Fairy Tales and Stories

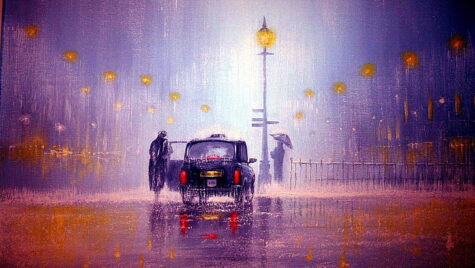

A Yurei Taxi Ghost Story

The cabdriver knew that the ghosts of Japan were not confined to ancient graveyards and shadow-haunted shrines. Any modern resident of the nation’s capital could tell you that the taxis of Tokyo are more haunted than hearses, and his own route took him regularly through open gates to the spirit world.

There was Sendagaya tunnel, which winds beneath the cemetery of Senjuiin Temple, or Shirogane tunnel, where legend has it that screaming faces are silhouetted against the tunnel’s pillars and through which the Shinigami – the spirit of Death itself – is said to pass. All of his fellow cabbies could wax a yarn of passengers who got on then disappeared, or of catching a glimpse of a woman or child’s face in the rear view mirror. He too had a story to tell.

It was a stormy autumn night, near Aoyama Cemetery, where he picked up a poor young girl drenched by the rain. It was dark, so he didn’t get a good look at her face, but she seemed sad and he figured she had been visiting a recently deceased relative or friend. The address she gave was some distance away, and they drove in silence. A good cabbie doesn’t make small talk when picking someone up from a cemetery.

When they arrived at the address, the girl didn’t get out, but whispered for him to wait a bit, while she stared out the window at a 2nd floor apartment. Ten minutes or so passed as she watched, never speaking, never crying; simply observing a solitary figure move about the apartment. Suddenly, the girl asked to be taken to a new address, this one back near the cemetery where he had first picked her up. The rain was heavy, and the driver focused on the road, leaving the girl to her thoughts.

When he arrived at the new address, a modern house in a good neighborhood, the cabbie opened the door and turned around to collect his fare. To his surprise, he found himself staring at an empty back seat, with a deep puddle where the girl had been sitting moments before. Mouth open, he just sat there staring at the vacant seat, until a knocking on the window shook him from his reverie.

The father of the house, seeing the taxi outside, had calmly walked out bringing with him the exact charge for the fare. He explained that the young girl had been his daughter, who died in a traffic accident some years ago and was buried in Aoyama Cemetery. From time to time, he said, she hailed a cab and, after visiting her old boyfriend’s apartment, asked to be driven home. The father thanked the driver for his troubles, and sent him on his way.

~From: Tales of Ghostly Japan, True Tales of Tokyo Terror Taxis

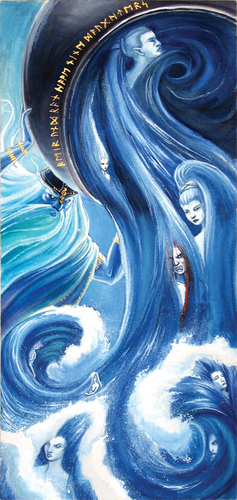

Aegir’s Feast

Ægir was the ruler of the ocean, and his home was deep down below the tossing waves, where the water is calm and still. There was his beautiful palace, in the wonderful coral caves; its walls all hung with bright-colored seaweeds, and the floor of white, sparkling coral sand. Such wonderful sea-plants grew all about, and still more wonderful creatures, some, which you could not tell from flowers, waving their pretty fringes in the water; some sitting fastened to the rocks and catching their food without moving, like the sponges; others darting about and chasing each other.

“Deep in the wave is a coral grove,

Where the purple mullet and goldfish rove;

Where the sea-flower spreads its leaves of blue,

That never are wet with falling dew,

But in bright and changeful beauty shine

Far down in the green and glassy brine.

The floor is of sand, like the mountain drift,

And the pearl-shells spangle the flinty snow;

From coral rocks the sea-plants lift

Their boughs where the tides and billows flow.

The water is calm and still below,

For the winds and waves are absent there,

And the sands are bright as the stars that glow

In the motionless fields of upper air.”

—Percival.

In that ocean home lived the lovely mermaids, who sometimes came up above the waves to sit on the rocks and comb their long golden hair in the sunshine. They had heads and bodies like beautiful maidens, with fish-tails instead of feet.

One day the gods in Asgard gave a feast, and Ægir was invited. He could not often leave home to visit Asgard, for he was always very busy with the ocean winds and tides and storms; but calling his daughters, the waves, he bade them keep the ocean quiet while he was away, and look after the ships at sea.

Then Ægir went over Bifröst, the rainbow bridge, to Asgard, where they had such a gay party and such feasting that he was sorry when the time came to go home; but at last he said good-by to Father Odin and the rest of the Æsir.

He thanked them all for the pleasure they had given him, saying, “If only I had a kettle that held enough mead for us all to drink, I would invite you to visit me.”

Thor, who was always glad to hear about eating and drinking, said, “I know of a kettle a mile wide and a mile deep; I will fetch it for you!”

Then Ægir was pleased, and set a day for them all to come to his great feast.

So Thor took with him his brother, the brave Tyr, who knew best how to find the kettle; and together they started off in Thor’s thunder chariot, drawn by goats, on their way to Utgard, the home of the giants.

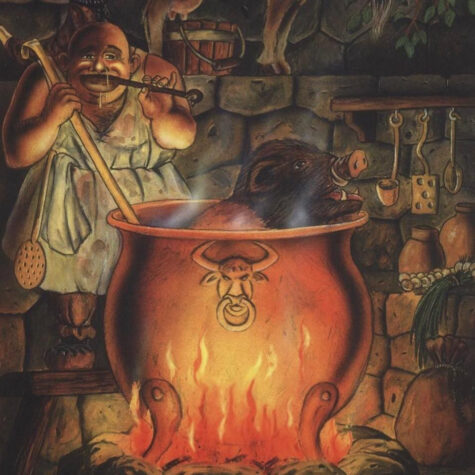

When they reached that land of ice and snow, they soon found the house of Hymir, the giant who owned “Mile-deep,” as the big kettle was called. The gods were glad to find that the giant was not at home, and his wife, who was more gentle than most of her people, asked them to come in and rest, advising them to be ready to run when they should hear the giant coming, and to hide behind a row of kettles which hung from a beam at the back end of the hall.

“For,” said she, “my husband may be very angry when he finds strangers here, and often the glance of his eye is so fierce that it kills!”

At first the mighty Thor and brave Tyr were not willing to hide like cowards; but at last they agreed to the plan, upon the good wife promising to call them out as soon as she had told her husband about them.

It was not long before they heard the heavy steps of Hymir, as he came striding into his icy home; and very lucky it was for Thor and Tyr that the giantess had told them to hide, for when the giant heard that two of the Æsir from Asgard were in his home, so fierce a flash shot from his eyes that it broke the beam from which the kettles hung, and they all fell broken on the floor except Mile-deep.

After a while the giant grew quiet, and at last even began to be polite to his guests. He had been unlucky at his fishing that day, so he had to kill three of his oxen for supper. Thor being hungry, as usual, made Hymir quite angry by eating two whole oxen, so that, when they rose from the table the giant said, “If you keep on eating as much at every meal, as you have to-night, Thor, you will have to find your own food.”

“Very well,” said Thor; “I will go fishing with you in the morning!”

Next morning Thor set forth with the giant, and as they walked over the fields toward the sea, Thor cut off the head of one of the finest oxen, for bait. Of course you may know that Hymir was not pleased at this, but Thor said he should need the very best kind of bait, for he was hoping to catch the Midgard serpent, that dangerous monster who lived at the bottom of the ocean, coiled around the world, with his tail in his mouth.

When they came to the shore where the boat was ready, each one took an oar, and they rowed out to deep water. Hymir was tired first, and called to Thor to stop. “We are far enough out!” he cried “This is my usual fishing-place, where I find the best whales. If we go farther the sea will be rougher, and we may run into the Midgard serpent.”

As this was just what Thor wanted, he rowed all the harder, and did not stop until they were far out on the ocean; then he baited his hook with the ox’s head, and threw it overboard. Soon there came a fierce jerk on the line; it grew heavier and heavier, but Thor pulled with all his might. He tugged so hard that he broke through the bottom of the boat, and had to stand on the slippery rocks beneath.

All this time the giant was looking on, wondering what was the matter, but when he saw the horrid head of the Midgard serpent rising above the waves, he was so frightened that he cut the line; and Thor, after trying so hard to rid the world of that dangerous monster, saw him fall back again under the water; even Miölnir, the magic hammer, which Thor hurled at the creature, was too late to hit him. And so the two fishermen had to turn back, and wade to the shore, carrying the broken boat and oars with them.

The giant was proud to think he had been too quick for Thor, and after they reached the house he said to the thunder-god, “Since you think you are so strong, let us see you break this goblet; if you succeed, I will give you the big kettle.”

This was just what Thor wanted; so he tightened his belt of strength, and threw the goblet with all his might against the wall; but instead of breaking the goblet he broke the wall.

A second time he tried, but did no better. Then the giant’s wife whispered to Thor, “Throw it at his head!” And she sang in a low voice, as she turned her spinning-wheel,—

“Hard the pillar, hard the stone,

Harder yet the giant’s bone!

Stones shall break and pillars fall,

Hymir’s forehead breaks them all!”

Yet again Thor threw the goblet, this time against the giant’s head, and it fell, broken in pieces.

Then Tyr tried to lift the Mile-deep kettle, for he was in a hurry to leave this land of ice and snow; but he could not stir it from its place, and Thor had to help him, before they could get it out of the giant’s house.

When Hymir saw the gods, whom he hated, carrying off his kettle, he called all his giant friends, and they started out in chase of the Æsir; but when Thor heard them coming he turned and saw their fierce, grinning faces glaring down at him from every rocky peak and iceberg.

Then the mighty Thunderer raised Miölnir, the hammer, above his head, and hurled it among the giants, who became stiff and cold, all turned into giant rocks, that still stand by the shore.

Ægir was very glad to get Mile-deep; so he set to work to make the mead in it, to get ready for the great feast, at the time of the flax harvest, when all the Æsir were coming from Asgard to visit him.

Before the day came, all light and joy had gone from the sacred city, because the bright Baldur had been slain, and the homes of the gods were dark and lonely without him. So they were all glad to visit Ægir, to find cheer for their sadness.

There was Father Odin, with his golden helmet, and Queen Frigga, wearing her crown of stars, golden-haired Sif, Freyja, with Brisingamen, the wonderful necklace, and all the noble company of the Æsir, all except mighty Thor, who had gone far away to the giant-land.

As they all sat in Ægir’s beautiful ocean hall, drinking the sweet mead, and talking together, Loki came in and stood before them; but, finding he was not welcome, and no seat saved for him, he began saying ugly things to make them all angry, and at last he grew angry himself, and slew Ægir’s servant because they praised him.

The Æsir drove him out from the hall, but once more he came in, and said such dreadful things that at last Frigga said, “Oh, if my son Baldur were only here, he would silence thy wicked tongue!”

Then Loki turned to Frigga, and told her that he himself was the very one who had slain Baldur. He had no sooner spoken than a heavy peal of thunder shook the hall, and angry Thor strode in, waving his magic hammer. Seeing this, the coward Loki turned and fled, and Asgard was rid of him forever.

Source: Fairytalez

Little Violette ~ The Zombie Child

Violette was born into one of the wealthiest families in Old New Orleans to Robért and Yvette. They once lived in a beautiful home on the edge of the Old Quarter on lands then owned by members of the great Marigny family. But though they were wealthy and rich in love, for several years the greatest blessing – that of a healthy child seemed to elude them.

On the advice of an elderly aunt, Robert sought the help of one of the most famous physicians then practicing in New Orleans, Dr. Joseph Victor Gottschalk, known to all as “Physician, Surgeon, Occultist and Accoucheur.” Gottschalk was to serve his clients only too well, for when his skills as physician helped produce the desired result – pregnancy in Yvette – his services as an “accoucheur,” the French name for male mid-wife, were then also required.

Violette came into the world in one of those vibrant New Orleans springs. They named her Violette as her eyes were of the color of pure amethyst. For the first time, the couple felt their married life was now complete. The child thrived under the care of Dr. Gottschalk who had secured a mulatto woman to provide constant care for the beautiful little girl. Violette’s life was of pampered elegance, because her parents had so longed for a child. The doctor himself presented little Violette with a pair of beautiful amethyst earrings, a mere reflection of the color of her eyes, that had been sent to him by his sister Adelaide in Philadelphia as a gift for the little girl.

Robert’s business often took him to more distant areas of the estates where he was supposed to have acted on behalf of Count Marigny in the capacity of manager of the estate overseers. Little Violette would watch wide-eyed when her father rode away to work and would wait patiently in her nursery, sometimes for several days, for his return.

Eventually, as she grew, she made her discontent with Robert’s absence well known, throwing a tantrum every time he prepared to depart and insisting that he take her with him. Yvette, however, always objected to the mere suggestion that Robert might take Violette into the swampy lowlands and woods of the unoccupied estates where she might be exposed, so Yvette assumed, to all sorts of dangers, not the least of which were the slaves and Native Indians who resided there

One day Yvette received a message that her mother was ill and Yvette was adamant that Violette should not make the rigorous trip perhaps to be exposed to the dangers of the road. So Violette was to remain at home in the care of her mulatto nurse while Yvette went to her mother’s aid. Now it was said that the nurse always spoiled the now five-year-old Violette, giving in to her whims and letting her have almost anything she asked for. So it was that on a day when Robert was departing and Violette was embroiled in another of her violent tantrums the well-meaning nurse gave in to Violette’s demands to accompany her father. And Robert, seeing no harm in it, agreed to take the little girl along.

On the fifth day Robert came running home carrying Violette in his hands. Dr. Gottschalk was immediately summoned who took Robert aside. The news was grave. Violette had contracted a delirium fever, possibly Scarlet fever or malaria, and it had so drained her tiny body that there was little hope of her survival. “But I do not expect that she will be with us tomorrow”, said the physician. Robert, already wracked with guilt at having taken Violette against his wife’s constant wishes. Just before dawn she passed away.

Gottschalk made the funeral arrangements for Violette as her father Robert succumbed to his grief and could not be comforted. Word was sent to St. John’s Parish to tell Yvette that her dearest child was no more. They laid Violette in the soil of the Esplanade Ridge and were loathe to leave her there when the time came to go. Robert and Yvette were terribly grieved. All business, all domestic obligations seemed to come to a complete halt and had it not been for the reliable servants, the home and lands might have gone derelict.

Now in those days money might buy anything. Whether in league with God or the Devil, Robert did not care. He would find the person who would help him put an end to his pain and bring back the mind of his beloved wife. Thus, lurking outside the gates of Congo Square in the wild torchlight of one of the great vodoun “bamboulas,” Robert made the hellish pact with the mavens of Marie Laveau’s secret sosyete. They had agreed to attempt to bring back his beloved Little Violette.

The decaying 1 month old corpse of Little Violette was removed from her resting place in the old Bayou Cemetery and taken to a secret location where for one full cycle of the moon it was subjected to the most powerful vodoun magic that had been performed by that most secret sosyete up to that time.

One night there came a knock at the front door. The couple rushed to open it and was puzzled to see an old vodusi matron standing there, with Violette. The couple burst into tears of joy and happiness. Yvette scooped the little girl into her trembling arms. With violet eyes once again burning with life, the little girl said in a familiar voice like the sound of tinkling glass: “Mama!” With that, the couple’s joy seemed complete.

The woman was denied from visiting their home ever again after bring paid a hefty lumpsum. And joyful it was, at least for a time. When the servants learned of the child’s return they were puzzled as to how the child was reanimated. The mulatto nurse was the most frightened of all the house servants. Fear kept them all in place: fear of what she might be capable of doing.

The once beautiful and vibrant Violette was now somehow different; something about her was never quite “right” and none of the servants liked being in her presence very long. Deep inside the house, pattering footsteps deep in the night troubled the servants; grunting sounds or the sounds of furtive eating could be heard in the darkness outside, but no one had the nerve to investigate.

And while all this happened, Robert and Yvette seemed only to see Violette, living in a perpetual dream state, under the child’s spell. First it was the little night creatures that were found dead, hidden under the spreading low branches or covered in moss in the roots of trees. Some looked as if they had been scaled and skinned alive by claws; others were torn in half, with parts missing.

Another strange occurrence was the disappearance of meat stock in the smoke house and pantry. No fresh cut of meat was safe, evidently, and although at first the cook staff were puzzled they became outright fearful when they observed marks in some of the cured meat that looked as if it had been gnawed upon by little HUMAN teeth… Robert and Yvette seemed blissfully unaware of the change, the servants watched in horror as the little girl seemed, for all intents and purposes, to be decomposing before their eyes. The black magic workers, who instead of restoring her to wholesome life had zombified her!

Now the servants knew they were trapped in a horrible nightmare, and fearful for their own lives they first determined to leave the home. But it was the memory of the beautiful little Violette, the vibrant happiness she had brought to them all when she was alive, that combined with their fierce loyalty to her parents to keep them there. So it was that they made a pact among themselves when the opportunity presented itself, would take the zombie child from the home and kill it, or, if it could not be killed, then bind it to keep it from returning. But they knew they could attempt this without the aid of a powerful vodoun patron.

It is said that they took their case to the daughter of Marie Laveau, Mamzelle Marie, and begged for her aid. Not surprisingly, Mamzelle Marie was angered by what she saw as a horrible act that went against the practices of her mother’s sosyete and the vodoun beliefs in the sanctity of life and death. On the night that the servants appealed to her, Mamzelle Marie said to them: “For Violette, I will give you strength to do this thing. For Violette.”

Of all people it was the faithful mulatto nurse who found the courage and the strength to face the little creature that had taken the place of her beloved Violette. Alone with the zombie child in the grim nursery, the mulatto woman was able to overcome her worst fears and trap the horrible creature in a bedsheet. Tying it tightly in knots and praying in the Krayol language of vodoun, the nurse rushed to a wagon that waited to take her to a rendezvous with Mamzelle Marie herself.

When she arrived at the appointed place, the nurse was surprised to find Mamzelle was not alone: with her was the old vodusi woman who had brought the zombified Violette home. Thinking at first that she had been betrayed, the nurse was reluctant to turn over the kicking bundle that contained the zombie baby. But a look from Mamzelle Marie reassured her and she handed the bundle over to the powerful vodoun mambo.

As soon as Mamzelle Marie took hold of her, the zombie Violette burst into a horrific tantrum, it sounded more like the ravings of a caged animal; there were even marks from the zombie child’s fingernails as she began to claw her way out. Mamzelle Marie shouted a word of Command and the tantrum stopped, then she turned to the nurse. “Go home,” she told her, “and perform the house cleansing ritual that I taught you earlier. Turn your back on this child immediately and forget her. She is in my charge now.”

Violette the zombie child never did return to the house of her parents, who, once she had been removed, seemed to return as if from a dream world; even their grieving had ceased. The loyal servants never mentioned anything about the horrible visitation of the zombie child, nor did the nurse ever reveal what she had done with it. A year and a day from the moment the nurse relinquished the child to Mamzelle Marie, the young couple was blessed with another child: this time a son came to live with Robert and Yvette.

It is said, the old vodusi was made to take the zombie child home to live with her. She kept the zombie Violette confined, but when she died there was no trace to be found of Voilette. No one ever knew for certain, but most other vodusi and members of the secret sosyetes assumed that the old woman had finally found a way to destroy the creature she had made.

Generations later the new owners of this home – Mark and Andy purchased the house. They felt that there was something – a residual haunting or possibly an entity – in the home. Andy was constantly complaining about the sound of cats yowling. He and Mark would stand in the kitchen and listen to what sounded like a cat trapped in the other side, yowling to be let out.

When they investigated there was nothing found until one day, when Mark was home alone working on the empty side scraping the old plaster from the gabled ceiling of the little bathroom. As he worked, he revealed what appeared to be a small door; assuming it went into the attic, Mark put some elbow grease into it and by the time Andy returned that evening they could both see the outline of a little trap door. It had been painted shut under the plaster coating and had all the appearances of having been sealed for generations.

Working together they were able to pry the little door open.Peering into the darkness of the attic gable, pushing aside the bones of dead pigeons and rats, sorting through a rusty pile of chains and tattered rags, they came upon what appeared to be an old doll. It was the size of a young child, but it appeared for all intents and purposes to be a mummy doll wrapped in layers of tattered cloth – sheets, curtains, ropes, even lace and a kind of gauze around the face. What caught their eyes though, even in the dim light of the attic, was the dazzling purple flash of a pair of amethyst earrings, still brilliant – and still attached – even after all the intervening years.

Something about the horrid, lifelike “doll” terrified Andy and he insisted that the rickety attic door remain nailed shut at all times. Although Mark wanted to take the thing out of it’s attic home, Andy was having none of that and confessed later that he could barely stand living in the other side of the house knowing the little “creature” was in the empty attic. He even considered moving out at one point, when the confusion of Hurricane Katrina came roaring into everyone’s lives. Mark and Andy were forced to evacuate their home during the storm.

When they returned to their home after the storm they discovered minor damage to their side and a collapsed Chinaberry tree piercing the roof of the empty side. Both men agree that their hearts fell when they saw this and not just because of the horror of insurance claims and FEMA paperwork. It was as if, they said, they “knew” the broken roof meant trouble.

Reluctantly, Mark held the ladder while Andy bravely went to the little attic door and, with a feeble flashlight, looked inside. The mummified doll was nowhere.

Source: Stories That Shocked The World

The Lycanthropous Flower

From the book Werwolves, by Elliott O’Donnell, first published in 1912, we have this account of the case of the family of Kloska and the Lycanthropous flower.

In the mountainous regions of Austria-Hungary and the Balkan Peninsula are certain flowers credited with the property of converting into werewolves whoever plucks and wears them. Needless to say, these flowers are very rare, but I have heard of their having been found, comparatively recently, both in the Transylvanian Alps and the Balkans.

A story a propos of one of these discoveries was told me last summer.

Ivan and Olga were the children of Otto and Vera Kloska – the former a storekeeper of Kerovitch, a village on the Roumanian side of the Transylvanian Alps. One morning they were out with their mother, watching her wash clothes in a brook at the back of their house, when, getting tired of their occupation, they wandered into a thicket.

“Let’s make a chaplet of flowers,” Olga said, plucking a daisy. “You gather the flowers and I’ll weave them together.”

“It’s not much of a game,” Ivan grumbled, “but I can’t think of anything more exciting just now, so I’ll play it. But let’s both make wreaths and see which makes the best.”

To this Olga agreed, and they were soon busily hunting amidst the grass and undergrowth, and scrambling into all sorts of possible and impossible places.

Presently Ivan heard a scream, followed by a heavy thud, and running in the direction of the noise, narrowly avoided falling into a pit, the sides of which were partly overgrown with weeds and brambles.

“It’s all right,” Olga shouted; “I’m not hurt. I landed on soft ground. It’s not very deep, and there’s such a queer flower here – I don’t know what it is; I’ve never seen one like it before.”

Ivan’s curiosity thus aroused, he carefully examined the sides of the pit, and, selecting the shallowest spot, lowered himself slowly over and then dropped. It was nothing of a distance, seven or eight feet at the most, and he alighted without mishap on a clump of rank, luxuriant grass. “See! here it is,” his sister cried, pointing to a large, very vivid white flower, shaped something like a sunflower, but soft and pulpy, and full of a sweet, nauseating odour. “It’s too big to put in a wreath, so I’ll wear it in my buttonhole.”

“Better not,” Ivan said, snatching it from her; “I don’t like it. It’s a nasty-looking thing. I believe it’s a sort of fungus.”

Olga then began to cry, and as Ivan was desirous of keeping the peace, he gave her back the flower. She was a prepossessing child, with black hair and large dark eyes, pretty teeth and plump, sunburnt cheeks. Nor was she altogether unaware of her attractions, for even at so early an age she had a goodly share of the inordinate vanity common to her sex, and liked nothing better than appearing out-of-doors in a new frock plentifully besprinkled with rosettes and ribbons.

The flower, she told herself, would look well on her scarlet bodice, and would be a good set-off to her black hair and olive complexion. All this was, of course, beyond the comprehension of Ivan, who regarded his sister’s weakness with the most supreme contempt, and for his own part was never so happy as when skylarking with other boys and getting into every conceivable kind of mischief. Yet for all that he was in the main sensible, almost beyond his years, and extremely fond, and – though he would not admit it – proud of Olga.

She fixed the flower in her dress, and imitating to the best of her knowledge the carriage of royalty, strutted up and down, saying “Am I not grand? Don’t I look nice? Ivan – salute me!”

And Ivan was preparing to salute her in the proper military style, taught him by a great friend of his in the village, a soldier in the carabineers for whom he had an intense admiration, when his jaw suddenly fell and his eyes bulged.

“Whatever is the matter with you?” Olga asked.

“There’s nothing the matter with me,” Ivan cried, shrinking away from her; “but there is with you. Don’t! don’t make such faces – they frighten me,” and turning round, he ran to the place where he had made his descent and tried to climb up.

Some minutes later the mother of the children, hearing piercing shrieks for help, flew to the pit, and, missing her footing, slipped over the brink, and falling some ten or more feet, broke one of her legs and otherwise bruised herself.

For some seconds she was unconscious, and the first sight that met her eyes on coming to was Ivan kneeling on the ground, feebly endeavoring to hold at bay a gaunt grey wolf that had already bitten him about the legs and thigh, and was now trying hard to fix its wicked white fangs into his throat.

“Help me, mother!” Ivan gasped; “I’m getting exhausted. It’s Olga.”

“Olga!” the mother screamed, making frantic efforts to come to his assistance. “Olga! what do you mean?”

“It’s all owing to a flower – a white flower,” Ivan panted; “Olga would pluck it, and no sooner had she fixed it on her dress than she turned into a wolf! Quick, quick! I can’t hold it off any longer.”

Thus adjured the wretched woman made a terrific effort to rise, and failing in this, clenched her teeth, and, lying down, rolled over and over till she arrived at the spot where the struggle was taking place. By this time, however, the wolf had broken through Ivan’s guard, and he was now on his back with his right arm in the grip of his ferocious enemy.

The mother had not a knife, but she had a long steel skewer she used for sticking into a tree as a means of fastening one end of her washing line. She wore it hanging to her girdle, and it was quite by a miracle it had not run into her when she fell.

“Take care, mother,” Ivan cried, as she raised it ready to strike; “remember, it is Olga.”

This indeed was an ugly fact that the woman in her anxiety to save the boy had forgotten. What should she do? To merely wound the animal would be to make it ten times more savage, in which case it would almost inevitably destroy them both. To kill it would mean killing Olga. Which did she love the most, the boy or the girl?

Never was a mother placed in such a dilemma. And she had no time to deliberate, not even a second. God help her, she chose. And like ninety-nine out of a hundred mothers would have done, she chose the boy; he – he at all costs must be saved. She struck, struck with all the pent-up energy of despair, and in her blind, mad zeal she struck again.

The first blow, penetrating the werewolf’s eye, sank deep into its brain, but the second blow missed – missed, and falling aslant, alighted on the form beneath.

An hour later a villager on his way home, hearing extraordinary sounds of mirth, went to the side of the pit and peeped over.

“Vera Kloska!” he screamed; “Heaven have mercy on us, what have you there?”

“He! he! he!” came the answer. “He! he! he! My children! Don’t they look funny? Olga has such a pretty white flower in her buttonhole, and Ivan a red stain on his forehead. They are deaf – they won’t reply when I speak to them. See if you can make them hear.”

But the villager shook his head. “They’ll never hear again in this world, mad soul,” he muttered. “You’ve murdered them.”

The Fox Wedding

“Once upon a time there was a young white fox, whose name was Fukuyemon. When he had reached the fitting age, he shaved off his forelock and began to think of taking to himself a beautiful bride. The old fox, his father, resolved to give up his inheritance to his son, and retired into private life; so the young fox, in gratitude for this, labored hard and earnestly to increase his patrimony.

Now it happened that in a famous old family of foxes there was a beautiful young lady-fox, with such lovely fur that the fame of her jewel-like charms was spread far and wide. The young white fox, who had heard of this, was bent on making her his wife, and a meeting was arranged between them. There was not a fault to be found on either side; so the preliminaries were settled, and the wedding presents sent from the bridegroom to the bride’s house, with congratulatory speeches from the messenger, which were duly acknowledged by the person deputed to receive the gifts; the bearers, of course, received the customary fee in copper cash.

When the ceremonies had been concluded, an auspicious day was chosen for the bride to go to her husband’s house, and she was carried off in solemn procession during a shower of rain, the sun shining all the while. After the ceremonies of drinking wine had been gone through, the bride changed her dress, and the wedding was concluded, without let or hindrance, amid singing and dancing and merry-making.

The bride and bridegroom lived lovingly together, and a litter of little foxes were born to them, to the great joy of the old grandsire, who treated the little cubs as tenderly as if they had been butterflies or flowers. “They’re the very image of their old grandfather,” said he, as proud as possible. “As for medicine, bless them, they’re so healthy that they’ll never need a copper coin’s worth!”

As soon as they were old enough, they were carried off to the temple of Inari Sama, the patron saint of foxes, and the old grand-parents prayed that they might be delivered from dogs and all the other ills to which fox flesh is heir.

In this way the white fox by degrees waxed old and prosperous, and his children, year by year, became more and more numerous around him; so that, happy in his family and his business, every recurring spring brought him fresh cause for joy. “

~From Algernon Freeman-Mitford’s Tales of Old Japan, 1910

Another Case of Lycanthropy

From the book Werwolves, by Elliott O’Donnell, first published in 1912, we have this account of the case of a Lycanthropous brook in the Harz Mountains.

Another case of lycanthropy in Germany, connected with the Harz Mountains, occurred somewhere about the beginning of the last century.

Count Von Breber, chief of the police of Magdeburg, whilst away from home on a holiday with his young and beautiful wife, the Countess Hilda, happened to pass a night in the village of Grautz, in the centre of the Harz Mountains.

In the course of a conversation with the innkeeper, the Countess remarked: “On our way here this morning we crossed a brook, and experienced the greatest difficulty in persuading our dogs to go into the water. It is most unusual, as they are generally only too ready for a dip. Can you in any way account for it?”

“Were there two very tall poplars, one on either side of the brook?” the innkeeper asked; “and did you notice a peculiar – one cannot describe it as altogether unpleasant – smell there?”

“We did!” the Count and Countess exclaimed in chorus.

“Then it was the spot locally known as Wolf Hollow,” the innkeeper said. “No one ventures there after dark, as it has a very evil reputation.”

“Stuff and nonsense!” the Count snapped.

“That is as your honour pleases,” the innkeeper said humbly. “We village folk believe it to be haunted; but, of course, if the subject appears ridiculous to you, I will take care I do not refer to it again.”

“Please do!” the Countess cried. “I love anything to do with the supernatural. Tell us all about it.”

The innkeeper gave a little nervous cough, and glancing uneasily at the Count, whose face looked more than usually stern in the fading sunlight, observed: “They do say, madam, that whoever drinks the water of that stream…”

“Yes, yes?” the Countess cried eagerly.

“Suffers a grave misfortune.”

“Of what nature?” the Countess demanded; but before the innkeeper could answer, the Count cut in:

“I forbid you to say another word. The Countess has drunk the water there, and your cock-and-bull stories will frighten her into fits. Confess it is all made up for the benefit of travellers like ourselves.”

“Yes, your honour!” the innkeeper stammered, his knees shaking; “I confess it is mere talk, but we all be – be – lieve it.”

“That will do – go!” the Count cried; and the innkeeper, terrified out of his wits, flew out of the room.

Some minutes later mine host received a peremptory summons to appear before the Count, who was alone and scowling horribly, in the best parlour. He had barely got inside the room before the Count burst out wrathfully:

“I’ve sent for you, sir, in order to impress upon you the fact that if either you or your minions mention one word about that brook to the Countess, or to her servants – mark that – I will have the breath flogged out of your body and your tongue snipped. Do you hear?”

“Y – yes, your honour,” the innkeeper cried. “I ful – fully un – understand, and if her ladyship asks me any – anything abou – out the br – br – brook, I will lie.”

“Which won’t trouble you much, eh?”

“N – n – o, your honour! I mean y – yes, your honour! It will be a burden on my con – conscience, but I will do anything to pl – please your honour.”

The interview then terminated, and the innkeeper, bathed in perspiration and wishing his lot in life anything but what it was, hastened to prepare dinner.

“I hope nothing dreadful will happen to me; I feel that something will,” the Countess said, as she let down her long beautiful hair that night. “Carl, why did you let me drink the water?”

“The water be – – !” the Count growled. “Didn’t you hear what the innkeeper said? – that the story was mere invention! If you believe all the idle tales you hear, you will soon be in an asylum. Hilda, I’m ashamed of you!”

“And I’m ashamed of myself,” the Countess cried, “so there!” and she flung her arms round his neck and kissed him.

The following morning they left the inn, and, retracing their steps, journeyed homewards. The Count looked at his wife somewhat critically; she was very pale, and there were dark rims under her eyes.

“I do believe, Hilda,” he observed with an assumed gaiety, “you are still worrying about that water!”

“I am,” she replied; “I had such queer dreams.”

He asked her to narrate them, but she refused; and as her sleep now became constantly disturbed, and she was getting thin and worried, the Count determined that as soon as he reached home he would call in a doctor. The latter, examining the Countess, attributed the cause of her indisposition to dyspepsia, and ordered her a diet of milk food. But she did not get better, and now insisted upon sleeping alone, choosing a bedroom situated in a secluded part of the house, where there was absolute silence.

The Count remonstrated. “You might at least let me occupy the room next to you!” he said.

“No,” she replied; “I should hear you if you did. I am sensible now of the very slightest sounds, and besides disturbing me, they are a source of the greatest annoyance. I feel I shall never get well again unless I can have complete rest and quiet. Do let me!” and she fixed her big blue eyes on him so earnestly, that he vowed he would see that all her wishes, no matter how fanciful, were gratified.

“I hope she won’t go mad!” he said to himself; “her behaviour is odd, to say the least of it. Odd! – wholly inexplicable.”

It was rather too bad that just now, when his mind was harassed with misgivings at home, he should also be bothered with disturbances outside his own home. But so it was. Events of an unprecedented nature were taking place in the town, and it fell to his lot to cope with them. Night after night children – mostly of the poorer class – disappeared, and despite frantic yet careful and thorough searches, no clue as to what had befallen them had, so far, been discovered.

The Count doubled the men on night duty, but in spite of these and other extraordinary precautions the disappearances continued, and the affair – already of the utmost gravity – promised to be one that would prove disastrous, not merely to the heads of families, but to the head of the police himself.

So long as the missing ones had been of the lower orders only, the Count had not had much to fear – the murmurings of their parents could easily be held in check – but now that a few of the children of the rich had been spirited away, there was every likelihood of the matter reaching the ears of the Court.

One evening, when the Count had hardly recovered his equanimity after a stormy interview with Herr Meichen, the banker, whose three-year-old daughter had vanished, and a still more distressing scene with Otto Schmidt, the lawyer, whose six-year-old daughter had disappeared, his patience was called upon to undergo a still further trial in consequence of a visit from General Carl Rittenberg, a person of the greatest importance, not only in the town, but in the whole province. Purple in the face with suppressed fury, the General burst into the room where the head of the police sat.

“Count!” he cried, striking the table with his fist, “this is beyond a joke. My child – my only child – Elizabeth, whom my wife and I passionately love, has been stolen. She was walking by my side in Frederick Street this afternoon, and as it suddenly became foggy, I left her a moment to hail a vehicle to take us home. I wasn’t gone from her more than half a minute at the most, but when I returned she had gone.

I searched everywhere, shouting her name; and passers by, compassionate strangers, joined me in my search; but though we have looked high and low not a trace of her have we been able to discover. I have not told her mother yet. God help me – I dare not! I dare not even show my face at home without her – my wife will never forgive me – – “; and so great was his emotion that he buried his face in his hands, and his great body heaved and shook.

Then he started to his feet, his eyes bulging and lurid. “Curse you!” he shrieked; “curse you, Count! it’s all your fault! Day after day you’ve sat here, when you ought to have been hunting up these rascally police of yours. You’ve no right to rest one second – not one second, do you hear? – till the mystery surrounding these poor lost children has been cleared up, and, living or dead – God forbid it should prove to be the latter! – they are restored to their parents.

“Now, mark my words, Count, unless my child Elizabeth is found, I’ll make your name a byword throughout the length and breadth of the country – I’ll – – “; but words failed him, and, shaking his fist, he staggered out of the room.

The Count was much perturbed. The General was one of the few people in the town who really had it in their power to do him harm – the one man above all others with whom he had hitherto made it his business to keep in. He had not the least doubt but that the General meant all he said, and he recognized only too well that his one and only hope of salvation lay in the recovery of Elizabeth. But, God in heaven, where could he look for her?

Sick at heart, he marshaled every policeman in the force, and within an hour every street in Magdeburg was being subjected to a most rigorous search. The Count was just quitting his office, resolved to join in the hunt himself, when a shabbily dressed woman brushed past the custodian at the door, and racing up to him, flung herself at his feet.

“What the devil does she want?” the Count demanded savagely. “Who is she?”

“Martha Brochel, your honour, a poor half-witted creature, who was one of the first in the town to lose a child,” the door-porter replied; “and the shock of it has driven her mad!”

“Mad! mad! Yes! that is just what I am – mad!” the woman broke out. “Everything is in darkness. It is always night! There are no houses, no chimneys, no lanterns, only trees – big, black trees that rustle in the wind, and shake their heads mockingly. And then something hideous comes! What is it? Take it away! Take it away! Give her back to me!” And as Martha’s voice rose to a shriek, she threw her hands over her head, and, clenching them, growled and snarled like a wild animal.

“Put her outside!” the Count said with an impatient gesture; “and take good care she does not get in here again.”

“No! Don’t turn me away! Don’t! don’t!” Martha screamed; “I forgot what it was I wanted to tell you – but I remember now. I’ve seen it! – seen the thing that stole my child. There is light – light again! Oh! hear me!”

“Where have you seen it, Martha?” the porter inquired; and looking at the Count, he said respectfully: “It is just possible, your honour, this woman might be of use to us, and that she has actually seen the person who stole her child.”

“Rubbish! What right has she to have children?” the Count snapped, and he spurned the supplicant with his boot.

The moment she was in the street, however, the head of the police was after her. Keeping close behind her, he resolutely dogged her steps. The evening was now far advanced, and the fog so dense that the Count, though he knew the city, was soon at a total loss as to his whereabouts. But on and on the woman went, now deviating to the right, now to the left; sometimes pausing as if listening, then tearing on again at such a rate that the Count was obliged to run to keep up with her. Suddenly she uttered a shrill cry:

“There it is! There it is! The thing that took my child!” and the figure of what certainly appeared to be a woman, muffled, and carrying a sack on her shoulder, glided across the road just in front of them and disappeared in the impenetrable darkness. Martha sped after her, and the Count, his hopes raised high, followed in hot pursuit. He failed to recognize the ground they were traversing, and presently they came to a high wall, over which Martha scrambled with the agility of an acrobat.

The Count, in attempting to imitate her, damaged his knee and tore his clothes, but he also landed safely on the other side. Then on they went, Martha with unabated energy, the Count horribly exhausted, and beginning to think of turning back, when they were abruptly brought to a standstill. The walls of some building loomed right ahead of them. The object of their pursuit, again visible, darted through a doorway; whilst Martha, with a loud cry of triumph, sprang in after her; but before the Count could cross the threshold the door was slammed and locked in his face.

Then he heard a chorus of the most appalling sounds – sounds so strange and unearthly that his blood turned to ice and his hair rose straight on end. Rushing footsteps mingled with peculiar soft patterings; agonized human screams coupled with the growls and snappings of an animal; a heavy thud; gurgles; and then silence.

The Count’s courage revived: he hurled himself against the door; it gave with a crash, and the next moment he was inside. But what a sight met his eyes! The place, which somehow or the other seemed oddly familiar to him, was a veritable shambles – floor, walls, and furniture were sodden with blood. In every corner were mangled human remains; whilst stretched on the ground, opposite the doorway, lay the body of Martha, her face unrecognizable and her breast and stomach ripped right open.

This was terrible enough, but more terrible by far was the author of it all, who, having cast aside wraps, now stood fully revealed in the yellow glow of a lantern. What the Count saw was a monstrosity – a thing with a woman’s breast, a woman’s hair, golden and curly, but the face and feet were those of a wolf; whilst the hands, white and slender, were armed with long, glittering nails, cruelly sharp and dripping with blood.

To the Count’s astonishment the creature did not attack him, but uttering a low plaintive cry, veered round and endeavoured to escape. But escape was the very last thing Van Breber would permit. Whatever the thing was – beast or devil – it had caused him endless trouble, and if allowed to get away now, would go on with its escapades, and so bring about his ruin.

No! he must kill it. Kill it even at the risk of his own life. With a shout of wrath he plunged his sword up to its hilt in the thing’s back.

It fell to the floor and the Count bent over it curiously. Something was happening – something strange and terrifying; but he could not look – he was forced to shut his eyes. When he opened them he no longer saw the hairy visage of a wolf – he was gazing fondly into the dying eyes of his beautiful and much-loved wife. With a rapidity like lightning, he recognized his surroundings. He was in a long disused summer-house that stood in a remote corner of his own grounds!

“God help me and you, too!” the Countess Hilda whispered, clasping him fondly in her arms. “It was the water! – the water I drank in the Harz Mountains! I have been bewitched…”; and kissing him feverishly on the lips, she sank back – dead.

The Harz Mountain Werewolves

From the book Werwolves, by Elliott O’Donnell, first published in 1912, we have this account of the case of Herr Hellen and the Werewolves of the Harz Mountains.

Two gentlemen, named respectively Hellen and Schiller, were on a walking tour in the Harz Mountains, in the early summer of the year 1840, when Schiller, slipping down, sprained his ankle and was unable to go on. They were some miles from any village, in the centre of an extensive forest, and it was beginning to get dark.

“Leave me here,” cried the injured man to his friend, “while you see if you can discover any habitation. I have been told these woods are full of charcoal-burners’ and wood-cutters’ huts, so that if you walk straight ahead for a mile or two, you are very likely to come across one. Do go, there’s a good fellow, and if you are too tired to return yourself, send some one to carry me.”

Hellen did not like leaving his comrade in such a dreary spot, alone and helpless, but as Schiller was persistent he at length yielded, and stepping briskly out, advanced along the track that had brought them hither. Once or twice he halted, fancying he heard voices, and several times his heart pulsated wildly at what he took to be the cry of a wolf – for neither Schiller nor he had no weapons excepting sheath-knives.

At last he came to an open spot hedged in on all sides by gloomy pines, the shadows from which were beginning to fall thick and fast athwart the vivid greensward. It was one of those places – they are to be found in pretty nearly every country – studiously avoided by local woodsmen as the haunt of all manner of evil influences.

Hellen recognized it as such the moment he saw it, but as it lay right across his path, and time was pressing, he had no alternative but to keep boldly on. He was half-way across the spot when he was startled by a groan, and looking in the direction of the sound, he saw a man seated on the ground endeavouring to bandage his hand. Wondering why he had not observed him before, but thankful to meet some one at last, Hellen went up to him and asked what was the matter.

“I’ve broken my wrist,” the man replied. “I was gathering sticks for my fire to-morrow when I heard the howl of a wolf, and in my anxiety to escape a conflict with the brute I climbed this tree. As I descended one of the branches gave way, and I fell down with all my weight on my right arm. Will you see if you can bind it for me? I’m a bit awkward with my left hand.”

“I will do my best,” Hellen said, and kneeling beside the man, he took off the bandages and wrapped them round again. “There,” he exclaimed, “I think that is better – at least it is the best I can do.”

The stranger was now most profuse in his thanks, and when Hellen informed him of Schiller’s condition, at once cried out, “You must both come to my cottage; it is only a short distance from here. Let us hasten thither now, and my daughter, who is very strong, shall go back with you and help you carry your friend. We are not rich, but we can make you both fairly comfortable, and all we have shall be at your disposal. But I wonder if you know what you have incurred by coming to this spot at this hour?”

“Why, no,” Hellen said, laughing. “What?”

“The gratification of two wishes – the first two wishes you make! Of course, you will say it is all humbug, but, believe me, very queer things do happen in this forest. I have experienced them myself.”

“Well!” Hellen replied, laughing more heartily than before, “if I wish anything at all it is that my wife were here to see how beautifully I have bandaged your wrist.”

“Where is your wife?” the stranger inquired.

“At Frankfort, most likely taking a final peep at the children in bed before retiring to rest herself!” Hellen said, still laughing.

“Then you have children!” the stranger ejaculated, evidently interested.

“Yes, three – all girls – and such bonny girls, too. Marcella, Christina, and Fredericka. I wish I had them here for you to see.”

“I should much like to see them, certainly,” the stranger said. “And now you have told me so much of interest about yourself, let me tell you something of my own history in exchange. My name is Wilfred Gaverstein. I am an artist by profession, and have come to live here during the summer months in order to paint nature – nature as it really is – in all its varying moods. Nature is my only god – I adore it. I don’t believe in souls. I love the trees and flowers and shrubs, the rivulets, the fountains, the birds and insects.”

“Everything but the wolves!” Hellen remarked jocularly. Hardly, however, had he spoken these words before he had reason to alter his tone. “Great heavens! do you hear that?” he cried. “There is no mistake about it this time. It is a wolf, or may I never live to hear one again.”

“You are right, friend,” Wilfred said. “It is a wolf, and not very far away, either. Come, we must be quick,” and thrusting his arm through that of Hellen, he hurried him along. After some minutes’ fast walking they came in sight of a neatly thatched whitewashed cottage, at the entrance to which two women and several children were collected. “That’s my home,” Wilfred said.

“And that’s my wife!” Hellen cried, rubbing his eyes to make sure he was not dreaming. “God in heaven, what’s the meaning of it all? My wife and children – all three of them! Am I mad?”

“It is merely the answer to your wishes,” Wilfred rejoined calmly. “See, they recognize you and are waving.”

As one in a sleep Hellen now staggered forward, and was soon in the midst of his family, who, rushing up to him, implored him to explain what had happened, and how on earth they came to be there.

“I am just as much at sea as you are,” Hellen said, feeling them each in turn to make sure it was really they. “It’s an insoluble mystery to me.”

“And to us, too,” they all cried. “A few minutes ago we were in our beds in Frankfort, and then suddenly we found ourselves here – here in this dreadful looking forest. Oh, take us away, take us home, do!”

Hellen was in despair. It was all like a hideous nightmare to him. What was he to do?

“You must be my guests for to-night, at all events,” Wilfred said; “and in the morning we will discuss what is to be done. Fortunately we have enough room to accommodate you all. There is food in abundance. Let me introduce you to my daughter Marguerite,” and the next moment Hellen found himself shaking hands with a girl of about twenty years of age.

She was clad in what appeared to be a travelling dress, deeply bordered with white fur, and wore a most becoming cap of white ermine. Her feet were shod in long, pointed, and very elegant buckskin shoes, adorned with bright silver buckles. Her hair, which was yellow and glossy, was parted down the middle, and waved in a most becoming fashion low over the forehead and ears; and her features – at least so Hellen thought – were very beautiful.

Her mouth, though a trifle large, had very daintily cut lips, and was furnished with unusually white and even teeth. But there was a peculiar furtive expression in her eyes, which were of a very pretty shape and colour, that aroused Hellen’s curiosity, and made him scrutinize her carefully. Her hands were noticeably long and slender, with tapering fingers and long, almond-shaped, rosy nails, that glittered each time they caught the rays of the fast fading sunlight.

Hellen’s first impression of her was that she was marvellously beautiful, but that there was a something about her that he did not understand – a something he had never seen in anyone before, a something that in an ugly woman might have put him on his guard, but in this face of such surpassing beauty a something he seemed only too ready to ignore. Hellen was a good, and up to the present, certainly, a faithful husband, but he was only a man after all, and the more he looked at the girl the more he admired her.

At a word from Wilfred, Marguerite smilingly led the way indoors, and showed the guests two bedrooms, small but exquisitely clean. There was a double bed in one, and two single ones in the other. The bed-linen was of the very finest material, and white as snow.

“I think,” Wilfred remarked, “two of the girls can squeeze in one bed – they are neither of them very big – though it does my heart good to see them so bonny.”

“And mine, too,” Marguerite joined in, patting the three children on the cheeks in turn, and drawing them to her and caressing them.

Mrs. Hellen, still dazed, and apparently hardly realizing what was happening, stammered out her thanks, and the party then descended to the kitchen to partake of a substantial supper that was speedily prepared for them.

“Had you not better go and look for your friend now?” Wilfred observed, just as Hellen was about to seat himself beside his wife and children. “Marguerite will go with you, and on your return the three of you can have your meal in here after the children have gone to bed.”

Hellen readily assented, and kissing his wife and little ones, who tearfully implored him not to be gone long, set out, accompanied by Marguerite.

At each step they took, Marguerite’s beauty became more irresistible. The soft rays of the moon falling directly on her features enhanced their loveliness, and Hellen could not keep his eyes off her. The ominous cry of a night bird startled her; she edged timidly up to him; and he had to exert all his self-control, so eager was he to clasp her to him.

In a strained, unnatural manner he kept up a flow of small-talk, eliciting the information that she was an art student, and that she had studied in Paris and Antwerp, had exhibited in Munich and Turin, and was contemplating visiting London the following spring. They talked on in this strain until Hellen, remembering their mission, exclaimed:

“We must be very close to where I left Schiller. I will call to him.”

He did so – not once, but many times; and the reverberation of his voice rang out loud and clear in the silence of the vast, moon-kissed forest. But there was no response, nothing but the rustling of branches and the shivering of leaves.

“What’s that?” Marguerite suddenly cried, clutching hold of Hellen’s arm. “There! right in front of us, lying on the ground. There!” and she indicated the object with her gleaming finger-tip.

“It looks remarkably like Schiller,” Hellen said. “Can he be asleep?”

Quickening their pace, they speedily arrived at the spot. It was Schiller, or rather what had once been Schiller, for there was now very little left of him but the face and hands and feet; the rest had only too obviously been eaten. The spectacle was so shocking that for some minutes Hellen was too overcome to speak.

“It must have been wolves!” he said at length. “I fancied I heard them several times. Would to God I had never left him! What a death!”

“Horrible!” Marguerite whispered, and she turned her head away to avoid so harrowing a sight.

“Well,” Hellen observed in a voice broken with emotion, “it’s no use staying here. We can’t be of any service to him now. I will gather the remains together in the morning, and with the assistance of your father see that they are decently interred. Come! let us be going.” And offering Marguerite his arm, they began to retrace their steps.

For some time Hellen was too occupied with thoughts of his friend’s cruel death to think of anything else, but the close proximity of Marguerite gradually made itself felt, and by the time they had reached the open clearing – the spot where he had encountered Wilfred – his passion completely overpowered him.

Throwing discretion to the winds, and oblivious of wife, children, home, honour, everything save Marguerite – the lustre of her eyes and the dainty curving of her lips – he slipped his arm round her waist, and pressing her close to him, smothered her in kisses.

“How dare you, sir!” she panted, slowly shaking herself free. “Aren’t you ashamed of such behaviour? What would your wife say, if she knew?”

“I couldn’t help it,” Hellen pleaded. “I’m not myself to-night. Your beauty has bewitched me, and I would risk anything to have you in my arms.” He spoke so earnestly and looked at her so appealingly that she smiled.

“I know I am beautiful,” she said, and the intonation of her voice thrilled him to the very marrow of his bones. “Dozens of men have told me so. Consequently, since there seems to have been some excuse for you, I forgive you, only – – ,” but before she could say another word, Hellen had again seized her, and this time he did not loosen his hold till from sheer exhaustion he could kiss her no more.

“It’s no use!” he panted. “I can’t help it. I love you as I never loved a woman before, and if you were to ask me to do so I would go to Hell with you this very minute.”

“It is dangerous to express such sentiments here,” Marguerite said. “Don’t you know this spot is full of supernatural influences, and that the first two things you wish for will be granted?”

“I have already wished,” Hellen said. “I wished when I was here with your father.”

“Then wish again,” Marguerite replied; “I assure you your wishes will be fulfilled.” And again she looked at him in a way that sent all the blood in his body surging wildly to his head, and roused his passion in hot and furious rebellion against his reason.

“I wish, then,” he cried, seizing hold of her hands and pressing them to his lips – “I wish every obstacle removed that prevents my having you always with me – that is wish number one.”

“And wish number two?” the girl interrogated, her warm, scented breath fanning his cheeks and nostrils. “Won’t you wish that you may be mine for ever? Always mine, mine to eternity!”

“I will!” Hellen cried. “May I be yours always – yours to do what you like with – in this life and the next.”

“And now you shall have your reward,” Marguerite exclaimed, clapping her hands gleefully. “I will kiss you of my own free will,” and throwing her arms round his neck, she drew his head down to hers, and kissed him, kissed him not once but many times.

An hour later they left the spot and slowly made their way to the cottage. As they neared it, loud screams for help rent the air, and Hellen, to his horror, heard his wife and children – he could recognize their individual voices – shrieking to him to save them.

In an instant he was himself again. All his old affection for home and family was restored, and with a loud answering shout he started to rush to their assistance. But Marguerite willed otherwise. With a dexterous movement of her feet she got in his way and tripped him, and before he had time to realize what was happening, she had flung herself on the top of him and pinioned him down.

“No!” she said playfully, “you shall not go! You are mine, mine always, remember, and if I choose to keep you here with me, here you must remain.”

He strove to push her off, but he strove in vain; for the slender, rounded limbs he had admired so much possessed sinews of steel, and he was speedily reduced to a state of utter impotence.

The shrieks from the cottage were gradually lapsing into groans and gurgles, all horribly suggestive of what was taking place, but it was not until every sound had ceased that Marguerite permitted Hellen to rise.

“You may go now,” she said with a mischievous smile, kissing him gaily on the forehead and giving his cheeks a gentle slap. “Go – and see what a lucky man you are, and how speedily your first wish has been gratified.”

Sick with apprehension, Hellen flew to the cottage. His worst forebodings were realized. Stretched on the floor of their respective rooms, with big, gaping wounds in their chests and throats, lay his wife and children; whilst cross-legged, on a chest in the kitchen, his dark saturnine face suffused with glee, squatted Wilfred.

“Fiend!” shouted Hellen. “I understand it all now. I have been dealing with the Spirits of the Harz Mountains. But be you the Devil himself you shan’t escape me,” and snatching an axe from the wall, he aimed a terrific blow at Wilfred’s head.

The weapon passed right through the form of Wilfred, and Hellen, losing his balance, fell heavily to the ground. At this moment Marguerite entered.

“Fool!” she cried; “fool, to think any weapon can harm either Wilfred or me. We are phantasms – phantasms beyond the power of either Heaven or Hell. Come here!”

Impelled by a force he could not resist, Hellen obeyed – and as he gazed into her eyes all his blind infatuation for her came back.

“We must part now,” she said; “but only for a while – for remember, you belong to me. Here is a token” – and she thrust into his hand a wisp of her long, golden hair. “Sleep on it and dream of me. Do not look so sad. I shall come for you without fail, and by this sign you shall know when I am coming. When this mark begins to heal,” she said, as, with the nail on the forefinger of the right hand, she scratched his forehead, “get ready!”

There was then a loud crash – the room and everything in it swam before Hellen’s eyes, the floor rose and fell, and sinking backwards he remembered no more.

When he recovered he was lying in the centre of the haunted plot. There was nothing to be seen around him except the trees – dark lofty pines that, swaying to and fro in the chill night breeze, shook their sombre heads at him. A great sigh of relief broke from him – his experiences of course had only been a dream.

He was trying to collect his thoughts, when he discovered that he was holding something tightly clasped in one of his hands. Unable to think what it could be, he rose, and held it in the full light of the moon. He then saw that it was a tuft of white fur – the fur of some animal.

Much puzzled, he put it in his pocket, and suddenly recollecting his friend, set out for the place where he had left him. “I shall soon know,” he said to himself, “whether I have been asleep all this time – God grant it may be so!”

His heart beat fearfully as he pressed forward, and he shouted out “Schiller” several times. But there was no reply, and presently he came upon the remains, just as he had seen them when accompanied by Marguerite.

Convinced now that all that had taken place was grim reality, he went back along the route Schiller and he had taken the preceding day, and in due time reached the village. To the landlord of the inn where they had stayed he related what had happened.

“I am truly sorry for you,” the landlord said; “your experience has indeed been a terrible one. Every one here knows the forest is haunted in that particular spot, and we all give it as wide a berth as possible. But you have been most unfortunate, for Wilfred and Marguerite, who are werwolves, only visit these parts periodically. I last heard of them being seen when I was about ten years of age, and they then ate a pedlar called Schwann and his wife.”

As soon as Schiller’s remains had been brought to the village and interred in the cemetery, Hellen, armed to the teeth and accompanied by several of the biggest and strongest hounds he could hire – for he could get none of the villagers to go with him – spent a whole day searching for Wilfred’s cottage. But although he was convinced he had found the exact spot where it had stood, there were now no traces of it to be seen.

At length he returned to the village, and on the following morning set out for Frankfort. On his arrival home he was immediately apprised of the fact that a terrible tragedy had occurred in his house. His wife and children had been found dead in their beds, with their throats cut and dreadful wounds in their chests, and the police had not been able to find the slightest clue to the murderers.

With a terrible sinking at the heart Hellen asked for particulars, and learned, as he knew only too well he would learn, that the date of the tragedy was identical with that of his adventure in the forest.

He tried hard to persuade himself that the coincidence was a mere coincidence; but – he knew better. Besides, there was the scratch! – the scratch on his forehead.

Moreover, the scratch remained. It remained fresh and raw till a few days prior to his death, when it began to heal. And on the day he died it had completely healed.

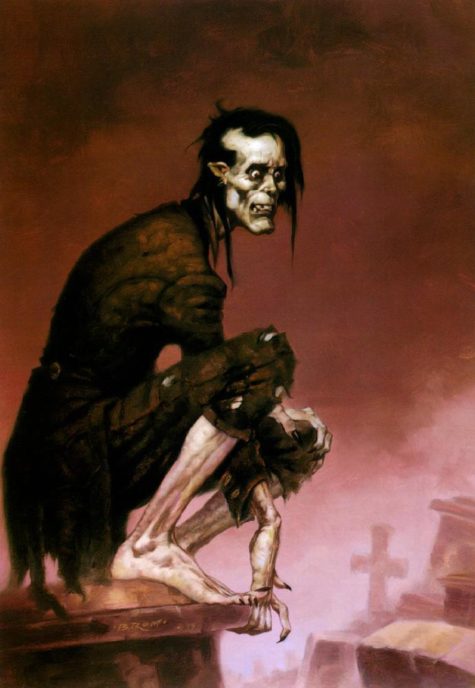

The Ghoulish Case of Constance Armande

From the book Werwolves, by Elliott O’Donnell, first published in 1912, we have this account of the ghoulish case of Constance Armande.

The following incident was related to me as having occurred recently in Brittany. A young girl named Constance Armande, in a good station of life, much against the wishes of her family, took up spiritualism and constantly attended seances.

At these seances she witnessed all sorts of phenomena – some in all probability produced by mere trickery on the part of the medium or a confederate, whilst others were, without doubt, the manifestations of bona fide spirits – earthbound phantasms of the lowest and most undesirable order – murderers, lunatics, Vice Elementals, and ghouls.

It is most unwise to risk coming in contact with such spirits, for when they have once made your acquaintance they will attach themselves to you, and are got rid of only with the greatest difficulty. They were most unremitting in their persecution of Constance Armande; they followed her home, and were always rapping on the walls of her room and disturbing and annoying her.

In short, she got no peace, either asleep or awake. In the night she would often wake up screaming, and in an agony of mind rush into her parents’ room and implore their protection, declaring she had dreamed in the most vivid manner possible that frightful-looking creatures, too awful for her to describe, were trying to prevent her awaking in order to keep her with them always.

She told a spiritualist, and he informed her that such dreams were not in reality dreams at all, but projections – that she had, at seances, acquired the power of projection; and, having no control over that power, she projected herself unconsciously, the projection almost always taking place in her sleep.

A medical expert was also consulted, and in accordance with his advice Constance Armande went to the seaside and resorted to every kind of pleasure – balls, concerts, and theatres. But the annoyances still continued, and she was seldom permitted to rest a whole night without being disturbed in a most harrowing manner.

Being a really beautiful girl, she had countless admirers, and eventually she became engaged to Alphonse Mabane, the only son of a very wealthy widow.

Shortly before the day fixed for their marriage Madame Mabane was seized with a fit of apoplexy and died. Every one, especially Constance Armande, was overwhelmed with grief, whilst preparations were made for a most impressive funeral.

On the afternoon of the day preceding that on which the funeral was to take place Constance, complaining of a bad headache, went to lie down on her bed, and two hours later strange footsteps were heard coming out of her room and bounding down the stairs. Wondering who it could be, Madame Armande ran to look, and was astonished beyond measure to see Constance – but a Constance she hardly knew – a Constance with the glitter of a ferocious beast in her eyes, and a grim, savage expression in the corners of her mouth.

She did not appear to notice her mother, but passed her by with a light, stealthy tread, utterly unlike her usual walk, crossed the hall, and went out at the front door. Madame Armande was too startled to try and intercept her, or even to make any remark, and returned to the drawing-room greatly agitated.

As hour after hour passed and Constance did not come home, her alarm increased, and she mentioned the incident to her husband, who caused immediate inquiries to be made. Just about the hour the family usually retired to rest there came a violent ring at the front-door bell. It was Alphonse Mabane, pale and ghastly.

“Have you found her?” Monsieur and Madame Armande cried, catching hold of him in their agitation, and dragging him into the hall.

Alphonse nodded. “Let me sit down a moment first,” he gasped. “It will give me time to collect my senses. My nerves are all to pieces!”

He sank into a chair, and, burying his face in his hands, shook convulsively. Monsieur and Madame Armande stood and watched him in agonized silence. After some minutes – to the Armandes it seemed an eternity – spent in this fashion, Alphonse raised his head.

“Your servant,” he said, “came to my house at nine o’clock and asked if Mademoiselle Constance was with me. I said ‘No,’ that I had not seen her all day, and was much alarmed when I was informed that she had left home early in the afternoon and had not yet returned.

I said I would join in the search for her, and was in my bedroom putting on my overcoat, when there came a tap at my door, and Jacques, my valet, with a face as white as a sheet, begged me to go with him upstairs. He led me to the door of my mother’s room, where she lay in her coffin, not yet screwed down. ‘Hark!’ he whispered, touching me on the sleeve, ‘do you hear that?’

“I listened, and from the interior of the room came a curious noise like munching – a steady gnaw, gnaw, gnaw. ‘I heard it just now,’ he whispered, ‘when I was going to shut the landing window – and other sounds, too. Hush!’

“I held my breath, and heard distinctly the swishing and rustling of a dress.

“‘Have you been in?’ I asked.

“He shook his head. ‘I daren’t,’ he whispered. ‘I wouldn’t go in by myself if you were to offer me a million pounds,’ and he trembled so violently that he had to lean against me for support.

“A great terror then seized me, and bidding Jacques follow, I crept downstairs and summoned the rest of the servants. Armed with sticks and lights, we then went in a body to my mother’s room, and throwing open the door, rushed in.

“The lid of the coffin was off, the corpse was lying huddled up on the floor, and crouching over it was Constance. For God’s sake don’t ask me to describe more – the sounds we heard explained everything. When she saw us she emitted a series of savage snarls, sprang at one of the maids, scratched her in the face, and before we could stop her, flew downstairs and out into the street. As soon as our shocked senses had sufficiently recovered we started off in pursuit, but have not been able to find the slightest trace of her.”

At the conclusion of Monsieur Mabane’s story the search was continued. The police were summoned, and a general hue and cry raised, with the result that Constance was eventually found in a cemetery digging frantically at a newly made grave.

At last brought to bay in the chase that ensued, fortunately for her and for all concerned, she plunged into a river, was swept away by the current, and drowned.

This case of Constance Armande seems to me to be clearly a case of ghoulism. What the spiritualist had told her was correct – she had projected herself unconsciously, and the hideous things she imagined were phantoms in a dream were Elementals – ghouls – her projected spirit encountered on the superphysical plane.

After sundry efforts to steal her body when she was thus separated from it, one of them had at length succeeded, and, incarcerated in her beautiful frame, had hastened to satisfy its craving for human carrion.

A Ghoulish Story

The case of Sergeant Bertrand, which is the last authenticated case of this kind, occurred in 1847, when, on the 10th of July, an investigation was held before a military council presided over by Colonel Manselon.

For some months the cemeteries in and around Paris had been the scenes of frightful violations, the culprits (or culprit), in some extraordinary manner, eluding every attempt made to ensnare them. At one time the custodians of the cemeteries were suspected, then the local police, and for a brief space suspicion fell even on the relations of the dead.

The first burial-place to be so mysteriously visited was the Cemetery of Pere Lachaise. Here, at night, those in charge declared they saw a strange form, partly human and partly animal, glide about from tomb to tomb. Try how they would they could not catch it – it always vanished – vanished just like a phantom directly they came up to it; and the dogs when urged to seize it would only bark and howl, and show indications of the most abject terror.

Always when morning broke the ravages of this unsavoury visitant were only too plainly visible – graves had been dug up, coffins burst open, and the contents nibbled, and gnawed, and scattered all over the ground. Expert medical opinion was sought, but with no fresh result. The doctors, too, were agreed that the mutilations of the dead were produced by the bites of what certainly seemed to be human teeth.