Monthly Archives: October 2018

Bat Symbolism, Mythology, and Lore

For fans of horror movies, the bat has become an animal to be feared. It not only becomes entangled in long hair, but the vampire bat is a satanic agent that sucks the soul from the body along with its life blood. However, there is more to the bat than purely negative symbolism.

Culturally, the bat symbolized great luck and wealth to the Chinese. The Mayans saw them as symbols of rebirth. Europeans believed that the human soul took the form of a bat during sleep time and then people could leave their bodies. This led to the belief that Pagans might become bats when they die, and then they might search for a means of rebirth or the blood of life.

Bat Symbolism

The bat is a symbol of rebirth and depth because it is a creature that lives in the belly of the Mother (Earth). From the womb-like caves it emerges every evening at dusk. And so – from the womb it is reborn every evening.

Bat- Death and Rebirth, Guardian of the Night, Cleaner

The nocturnal nature of the bat has given it some negative associations. It is symbolic of the night devouring the day. The bat is said to swallow the light because it wakes at dusk, the time between day and night. Native Indian tribes in Brazil say that a bat swallowing the Sun will herald the end of the world, and the Mayans believed that the bat was a harbinger of death. Christian belief, too, regards the bat with suspicion because it is seen as an incarnation of Satan.

However, the nocturnal nature of the bat makes it, like the owl, a creature that has access to hidden knowledge and secret information, able to detect things in the hours of darkness that are not accessible to diurnal creatures. Before echolocation was recognized and understood, the bat’s ability to find its way about was a source of great intrigue, adding to the mystique of the animal.

The bat is also symbol of communication because the Native Americans observed the bat to be a highly social creature. Indeed, the bat has strong family ties. They are very nurturing, exhibiting verbal communication, touching, and sensitivity to members of their group.

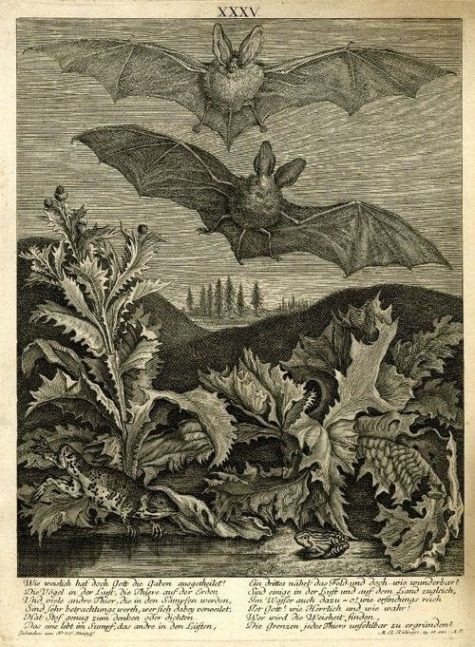

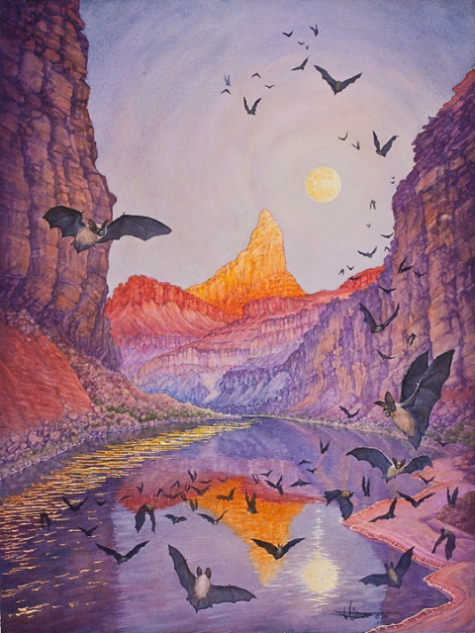

As flying creatures, bats signify the sky, but they have many qualifications for Underworld symbolism as well. They hang upside-down, facing the Underworld; they are nocturnal (the Underworld is dark); they roost in caves or dead trees and use streams as flyways (caves, tree roots, and streams were considered openings into the Underworld).

In some South American myths, honey, bees, and bats are related or interchangeable. In other folklore, bats are classed with hummingbirds and butterflies, animals that sometimes visit the same flowers by day that bats feed from by night.

Omens and Signs:

What does it mean when you see a bat? It can mean a number of different things depending on where you are from, and what the situation with the bat is. Here are some common beliefs:

- If a bat flies into your house, look out for bedbugs.

- A bat flying into a building means it’s going to rain.

- It’s unlucky to see a bat in the daytime.

- Killing a bat shortens your life.

- Bats in a church during a wedding ceremony is a bad omen.

- Bats in the house mean either a death or a sign that the humans will soon be leaving.

- If a bat flies close to a person it means that person will be betrayed.

- Bats flying vertically upwards then dropping back to earth means that ‘The Witches Hour Has Come’

- Bats are symbolic of bad luck, especially if they cry while flying.lying early in the evening.

- Flying bats might also mean good weather.

- If a bat flies into the house and then gets away, there will be a death in the family. Kill the bat before it escapes, however, and everyone will be alright.

- If a bat flies into the kitchen and at once hangs on to the ceiling, it is lucky; but if it circles around twice before alighting, it is bad.

- To the Chinese and the Polish, the bat means long life and happiness, a good omen.

Folklore from Nova Scotia relates that if the bat alights in the house, a man in the family will die, whereas if it flies around, a woman’s death is foretold. If someone in the house is sick, they will die, but this can be avoided if a handful of salt is thrown into the fire.

A woman from California stated that if a pregnant woman sees a bat, her child will die. Other myths are that bats in a house indicate the death of a parent or of a very good friend. Folklore from Illinois asserts that if a bat enters a house and stays for a long time, there will be a death in the house, but if it does not stay long, a relative will die.

In New Mexico lore, the death will occur within eight days, while myths from the midwestern United States state that the death will occur either in a month, or within six months. Myth from Washington specifies that death will occur within a year.

Many legends say that the bat does not even have to enter the house or the actual living quarters to be a harbinger of death. Myths from Slovinian, German, and Jewish immigrants relate that bats in an attic foretell a death in the house. From numerous places and ethnic groups we’re also told that a bat simply flying over a house, or at a window, or down a chimney can mean death.

From western New York comes a tale that claims if a bat flies around a house while a dog is howling, it is a sure sign of death for someone in the house. An Arkansas myth says that dreaming about bats flying in your house will mean the death of a dear friend.

Some folklore asserts that mortal consequences can be averted, but in typical fashion, there are other myths to contradict this. More contemporary beliefs are related by a man in Las Vegas and a woman from Tacoma who both claim that death could be prevented simply by killing the bat. But beliefs from the Midwest predict exactly the opposite, foretelling a person’s death only if the bat is killed, and just sickness if the bat escapes.

In Ohio, a woman of Scottish ancestry related that when a bat flies in a doorway, a person can avoid serious illness by drinking a mixture of his or her burned hair and coffee. From Arkansas comes a report on how to avoid the issue altogether; it claims that placing a horseshoe in the fireplace will scare bats away.

Bats in buildings have also been seen as omens of lesser evils than death. Various myths relate that bats in houses may bring bad luck, or portend that someone in the house will go insane, become blind, be missing the next day, that a letter with bad news will arrive, or that the people in the house will move.

Zuni Indian myths, along with lore from North Carolina, Arkansas, and Illinois, all corroborate that bats flying around a chimney, or attempting to enter a building, are a sure sign of rain.

While of less consequence than death, woe be it to the bridal couple who has the misfortune to marry in a church with bats in the belfry. A great deal of very bad luck is predicted if a bat flies into the church during a wedding ceremony.

While European and North American folklore about bats in buildings generally views bats as portents of misfortune or evil, some benign lore also exists perceiving them as good omens. For example, if a bat lives in a theater, and flies over the stage during rehearsal, the play is guaranteed success.

A contemporary local story comes from Indians in California who relate that a bat flying in a house foretells a good hunting season. And finally, miners working in the mountains of Nevada insist that a mine will be safe if a bat remains in the mineshaft after blasting.

Other cultures also view bats in a human dwelling as a good omen. Merlin Tuttle relates that in his research in the northern and western part of Kenya, the Nandi and Lugen peoples welcome bats into their homes as bringers of good luck. Their presence is thought to help increase wealth and make livestock reproductively prolific. But even within the same country and region, views can contrast sharply. The Kisii people of western Kenya are said to very fearful of bats, sometimes abandoning their homes if bats enter, fearing ill health and death of their children.

Other European and North American myths give a positive interpretation of bats in houses, but as is often the case in folklore, the death of the bat–sometimes in a rather gruesome ritual–is usually required to interpret the bat as a good sign.

A recent story comes from a woman in Illinois who related that if a bat enters a house that has a small baby inside, the child will cut teeth better if the bat is killed and its carcass is kept overnight in the house. She said that her family did this when a bat entered her daughter’s house, and that her grandchild “didn’t have any trouble when cutting teeth.”

Lore from Montreal, Canada, relates that a bat flying into a house will bring financial prosperity to the household, but only if the bat is caught and allowed to die after its hind legs have been cut off. Once the poor animal is dead, its legs must be buried at least a foot deep in the back yard.

One very widespread myth about bats in houses, however, has nothing to do with bad–or good–omens. There is a persistent belief that bats enter your house to steal food. One of the most common traditional beliefs about bats in houses, repeated throughout Europe and by immigrants in North America, is that bats are extremely fond of fat. The lore states that they will gnaw on hams and slabs of bacon, which in former times were hung to cure in chimneys and well-ventilated rooms–places where bats were often discovered roosting.

This belief is reflected in a German word for bat (speckmaus, speck being the German word for bacon), and also in period illustrations and nursery rhymes. Bats were clearly getting the blame for other animal thieves; in his 1939 book, Bats, G.M. Allen speculates that rats were the true predators. It also seems probable that birds, which people often purposely attract by hanging suet, may have been among the real culprits. Allen describes experiments conducted in Germany in the early nineteenth century in which captive bats were offered a diet of bacon but refused it and starved to death.

If you keep in mind that bats were viewed as evil spirits, or even the devil, it is not difficult to understand why folklore about them appearing in one’s own home focuses largely on death, illness, and misfortune. Also, we should appreciate that in earlier times, houses were much more than good investments and income tax breaks; they were a person’s safe refuge from many very real dangers. The bat, as a devil or evil spirit, was seen as entering this sanctum with malevolent intent. Typically, the devil is after souls, and this accounts for the frequent association of a bat’s appearance in a building with death.

This devil/evil spirit association is specific in many myths. Bats are commonly said to indicate that the house they frequent is haunted, and an old German myth relates that if a bat flies into your house, the devil is after you. But redemption is sometimes possible once a bat enters your home. By killing the bat, one might be able to minimize its evil effects or even gain grace with good forces.

Recognizing the devil/evil spirit association, we can certainly understand why a bat appearing uninvited during a wedding in a church, the Lord’s house, would be seen as an extremely bad omen. Another view is found in African-American folklore, which relates that if a bat enters your house and leaves without staying long, it is because the evil spirits did not feel welcome.

With the plethora of myths handed down from so many cultures, perhaps we can come to understand some of the often irrational fears and behavior people exhibit when confronted with the presence of a small, harmless (and likely terrified) bat in their home.

Bats As An Animal Totem

If the bat has been “flying” into your life as an animal totem, this symbolizes great intuition and utilizing your sensitivities to explore the world around you. The bat has been misunderstood by many over the years and most people fear this creature, but many medicine people and the Native Americans sought the bat for its connection to the “other world.”

Bats have a special way of “seeing,” and they don’t use their regular eyes to see, but rather they use a built in sensor, a type of radar called echolocation, that guides them during flight at night time. For this reason, bats were revered for their special “vision,” and medicine people often invoked bat energy if they wanted to “see” clearer into a situation.

- What Do Bats Symbolize?

Bats are misunderstood because of the folklore dealing with vampires. However, bats are highly social creatures; they love to congregate with their family in huge numbers inside caves. They often hang upside down inside their cave (also called a roost), and only emerge at dusk to feed on insects (a common time for insects to stir). For this reason, the bat has come to symbolize rebirth because they go “inside” their cave which represents going within, and then they emerge at dusk, and this is seen as being reborn from the womb of mother Earth.

If this animal totem has appeared to you in your dreams or in waking life perhaps it is a sign that it is time for you to go within. It might be time to take some time off and go on a vacation and bring a journal with you, or even just try meditation as a way of becoming quiet and allowing your true self to speak.

Once bats have emerged from their cave, and they are experiencing the outside world, they are highly attuned to their surroundings. The highly sensitive bat can pick up movement of prey as well as avoid colliding with fellow bats during flight by using echolocation.

- What does it mean?

If the bat has appeared as your totem, this means that you are on a journey of awakening to your psychic gifts. If the bat has chosen you, this means that you will have a chance to improve your abilities and yourself ten-fold. You may find this a bit challenging as you will be called to go within and explore ALL of you, the light and dark side. You will be asked to explore your inner demons and learn to love them.

As you do this, you will find yourself learning to not only love your enemies but even the darkest parts of yourself. When you accomplish this, you will realize the profound rewards that come from having compassion for your fellow man and all of his follies through learning to love your own.

And once you have reached this state, you will find that your devotion to your spiritual path with strengthen and journeying within will become easier and easier. The nice thing about this is as you learn to face your demons more and more, you will realize that what is being offered to you is the gift of constant self-improvement and this means that you get to EVOLVE!

The bat is your companion on your spiritual journey and will guide you to deep places where you can begin to see things not as good and bad, but just as they are. With the bat by your side, you can learn to face your deepest fears and to accept yourself fully. This animal totem has entered your life to help you reach your highest potential by showing you that the first step in accessing your gifts is by first loving yourself fully and then and only then can you emerge into the light.

Key words:

- Intuition

- Connection

- Communication

- Journeying Within

- Rebirth

- Evolution

- Loving Self

- Psychic Vision

If you have the bat as your totem you are extremely aware of your surroundings. Sometimes you can be overly sensitive to the feelings of others. Additionally, you are quite perceptive on a psychic level, and are prone to have prophetic dreams.

If you work with the bat as your totem, you will be put to the test, because it is demands only 100% commitment to spiritual growth. The bat will never accept half-hearted or lukewarm attempts at self-improvement. Indeed, if the bat senses that you are slacking in your psychic/spiritual training it will likely move on to someone else who is more willing to learn the lessons the bat has to offer.

The bat reminds us that even in darkness, we have the resources to see our way. As with most of our hardest challenges, working with the demanding bat will reap some of the most profound rewards you could ever dream of.

But be warned, the bat asks a lot of us, like:

- Dying to our ego

- Loving our enemies as ourselves

- Going within to touch our inner demons

- Exploring the underworlds of reality (which can be scary)

- Renewing our thoughts and beliefs on a moment-to-moment basis

All of these tasks can be harrowing experiences. This is why the Native American symbolism of the bat deals with initiation; because this creature takes us to outlandish extremes. But rest assured, the bat is never leaves our side while we are journeying.

Furthermore, once we are tested to satisfaction, the devotion of the bat will never fade. It will eternally support us on our spiritual path – ever faithful and forever loving us on our journey to maintain our highest potential.

Why are Bats tied to Halloween?

Seasonally, bats are tied to Halloween and this is because when the fall season’s bonfires were lit, it attracted thousands of insects which in turn attracted the bats for a feeding frenzy. Because this happens in the fall, this is another reason why the bat is seen as a symbol of transition and change (not only for the season but for humans experiencing life change as well).

More Bat Lore:

In both ancient Greece and Rome, it was thought that sleep could be prevented either by placing the engraved figure of a bat under the pillow, or by tying the head of a bat in a black bag and keeping it near to the left arm. In the Ivory Coast, even today many think that bats are the spirits of the dead, and in Madagascar, they are assumed to be the souls of criminals, sorcerers and the unburied dead. In the Tyrol it is believed that the man who wears the left eye of a bat may become invisible, and in Hesse he who wears the heart of a bat bound to his arm with red thread will always be lucky at cards.

Wash your face in bat’s blood, and you will be able to see in the dark; keep a bat bone in your pocket will ensure good luck; powdered bat heart will staunch bleeding or stop a bullet; bullets from a gun swabbed with a bat’s heart will always hit their target; bat’s blood into someone’s drink will make them more passionate; stimulate a woman’s desire by placing a clot of bat blood under her pillow; use a hair wash of crushed bat wings in coconut oil and it will prevent both baldness and graying of the hair.

While stories of bats in general abound in the myth and lore of many New World peoples, ironically, surprisingly little folklore exists specifically about vampire bats. They do not appear to be mentioned at all in the lore of the Aztecs, one of the largest civilizations of ancient Mesoamerica. The Maya, however, revered a vampire bat god, “Camazotz,” the death bat, who killed dying men on their way to the center of the earth. “Zotz” was the Maya word for bat.

Bats and Witches

Linking bats to witchcraft and magic has given rise to many of the fears people have about bats. Today in the United States, we see this association in Halloween decorations, horror movies, and scary novels, but it reaches back into antiquity and is found in many parts of the world. Throughout history, bats have often been considered the familiars or even the alter egos of witches.

In 1332, Lady Jacaume of Bayonne in France was publicly burned because “crowds of bats” were seen about her house and garden. Shakespeare invoked bats and witches in several of his plays. The “wool of bat” in the brew of Macbeth’s three witches is a prominent example of the association, as is Caliban’s curse on Prospero in The Tempest:

“All the charms of Sycorax,

toads, beetles and bats, light on you.”

The use of bats in witchcraft survives even in modern times. As recently as 1957, a California taxidermist sold bat blood, presumably for witchcraft. Other contemporary references include a report from Ohio claiming that bat blood can call evil spirits, and another from Illinois asserting that it gives witches “the power to do anything.” There are also reports of bats used for witchcraft in Mexico’s Yucatan, and bat wings are often in the conjure bags of African-Americans in Georgia.

But not all myths bring to mind frightening acts; some ascribe wondrous magical properties to bats and associate good luck with them. Unfortunately for the bat, most of them require its demise. An ancient belief found both in the American Midwest and the Caribbean is that bathing your eyes in bat blood will allow you to see in the dark.

Many other beliefs suggest that bats have the power to make people invisible. In Trinidad there is an old belief that if you drank the blood of a bat, you would become invisible. Tyrolean gypsies have a similar belief, claiming that carrying the left eye of a bat will accomplish the feat. In Oklahoma carrying the right eye of a bat pierced with a brass pin will have the same effect, while in Brazil a person carrying the hearts of a bat, a frog, and a black hen will become invisible.

Bat magic can also be an antidote to sleepiness. In both ancient Greece and Rome, it was believed that you could prevent sleep either if you placed the engraved figure of a bat under your pillow, or if you tied the head of a bat in a black bag and laid it near your left arm. In many parts of Europe, a practice said to ensure not only wakefulness, but also to protect livestock and prevent misfortune is to nail live bats head down above doorways. Not for the faint of heart, this practice was reported as recently as 1922 in Sussex, England and may indeed continue today.

Canadian Indians relate that bat “medicine” can also bring about the opposite effect of staying awake; traditions claim that placing the head or dried intestines of a bat in an infant’s cradle will cause the baby to sleep all day. In a similar vein, Mescalero Apaches believe that the skin of a bat attached to the head of a cradle will protect a baby from becoming frightened.

Bats have also been said to induce love or desire. In Roman antiquity, Pliny maintained that a man could stimulate a woman’s desire by placing a clot of bat blood under her pillow. In Texas, one lovesick suitor was told to place a bat on an anthill until all its flesh was removed, wear its “wishbone” around his neck, pulverize the remaining bones, mix them with vodka, and give the drink to his beloved. A similar love potion from Europe recommends mixing dried, powdered bat in the woman’s beer.

Bat hearts or bones are often carried as good luck charms. Variations on a belief that apparently began in Germany, and have been repeated in the United States, predict that bats bring good luck at cards or lotteries. The prescription is to wrap a bat’s heart in a silk handkerchief or red ribbon and keep it in a wallet or pocket, or tie it to the hand used for dealing cards. Some also believe that tying a silk string around a bat’s heart will bring money.

Another superstition from Germany relates that bullets from a gun swabbed with a bat’s heart will always hit their target. According to the Egyptian Secrets, attributed to Albertus Magnus in the 13th century, mixing lead shot with the heart or liver of a bat will have the same result. Some American Ozark pioneers had another variation of this belief: they carried the dried, powdered hearts of bats to protect them from being shot and to keep wounded men from bleeding to death.

It is common in folklore that the desired effect of a potion or medicinal preparation reflects real or imagined characteristics of the ingredients. (We’ve heard about cannibals eating the heart of a valiant but vanquished foe to obtain the foe’s courage.) It is also common that the desired effect of a potion can be the opposite of the characteristics perceived in their ingredients. It is easy, therefore, to imagine the motivations for some bat preparations thought to cure various maladies.

Bats and Folk Medicine

Many beliefs in Europe and the United States relate the value of bats’ blood, or their excrement, as a depilatory. But in England and North Carolina the use of bats’ blood has been advocated to prevent baldness. In India, using a hair wash of crushed bat wings in coconut oil is said to prevent both baldness and graying of hair.

Medicinal preparations using bats are legion and have been recommended for many other maladies. Folk healers prescribe a large variety of bat preparations for problems with vision, ranging from dimness to cataracts. Other bat folk medicines are said to be remedies for snakebite, asthma, tumors, sciatica, fevers, a painless childbirth, or to promote lactation.

Sir Theodore Mayerne, who lived in the 15th century, prescribed “balsam of bat” as an ointment for hypochondriacs, his recipe consisting of “adders, bats, suckling whelps, earthworms, hogs’ grease, stag marrow, and the thigh bone of an ox.” In the 1700s one physician recommended that, properly prepared, the flesh of bat was good for gout.

Folklore from Brazil suggests taking dried, powdered bat as a remedy for epilepsy. In more modern times, Texas folklore advocates drinking bat blood to cure rheumatism and consumption, and asserts that rubbing warts with a bat’s left eye will remove them.

Many of the folk remedies and magical properties ascribed to bats are directly related to their physical features and lifestyles. Wakefulness at night or sleeping all day are well-known characteristics of bats. Although none are blind (except by injury or congenital defect) and most have good vision, “blind as a bat” is still a commonly heard phrase, and many people believe it. But before the discovery in the 1930s that most bats use echolocation to navigate both at night and in total darkness, many people were convinced that bats not only had excellent vision, but that they could actually see in the dark. The use of bats to treat ailments of vision is therefore not surprising.

The extensive folk association of bats with hair can likewise explain their use as a depilatory or for preventing baldness. A less likely possibility is that bats are believed to promote lactation because, for their size, lactating female bats can produce a truly prodigious supply of milk for their young. Perhaps even more fanciful is that the 18th century doctor might have imagined bats to be a remedy for gout because they rest with their feet above their heads. In colonial North Carolina, eating roast bat was a recommended cure for children who ate dirt.

Lucky Bats

The Chinese believe that bats are a symbol of long life and happiness. In China, the ideogram for good luck, “fu” sounds the same as the word for “bat” and so the animal is a lucky charm.

To see five bats at once represents the Five Happinesses:

- Health

- Wealth

- Longevity

- A virtuous life

- A good death.

Like the Taoist Immortals, bats live in caves and so they, too, are symbolic of longevity and immortality. Some bat caves in the East have remained unchanged for thousands of years; the bats that live there are revered as sacred animals.

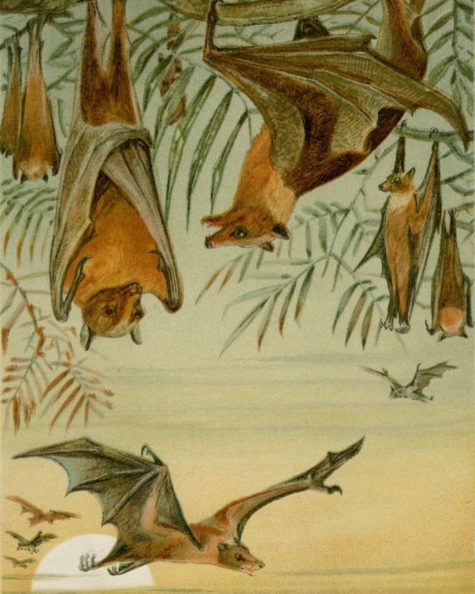

Chinese art is rich with images of bats. Bats fly joyously across fabrics and tapestries, jewelry and porcelain, and are carved into jade and ivory, and adorn the columns and facades of palaces and the thrones of emperors. As symbols of good luck and happiness, bats have few rivals in Chinese culture, and their admiration for bats is ancient.

Bats, thought to embody the male principle, were often depicted with peaches, a popular female fertility symbol. Such designs also hint at acknowledgement of an ecological relationship. Peaches were first cultivated in China some 5,000 years ago, but their wild ancestors relied on bats to disperse their seeds.

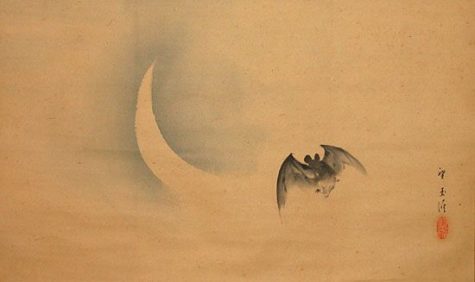

Bats were also very popular in Japanese culture. Under the influence of the Chinese, the bat was viewed as a good-luck symbol, and its image was often used in pottery, sword kilts and kimonos.

In Japanese, the word for “bat” is “Koumori.” There are several possible explanations as to why bats were given this name. One explanation is that it originated from the word “Kawamori,” which means protecting rivers. A second option is that it came from the word “Kawahari,” which means skin is stretched between bones. But it is also logical to believe that it was derived from “Kawahori,” which means eating mosquitoes. Regardless, it is certain that people back in the day did not have a poor image of bats.

The Sacred Flying Foxes of India

To most people in India, especially those in rural areas, bats are not attractive. The exception is the large Indian flying fox (Pteropus giganteus); for many, this bat is considered sacred.

One colony of around 500 Indian flying foxes roosts in a huge banyan tree in the small village of Puliangulam, about 40 miles east of Madurai in southern India. The colony is considered sacred and treated with special care. When a team of researchers from Madurai Kamaraj University visited Puliangulam to talk to the local people about their beliefs concerning the flying foxes, an 80-year-old woman reported that the colony had occupied the tree even before her birth.

According to the villagers, the bats seek protection from a God named Muni who dwells around the tree. They never disturb the bats and do not permit others to do so even when only a glimpse is wanted. Those who do not heed the protests of the protective villagers may find themselves in an adamant quarrel; if a villager fails to protect the bats, even in circumstances beyond their control, they believe Muni will punish them.

Punishment can be rendered in the form of a business loss, an accident, or can be as severe as a death in the family. Those who are punished approach the God and seek forgiveness by offering prayer and “pooja,” a customary ceremony (after “pooja,” sweet rice, coconut and banana is distributed to those in attendance). The villagers say that about eight such cases have happened. But while the live flying foxes must be protected at all costs, freshly dead bats found on the ground are taken for food, but only after prayers are offered to Muni.

Indian flying foxes are considered sacred in a few other villages in southern India, and several in northern India as well. Even though some populations of these flying foxes are protected because of their sacred status, bats in unprotected colonies are killed as a source of protein and also because they are thought to possess medical powers.

Origin Stories About Bats

Throughout the world, folklore is rich with tales speculating on how creatures as mysterious as bats came to be.

People often perceive bats as anomalous or ambiguous creatures, different from more “normal” animals. They have fur and teeth and nurse their young like other mammals, but they don’t walk on four legs. They have wings and fly like birds (actually, in many ways better than birds). They live in unusual places. Most often, they are seen only at night. What are they?

In the terminology of folklorists, bats are “liminal”; they don’t fit into the normal order of things and are somehow apart or in-between. This apparent ambiguity in the nature of bats is seen in many folktales about how they came to be in the first place and how they acquired their various features.

The origin of bats is prominent in the folklore of several North American Indian tribes. Here’s a Cherokee fable:

An eagle, a hawk, and other birds fashioned the first bat and the first flying squirrel from two mouse-like creatures. These small creatures wished to participate in a ball game in which the “animals” challenged the birds.

Because they were four-footed, the mouse-like creatures first asked if they could play with the animals, which included a bear, a deer, and a terrapin. But the larger animals made fun of how small the creatures were and drove them away.

They then appealed to the eagle, the captain of the bird team. The birds took pity on the creatures and fashioned wings for one of them out of the head of a drum made from a groundhog skin, thus creating the first bat. Because not enough leather remained to fashion another bat, the birds then stretched the skin between the fore and hind limbs of the other creature, making the first flying squirrel.

With the help of the bat and the flying squirrel, the birds won the ball game, with the agile bat scoring the winning goal.

In a Creek Indian variation of this tale, the bat first asks to play with the birds but is rejected by them and accepted by the animals’ team. The animals then give teeth to the bat to make it more animal-like. Using its new teeth to hold the ball, the bat helps the animals to win the game.

Apaches tell a different tale about bats:

Jonayaiyin, a hero who battled the enemies of mankind, killed several eagles and gave their feathers to a bat who had helped him escape from the eagles’ nest. Repeatedly, the bat’s feathers were stolen by small birds, and repeatedly the bat returned to Jonayaiyin to ask for more. Frustrated, Jonayaiyin eventually told the bat “You cannot take care of your feathers, so you shall never have any.” “Very well,” said the bat, “I deserve to lose them, for I could never take care of those feathers.”

Traditional Navajo folklore places the origin of bats in the earliest world, when all was dark: twelve insects and the bat revolved in darkness. The bat serves as mentor of the night and is identified with Talking God, one of the foremost deities.

Pomo Indians of California have a myth that a bat could chew and swallow a large piece of obsidian and then vomit large numbers of excellent arrowheads.

Folklore from Fiji, in the South Pacific, tells us that flying foxes originated when a rat stole the wings of a heron, while another Fijian tale relates that it was the rat that first had wings while flying foxes walked on four legs. The flying fox obtained his wings when he borrowed them from the rat and refused to return them. The rat now tries to retaliate by climbing tees and eating the flying foxes’ young, and this is why flying foxes carry their pups with them. Samoan folklore tells of a similar origin for bats.

A modern variation of the myth that bats arose from rodents comes from an Ohio woman of Polish ancestry who attested that “the bat was from a mouse that had eaten blessed Easter food.” (In Polish tradition, a representative food from the Easter dinner is taken to church to be blessed.)

Christianity and the origin of bats are also intertwined in the Mohammedan legend that Christ created a bat while keeping the fast of Ramadan. During this time eating food between sunrise and sunset is forbidden. Because mountains obscured the western sky, Jesus could not tell when the sun set. With God’s permission, He fashioned the winged likeness of a bat from clay and breathed life into it. The bat flew to a nearby cave, but each evening it emerged at sunset, telling Jesus that it was time to take food.

The apparent liminality of bats is also reflected in a legend from the Kanarese of India in which bats were originally a type of unhappy bird. These birds went to temples and prayed to be turned into humans. Their prayers were answered, but only in part; they were given teeth, hair, and human faces, but otherwise remained bird-like. They were then ashamed to meet the other birds and are now active only at night, returning to the temples in the daytime and praying to be turned back into birds.

In several other folktales, bats are banished into the night either as a result of some treachery or, as in the case of the Kanarese, because of embarrassment resulting from ill-advised behavior. In two fables from Aesop (born ca. 620 B.C.), the ambiguous nature of bats is transformed into duplicity in their character.

One of these fables also exists, with slight variation, among tribes in southern Nigeria, among Australian aboriginals, and ancient Romans. The basic scenario is that, in a battle between the beasts and birds, the bat repeatedly changes allegiance so as to be on the side that appears to be winning. When a truce is declared, the bat is rejected by both sides because of this deceitful behavior.

In another tale from Aesop, a bat borrows money for a business venture that fails. The bat must then hide during the day to avoid creditors. Greeks and Romans often referred to people who were active at night as “bats.” Apparently many of these people had adopted nocturnal behavior to avoid those to whom they owed money.

The Greek philosopher Chaerephon was called “the bat,” because he, like the animal, did not appear by day but instead hid and philosophized.

American Indian legends and the fables of Aesop were more than just stories recited around the campfire or bathhouse: they were teaching devices. For American Indians they provided information on the natural world and the behavior and habits of animals. Many of these myths have obvious roots in the real features of bats. Their well-known agility in flight would make a bat formidable in a ball game against a bear and turtle. The lack of feathers, presence of teeth, and activity at night are rooted in basic biology and natural history.

A general theme in American Indian folklore is that, in the beginning, there were no essential differences between humans and animals. Until we provoked the animals’ hostility because of our aggressiveness and disregard for their rights, humans and all creatures lived together in harmony, mutual respect, and helpfulness. Thereafter, humans and animals may have lived different lives; but like people, the animals still had tribes, councils, and ethics, and they played ball games.

The natural characteristics of bats provide a rich foundation for symbolism, making them creatures of life and death, fecundity and destruction. For the ancients, human sacrifice, in which the bat participated symbolically, nourished the sun and the gods of nature. The bat is part of a vital chain–both in nature and in myth–and some peoples, whose environment the bat shares, identify with its symbolic power.

More Bat Mythology

The people of ancient cultures venerated creatures who, to them, symbolized anomaly and transformation. The bat is one of these. For many cultures, it was–and is still–a kind of intermediary to the gods, partly because of its uniqueness, partly because it fits into, and contributes to, man’s environment.

A Toba story from the Gran Chaco region of northern Argentina tells of the leader of the very first people–a hero bat or bat-man who taught people all they needed to know as human beings. And from the Ge in Brazil comes a tale of a tribe that moved through the night led by a bat who looked for light toward which to guide them.

The Native American animal symbolism of the bat comes from a keen observation of this magnificent animal. These people recognized that the bat was highly sensitive to their surroundings and so therefore was considered a symbol of intuition, dreaming and vision. This made the bat a powerful symbol for Native American shamans and medicine people. Often the spirit of the bat would be invoked when special energy was needed, like “night-sight” which is the ability to see through illusion or ambiguity and dive straight to the truth of matters.

For Arawak Indians in northern Guiana, Bat Mountain is the home of “killer bats,” and there also is a killer bat in folklore from Venezuela. Decapitating bat demons appear in various myths in the Amazon region, and, to the south, in the Gran Chaco of northern Argentina.

Folklore from the Ge tribe in Brazil tells of “Indians” who had wings and bat noses, lived in a big cave near a river, and went out only at night. Flying like bats, they killed with “anchor axes” or “moon hatchets.” In another tale, mankind acquired ceremonial axes from bats who had used them for decapitation. The shape of the axes is the same as the sacrificial knives most often depicted in ancient Mochica art far away in the Central Andes.

Much of this bat sacrificial symbolism likely derives from the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus), a very small creature that feeds entirely on the blood of vertebrates. Although they may bite various parts of the body of their prey, they normally feed from the neck and shoulder regions of large mammals, a behavior that may have fostered tales of decapitating bats.

Another bat, whose habits also may have contributed to such legends, is the false vampire (Vampyrum spectrum). With a wingspan of almost a yard, the false vampire is the largest New World bat. It is a carnivore, eating birds and other vertebrates, even occasionally eating other species of bats. When capturing its prey, it grabs the neck, sometimes killing with a single, powerful bite.

Some folklore portrays female bats as alluring to men. One tale tells of a man summoned by bats in a tree when he was returning from an evening hunt. He went to have a drink with them and became attracted to a female bat. Night after night, the man stopped off to drink and flirt with her, slowly developing a bat’s head, claws, and “little nose patches.” Finally, his wife, aware of what was happening, set fire to the tree and killed both her husband and the bats. In other stories, bats are husbands in folktales, although often the wife does not realize at first that she is married to a bat.

Tobacco and Bats

Tobacco is an important ritual plant in many places. Both bats and tobacco are associated with shamans (native priests). The Bororo, a tribe in Brazil, tell a story about men casually smoking one night. A vampire bat flew by and told them that, if they did not smoke reverently, they would be punished, “because this tobacco is mine.” According to the story, the men who disobeyed the bat were turned into otters.

Another aspect of the tobacco relationship is the fact that fire often occurs with bats in folklore (although it may also derive from observing large numbers of bats emerging from a cave at twilight, often appearing like a great cloud of smoke). In folk tales, supernatural bats often burn their victims or they are themselves destroyed by fire. In addition, natural fires in caves sometimes occur from spontaneous combustion of bat guano.

The Bat in Navajo Lore

Several North American Indian tribes include bats in their traditional folklore. For the Navajo, the bat holds a special significance.

For the traditional Navajo Indian in the deserts of the American Southwest, the bat is an intermediary to the divine, bridging the supernatural distance between men and gods. Bat serves as mentor of the night, as Big Fly does by day. Bat’s origins are given as within the earliest world, when all was dark: twelve insects and the bat revolve in blackness.

Both Bat and Big Fly are part of the Sun-Sky complex and stand for the skin at the tip of the tongue: speech. As Sun’s day and night messengers, they are identified with Talking God, one of the foremost deities. Both have the ability to penetrate where ordinary beings cannot go.

They are not gods, though, in that they do not require an offering or payment, but instead volunteer their aid. One Navajo chant describes a scene at the hogan (a traditional Navajo dwelling) of the female deity, Changing Woman. When she begged the great gods to carry an offering to Winter Thunder, everyone was afraid until finally, after much coaxing, Bat, who occupied the humblest seat near the door, consented to go.

Mentors are ever present, although sometimes invisible. At traditional Navajo assemblies, if after four nights of discussion no constructive plan has been achieved, a voice from near the door or from some concealed place in the ceiling gives a clue to the proper offering and the god to whom it should be presented. The suggestion can be obscure, but furnishes enough information to be understood with concentration.

Eventually, the voice “appears,” embodied as Bat or Big Fly (or as Wind or Darkness) and introduces itself as a guardian of the home of some powerful supernatural being, all of whose secrets it knows. Many times a seeker achieves his quest because whispered messages in his ear inform him of the necessary directions to perform.

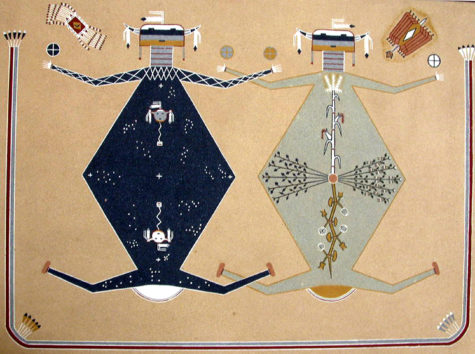

In Navajo sand paintings, a traditional and ceremonial art form, brown sands form Bat, and its station is as one of the eastern guardians. A yellow diamond on its body represents a small skin that Bat received as a reward for helping depose the Gambler (a large and powerful deity).

The sand painting, “Father Sky and Mother Earth,” is a paradigm of Navajo beliefs. Father Sky and Mother Earth were the first creations of the Great Spirit. Their crossed hands signify the union of heaven and earth, bound eternally together by the Rainbow Guardian. In all directions, sky and earth are fused as one on the horizon. The physical earth and sky, or mind (spirit), functions together to produce new life.

All things are conceived first in thought before they become physical reality, represented by the line running from the head of Father Sky to the head of Mother Earth. Physical pain, disease, or “evil” was first conceived in thought before it appeared in the body. To cure sickness, a poor crop, or whatever the need, one must first establish a harmonious rhythm with all unknown forces.

The stars, moon, and constellations are shown on the body of Father Sky, the zig-zags crossing his shoulders, arms, and legs forming the Milky Way. The life-giving energy of the sun radiates from the bosom of Mother Earth, bringing fertility to her womb, from where the seed of all living things springs.

Bat, the sacred messenger of the spirit of the night, guards the sand painting at the opening in its border.

Bats and the Netherworld

The nocturnal habits of bats have no doubt contributed to the many myths that bats are creatures of another, unearthly world.

Since antiquity, people have perceived many of the physical features of bats as strangely similar to those of humans. And the pointed ears of bats, their sharp teeth, leaf noses, wart-like protuberances on their chins, and their leathery wings supported by the same bones that are in the arms and hands of humans, have long led the superstitious to imagine that bats are merely a grotesque parody of the human form.

The persistent association of bats with the supernatural and the idea that they inhabit a world related to, but beyond, our existence undoubtedly also derives from the habits of bats. Bats are active at night while people sleep, and many bats spend their days in caves, abandoned buildings, church steeples, and tombs.

One common folk belief is that bats are human souls that have left the body. Contemporary Finnish folklore relates that during sleep, the soul leaves the body and may appear as a bat. Such lore also explains the disappearance of bats during the day, since when humans awake, their souls return home to their bodies. In his 1939 book Bats, G.M. Allen reports testimony on the validity of this belief from an aged Finn who related an example where, upon awakening, a man could remember the places he had visited as a bat the night before.

When seen as human souls, bats are often imagined as souls of the dead, particularly souls of the damned, or those that are not yet at peace. Both African-Americans and those of European descent from around the United States frequently maintain that bats are “ghosts” or “haunts.” Sicilian peasants relate that the souls of persons who meet a violent death must spend a period of time, determined by God, as either a bat, lizard, or other reptile. In the Auguries of Innocence, William Blake saw the bat as the damned soul of the infidel:

The bat that flits at close of eve

Has left the brain that won’t believe.

An even earlier example of Western tradition associating bats with souls of the damned is provided by Homer when Hermes conducts squeaking, bat-like souls to Hades (The Odyssey, XXIV, 5-10). In Greek mythology, the bat was said to be sacred to Proserpina, the wife of Pluto, ruler of the underworld.

There is also long tradition associating bats directly with the devil and evil spirits. In medieval Europe, artists typically represented devils with bat-like wings and pointed ears. Gustave Doré’s illustrations for Dante’s Inferno followed the tradition of portraying good spirits with the wings of birds and evil spirits with the wings of bats.

Similarly, the Mayas of Central America had a bat God, Cama-Zotz (or “death bat”), depicted as a man with bat wings and a bat-like leaf nose, who lived in a region of darkness through which a dying man had to pass on his way to the netherworld.

The association of bats with the devil continues today in many cultures. An African-American folk legend relates that the devil may appear as a bat. In Ohio in 1962, a student nurse of eastern European extraction related that “bats are the devil in bat form.” A contemporary Mexican belief is that bats are diablos (devils) from hell. Such lore is encountered today in the common expression “like a bat out of hell” (which even made it into contemporary music as a title by rock musician Meatloaf).

If not the devil itself, the bat is frequently seen as helping the devil in its work. This is evidenced by the frequent associations of bats with witchcraft. A Russian legend repeated by G.M. Allen relates that Satan wished to create a man, and after fashioning a human form from mud, could not give it life. Satan then enlisted the aid of the bat to fly to heaven and steal God’s sacred “towel,” which would give Satan’s creation a divine nature. The bat complied, and according to the legend this is why God owns man’s soul and Satan his body. God punished the bat for helping Satan by taking away its wings (presumably its feathers), making its tail naked, and fashioning its feet like those of Satan.

There is also persistent folklore repeated in many parts of the United States in which the bat is said to be the “child” or a creation of the devil. German devil myths include tales about how the devil attempts to imitate the creations of God, but never quite gets it right. God creates a bird; the devil attempts to imitate God’s creation, but ends up with a bat. God makes man; the devil, apes, and so on.

Some ancient allegories about the bat even made it to the Bible. The bat is reckoned among the birds in the list of unclean animals, and to cast idols to the ‘moles and to the bats’ means to carry them into dark caverns or desolate places to which these animals resort (Isaiah 2:20), i.e., to consign them to desolation or ruin.

In a complete reversal of this creation myth, a Mohammedan legend relates that the bat was created by Christ. In this myth Jesus was in the desert outside of Jerusalem attempting to keep the fast of Ramadan, which forbids eating food between sunrise and sunset. Because mountains obscured the western sky, Jesus could not tell when the sun sank below the horizon. With God’s permission, Jesus fashioned the winged likeness of a bat from clay and breathed life into it. The bat quickly flew to a nearby cave, but each evening it emerged at sunset, which told Jesus that it was time to take food.

Vampires and Bats

Perhaps the most persistent and damaging association with bats is the vampire myth. Vampire bats do, indeed, exist, but they total just three species (out of more than 1,100 bat species worldwide). They live only in Latin America and feed primarily on birds (two of the vampire species) or mammals, especially livestock.

Vampire bats have never been found in Europe, and it is not clear when news of the New World vampires reached Europe. Some say the early explorers of the Americas brought news of these bats back to the Old World in the 1550’s, while others doubt that word of their existence reached The Continent until the early 19th century.

Vampire myths existed long before Europeans or the rest of the Old World ever knew of the existence of bats that fed on blood. The word “vampire” came from the Slavic vampir, meaning “blood-drunkenness,” but the mythic creatures have been called by many names. Legends of the undead abound with many variations throughout most of the world. Some of the earliest came from Babylonia: The edimmu was a troubled soul who wandered the earth in search of human victims whose veins it sucked. Many cultures had similar legends–the Greeks, Arabs, the gypsy cult in India, even the ancient Chinese.

In Europe, vampires inspired great fear and, sometimes, mass hysteria. In an attempt to explain the cause of epidemics, which often decimated entire villages, vampires frequently were blamed. Some of the strongest beliefs came from peasant tales in what is now Hungary and Romania in Eastern Europe, and the legends with which we are familiar today came largely from these. With them originated the belief that the vampire entity could leave its body at will and travel about as an animal or even as flame or smoke. Interestingly enough, bats don’t appear traditionally to have been one of those transformations.

As creatures of the night, bats had long been associated with witchcraft and demons in European traditions, both in fable and art. But most accounts agree that it wasn’t until Bram Stoker wrote his classic novel, Dracula, in 1897 that bats were linked with vampires for the first time. The seeds were planted for much of the intense fear people today have toward all bats and have been exploited ever since. Who can forget the scene from the 1931 film, Dracula, in which the elegant count, immortalized by Hungarian actor, Bela Lugosi, stands before an open balcony door, spreads his dark cape and silently takes flight, transformed into a small bat flying against the full moon?

In either case, the fact remains that the vampires of folklore have nothing to do with bats. Vampires were described in legend as dead humans with the ability to rise from the grave, always at night. They appeared sometimes in the guise of an animal, usually a wolf, and sometimes they were invisible. They were never in the form of a bat. These revenants, as they are properly termed, supposedly cause all sorts of trouble and strife; they have been blamed for illness, epidemics, plague and pestilence.

While some vampires of folklore suck blood from their victims, many do not, which immediately differentiates them from the vampires of literature, where blood sucking is an absolute necessity. Folklore’s vampires bite at the chest, while fiction’s vampires go for the neck.

Although bats have been linked to the mysterious and magical for centuries, their association with vampires is the result of an Irish writer. Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula was published in London in 1897. The villain of the piece is one Count Dracula, based on the disreputable Prince Vlad of Transylvania. Dracula apparently was Vlad’s nickname, meaning something on the order of “devil.”

Stoker created his Dracula as a vampire, thus giving rise to the vampire of fiction (with so little in common with those of folklore). Stoker seems to have been the first to depict a vampire as taking the appearance of a bat. Stoker may have been influenced by the vampire bats of Latin America, since their existence was well known in Europe by that time.

The first of many movies based on Stoker’s Dracula was made in Germany in 1922. Called Nosferatu and directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, it is arguably the most influential horror film ever made. The bad guys of Murnau’s movie are not bats but rats. Hollywood took over in 1931, with the movie Dracula, starring Bela Lugosi. Here, the connection between bats and vampires was cemented, and it has remained so ever since.

The word “vampire” is almost certainly of Slavic origin, probably from the Old Slavic word o,pyr, meaning “spectre.” It became vampir when it moved into Western European languages, and returned to Slavic in that form. The true Slavic word for vampire, volkodlak, means “a person in the guise of a wolf.”

The damaging links between the bats and vampires are clearly very recent and without basis in folklore. Bram Stoker’s contribution did a disservice to both bats and vampires. With little historic or folkloric basis for a fear of bats, this fictional link with vampires may well be a key source of the still-frequent revulsion for these gentle mammals.

Bat Names and Linguistics

Bat, bat, come under my hat

and I’ll give you a piece of bacon …

~English nursery rhyme

Thank the Vikings. The fearsome Norsemen who terrified, raided and eventually settled parts of England apparently gave us the Swedish bakka and Danish baake, words that the centuries turned into the English “bat.” But the old Scandinavian words mean “bacon.” What’s going on here?

Bats and bacon are entwined as well in parts of Germany, where the word for bat is Speckmaus, literally “bacon mouse.” This has nothing to do with bats as a side dish for eggs. Rather, I believe, it traces to the way flitches (sides) of bacon were hung on hooks from the ceiling of smokehouses. Bats hanging upside down in a roost likely looked somewhat similar.

Here’s an abbreviated list of the “standard” words for bat in various European languages. The translations are literal and based on the etymology of the native word.

- Albanian: naked owl

- Basque: old mouse

- Breton: blind mouse; skin wing

- Bulgarian: the one who sticks, adheres to

- Catalan: feathered mouse; blind mouse

- Croatian: blind mouse

- Danish: flutter mouse

- Dutch: flutter mouse

- English: moving mouse; air mouse; flutter mouse

- Estonian: leather mouse

- Finnish: the fluttering one; wing-footed one

- Flemish: flutter mouse

- French: bald mouse (or possibly owl mouse)

- Gaelic: evening mouse

- German: flutter mouse

- Greek: the night one

- Hungarian: leather mouse; winged mouse

- Icelandic: leather rag

- Ingrian: night flutterer

- Italian: little evening one; hand wing

- Karelian: night flutterer

- Irish: leather wing

- Latin: the little evening one

- Latvian: leather wing

- Livonian: leather wing

- Norwegian: flutter mouse

- Portuguese: blind mouse

- Rhaeto-Romanic: night flyer

- Russian: flying mouse; the leather one

- Serbian: blind mouse

- Spanish: blind mouse

- Swedish: flutter mouse

- Ukrainian: the leather one

- Votian: night flutterer

- Welsh: a flitch of bacon

- Yiddish: flutter mouse

Sources:

- Amanda Gatlin

- Element Encyclopedia of Secret Signs and Symbols

- BATS Magazine

Abracadabra

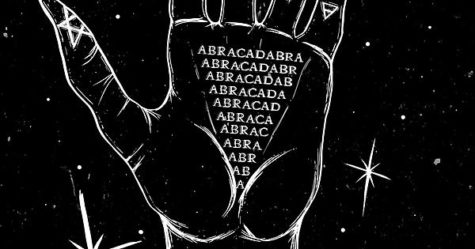

Nowadays, “abracadabra” is a word used by stage conjurers when performing their magic. However it has a lengthy history as a protective amulet and lucky charm.

This word is extremely ancient and originally was thought to be a powerful invocation with mystical powers. This ancient word may well have been inspired by the Aramaic: “Avra Kedabra” which means, “I create as I speak” or words to that effect. Its origin is unknown, but Cabalists were using it in the second century CE to ward off evil spirits.

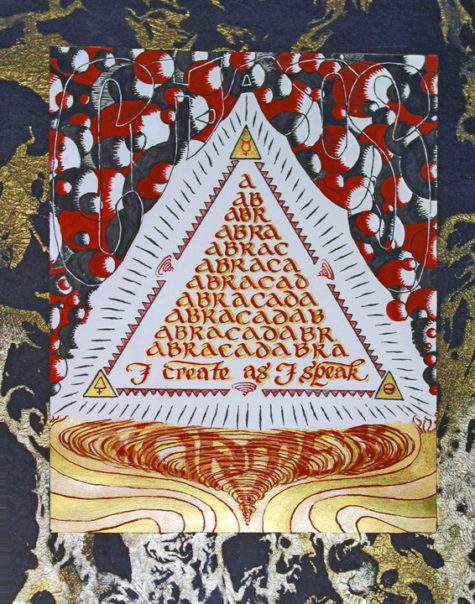

It is most often used magickally as a charm, and written as a triangular formula:

A B R A C A D A B R A

A B R A C A D A B R

A B R A C A D A B

A B R A C A D A

A B R A C A D

A B R A C A

A B R A C

A B R A

A B R

A B

A

In the Middle Ages, many people believed wearing parchment amulets with the word “abracadabra” written in the form of an upside-down pyramid would cure fevers, toothache, warts, and a variety of other ailments. It would also protect the wearer from bad luck. The word was written eleven times, dropping one letter each time.

Sometimes letters would be sequentially removed from each end of each line, making for a shortened version consisting of just six lines.

The idea was that as the word vanished, so would the fever. An amulet of this sort was attached to linen thread and worn around the neck. It was usually worn for nine days and then discarded.

The best way to do this was to toss it backwards over your left shoulder before sunrise into a stream that flows from west to east. The reason for this s that the left side was believed to be related to the devil. Tossing the amulet into a river that flowed in the direction of the rising sun symbolically banished the evil, and replaced it with the good created by the rising sun that banishes darkness.

Daniel Defoe wrote about these charms in his Journal of the Plague Year (1722), saying that they were worn to protect people from the plague.

Even saying the word “abracadabra” out loud was believed to summon powerful supernatural forces. This is probably why magical entertainers still use it as a magic spell today.

It does matter which direction the Abracadabra is pointed. Pointed downwards, it will help you to rid yourself of evil and misfortune, when pointed upwards, it will bring good fortune.

It was first recorded in a Latin medical poem, De medicina praecepta, by the Roman physician Quintus Serenus Sammonicus in the second century AD. Serenus Sammonicus said that to get well a sick person should wear an amulet around the neck, a piece of parchment inscribed with a triangular formula derived from the word, which acts like a funnel to drive the sickness out of the body.

Theories about the origin of this word are as follows:

It was derived from the Hebrew phrase “Abreq Ad Habra” meaning “Hurl your thunderbolt unto death” or “Strike dead with thy lightning;”and is associated with a thunderbolt deity who perished by throwing himself on the planet so that the creatures of earth could live. In this case its efficacy as a charm to ward away illness would make sense.

It originated with a Gnostic sect in Alexandria called the Basilidians and was probably based on Abrasax, the name of their supreme deity (Abraxas in Latin sources).

It may have come into English via French and Latin from a Greek word abrasadabra (the change from s to c seems to have been through a confused transliteration of the Greek).

It could be from the Aramaic “Abhadda Kedabhra” meaning “Disappear as this word,” which accurately reflects exactly what happens in the charm. As the word diminishes and finally disappears, so would any malevolent energy.

The first letters of the word could be derived from the initials of Hebrew words for Father (Ab), Son (Ben), and Holy Spirit (Ruach Acadsch).

Chances are that this is such a powerful symbol because all of these theories make sense, so it would have universal appeal.

Although most accounts say that the charm was in use until the Middle Ages, there’s curious proof of its efficacy in a small thirteenth-century church in a remote valley in Wales in the U. St. Michael and All Angels Church at Cascob on the edge of the Radnor Forest has an Abracadabra charm engraved on a tablet on one of its walls. In the seventeenth century a local girl, Elizabeth Lloyd, was apparently possessed of evil demons, and this symbol was used to drive them away, along with the astrological symbols that are carved below. There’s even a possibility that this tablet was made by the alchemist Sir John Dee, who was an astrologer to Queen Elizabeth 1, and lived nearby.

Fans of the Harry Potter books will know the killing curse, Avada Kedavra, in which J K Rowling seems to have combined the Aramaic source of abracadabra with the Latin cadaver, a dead body.

Sources:

- The Element Encyclopedia of Secret Signs and Symbols

- The Encyclopedia of Superstitions