Trivia

The lowest form of accommodation in Victorian England was a place on a rope. For just a penny, you were given access to a rope strung from wall to wall, and allowed to sleep bent over the rope for the night. Usually used by drunken sailors who had spent all their money drinking and now had no place to go to sleep it off. It is said to be the origin of the term “hungover.”

When traveling through the Vermont countryside, especially in the northern parts of the state, you might notice some old farmhouse windows oriented at an odd angle.

Devin Colman, who works for Vermont’s Division for Historic Preservation, says there’s superstitious lore behind the name, “witch window.”

“The story is that a witch on a broomstick can’t fly through a crooked window opening, which I guess physically is true,” says Colman.“But, it’s the only crooked window in the whole house. And if I were a witch, I would just use one of the other vertical windows,” he adds with a laugh.

These 19th-century architectural anomalies, also known simply as “Vermont windows,” or “lazy windows” have blurred origins. Colman says there’s another theory that doesn’t quite add up.

“You’ll also hear them referred to as coffin windows,” he says. “The idea being that it’s difficult to maneuver a coffin with a body from the second floor down to the first floor in these narrow staircases, so slide it out through the window and down the roof — which does not seem any easier. And, if you think about it, you wouldn’t carry a coffin upstairs to put a body in it. You would bring the body downstairs and put it in the coffin on the first floor. So, I don’t think that holds a lot of truth there.”

Britta Tonn is an architectural historian in the Burlington area, and she’s skeptical about that origin story, too. But she’s willing to concede it might be “another convenient use of the window once it was developed.”

“I think they’re just a really great piece of vernacular Vermont architecture that really kind of points to how unique Vermont is and how resourceful farmers were,” says Tonn.

Colman says the real origin of the witch window is probably much less interesting:

“My interpretation as an architectural historian is that it’s simply a really practical New England response to the need to get daylight and fresh air into a second-story room.”

From today’s perspective, it’s clear that there’s a much less mystical explanation for the curious slanted windows: frugality. The sloped windows were the most practical way of getting enough sunlight and fresh air inside the second floor rooms. The windows are usually wedged under the eaves right between the main building and an added wing of the house.

During the 19th century northern Vermont was very rural and dominated by small farming communities with limited or nonexistent access to things like factory-made mill work. If you were building a new house, you trekked to a hardware store and ordered things like moldings, factory-built mantles, and windows from a catalog. The selections were limited and the best you could hope for was to find a premade and glazed window with a width that allowed you to fit the odd sloping space, which was a much better solution than trying to build something on your own. Vermont farmers have always been recognized for their common sense and ingenuity. It’s likely they also reused windows that didn’t fit above the new gable, so were installed at a diagonal to take full advantage of the sliver of available wall space.

Sources: Atlas Obscura and Vermont Public Radio

When Jonathan the tortoise decides to stretch his neck and limbs out of his shell and enjoy a little sunbathing on the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, it’s a sight so peculiar that alarmed passersby will report that the poor creature has died.

That may sound like a rash conclusion, but people have reason to be concerned. At 187 years old, Jonathan is believed to have far exceeded the typical 150-year lifespan of his species to become the world’s oldest living land animal.

The title has been recognized by Guinness World Records, which recently profiled Jonathan. With an estimated birth year of 1832, the affable reptile has lived through the terms of 39 U.S. presidents, two world wars, and the invention of the light bulb. He came to Saint Helena around 1882, with his age at the time figured to be around 50 years old. He was intended to be a gift to the governor of the Overseas British Territory at the time, William Grey-Wilson, and has lived on the grounds of the governor’s mansion ever since.

Advancing age is not without its consequences. Jonathan is nearly blind from cataracts and appears to have lost his sense of smell. He’s cared for by veterinarians who arrange for a nutritious fruit and vegetable diet.

Believed to be a rare Seychelles giant tortoise, Jonathan shares the property with three other shelled friends: David, Emma, and Fred. If he hangs on for a bit longer, he’ll likely set the all-time Guinness World Record for a chelonian lifespan currently held by Tu’i Malila, a tortoise who passed at age 188 in 1965.

From all indications, it appears Jonathan has not lost his taste for life’s pleasures. According to island residents, he’s fond of copulating with Emma and has even been known to enjoy dalliances with Fred. This poses a unique duty for Governor Lisa Phillips, who sometimes has to head outside and put the tortoises back on their feet if they fall off during their sensual encounters.

“That wasn’t in the job description when I became governor,” Phillips said in 2017.

Source: Mental Floss

Vultures are scavenging birds that do our environment a world of good. If you’re not a fan already, we hope these astonishing facts will help you learn to love them.

- There is a Vulture Awareness Day

As a result of the threats that vultures face, the first Saturday of September is now dedicated to celebrating International Vulture Awareness Day. These days are extremely valuable in educating people about the true nature of these vulnerable animals, whilst allowing them to partake in fun activities at the same time.

- Vultures are the sacred bird of Tibet

Tibetan sacred bird, the vulture, falls mainly into the category of the bearded vultures, the largest scavenger birds in Eurasia. As vultures do not usually prey on living animals and instead live by the body of dead living beings, they are considered to be sacred.

Vultures play important roles in Tibetan festivals known as Sky-Burial. The involvement of the vultures in this unique and exotic Tibetan festival includes the popular belief of reincarnation and after life after death.

In the festival of Sky Burial, a human corpse is offered to the vultures. The corpse is placed on the mountain tops, near the abodes of the vultures, indirectly luring them to feed on the corpse and provide the soul of the dead person a chance of rebirth, according to the popular Tibetan belief. According to the Tibetans, the vultures are the disguised ‘Dakinis’. To the Tibetans, Dakinis are angels; hence offerings to the angels are thought to be the sacred way of the end of one life. Dakinis will take the soul into the heavens, which is understood to be a windy place where souls await reincarnation into their next lives.

- Groups of vultures have many different descriptive names.

Interestingly enough, vultures are noteworthy for the fact that they have a very large number of collective nouns, which vary according to their behavior at any given time!

Vultures circling overhead, riding thermals as they search for carcasses are called a ‘kettle’. A group of vultures perched in a tree, meanwhile, are called a ‘committee’, a ‘venue’ or even a ‘volt’. Then, when the vultures descend to the ground to feed on a carcass they’re called a ‘wake’ which we think is beautifully descriptive. This makes a total of five collective nouns for a single type of animal, which is quite exceptional!

- Vultures are divided into two major groups which are not closely related.

With the exception of Australia and Antarctica, every continent has a resident vulture population. Ornithologists split the 23 living species into Old World vultures and the New World vultures (condors belong to the latter). Genetic evidence tells us that these birds aren’t close relatives; they independently evolved similar-looking physiques in response to environmental forces, a rare case of convergent evolution.

Old World vultures, native to Europe, Africa, and Asia, have strongly curved, eagle-like beaks and they can easily grasp things with their hooked talons. By comparison, the beaks on New World vultures, which live in the Americas, are weaker—and these birds aren’t as adept at using their feet to manipulate objects.

- Being bald might help vultures stay cool.

Most vultures, in both hemispheres, have little to no plumage on their necks and heads. Historically, naturalists believed baldness was a sanitary measure, assuming that if vultures had facial feathers, they’d get drenched in blood and gore at mealtime. But it turns out their bald heads may offer another advantage.

Researchers at the University of Glasgow compared photos of griffon vultures in different poses depending on the temperature of their environment. They found that on hot days, the vultures tended to stick their necks out, and in cold weather, they tucked their heads underneath their wings. The scientists concluded that the birds’ bare skin helped them regulate their body temperatures because the skin rapidly loses heat. The trick may come in handy since many vultures have to deal with extreme daily temperature variation in their habitats.

- Vultures poop on themselves for two important reasons.

Much like their bald heads, their unfeathered feet and legs can also help vultures get rid of excess body heat. To aid that process, some species will literally poop on their legs and allow the viscous liquid to evaporate, cooling their skin. The waste serves an additional purpose: Thanks to their diet, vulture poop is highly acidic and acts as a disinfectant for their feet, slaying harmful bacteria they pick up while hopping around animal carcasses.

- John James Audobon instigated a vulture war.

In 1826, John James Audubon challenged the prevailing belief that all vultures had an extraordinary sense of smell. Audubon’s field experiments with birds he believed to be turkey vultures convinced him that the birds used sight to track down their food. Divided over this issue, ornithologists broke off into rival factions: “Nosarians” still believed that vultures were scent-driven animals while “anti-nosarians” agreed with Audubon’s thesis.

Both sides were partially right. Most Old World vultures are indeed guided by vision—as is the North American black vulture, which is probably the species that Audubon looked at in his experiments. But the turkey vulture has a phenomenal sense of smell, allowing it to zero in on carcasses from thousands of feet overhead—a nice compliment to the animal’s keen eyesight.

- The Turkey Vulture doesn’t have a nasal septum.

The nasal septum, a wall of bone and cartilage in the nose, separates the left and right nasal passages. Turkey vultures lack this structure, which is also absent in yellow-headed vultures. If you look at them from the side, it’s possible to see clear through their bills.

Turkey vultures have an extraordinary sense of smell. They have been known to be able to smell carrion from over a mile away which is very unique in the bird world. The turkey vulture has the largest olfactory (smelling) system of all birds.

- Egyptian vultures can use tools.

With round-edged stones, the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) hammers away at ostrich eggs until they crack open. Once the hard work has been done, though, ravens will sometimes swoop down, chase the vultures off, and steal the exposed yolks. That’s life for you.

- To locate food, some vultures follow the crowd.

Old World vultures keep a close eye on their neighbors. When one of the birds locates a carcass, another individual may watch its descent and infer that the first bird is headed towards a dead animal. In short order, a whole bunch of observant vultures can gather around a carcass, simply by following other members of their species. Likewise, some African vultures track steppe and tawny eagles over long distances in the hope that these raptors will lead them to a nice meal of carrion.

- Many cultures have viewed vultures in a positive light.

Given their reputation as scavengers, people often think of vultures as disgusting or unsavory birds. But some cultures admire vultures and their scavenging ways. In ancient Egypt, vultures were thought to be especially devoted mothers, so they were commonly associated with maternity and compassion. Also, since the birds soar at great heights with an all-seeing gaze, the ancient Egyptians viewed them as living embodiments of their rulers.

- The Andean Condor has the largest wing surface of any living bird.

From tip to tip, the wingspan of an Andean condor can measure 10.5 feet across. Although some albatrosses and pelicans can reach longer maximum wingspans, their wings are a lot skinnier than vultures’. The Andean Condor beats them in terms of total surface area.

The Andean Condor is the world’s heaviest soaring bird. Because it flaps its wings for only 1% of the time during flight, this amazing bird can fly 100 miles without flapping its wings.

- Vultures can fly really high.

The Ruppell’s griffon vulture is the world’s highest flying bird. In 1973, one collided with an airplane off the Ivory Coast; at the time, the plane was flying at 37,000 feet.

- Bones comprise most of the Bearded Vulture’s diet.

Using powerful digestive acids, the stomach of a bearded vulture—native to Eurasia and Africa—can break down solid bones within 24 hours. Bones and bone marrow account for 85 percent of the bearded vulture’s diet. To break larger bones into bite-sized fragments, the birds will drop them from heights of 164 to almost 500 feet.

- The Palm-Nut Vulture loves fruit.

A widespread denizen of central and southern Africa, this black and white vulture does consume small animals and carrion. But it’s mostly a vegetarian. The palm-nut vulture’s primary food sources are fruits, grains, and plant husks.

- Turkey Vultures can’t kill their prey.

Turkey vultures are the only scavenger birds that can’t kill their prey. A close inspection of their feet reminds one of a chicken instead of a hawk or an eagle. Their feet are useless for ripping into prey, but the vultures have powerful beaks that can tear through even the toughest cow hide. They feed by thrusting their heads into the body cavities of rotting animals.

- California Condors have made a huge comeback.

Lead poisoning, pesticides, and active persecution have put vultures at serious risk. No fewer than 16 species are classified as endangered, threatened, or vulnerable. Around the world, captive breeding programs are trying to throw the birds a lifeline. Similar efforts have done wonders in the past. In 1982, the global population of California condors consisted of just 23 birds. Now, there are over 400 documented individuals, with more than half of those flying free out in the wild. Although their long-term survival as a species is by no means guaranteed, captive breeding—and increased public interest—helped reverse the condors’ fortunes.

- Vultures barf on their predators.

Vultures have developed ironclad stomachs to be able to consume tough flesh and bones. Their extremely acidic digestive fluids not only break down rotting meat; they also kill pathogens like anthrax, botulinum toxins, and the rabies virus that would otherwise make them sick. Those fluids can also be a handy, highly corrosive weapon against predators. When turkey vultures and other species feel threatened, they upchuck a mess of semi-digested offal and acid toward their attackers and escape. This defensive vomiting may also rid their stomachs of a heavy meal so they can take flight quickly.

- The King Vulture has no eyelashes.

Unlike many New World vultures, the king vulture does not have eyelashes. King vultures grow to about 2.5 feet tall and may get to a weight of 8 pounds, making them the largest New World vulture, except for the condors. Though it appears to dominate over a feeding site, this vulture actually relies on other stronger-beaked carrion-eaters to initially rip open the hide of a carcass.

The fleshy wattle that bulges from the king vulture’s beak is called a ‘caruncle.’ Both males and females sport these facial features, though the wattle’s purpose continues to perplex scientists.

- Without vultures, there’d be a lot of roadkill lying around.

Researchers have estimated that in the Serengeti ecosystem of eastern Africa, vultures devour more animal flesh than all of the region’s carnivorous mammals put together. As nature’s clean-up crew, vultures slow the spread of diseases—including those affecting livestock. And the birds help sustain plants by returning nutrients to the environment.

When vulture populations decline, other scavenging animals won’t always pick up the slack. In 2018, a research team deposited two sets of rabbit carcasses in rural South Carolina, with one set accessible to turkey vultures and the other inaccessible. They waited seven days, and guess what happened? In the vulture-free group, 80 percent of the rabbits were untouched by vertebrate carnivores, showing that coyotes, opossums, and alligators didn’t scavenge more carrion when not competing with vultures. In other words, when vultures vanish, a lot of rotting roadkill goes uneaten.

Info collected from Mental Floss and various other sources.

- Bears, cougars, wolves, and humans are the main predators of coyotes.

- A group of coyotes is called a pack.

- Coyotes are digitigrades, which means they walk on their toes.

- Coyotes are omnivores that eat rabbits, rodents, frogs, deer, antelopes, lizards, birds, plants, and carcasses.

- They hunt at night.

- Coyotes have 42 teeth.

- They can run up to 40 MPH when chasing prey.

- Coyotes are frequent communicators that growl, bark, wail, huff, yelp, squeal, and howl.

- Coyotes are territorial and mark their area with urine.

- Coyotes are monogamous animals – meaning they mate for life.

- They mate in February and gestation takes about 2 months.

- Coyotes have 5 to 7 pups. Both male and female coyotes care for the pups in their den.

- Pups don’t open their eyes until 11 or 12 days after birth.

- Pups will hunt alone by six months.

- Coyotes are excellent swimmers.

- Coyotes know to reproduce more when their pack is SMALL.

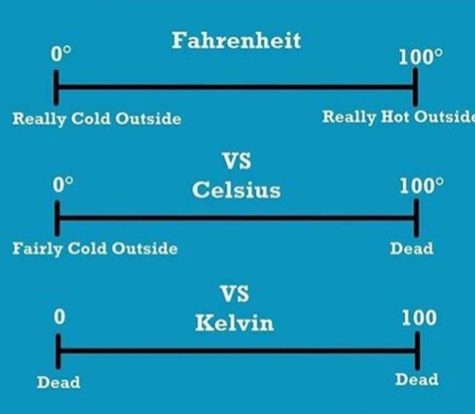

For those of us with inquiring minds, here is a vert simple infographic detailing the basic differences between the three systems of measuring the temperature.

- 0° Fahrenheit = Really Cold Outside

100° Fahrenheit = Really Hot Outside - 0° Celsius = Fairly Cold Outside

100° Fahrenheit = You’re Dead - 0° Kelvin = You’re Dead

100° Kelvin = You’re Dead

So there you have it! A nice little tidbit of information that is probably useful for absolutely nothing at all!

This cool infographic gives an image and description of all the different kinds of ladybugs (ladybirds) there are. I had no idea that there were so many! I thought they were just red with black polka dots. So interesting. If you love ladybugs, here’s a link to a post at Way Cool Pictures with some of my favorite pictures of them: Ladybug Adventures. And I also found some interesting lore about them which I posted here: Ladybird Ladybird Fly Away Home.