thousand years, there was a rich man who had a beautiful and pious wife, and they loved each other dearly. However, they had no children, though they wished very much to have some, and the woman prayed for them day and night, but they didn’t get any, and they didn’t get any.

In front of their house there was a courtyard where there stood a juniper tree. One day in winter the woman was standing beneath it, peeling herself an apple, and while she was thus peeling the apple, she cut her finger, and the blood fell into the snow.

“Oh,” said the woman. She sighed heavily, looked at the blood before her, and was most unhappy. “If only I had a child as red as blood and as white as snow.” And as she said that, she became quite contented, and felt sure that it was going to happen.

Then she went into the house, and a month went by, and the snow was gone. And two months, and everything was green. And three months, and all the flowers came out of the earth. And four months, and all the trees in the woods grew thicker, and the green branches were all entwined in one another, and the birds sang until the woods resounded and the blossoms fell from the trees. Then the fifth month passed, and she stood beneath the juniper tree, which smelled so sweet that her heart jumped for joy, and she fell on her knees and was beside herself. And when the sixth month was over, the fruit was thick and large, and then she was quite still. And after the seventh month she picked the juniper berries and ate them greedily.

Then she grew sick and sorrowful. Then the eighth month passed, and she called her husband to her, and cried, and said, “If I die, then bury me beneath the juniper tree.” Then she was quite comforted and happy until the next month was over, and then she had a child as white as snow and as red as blood, and when she saw it, she was so happy that she died.

Her husband buried her beneath the juniper tree, and he began to cry bitterly. After some time he was more at ease, and although he still cried, he could bear it. And some time later he took another wife.

He had a daughter by the second wife, but the first wife’s child was a little son, and he was as red as blood and as white as snow. When the woman looked at her daughter, she loved her very much, but then she looked at the little boy, and it pierced her heart, for she thought that he would always stand in her way, and she was always thinking how she could get the entire inheritance for her daughter.

And the Evil One filled her mind with this until she grew very angry with the little boy, and she pushed him from one corner to the other and slapped him here and cuffed him there, until the poor child was always afraid, for when he came home from school there was nowhere he could find any peace.

One day the woman had gone upstairs to her room, when her little daughter came up too, and said, “Mother, give me an apple.”

“Yes, my child,” said the woman, and gave her a beautiful apple out of the chest. The chest had a large heavy lid with a large sharp iron lock.

“Mother,” said the little daughter, “is brother not to have one too?”

This made the woman angry, but she said, “Yes, when he comes home from school.”

When from the window she saw him coming, it was as though the Evil One came over her, and she grabbed the apple and took it away from her daughter, saying, “You shall not have one before your brother.”

She threw the apple into the chest, and shut it. Then the little boy came in the door, and the Evil One made her say to him kindly, “My son, do you want an apple?” And she looked at him fiercely.

“Mother,” said the little boy, “how angry you look. Yes, give me an apple.”

Then it seemed to her as if she had to persuade him. “Come with me,” she said, opening the lid of the chest. “Take out an apple for yourself.” And while the little boy was leaning over, the Evil One prompted her, and crash! she slammed down the lid, and his head flew off, falling among the red apples.

Then fear overcame her, and she thought, “Maybe I can get out of this.” So she went upstairs to her room to her chest of drawers, and took a white scarf out of the top drawer, and set the head on the neck again, tying the scarf around it so that nothing could be seen. Then she set him on a chair in front of the door and put the apple in his hand.

After this Marlene came into the kitchen to her mother, who was standing by the fire with a pot of hot water before her which she was stirring around and around.

“Mother,” said Marlene, “brother is sitting at the door, and he looks totally white and has an apple in his hand. I asked him to give me the apple, but he did not answer me, and I was very frightened.”

“Go back to him,” said her mother, “and if he will not answer you, then box his ears.”

So Marlene went to him and said, “Brother, give me the apple.” But he was silent, so she gave him one on the ear, and his head fell off. Marlene was terrified, and began crying and screaming, and ran to her mother, and said, “Oh, mother, I have knocked my brother’s head off,” and she cried and cried and could not be comforted.

“Marlene,” said the mother, “what have you done? Be quiet and don’t let anyone know about it. It cannot be helped now. We will cook him into stew.”

Then the mother took the little boy and chopped him in pieces, put him into the pot, and cooked him into stew. But Marlene stood by crying and crying, and all her tears fell into the pot, and they did not need any salt.

Then the father came home, and sat down at the table and said, “Where is my son?” And the mother served up a large, large dish of stew, and Marlene cried and could not stop.

Then the father said again, “Where is my son?”

“Oh,” said the mother, “he has gone across the country to his mother’s great uncle. He will stay there awhile.”

“What is he doing there? He did not even say good-bye to me.”

“Oh, he wanted to go, and asked me if he could stay six weeks. He will be well taken care of there.”

“Oh,” said the man, “I am unhappy. It isn’t right. He should have said good-bye to me.” With that he began to eat, saying, “Marlene, why are you crying? Your brother will certainly come back.”

Then he said, “Wife, this food is delicious. Give me some more.” And the more he ate the more he wanted, and he said, “Give me some more. You two shall have none of it. It seems to me as if it were all mine.” And he ate and ate, throwing all the bones under the table, until he had finished it all.

Marlene went to her chest of drawers, took her best silk scarf from the bottom drawer, and gathered all the bones from beneath the table and tied them up in her silk scarf, then carried them outside the door, crying tears of blood.

She laid them down beneath the juniper tree on the green grass, and after she had put them there, she suddenly felt better and did not cry anymore.

Then the juniper tree began to move. The branches moved apart, then moved together again, just as if someone were rejoicing and clapping his hands. At the same time a mist seemed to rise from the tree, and in the center of this mist it burned like a fire, and a beautiful bird flew out of the fire singing magnificently, and it flew high into the air, and when it was gone, the juniper tree was just as it had been before, and the cloth with the bones was no longer there. Marlene, however, was as happy and contented as if her brother were still alive. And she went merrily into the house, sat down at the table, and ate.

Then the bird flew away and lit on a goldsmith’s house, and began to sing:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

The goldsmith was sitting in his workshop making a golden chain, when he heard the bird sitting on his roof and singing. The song seemed very beautiful to him. He stood up, but as he crossed the threshold he lost one of his slippers. However, he went right up the middle of the street with only one slipper and one sock on. He had his leather apron on, and in one hand he had a golden chain and in the other his tongs. The sun was shining brightly on the street.

He walked onward, then stood still and said to the bird, “Bird,” he said, “how beautifully you can sing. Sing that piece again for me.”

“No,” said the bird, “I do not sing twice for nothing. Give me the golden chain, and then I will sing it again for you.”

The goldsmith said, “Here is the golden chain for you. Now sing that song again for me.” Then the bird came and took the golden chain in his right claw, and went and sat in front of the goldsmith, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Then the bird flew away to a shoemaker, and lit on his roof and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Hearing this, the shoemaker ran out of doors in his shirtsleeves, and looked up at his roof, and had to hold his hand in front of his eyes to keep the sun from blinding him. “Bird,” said he, “how beautifully you can sing.”

Then he called in at his door, “Wife, come outside. There is a bird here. Look at this bird. He certainly can sing.” Then he called his daughter and her children, and the journeyman, and the apprentice, and the maid, and they all came out into the street and looked at the bird and saw how beautiful he was, and what fine red and green feathers he had, and how his neck was like pure gold, and how his eyes shone like stars in his head.

“Bird,” said the shoemaker, “now sing that song again for me.”

“No,” said the bird, “I do not sing twice for nothing. You must give me something.”

“Wife,” said the man, “go into the shop. There is a pair of red shoes on the top shelf. Bring them down.” Then the wife went and brought the shoes.

“There, bird,” said the man, “now sing that piece again for me.” Then the bird came and took the shoes in his left claw, and flew back to the roof, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

When he had finished his song he flew away. In his right claw he had the chain and in his left one the shoes. He flew far away to a mill, and the mill went clickety-clack, clickety-clack, clickety-clack. In the mill sat twenty miller’s apprentices cutting a stone, and chiseling chip-chop, chip-chop, chip-chop. And the mill went clickety-clack, clickety-clack, clickety-clack.

Then the bird went and sat on a linden tree which stood in front of the mill, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

Then one of them stopped working.

My father, he ate me,

Then two more stopped working and listened,

My sister Marlene,

Then four more stopped,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Now only eight only were chiseling,

Laid them beneath

Now only five,

the juniper tree,

Now only one,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Then the last one stopped also, and heard the last words. “Bird,” said he, “how beautifully you sing. Let me hear that too. Sing it once more for me.”

“No,” said the bird, “I do not sing twice for nothing. Give me the millstone, and then I will sing it again.”

“Yes,” he said, “if it belonged only to me, you should have it.”

“Yes,” said the others, “if he sings again he can have it.”

Then the bird came down, and the twenty millers took a beam and lifted the stone up. Yo-heave-ho! Yo-heave-ho! Yo-heave-ho!

The bird stuck his neck through the hole and put the stone on as if it were a collar, then flew to the tree again, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

When he was finished singing, he spread his wings, and in his right claw he had the chain, and in his left one the shoes, and around his neck the millstone. He flew far away to his father’s house.

In the room the father, the mother, and Marlene were sitting at the table.

The father said, “I feel so contented. I am so happy.”

“Not I,” said the mother, “I feel uneasy, just as if a bad storm were coming.”

But Marlene just sat and cried and cried.

Then the bird flew up, and as it seated itself on the roof, the father said, “Oh, I feel so truly happy, and the sun is shining so beautifully outside. I feel as if I were about to see some old acquaintance again.”

“Not I,” said the woman, “I am so afraid that my teeth are chattering, and I feel like I have fire in my veins.” And she tore open her bodice even more. Marlene sat in a corner crying. She held a handkerchief before her eyes and cried until it was wet clear through.

Then the bird seated itself on the juniper tree, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

The mother stopped her ears and shut her eyes, not wanting to see or hear, but there was a roaring in her ears like the fiercest storm, and her eyes burned and flashed like lightning.

My father, he ate me,

“Oh, mother,” said the man, “that is a beautiful bird. He is singing so splendidly, and the sun is shining so warmly, and it smells like pure cinnamon.”

My sister Marlene,

Then Marlene laid her head on her knees and cried and cried, but the man said, “I am going out. I must see the bird up close.”

“Oh, don’t go,” said the woman, “I feel as if the whole house were shaking and on fire.”

But the man went out and looked at the bird.

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

With this the bird dropped the golden chain, and it fell right around the man’s neck, so exactly around it that it fit beautifully. Then the man went in and said, “Just look what a beautiful bird that is, and what a beautiful golden chain he has given me, and how nice it looks.”

But the woman was terrified. She fell down on the floor in the room, and her cap fell off her head. Then the bird sang once more:

My mother killed me.

“I wish I were a thousand fathoms beneath the earth, so I would not have to hear that!”

My father, he ate me,

Then the woman fell down as if she were dead.

My sister Marlene,

“Oh,” said Marlene, “I too will go out and see if the bird will give me something.” Then she went out.

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

He threw the shoes down to her.

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Then she was contented and happy. She put on the new red shoes and danced and leaped into the house. “Oh,” she said, “I was so sad when I went out and now I am so contented. That is a splendid bird, he has given me a pair of red shoes.”

“No,” said the woman, jumping to her feet and with her hair standing up like flames of fire, “I feel as if the world were coming to an end. I too, will go out and see if it makes me feel better.”

And as she went out the door, crash! the bird threw the millstone on her head, and it crushed her to death.

The father and Marlene heard it and went out. Smoke, flames, and fire were rising from the place, and when that was over, the little brother was standing there, and he took his father and Marlene by the hand, and all three were very happy, and they went into the house, sat down at the table, and ate.

Story by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

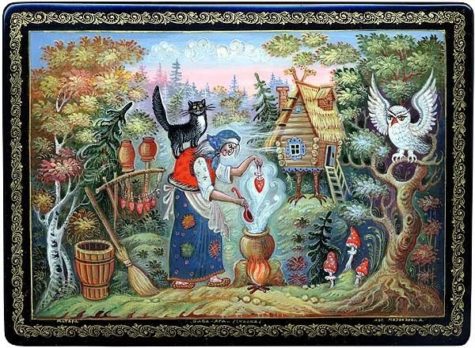

An Improved Baba Yaga Story

From Old Peter’s Russian Tales by Arthur Ransome we have an improved version of the fairy tale about Baba Yaga and the Little Girl.

“Tell us about Baba Yaga,” begged Maroosia.

“Yes,” said Vanya, “please, grandfather, and about the little hut on hen’s legs.”

“Baba Yaga is a witch,” said old Peter; “a terrible old woman she is, but sometimes kind enough. You know it was she who told Prince Ivan how to win one of the daughters of the Tzar of the Sea, and that was the best daughter of the bunch, Vasilissa the Very Wise. But then Baba Yaga is usually bad, as in the case of Vasilissa the Very Beautiful, who was only saved from her iron teeth by the cleverness of her Magic Doll.”

“Tell us the story of the Magic Doll,” begged Maroosia.

“I will some day,” said old Peter.

“And has Baba Yaga really got iron teeth?” asked Vanya.

“Iron, like the poker and tongs,” said old Peter.

“What for?” said Maroosia.

“To eat up little Russian children,” said old Peter, “when she can get them. She usually only eats bad ones, because the good ones get away. She is bony all over, and her eyes flash, and she drives about in a mortar, beating it with a pestle, and sweeping up her tracks with a besom, so that you cannot tell which way she has gone.”

“And her hut?” said Vanya. He had often heard about it before, but he wanted to hear about it again.

“She lives in a little hut which stands on hen’s legs. Sometimes it faces the forest, sometimes it faces the path, and sometimes it walks solemnly about. But in some of the stories she lives in another kind of hut, with a railing of tall sticks, and a skull on each stick. And all night long fire glows in the skulls and fades as the dawn rises.”

“Now tell us one of the Baba Yaga stories,” said Maroosia.

“Please,” said Vanya.

“I will tell you how one little girl got away from her, and then, if ever she catches you, you will know exactly what to do.”

And old Peter put down his pipe and began:—

Baba Yaga and the Little Girl with the Kind Heart

Once upon a time there was a widowed old man who lived alone in a hut with his little daughter. Very merry they were together, and they used to smile at each other over a table just piled with bread and jam. Everything went well, until the old man took it into his head to marry again.

Yes, the old man became foolish in the years of his old age, and he took another wife. And so the poor little girl had a stepmother. And after that everything changed. There was no more bread and jam on the table, and no more playing bo-peep, first this side of the samovar and then that, as she sat with her father at tea.

It was worse than that, for she never did sit at tea. The stepmother said that everything that went wrong was the little girl’s fault. And the old man believed his new wife, and so there were no more kind words for his little daughter. Day after day the stepmother used to say that the little girl was too naughty to sit at table. And then she would throw her a crust and tell her to get out of the hut and go and eat it somewhere else.

And the poor little girl used to go away by herself into the shed in the yard, and wet the dry crust with her tears, and eat it all alone. Ah me! she often wept for the old days, and she often wept at the thought of the days that were to come.

Mostly she wept because she was all alone, until one day she found a little friend in the shed. She was hunched up in a corner of the shed, eating her crust and crying bitterly, when she heard a little noise. It was like this: scratch—scratch. It was just that, a little gray mouse who lived in a hole.

Out he came, his little pointed nose and his long whiskers, his little round ears and his bright eyes. Out came his little humpy body and his long tail. And then he sat up on his hind legs, and curled his tail twice round himself and looked at the little girl.

The little girl, who had a kind heart, forgot all her sorrows, and took a scrap of her crust and threw it to the little mouse. The mouseykin nibbled and nibbled, and there, it was gone, and he was looking for another. She gave him another bit, and presently that was gone, and another and another, until there was no crust left for the little girl. Well, she didn’t mind that. You see, she was so happy seeing the little mouse nibbling and nibbling.

When the crust was done the mouseykin looks up at her with his little bright eyes, and “Thank you,” he says, in a little squeaky voice. “Thank you,” he says; “you are a kind little girl, and I am only a mouse, and I’ve eaten all your crust. But there is one thing I can do for you, and that is to tell you to take care. The old woman in the hut (and that was the cruel stepmother) is own sister to Baba Yaga, the bony-legged, the witch. So if ever she sends you on a message to your aunt, you come and tell me. For Baba Yaga would eat you soon enough with her iron teeth if you did not know what to do.”

“Oh, thank you,” said the little girl; and just then she heard the stepmother calling to her to come in and clean up the tea things, and tidy the house, and brush out the floor, and clean everybody’s boots.

So off she had to go.

When she went in she had a good look at her stepmother, and sure enough she had a long nose, and she was as bony as a fish with all the flesh picked off, and the little girl thought of Baba Yaga and shivered, though she did not feel so bad when she remembered the mouseykin out there in the shed in the yard.

The very next morning it happened. The old man went off to pay a visit to some friends of his in the next village, just as I go off sometimes to see old Fedor, God be with him. And as soon as the old man was out of sight the wicked stepmother called the little girl.

“You are to go to-day to your dear little aunt in the forest,” says she, “and ask her for a needle and thread to mend a shirt.”

“But here is a needle and thread,” says the little girl.

“Hold your tongue,” says the stepmother, and she gnashes her teeth, and they make a noise like clattering tongs. “Hold your tongue,” she says. “Didn’t I tell you you are to go to-day to your dear little aunt to ask for a needle and thread to mend a shirt?”

“How shall I find her?” says the little girl, nearly ready to cry, for she knew that her aunt was Baba Yaga, the bony-legged, the witch.

The stepmother took hold of the little girl’s nose and pinched it.

“That is your nose,” she says. “Can you feel it?”

“Yes,” says the poor little girl.

“You must go along the road into the forest till you come to a fallen tree; then you must turn to your left, and then follow your nose and you will find her,” says the stepmother. “Now, be off with you, lazy one. Here is some food for you to eat by the way.” She gave the little girl a bundle wrapped up in a towel.

The little girl wanted to go into the shed to tell the mouseykin she was going to Baba Yaga, and to ask what she should do. But she looked back, and there was the stepmother at the door watching her. So she had to go straight on.

She walked along the road through the forest till she came to the fallen tree. Then she turned to the left. Her nose was still hurting where the stepmother had pinched it, so she knew she had to go straight ahead. She was just setting out when she heard a little noise under the fallen tree. “Scratch—scratch.”

And out jumped the little mouse, and sat up in the road in front of her.

“O mouseykin, mouseykin,” says the little girl, “my stepmother has sent me to her sister. And that is Baba Yaga, the bony-legged, the witch, and I do not know what to do.”

“It will not be difficult,” says the little mouse, “because of your kind heart. Take all the things you find in the road, and do with them what you like. Then you will escape from Baba Yaga, and everything will be well.”

“Are you hungry, mouseykin?” said the little girl

“I could nibble, I think,” says the little mouse.

The little girl unfastened the towel, and there was nothing in it but stones. That was what the stepmother had given the little girl to eat by the way.

“Oh, I’m so sorry,” says the little girl. “There’s nothing for you to eat.”

“Isn’t there?” said mouseykin, and as she looked at them the little girl saw the stones turn to bread and jam. The little girl sat down on the fallen tree, and the little mouse sat beside her, and they ate bread and jam until they were not hungry any more.

“Keep the towel,” says the little mouse; “I think it will be useful. And remember what I said about the things you find on the way. And now good-bye,” says he.

“Good-bye,” says the little girl, and runs along.

As she was running along she found a nice new handkerchief lying in the road. She picked it up and took it with her. Then she found a little bottle of oil. She picked it up and took it with her. Then she found some scraps of meat.

“Perhaps I’d better take them too,” she said; and she took them.

Then she found a gay blue ribbon, and she took that. Then she found a little loaf of good bread, and she took that too.

“I daresay somebody will like it,” she said.

And then she came to the hut of Baba Yaga, the bony-legged, the witch. There was a high fence round it with big gates. When she pushed them open they squeaked miserably, as if it hurt them to move. The little girl was sorry for them.

“How lucky,” she says, “that I picked up the bottle of oil!” and she poured the oil into the hinges of the gates.

Inside the railing was Baba Yaga’s hut, and it stood on hen’s legs and walked about the yard. And in the yard there was standing Baba Yaga’s servant, and she was crying bitterly because of the tasks Baba Yaga set her to do. She was crying bitterly and wiping her eyes on her petticoat.

“How lucky,” says the little girl, “that I picked up a handkerchief!” And she gave the handkerchief to Baba Yaga’s servant, who wiped her eyes on it and smiled through her tears.

Close by the hut was a huge dog, very thin, gnawing a dry crust.

“How lucky,” says the little girl, “that I picked up a loaf!” And she gave the loaf to the dog, and he gobbled it up and licked his lips.

The little girl went bravely up to the hut and knocked on the door.

“Come in,” says Baba Yaga.

The little girl went in, and there was Baba Yaga, the bony-legged, the witch, sitting weaving at a loom. In a corner of the hut was a thin black cat watching a mouse-hole.

“Good-day to you, auntie,” says the little girl, trying not to tremble.

“Good-day to you, niece,” says Baba Yaga.

“My stepmother has sent me to you to ask for a needle and thread to mend a shirt.”

“Very well,” says Baba Yaga, smiling, and showing her iron teeth. “You sit down here at the loom, and go on with my weaving, while I go and get you the needle and thread.”

The little girl sat down at the loom and began to weave.

Baba Yaga went out and called to her servant, “Go, make the bath hot and scrub my niece. Scrub her clean. I’ll make a dainty meal of her.”

The servant came in for the jug. The little girl begged her, “Be not too quick in making the fire, and carry the water in a sieve.” The servant smiled, but said nothing, because she was afraid of Baba Yaga. But she took a very long time about getting the bath ready.

Baba Yaga came to the window and asked,—

“Are you weaving, little niece? Are you weaving, my pretty?”

“I am weaving, auntie,” says the little girl.

When Baba Yaga went away from the window, the little girl spoke to the thin black cat who was watching the mouse-hole.

“What are you doing, thin black cat?”

“Watching for a mouse,” says the thin black cat. “I haven’t had any dinner for three days.”

“How lucky,” says the little girl, “that I picked up the scraps of meat!” And she gave them to the thin black cat. The thin black cat gobbled them up, and said to the little girl,—

“Little girl, do you want to get out of this?”

“Catkin dear,” says the little girl, “I do want to get out of this, for Baba Yaga is going to eat me with her iron teeth.”

“Well,” says the cat, “I will help you.”

Just then Baba Yaga came to the window.

“Are you weaving, little niece?” she asked. “Are you weaving, my pretty?”

“I am weaving, auntie,” says the little girl, working away, while the loom went clickety clack, clickety clack.

Baba Yaga went away.

Says the thin black cat to the little girl: “You have a comb in your hair, and you have a towel. Take them and run for it while Baba Yaga is in the bath-house. When Baba Yaga chases after you, you must listen; and when she is close to you, throw away the towel, and it will turn into a big, wide river. It will take her a little time to get over that. But when she does, you must listen; and as soon as she is close to you throw away the comb, and it will sprout up into such a forest that she will never get through it at all.”

“But she’ll hear the loom stop,” says the little girl.

“I’ll see to that,” says the thin black cat.

The cat took the little girl’s place at the loom.

Clickety clack, clickety clack; the loom never stopped for a moment.

The little girl looked to see that Baba Yaga was in the bath-house, and then she jumped down from the little hut on hen’s legs, and ran to the gates as fast as her legs could flicker.

The big dog leapt up to tear her to pieces. Just as he was going to spring on her he saw who she was.

“Why, this is the little girl who gave me the loaf,” says he. “A good journey to you, little girl;” and he lay down again with his head between his paws.

When she came to the gates they opened quietly, quietly, without making any noise at all, because of the oil she had poured into their hinges.

Outside the gates there was a little birch tree that beat her in the eyes so that she could not go by.

“How lucky,” says the little girl, “that I picked up the ribbon!” And she tied up the birch tree with the pretty blue ribbon. And the birch tree was so pleased with the ribbon that it stood still, admiring itself, and let the little girl go by.

How she did run!

Meanwhile the thin black cat sat at the loom. Clickety clack, clickety clack, sang the loom; but you never saw such a tangle as the tangle made by the thin black cat.

And presently Baba Yaga came to the window.

“Are you weaving, little niece?” she asked. “Are you weaving, my pretty?”

“I am weaving, auntie,” says the thin black cat, tangling and tangling, while the loom went clickety clack, clickety clack.

“That’s not the voice of my little dinner,” says Baba Yaga, and she jumped into the hut, gnashing her iron teeth; and there was no little girl, but only the thin black cat, sitting at the loom, tangling and tangling the threads.

“Grr,” says Baba Yaga, and jumps for the cat, and begins banging it about. “Why didn’t you tear the little girl’s eyes out?”

“In all the years I have served you,” says the cat, “you have only given me one little bone; but the kind little girl gave me scraps of meat.”

Baba Yaga threw the cat into a corner, and went out into the yard.

“Why didn’t you squeak when she opened you?” she asked the gates.

“Why didn’t you tear her to pieces?” she asked the dog.

“Why didn’t you beat her in the face, and not let her go by?” she asked the birch tree.

“Why were you so long in getting the bath ready? If you had been quicker, she never would have got away,” said Baba Yaga to the servant.

And she rushed about the yard, beating them all, and scolding at the top of her voice.

Ah!” said the gates, “in all the years we have served you, you never even eased us with water; but the kind little girl poured good oil into our hinges.”

“Ah!” said the dog, “in all the years I’ve served you, you never threw me anything but burnt crusts; but the kind little girl gave me a good loaf.”

“Ah!” said the little birch tree, “in all the years I’ve served you, you never tied me up, even with thread; but the kind little girl tied me up with a gay blue ribbon.”

“Ah!” said the servant, “in all the years I’ve served you, you have never given me even a rag; but the kind little girl gave me a pretty handkerchief.”

Baba Yaga gnashed at them with her iron teeth. Then she jumped into the mortar and sat down. She drove it along with the pestle, and swept up her tracks with a besom, and flew off in pursuit of the little girl.

The little girl ran and ran. She put her ear to the ground and listened. Bang, bang, bangety bang! she could hear Baba Yaga beating the mortar with the pestle. Baba Yaga was quite close. There she was, beating with the pestle and sweeping with the besom, coming along the road.

There she was, beating with the pestle and sweeping with the besom.

As quickly as she could, the little girl took out the towel and threw it on the ground. And the towel grew bigger and bigger, and wetter and wetter, and there was a deep, broad river between Baba Yaga and the little girl.

The little girl turned and ran on. How she ran!

Baba Yaga came flying up in the mortar. But the mortar could not float in the river with Baba Yaga inside. She drove it in, but only got wet for her trouble. Tongs and pokers tumbling down a chimney are nothing to the noise she made as she gnashed her iron teeth. She turned home, and went flying back to the little hut on hen’s legs. Then she got together all her cattle and drove them to the river.

“Drink, drink!” she screamed at them; and the cattle drank up all the river to the last drop. And Baba Yaga, sitting in the mortar, drove it with the pestle, and swept up her tracks with the besom, and flew over the dry bed of the river and on in pursuit of the little girl.

The little girl put her ear to the ground and listened. Bang, bang, bangety bang! She could hear Baba Yaga beating the mortar with the pestle. Nearer and nearer came the noise, and there was Baba Yaga, beating with the pestle and sweeping with the besom, coming along the road close behind.

The little girl threw down the comb, and grew bigger and bigger, and its teeth sprouted up into a thick forest, thicker than this forest where we live—so thick that not even Baba Yaga could force her way through. And Baba Yaga, gnashing her teeth and screaming with rage and disappointment, turned round and drove away home to her little hut on hen’s legs.

The little girl ran on home. She was afraid to go in and see her stepmother, so she ran into the shed.

Scratch, scratch! Out came the little mouse.

“So you got away all right, my dear,” says the little mouse. “Now run in. Don’t be afraid. Your father is back, and you must tell him all about it.”

The little girl went into the house.

“Where have you been?” says her father; “and why are you so out of breath?”

The stepmother turned yellow when she saw her, and her eyes glowed, and her teeth ground together until they broke.

But the little girl was not afraid, and she went to her father and climbed on his knee, and told him everything just as it had happened. And when the old man knew that the stepmother had sent his little daughter to be eaten by Baba Yaga, he was so angry that he drove her out of the hut, and ever afterwards lived alone with the little girl. Much better it was for both of them.

“And the little mouse?” said Ivan.

“The little mouse,” said old Peter, “came and lived in the hut, and every day it used to sit up on the table and eat crumbs, and warm its paws on the little girl’s glass of tea.”

Baba Yaga and the Little Girl

Baba Yaga lived deep in the forest and scared passersby to death just by appearing to them. She then devoured Her victims, which is why Her picket fence was topped with skulls. Children’s stories about Baba Yaga tend to be quite similar. Here is a story about a little girl, her wicked stepmother, and Baba Yaga.

Once upon a time there was a man and woman who had an only daughter. When his wife died, the man took another. But the wicked stepmother took a dislike to the girl, beat her hard and wondered how to be rid of her forever. One day the father went off somewhere and the stepmother said to the girl, “Go to your aunt, to my sister, and ask her for a needle and thread to sew you a blouse.” The aunt was really Baba Yaga, the bony witch.

Now, the little girl was not stupid and she first went to her own aunt for advice. “Good morrow. Auntie,” she said. “Mother has sent me to her sister for a needle and thread to sew me a blouse. What should I do?”

The aunt told her what to do. “My dear niece,” she said. “You will find a birch-tree there that will lash your face; you must tie it with a ribbon. You will find gates that will creak and bang; you must pour oil on the hinges. You will find dogs that will try to rip you apart; you must throw them fresh rolls. You will find a cat that will try to scratch your eyes out; you must give her some ham.”

The little girl went off, walked and walked and finally came to the witch’s abode.

There stood a hut, and inside sat Baba Yaga, the bony witch, spinning. “Good day. Auntie,” said the little girl.

“Good day, dearie,” the witch replied.

“Mother sent me for a needle and thread to sew me a blouse,” said the girl.

“Very well,” Baba Yaga said. “Sit down and weave.”

The girl sat at the loom. then Baba Yaga went out and told her serving-maid, “Go and heat up the bath-house and give my niece a good wash; I want to eat her for breakfast.”

The serving-maid did as she was bid; and the poor little girl sat there half dead with fright, begging, “Oh, please, dear serving-maid, don’t bum the wood, pour water on instead, and carry the water in a sieve.” And she gave the maid a kerchief.

Meanwhile Baba Yaga was waiting; she went to the window and asked, “Are you weaving, dear niece? Are you weaving, my dear?”

“I’m weaving, Auntie,” the girl replied, “I’m weaving, my dear.”

When Baba Yaga moved away from the window, the little girl gave some ham to the cat and asked her whether there was any escape. At once the cat replied, “Here is a comb and towel. Take them and run away. Baba Yaga will chase you; put your ear to the ground and, when you hear her coming, throw down the towel?and a wide, wide river will appear. And if she crosses the river and starts to catch you up, put your ear to the ground again and, when you hear her coming close, throw down your comb and a dense forest will appear. She won’t be able to get through that.”

The little girl took the towel and comb and ran. As she ran from the house, the dogs tried to tear her to pieces, but she tossed them the fresh rolls and they let her pass. The gates tried to bang shut, but she poured some oil on the hinges, and they let her through. The birch-tree tried to lash her face, but she tied it with a ribbon, and it let her pass.

In the meantime, the cat sat down at the loom to weave?though, truth to tell, she tangled it all up instead. Now and then Baba Yaga would come to the window and call, “Are you weaving, dear niece? Are you weaving, my dear?” And the cat would answer in a low voice, “I’m weaving. Auntie. I’m weaving, my dear.”

The witch rushed into the hut and saw that the girl was gone. She gave the cat a good beating and scolded her for not scratching out the girl’s eyes. But the cat answered her, “I’ve served you for years, yet you’ve never even given me a bone, but she gave me some ham.”

Baba Yaga then turned on the dogs, the gates, the birch-tree and the serving-maid, and set to thrashing and scolding them all. But the dogs said to her, “We’ve served you for years, yet you’ve never even thrown us a burnt crust, but she gave us fresh rolls.”

And the gates said, “We’ve served you for years, yet you’ve never even poured water on our hinges, but she oiled them for us.”

And the birch-tree said, “I’ve served you for years, yet you’ve never even tied me up with thread, but she tied me with a ribbon.” And the serving-maid said, “I’ve served you for years, yet you’ve never even given me a rag, but she gave me a kerchief.”

From: Russian Fairy Tales

James Cheney: Invocation To The Dark Mother

Daniel: Prayer Before The Final Battle

blessed obyno: Queen of Ghosts

blessed obyno: Queen of Ghosts

Caerlion Arthur: The Great, Bloody and Bruised Veil of the World