Fairy Tales and Stories

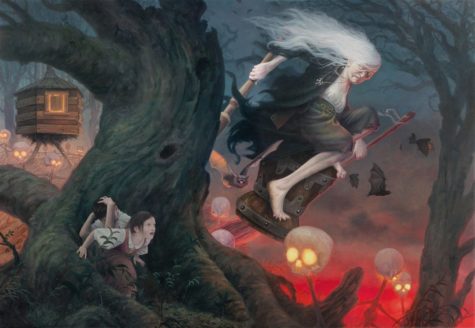

Baba Yaga and the Twins

Somewhere, I cannot tell you exactly where, but certainly in vast Russia, there lived a peasant with his wife and they had twins — a son and daughter. One day the wife died and the husband mourned over her very sincerely for a long time. One year passed, and two years, and even longer. But there is no order in a house without a woman, and a day came when the man thought, “If I marry again possibly it would turn out all right.” And so he did, and had children by his second wife.

The stepmother was envious of the stepson and daughter and began to use them hardly. She scolded them without any reason, sent them away from home as often as she wished, and gave them scarcely enough to eat. Finally she wanted to get rid of them altogether. Do you know what it means to allow a wicked thought to enter one’s heart?

The wicked thought grows all the time like a poisonous plant and slowly kills the good thoughts. A wicked feeling was growing in the stepmother’s heart, and she determined to send the children to the witch, thinking sure enough that they would never return.

“Dear children,” she said to the orphans, “go to my grandmother who lives in the forest in a hut on hen’s feet. You will do everything she wants you to, and she will give you sweet things to eat and you will be happy.”

The orphans started out. But instead of going to the witch, the sister, a bright little girl, took her brother by the hand and ran to their own old, old grandmother and told her all about their going to the forest.

“Oh, my poor darlings!” said the good old grandmother, pitying the children, “my heart aches for you, but it is not in my power to help you. You have to go not to a loving grandmother, but to a wicked witch. Now listen to me, my darlings,” she continued; “I will give you a hint: Be kind and good to every one; do not speak ill words to any one; do not despise helping the weakest, and always hope that for you, too, there will be the needed help.”

The good old grandmother gave the children some delicious fresh milk to drink and to each a big slice of ham. She also gave them some cookies—there are cookies everywhere—and when the children departed she stood looking after them a long, long time.

The obedient children arrived at the forest and, oh, wonder! there stood a hut, and what a curious one! It stood on tiny hen’s feet, and at the top was a rooster’s head. With their shrill, childish voices they called out loud: “Izboushka, Izboushka! turn thy back to the forest and thy front to us!”

The hut did as they commanded. The two orphans looked inside and saw the witch resting there, her head near the threshold, one foot in one corner, the other foot in another corner, and her knees quite close to the ridge pole.

“Fou, Fou, Fou!” exclaimed the witch; “I feel the Russian spirit.”

The children were afraid, and stood close, very close together, but in spite of their fear they said very politely: “Ho, grandmother, our stepmother sent us to thee to serve thee.”

“All right; I am not opposed to keeping you, children. If you satisfy all my wishes I shall reward you; if not, I shall eat you up.”

Without any delay the witch ordered the girl to spin the thread, and the boy, her brother, to carry water in a sieve to fill a big tub. The poor orphan girl wept at her spinning-wheel and wiped away her bitter tears. At once all around her appeared small mice squeaking and saying:

“Sweet girl, do not cry. Give us cookies and we will help thee.”

The little girl willingly did so.

“Now,”gratefully squeaked the mice, “go and find the black cat. He is very hungry; give him a slice of ham and he will help thee.”

The girl speedily went in search of the cat and saw her brother in great distress about the tub, so many times he had filled the sieve, yet the tub was still dry. The little birds passed, flying near by, and chirped to the children:

“Kind-hearted little children, give us some crumbs and we will advise you.”

The orphans gave the birds some crumbs and the grateful birds chirped again: “Some clay and water, children dear!”

Then away they flew through the air.

The children understood the hint, spat in the sieve, plastered it up with clay and rilled the tub in a very short time. Then they both returned to the hut and on the threshold met the black cat. They generously gave him some of the good ham which their good grandmother had given them, petted him and asked: “Dear Kitty-cat, black and pretty, tell us what to do in order to get away from thy mistress, the witch?”

“Well,” very seriously answered the cat, “I will give you a towel and a comb and then you must run away. When you hear the witch running after you, drop the towel behind your back and a large river will appear in place of the towel.

If you hear her once more, throw down the comb and in place of the comb there will appear a dark wood. This wood will protect you from the wicked witch, my mistress.”

Baba Yaga came home just then.

“Is it not wonderful?” she thought; “everything is exactly right.”

“Well,” she said to the children, “today you were brave and smart; let us see to-morrow. Your work will be more difficult and I hope I shall eat you up.”

The poor orphans went to bed, not to a warm bed prepared by loving hands, but on the straw in a cold corner. Nearly scared to death from fear, they lay there, afraid to talk, afraid even to breathe. The next morning the witch ordered all the linen to be woven and a large supply of firewood to be brought from the forest.

The children took the towel and comb and ran away as fast as their feet could possibly carry them. The dogs were after them, but they threw them the cookies that were left; the gates did not open themselves, but the children smoothed them with oil; the birch tree near the path almost scratched their eyes out, but the gentle girl fastened a pretty ribbon to it. So they went farther and farther and ran out of the dark forest into the wide, sunny fields.

The cat sat down by the loom and tore the thread to pieces, doing it with delight. Baba Yaga returned.

“Where are the children?” she shouted, and began to beat the cat. “Why hast thou let them go, thou treacherous cat? Why hast thou not scratched their faces?”

The cat answered: “Well, it was because I have served thee so many years and thou hast never given me a bite, while the dear children gave me some good ham.”

The witch scolded the dogs, the gates, and the birch tree near the path.

“Well,” barked the dogs, “thou certainly art our mistress, but thou hast never done us a favor, and the orphans were kind to us.”

The gates replied: “We were always ready to obey thee, but thou didst neglect us, and the dear children smoothed us with oil.”

“The children ran away as fast as their feet could possibly carry them.”

The birch tree lisped with its leaves, “Thou hast never put a simple thread over my branches and the little darlings adorned them with a pretty ribbon.”

Baba Yaga understood that there was no help and started to follow the children herself. In her great hurry she forgot to look for the towel and the comb, but jumped astride a broom and was off. The children heard her coming and threw the towel behind them. At once a river, wide and blue, appeared and watered the field. Baba Yaga hopped along the shore until she finally found a shallow place and crossed it.

Again the children heard her hurry after them and so they threw down the comb. This time a forest appeared, a dark and dusky forest in which the roots were interwoven, the branches matted together, and the tree-tops touching each other. The witch tried very hard to pass through, but in vain, and so, very, very angry, she returned home.

The orphans rushed to their father, told him all about their great distress, and thus concluded their pitiful story: “Ah, father dear, why dost thou love us less than our brothers and sisters?”

The father was touched and became angry. He sent the wicked stepmother away and lived a new life with his good children. From that time he watched over their happiness and never neglected them any more.

How do I know this story is true? Why, one was there who told me about it.

From:

Folk Tales From the Russian, by Verra Xenophontovna Kalamatiano de Blumenthal, (1903)

The Creation of The Moon

The man cut his throat and left his head there.

The others went to get it.

When they got there they put the head in a sack.

Farther on the head fell out onto the ground.

They put the head back in the sack.

Farther on the head fell out again.

Around the first sack they put a second one that

was thicker.

But the head fell out just the same.

It should be explained that they were taking the head

to show to the others.

They did not put the head back in the sack.

They left it in the middle of the road.

They went away.

They crossed the river.

But the head followed them.

They climbed up a tree full of fruit

to see whether it would go past.

The head stopped at the foot of the tree

and asked them for some fruit.

So the men shook the tree.

The head went to get the fruit.

Then it asked for some more.

So the men shook the tree

so that the fruit fell into the water.

The head said it couldn’t get the fruit from there.

So the men threw the fruit a long way

to make the head go a long way to get it so they could go.

While the head was getting the fruit

the men got down from the tree and went on.

The head came back and looked at the tree

and didn’t see anybody

so went on rolling down the road.

The men had stopped to wait

to see whether the head would follow them.

They saw the head come rolling.

They ran.

They got to their hut they told the others that the head

was rolling after them and to shut the door.

All the huts were closed tight.

When it got there the head commanded them to open the doors.

The owners would not open them because they were afraid.

So the head started to think what it would turn into.

If it turned into water they would drink it.

If it turned into earth they would walk on it.

If it turned into a house they would live in it.

If it turned into a steer they would kill it and eat it.

If it turned into a cow they would milk it.

If it turned into a bean they would cook it.

If it turned into the sun

When men were cold it would heat them.

If it turned into rain the grass would grow and the

animals would crop it.

So it thought, and it said, “I will turn into the moon.”

It called, “Open the doors, I want to get my things.”

They would not open them.

The head cried. It called out, “At least give me

my two balls of twine.”

They threw out the two balls of twine through a hole.

It took them and threw them into the sky.

It asked them to throw it a little stick too

to roll the thread around so it could climb up.

Then it said, “I can climb, I am going to the sky.”

It started to climb.

The men opened the doors right away.

The head went on climbing.

The men shouted, “You going to the sky, head?”

It didn’t answer.

As soon as it got to the Sun

it turned into the Moon.

Toward evening the Moon was white, it was beautiful.

And the men were surprised

to see that the head had turned into the Moon.

~Anonymous

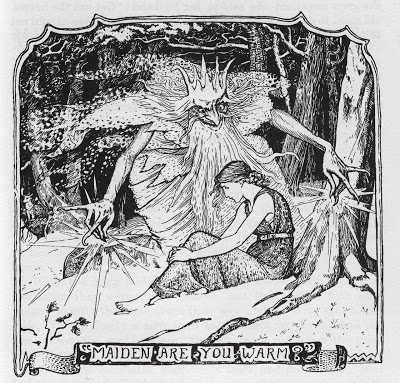

The Story of King Frost

There was once upon a time a peasant-woman who had a daughter and a step-daughter. The daughter had her own way in everything, and whatever she did was right in her mother’s eyes; but the poor step-daughter had a hard time. Let her do what she would, she was always blamed, and got small thanks for all the trouble she took; nothing was right, everything wrong; and yet, if the truth were known, the girl was worth her weight in gold–she was so unselfish and good-hearted.

But her step-mother did not like her, and the poor girl’s days were spent in weeping; for it was impossible to live peacefully with the woman. The wicked shrew was determined to get rid of the girl by fair means or foul, and kept saying to her father: ‘Send her away, old man; send her away–anywhere so that my eyes sha’n’t be plagued any longer by the sight of her, or my ears tormented by the sound of her voice. Send her out into the fields, and let the cutting frost do for her.’

In vain did the poor old father weep and implore her pity; she was firm, and he dared not gainsay her. So he placed his daughter in a sledge, not even daring to give her a horse-cloth to keep herself warm with, and drove her out on to the bare, open fields, where he kissed her and left her, driving home as fast as he could, that he might not witness her miserable death.

Deserted by her father, the poor girl sat down under a fir-tree at the edge of the forest and began to weep silently. Suddenly she heard a faint sound: it was King Frost springing from tree to tree, and cracking his fingers as he went. At length he reached the fir-tree beneath which she was sitting, and with a crisp crackling sound he alighted beside her, and looked at her lovely face.

‘Well, maiden,’ he snapped out, ‘do you know who I am? I am King Frost, king of the red-noses.’

‘All hail to you, great King!’ answered the girl, in a gentle, trembling voice. ‘Have you come to take me?’

‘Are you warm, maiden?’ he replied.

‘Quite warm, King Frost,’ she answered, though she shivered as she spoke.

Then King Frost stooped down, and bent over the girl, and the crackling sound grew louder, and the air seemed to be full of knives and darts; and again he asked:

‘Maiden, are you warm? Are you warm, you beautiful girl?’

And though her breath was almost frozen on her lips, she whispered gently, ‘Quite warm, King Frost.’

Then King Frost gnashed his teeth, and cracked his fingers, and his eyes sparkled, and the crackling, crisp sound was louder than ever, and for the last time he asked her:

‘Maiden, are you still warm? Are you still warm, little love?’

And the poor girl was so stiff and numb that she could just gasp, ‘Still warm, O King!’

Now her gentle, courteous words and her uncomplaining ways touched King Frost, and he had pity on her, and he wrapped her up in furs, and covered her with blankets, and he fetched a great box, in which were beautiful jewels and a rich robe embroidered in gold and silver. And she put it on, and looked more lovely than ever, and King Frost stepped with her into his sledge, with six white horses.

In the meantime the wicked step-mother was waiting at home for news of the girl’s death, and preparing pancakes for the funeral feast. And she said to her husband: ‘Old man, you had better go out into the fields and find your daughter’s body and bury her.’ Just as the old man was leaving the house the little dog under the table began to bark, saying:

‘YOUR daughter shall live to be your delight; HER daughter shall die this very night.’

‘Hold your tongue, you foolish beast!’ scolded the woman. ‘There’s a pancake for you, but you must say: “HER daughter shall have much silver and gold; HIS daughter is frozen quite stiff and cold.” ‘

But the doggie ate up the pancake and barked, saying: ‘His daughter shall wear a crown on her head; Her daughter shall die unwooed, unwed.’

Then the old woman tried to coax the doggie with more pancakes and to terrify it with blows, but he barked on, always repeating the same words. And suddenly the door creaked and flew open, and a great heavy chest was pushed in, and behind it came the step-daughter, radiant and beautiful, in a dress all glittering with silver and gold.

For a moment the step-mother’s eyes were dazzled. Then she called to her husband: ‘Old man, yoke the horses at once into the sledge, and take my daughter to the same field and leave her on the same spot exactly; ‘and so the old man took the girl and left her beneath the same tree where he had parted from his daughter. In a few minutes King Frost came past, and, looking at the girl, he said:

‘Are you warm, maiden?’

‘What a blind old fool you must be to ask such a question!’ she answered angrily. ‘Can’t you see that my hands and feet are nearly frozen?’

Then King Frost sprang to and fro in front of her, questioning her, and getting only rude, rough words in reply, till at last he got very angry, and cracked his fingers, and gnashed his teeth, and froze her to death.

But in the hut her mother was waiting for her return, and as she grew impatient she said to her husband: ‘Get out the horses, old man, to go and fetch her home; but see that you are careful not to upset the sledge and lose the chest.’

But the doggie beneath the table began to bark, saying: ‘Your daughter is frozen quite stiff and cold, And shall never have a chest full of gold.’

‘Don’t tell such wicked lies!’ scolded the woman. ‘There’s a cake for you; now say: “HER daughter shall marry a mighty King.”

At that moment the door flew open, and she rushed out to meet her daughter, and as she took her frozen body in her arms she too was chilled to death.

Story by Andrew Lang from The Yellow Fairy Book

The King of the Cats

Here’s a great cat story from Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland, by Lady Francesca Speranza Wilde, published in 1887.

A most important personage in feline history is the King of the Cats. He may be in your house a common looking fellow enough, with no distinguishing mark of exalted rank about him, so that it is very difficult to verify his genuine claims to royalty. Therefore the best way is to cut off a tiny little bit of his ear. If he is really the royal personage, he will immediately speak out and declare who he is; and perhaps, at the same the, tell you some very disagreeable truths about yourself, not at all pleasant to have discussed by the house cat.

A man once, in a fit of passion, cut off the head of the domestic pussy, and threw it on the fire. On which the head exclaimed, in a fierce voice, “Go tell your wife that you have cut off the head of the King of the Cats; but wait! I shall come back and be avenged for this insult,” and the eyes of the cat glared at him horribly from the fire.

And so it happened; for that day year, while the master of the house was playing with a pet kitten, it suddenly flew at his throat and bit him so severely that he died soon after.

A story is current also, that one night an old woman was sitting up very late spinning, when a knocking came to the door. “Who is there?” she asked. No answer; but still the knocking went on. “‘Who is there?” she asked a second the. No answer; and the knocking continued. “Who is there?” she asked the third time, in a very angry passion.

Then there came a small voice–“Ah, Judy, agrah, let me in,–for I am cold and hungry; open the door, Judy, agrah, and let me sit by the fire, for the night is cold out here. Judy, agrah, let me in, let me in!”

The heart of Judy was touched, for she thought it was some small child that had lost its way, and she rose up from her spinning, and went and opened the door–when in walked a large black cat with a white breast, and two white kittens after her.

They all made over to the fire and began to warm and dry themselves, purring all the time very loudly; but Judy said never a word, only went on spinning.

Then the black cat spoke at last–“Judy, agrah, don’t stay up so late again, for the fairies wanted to hold a council here tonight, and to have some supper, but you have prevented them; so they were very angry and determined to kill you, and only for myself and my two daughters here you would be dead by this time. So take my advice, don’t interfere with the fairy hours again, for the night is theirs, and they hate to look on the face of a mortal when they are out for pleasure or business. So I ran on to tell you, and now give me a drink of milk, for I must be off.”

And after the milk was finished the cat stood up, and called her daughters to come away.

“Good-night, Judy, agrah,” she said. “You have been very civil to me, and I’ll not forget it to you. Good-night, good night.”

With that the black cat and the two kittens whisked up the chimney; but Judy looking down saw something glittering on the hearth, and taking it up she found it was a piece of silver, more than she ever could make in a month by her spinning, and she was glad in her heart, and never again sat up so late to interfere with the fairy hours, but the black cat and her daughters came no more again to the house.

Kwan Yin and the Swallows

“Kwan Yin is one of the most universally beloved of deities in the Buddhist tradition. Also known as Kuan Yin, Quan Yin, Quan’Am (Vietnam), Kannon (Japan), and Kanin (Bali), She is the embodiment of compassionate loving kindness. As the Bodhisattva of Compassion, She hears the cries of all beings.”

Kwan Yin and the Swallows

by Dharmadasa Karuna

The cloud blue crests of Jianshan Mountain leaned into the morning light. Flaxen rays reached into the window of a young woman sleeping on a bed of straw. Her hair was the color of the night sky, and lapped over her belly and hips. Her skin was the color of the sun. She awoke and walked outside. The nest of swallows on her windowsill was empty. It was the end of summer.

Her bare feet pressed into the fallen leaves on the ground. She entered the woods in search of a cluster of white flowers with purple stems. Mother seemed unsure of herself this week, and Dong Quai would calm her nerves. She closed her eyes and let the forest guide her. She found the flowers in the silence.

“Kwan Yin, where are you? Talking to your birds again?”

“Coming mother.” The young woman emerged from the woods. “I was gathering a tonic for our tea.”

“I have to go wash clothes at the river for Mrs. Lim. Save the tea for lunch. We’re having visitors.”

“Who mother?”

“Madam Hong and her son.”

“Why are they coming? We don’t need visitors.”

“The fortune teller said you were a good match for Madam Hong’s son.”

“Mother, you know I don’t want to marry.”

“You are a woman now, and while your hair still falls down your back and your breath is sweet, you must take a husband.”

“I’m going to enter the nunnery.”

“That is a child’s dream, Kwan Yin.”

Kwan Yin looked down and did not answer.

“We are poor Kwan Yin, and the Hongs are wealthy. They are an honorable family. Do you understand?”

“Mother, I…”

“You have never been with a man and….”

“I know it is my duty to care for you.”

“They are not all as kind as your father was. After you clean the house and cook the meals, they will make you cut wood, carry water, and milk the goat. Then you must lay with them every night. Your work is only done when you sleep.”

“Mother, I know. I know what I must do.”

Crow Moon

Here’s the story line posted with the video:

An animated short created in my spare room! A flock of roosting crows, black as night themselves, are threatened by the advancing shadows at dusk. They need light for protection so with the help of the Raven Chief they take a piece of the sun and use it to save themselves from the darkness.

Found on: YouTube

The Legend of Pancake Marion

There’s been a lot of talk of late about Pancake Marion, and the whole “Shrove Tuesday” phenomenon. But just who is she? And why did she do the horrible things that she did? Historian Marcus Ploughmans looks back at the history of one of England’s darkest secrets.

“Pancake Marion, Pancake Marion

Now’s the time to fry them

Pancake Marion, Pancake Marion

Now’s the time to fry

Don’t you dare to drop them

On the table plop them

Tuesday’s day is pancake day

We dance our cares away”

The ever-popular children’s nursery rhyme is now only ever really associated with cooking pancakes. But there was once a time when it was sung to remind children of the dangers of going into the darkness of Marionwood, Herefordshire.

The Raven-Barrow Family Portrait

In 1854, Jonathon Raven-Barrow (a wealthy industrialist from Westminster, London) lost his entire fortune to bad investments made in overseas property. Jonathon, his wife and their daughter, Marion, were homeless and destitute. They were forced to live in makeshift accommodation in the woodlands of Hereford, surviving by eating scraps, scavenged from the dustbins of the local townsfolk.

But, unknown to the Raven-Barrows, the villagers had grown tired of the rogue family’s presence. They saw the family as vermin. The woods were once a play area for children, but had become a no-go area since the Raven-Barrows had taken over. The villagers conspired to trap the family, and, on the night of the 14th of February 1857, caught them deep within the woods.

One by one, they were boiled alive in a vat of rancid eggs and lard…ingredients that were consistently stolen. As Marion was being executed she managed to escape. The villagers assumed that her fierce wounds would finish her off. But they were wrong. She lived. Albeit deformed and unhinged. Her mind twisted by the sight of the murder of her parents.

She fed off wild animals…to begin with! When the animals ran out…she turned to the children of the village. And anyone else who was foolish enough to go into the woods. All were captured…tortured and eaten alive, covered in boiling batter. They called her Pancake Marion.

Armies of men would march into the woods, all carrying weapons…but none would return. In a five year period she claimed over 200 victims. Eventually, the woods were burned to the ground. It seemed the only way to end her reign of terror. And the name of Pancake Marion became a thing of folklore.

Source: Wikipedia

The Dryad

Here is a story about a Dryad by Hans Christian Anderson.

We are travelling to Paris to the Exhibition. Now we are there. That was a journey, a flight without magic. We flew on the wings of steam over the sea and across the land. Yes, our time is the time of fairy tales.

We are in the midst of Paris, in a great hotel. Blooming flowers ornament the staircases, and soft carpets the floors.

Our room is a very cozy one, and through the open balcony door we have a view of a great square. Spring lives down there; it has come to Paris, and arrived at the same time with us. It has come in the shape of a glorious young chestnut tree, with delicate leaves newly opened. How the tree gleams, dressed in its spring garb, before all the other trees in the place! One of these latter had been struck out of the list of living trees. It lies on the ground with roots exposed. On the place where it stood, the young chestnut tree is to be planted, and to flourish.

It still stands towering aloft on the heavy wagon which has brought it this morning a distance of several miles to Paris. For years it had stood there, in the protection of a mighty oak tree, under which the old venerable clergyman had often sat, with children listening to his stories.

The young chestnut tree had also listened to the stories; for the Dryad who lived in it was a child also. She remembered the time when the tree was so little that it only projected a short way above the grass and ferns around. These were as tall as they would ever be; but the tree grew every year, and enjoyed the air and the sunshine, and drank the dew and the rain. Several times it was also, as it must be, well shaken by the wind and the rain; for that is a part of education.

The Dryad rejoiced in her life, and rejoiced in the sunshine, and the singing of the birds; but she was most rejoiced at human voices; she understood the language of men as well as she understood that of animals.

Butterflies, cockchafers, dragon-flies, everything that could fly came to pay a visit. They could all talk. They told of the village, of the vineyard, of the forest, of the old castle with its parks and canals and ponds. Down in the water dwelt also living beings, which, in their way, could fly under the water from one place to another—beings with knowledge and delineation. They said nothing at all; they were so clever!

And the swallow, who had dived, told about the pretty little goldfish, of the thick turbot, the fat brill, and the old carp. The swallow could describe all that very well, but, “Self is the man,” she said. “One ought to see these things one’s self.” But how was the Dryad ever to see such beings? She was obliged to be satisfied with being able to look over the beautiful country and see the busy industry of men.

It was glorious; but most glorious of all when the old clergyman sat under the oak tree and talked of France, and of the great deeds of her sons and daughters, whose names will be mentioned with admiration through all time.

Then the Dryad heard of the shepherd girl, Joan of Arc, and of Charlotte Corday; she heard about Henry the Fourth, and Napoleon the First; she heard names whose echo sounds in the hearts of the people.

The village children listened attentively, and the Dryad no less attentively; she became a school-child with the rest. In the clouds that went sailing by she saw, picture by picture, everything that she heard talked about. The cloudy sky was her picture-book.

She felt so happy in beautiful France, the fruitful land of genius, with the crater of freedom. But in her heart the sting remained that the bird, that every animal that could fly, was much better off than she. Even the fly could look about more in the world, far beyond the Dryad’s horizon.

France was so great and so glorious, but she could only look across a little piece of it. The land stretched out, world-wide, with vineyards, forests and great cities. Of all these Paris was the most splendid and the mightiest. The birds could get there; but she, never!

Among the village children was a little ragged, poor girl, but a pretty one to look at. She was always laughing or singing and twining red flowers in her black hair.

“Don’t go to Paris!” the old clergyman warned her. “Poor child! if you go there, it will be your ruin.”

But she went for all that. Continue reading

Snowflake

Snowflake is a Slavonic story from Andrew Lang’s The Pink Fairy Book, published in 1897. This Russian folktale is closely associated with the Russian Christmas which is traditionally celebrated on Jan 6, and also with St John’s Day celebrated on June 24.

Once upon a time there lived a peasant called Ivan, and he had a wife whose name was Marie. They would have been quite happy except for one thing: they had no children to play with, and as they were now old people they did not find that watching the children of their neighbours at all made up to them for having one of their own.

One winter, which nobody living will ever forget, the snow lay so deep that it came up to the knees of even the tallest man. When it had all fallen, and the sun was shining again, the children ran out into the street to play, and the old man and his wife sat at their window and gazed at them. The children first made a sort of little terrace, and stamped it hard and firm, and then they began to make a snow woman. Ivan and Marie watched them, the while thinking about many things.

Suddenly Ivan’s face brightened, and, looking at his wife, he said, ‘Wife, why shouldn’t we make a snow woman too?’

‘Why not?’ replied Marie, who happened to be in a very good temper; ‘it might amuse us a little. But there is no use making a woman. Let us make a little snow child, and pretend it is a living one.’

‘Yes, let us do that,’ said Ivan, and he took down his cap and went into the garden with his old wife.

Then the two set to work with all their might to make a doll out of the snow. They shaped a little body and two little hands and two little feet. On top of all they placed a ball of snow, out of which the head was to be.

‘What in the world are you doing?’ asked a passer-by.

‘Can’t you guess?’ returned Ivan.

‘Making a snow-child,’ replied Marie.

They had finished the nose and the chin. Two holes were left for the eyes, and Ivan carefully shaped out the mouth. No sooner had he done so than he felt a warm breath upon his cheek. He started back in surprise and looked–and behold! the eyes of the child met his, and its lips, which were as red as raspberries, smiled at him!

‘What is it?’ cried Ivan, crossing himself. ‘Am I mad, or is the thing bewitched?’

The snow-child bent its head as if it had been really alive. It moved its little arms and its little legs in the snow that lay about it just as the living children did theirs.

‘Ah! Ivan, Ivan,’ exclaimed Marie, trembling with joy, ‘heaven has sent us a child at last!’ And she threw herself upon Snowflake (for that was the snow-child’s name) and covered her with kisses. And the loose snow fell away from Snowflake as an egg shell does from an egg, and it was a little girl whom Marie held in her arms.

‘Oh! my darling Snowflake!’ cried the old woman, and led her into the cottage.

And Snowflake grew fast; each hour as well as each day made a difference, and every day she became more and more beautiful. The old couple hardly knew how to contain themselves for joy, and thought of nothing else. The cottage was always full of village children, for they amused Snowflake, and there was nothing in the world they would not have done to amuse her. She was their doll, and they were continually inventing new dresses for her, and teaching her songs or playing with her.

Nobody knew how clever she was! She noticed everything, and could learn a lesson in a moment. Anyone would have taken her for thirteen at least! And, besides all that, she was so good and obedient; and so pretty, too! Her skin was as white as snow, her eyes as blue as forget-me-nots, and her hair was long and golden. Only her cheeks had no colour in them, but were as fair as her forehead.

So the winter went on, till at last the spring sun mounted higher in the heavens and began to warm the earth. The grass grew green in the fields, and high in the air the larks were heard singing. The village girls met and danced in a ring, singing, ‘Beautiful spring, how came you here? How came you here? Did you come on a plough, or was it a harrow?’ Only Snowflake sat quite still by the window of the cottage. Continue reading

Solstice Story

There was the snow, and the snow fell from the heavens, slowly, thoughtful and deliberate, silent contemplation of a million spirits, crystalline and filled with logic, diversity infinite, and yet, each one did come to bless the child.

There was the night, and she was quiet, she was holy, as all nights are, and even when the nights were dancing, loud and full of whirling stars and northern lights performed for all to see or no-one there at all, and winds rush treetops and they tell their tales of night, of all the nights, and know so much, foreshadow even more …

There was the lake, and it was frozen deep and mirror smooth and mirror still, slow water, sleeping water, perhaps it dreams of spring or it may simply rest and think, and gather wisdom of each other, and of time …

There was a thought, a very special wind arose and it could only be right here, right now, and it came softly, lightly, it exhaled the finest mist of white, creates the forms and functions, sculptures in a living dance, they flow and they touch everything, reach into everything, make the connections, make something new, now hush and listen, for the time of magic is upon us, it is nearly here …

There was the child, it stepped in light and whitest shine into this night, and here, the snow did kiss its face, did kiss its hair, and laid itself beneath its feet to be a carpet, be a path, a path that leads in all directions, where you walk, there it becomes.

The night began to sing, so quietly, so full of admiration; the stars awoke and paid attention, sent their light and love to touch the child; the lake became the mirror for it all as now the wind did breathe the future into being and then the child began to smile – his welcome was the holiness, and holiness did enter into all the land touched by his light, it filled the world with hope, with beauty of a different order, the new, the unexpected, a newborn star of purest light.

And there I was, and there were you, and always, ever, always new, there is the snow for us, there is the night, there is the lake, there is wind, and always new, there is the child.

Source: SFX Solstice 2009

James Cheney: Invocation To The Dark Mother

Daniel: Prayer Before The Final Battle

blessed obyno: Queen of Ghosts

blessed obyno: Queen of Ghosts

Caerlion Arthur: The Great, Bloody and Bruised Veil of the World