Bats

The truth about the bats people love to hate is even more fascinating than the myths…

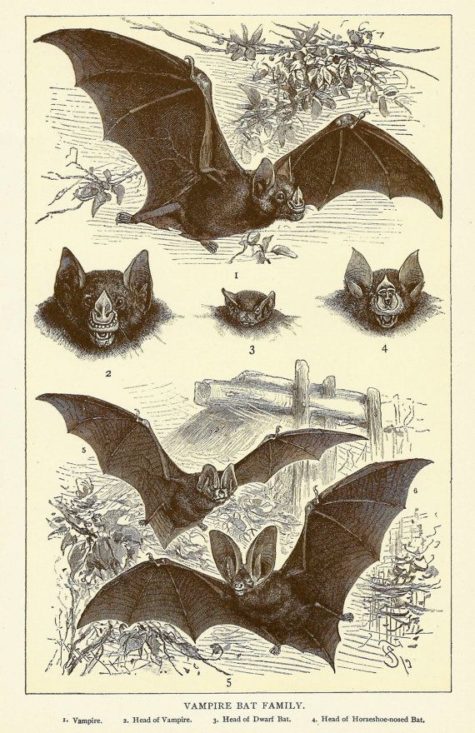

Who has not heard of vampire bats? Ask anyone what they know about bats, and tales about vampires are sure to top the list. What few people do know is that of the nearly 1,000 bat species known, only one–the common vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus–really feeds on the blood of other mammals.

Because of their need to bite in order to live, vampires have become the “black sheep” of the bat world, a reputation that unfortunately affects our attitudes toward other bats. In reality, the vampire bat is one of the most fascinating–even altruistic–animals on earth. Moreover, recent discoveries about its biology also show that it may prove to be of great importance to our own health and well-being.

Vampires feed exclusively on the blood of other vertebrates, which represents the most extreme example of food specialization in bats. There are three kinds of vampires, all of which live in Latin America. There aren’t any in the United States, except in zoos, or in Europe where the infamous Dracula legends were born. The other two species, the hairy-legged vampire (Diphylla ecaudata), and the white-winged vampire (Diaemus youngii), are rare and so poorly studied that almost nothing is known about them other than that they feed on birds.

Exactly when the blood-feeding bats were named “vampires,” and thus linked to ancient legends, is not known. Europeans were unaware of the existence of these animals until after explorers who voyaged with Columbus returned from Trinidad with the first written accounts of bats that fed on blood. Little more was heard about these unusual creatures for another 50 years, until 1565 when Cortes’ followers returned to Spain with reports of bats that bit people during the night.

In 1835, Charles Darwin became the first scientist to see a vampire bat, but it took another 70 years before taxonomic descriptions of all three vampire species were complete.

Fossil records show that, in a warmer geologic era, vampires lived as far north as California and Virginia. Today, Desmodus is found only in Latin America, from northern Mexico to northern Argentina. Vampires are adaptable and tolerate a wide variety of habitats from deserts to rain forests. They live singly or in groups of up to 2,000, but small groups of 20-100 individuals are typical. They often share roosts with other bat species, living in caves, tree hollows, abandoned mines or wells.

Vampires are commonly found near herds of cattle and horses, but this was not always the case. In Pre-Columbian times, vampires are believed to have existed in small numbers. This is true today only in undisturbed rain forests.

The arrival of European colonists 400 years ago, and specifically the livestock they brought with them, provided vampires with a new and almost limitless food supply, allowing vampire populations to grow unchecked. The unprecedented deforestation occurring in Latin America–much of it to raise yet more cattle–has allowed this trend to continue to the point where vampires have become serious agricultural pests in some areas.

Large numbers of vampires can stress livestock and sometimes transmit disease. Over the last 30 years, large-scale vampire control programs have been initiated in Latin America. Unfortunately, the result has been loss of countless thousands of highly beneficial insect-, fruit-, and nectar-eating bats that are killed annually by farmers who mistakenly assume all bats are vampires.

Despite what Hollywood movies would sometimes have us believe, the common vampire is a small bat that weighs less than two ounces and is only about four inches long. It is grayish brown in color, and as bats go, is rather unspectacular in appearance. With its flat face, it looks more like an English bulldog or pig than it does a ghoulish monster. But while vampires may appear unspectacular, closer examination reveals there is absolutely nothing ordinary about these animals.

Bats that feed on blood face many problems as a result of their specialized diets. Consequently, every aspect of their biology is affected, and vampires owe their success to the unique adaptations they have evolved to cope with their feeding habits. Truly, they are a scientific marvel.

Feeding exclusively on the blood of vertebrates, the common vampire bat represents the most extreme example of food specialization in bats.

Vampires are among the most agile of bats and are well-adapted for moving on the ground, a characteristic often needed to approach prey without detection. Using their oversized thumbs as an additional pair of feet, vampires can walk, run, hop and jump, literally leaping into flight.

Vampires feed on a wide variety of animals, extreme examples of which include sea lions and pelicans that inhabit desert regions off the coast of northern Chile. Near human settlements, however, they feed on a variety of domestic animals, including chickens, but cows, horses, and pigs appear to be their preferred prey. These animals are ideal victims; they are inactive and more or less stationary at night and possess few anti-vampire defenses.

Exactly how vampires locate and select individual prey is unknown, but it is likely that several factors are involved. First, vampires have exceptional eyesight. Extremely sensitive hearing allows them to home in on the sounds of potential prey breathing or rustling in vegetation. Olfactory cues may also help. In addition, heat-sensitive pits in their rudimentary noseleaves may enable vampires to detect prey through radiating body heat, they also enable a vampire to select areas of the body of its prey where the blood is closest to the surface.

Vampires prefer to hunt only under the darkest of conditions. As a rule, they will not fly when the moon is visible, presumably reducing detection by potential prey. Vampires have good memories, and individuals can remember the approximate location of herds on which they regularly feed. They also frequent many roosts, allowing them to follow a particular herd over a large geographic range.

Researchers have found that vampires visit some prey animals repeatedly and virtually ignore others. Why this occurs is not known, though the relative position of an animal in a herd, for example at the edge rather than in the middle, appears to be important.

Vampires either land on the ground near their intended victims or directly on the back. If the vampire approaches from the ground, it must take care not to arouse its potential host, which can weigh 10,000 times more than it does. Feeding on large prey is dangerous and is believed to account for the high mortality rate (54%) of young bats that have just begun to feed on their own. With this in mind, it is not surprising to find that vampires are among the most agile of all bat species.

Unlike most other bats, vampires spend considerable time on the ground and therefore must be able to maneuver with ease. They can run, hop, and jump with great speed. They also can stand upright and spring into the air from the ground even before spreading their wings. Vampires have exceptionally strong hind legs and long sturdy, padded thumbs that are even longer than their feet. When their wings are folded, they use their thumbs like front feet, making it possible for vampires to move like four-footed animals rather than the two-footed animals they really are.

Using their heat-sensitive nose pits, vampires select areas on the body of their prey that are well supplied with a rich bed of blood-carrying capillaries directly under the skin’s surface. Cows and horses are therefore often bitten on the back or neck.

Contrary to myth, vampires do not have an anesthetic in their saliva. Before biting, they soften the bite area by repeatedly licking a patch of skin. Their bite is swift and clean, such that sleeping prey are usually unaware of their nocturnal visitor. Contrary to what most people expect, vampires have fewer teeth than any other bats. Because they do not need to chew their food, their cheek teeth are tiny and few. Vampires use their large razor-sharp incisors to create the small crater-shaped wounds that typify their bites.

Vampires do not suck blood, instead lapping it up with a quick and continuous, in and out motion of the tongue. Blood flows up the underside of the tongue along special grooves, while saliva containing a potent anticoagulant substance flows down another groove on the upper surface.

Periodically, the bat swirls its tongue in a wound to ensure that an adequate supply of this compound (a complicated protein) is mixed with the blood. Without the anticoagulant, clotting agents in the prey’s blood would promote clot formation within a few minutes. If this were the case, each vampire’s feeding bout would last only a short time, necessitating frequent bites and increasing the risk of arousing its prey.

During feeding, specialized hairs in the bat’s facial region maintain continual contact with the prey animal and help ensure a safe feeding. Since a vampire sometimes feeds directly above the hooves on the legs of its victims, the special facial hairs, which function much like a cat’s whiskers, keep the bat alert to any movement and potential danger.

A vampire usually can remain at a wound for up to 30 minutes, drinking its fill. When finished, the first bat is often replaced by others. It is not unusual for a vampire to consume its weight in blood during a single feeding, made possible by its expandable tube-like stomach. Vampires that have recently fed have greatly distended stomachs and occasionally drink so much that they are unable to fly.

Because blood is about 80% water, vampires have a highly specialized mechanism to cope with the formidable weight they accrue each time they feed. Urination to remove excess water from ingested blood begins as soon as they start to feed, their highly efficient kidneys enabling them to concentrate adequate protein from their meal.

Vampires are very social animals. The primary grouping consists of females roosting together in small groups, their roost guarded by a lone adult male. Young males set out on their own. A typical group consists of about 20 individuals and their respective single young. Because female young often remain with their mothers after maturity, many of the bats in the roost are related.

There is much evidence to suggest that individual bats recognize one another and that groups are remarkably stable over time. Some females have been observed roosting together in the wild for at least 12 years.

Babies remain with their mothers for an exceptionally long time. Although capable of flight at eight to 10 weeks, they continue to suckle milk until they are nine to 10 months old. In the roost, contact between group members is more or less constant. When not clinging together in a tight cluster, they spend a good portion of the day grooming each other. Grooming helps maintain cleanliness while reinforcing a strong social bond.

Life is not easy for vampires. Some studies show that as many as 30% of bats in a typical group will not find food on any given night. Vampires cannot survive more than two days without a meal, but their complex social system allows them to survive, at least for short periods, without finding food.

Vampire bats will actually feed another individual regurgitated blood upon being solicited. Although this behavior is common between mother and young, it also occurs between adults. A bat that has not fed will solicit food by licking its roostmate’s body, wings, and face. If the roostmate is receptive, it responds by regurgitating blood.

Only bats that are close relatives, or who have a long-term association, will feed each other. While at first it might seem that such behavior is maladaptive (Why go to the great risk of feeding, only to give your food away to another individual?), the system has evolved because it is reciprocal. A bat that gives food today may very well need to solicit it tomorrow.

Reciprocal altruism, as it occurs in vampires, is very rare, almost non-existent, among mammals. Such behavior is known in only a few species, including wild dogs, hyenas, chimpanzees, and people. Studies of the social behavior of vampire bats have done much to help us learn about the behavior of mammals in general.

The vampire’s habit of feeding on blood, which at first appears repulsive, may actually help us solve important human problems. Heart attacks and strokes are leading causes of death in humans. Recent discoveries about the anticlotting properties of vampire bat saliva hold promise for the development of new drugs to treat these disorders.

Studies reveal that the proteins vampires use to prevent blood clotting are 20 times more powerful than any other known anticlotting substances. In addition, these proteins are more specific in their action and appear to cause fewer negative side effects (e.g. hemorrhaging) than the anticlotting agents we currently produce.

While vampires are truly fascinating animals, they can create legitimate problems when they exist in large numbers near people and domestic animals. Blood loss from occasional vampire bites rarely harms a large animal, but repeated bites, especially to a young cow or horse, can weaken the animal making it more susceptible to illness. Wounds can also be a source of infection. Screw-worm flies sometimes lay their eggs in bite wounds, which can lead to serious infection or even death.

Like all mammals, vampires can contract rabies. Although sick individuals normally die from rabies, they are capable of inflicting their prey with the disease before they do. Rabies is almost always transmitted from one animal to another via a bite.

Throughout Latin America, vampire bats are believed to cause numerous outbreaks of bovine rabies each year, resulting in high economic losses for ranchers. Some studies estimate the loss at $50 million a year.

When vampires cannot find their food of choice, they sometimes will bite humans. This often occurs when their food source suddenly disappears, such as when a cattle herd is removed or transferred to a distant pasture. The only people likely to be bitten are those sleeping outside or in buildings with screened windows.

Unlike classic myths, when vampires do bite humans, it is usually on the big toe, not the neck. When people are bitten, the local community often becomes hysterical and bat patrols are sent out to destroy any bats they can find. If the incident receives publicity, the killing often extends over a much larger area.

Most Latin American countries have large numbers of bat species. About half of these bats feed on fruit and nectar, and their seed dispersal and pollination services are essential to tropical forests. Because there seldom is an effort to distinguish between vampires and other bats, it is frequently the beneficial ones–not vampires–that die in generalized bat eradication programs.

Migratory bats from the United States, such as Mexican free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) and endangered long-nosed bats (Leptonycteris curasoae and L. nivalis) are often the victims of such actions. Because bats such as the free-tail form huge colonies, they are more conspicuous and are therefore more likely to be targeted. Moreover, entire cave ecosystems can be eliminated in the process.

One campaign in Brazil destroyed more than 8,000 caves with poison or dynamite. On a smaller scale, farmers, having observed that bats like to eat ripe bananas, set out fruit laced with poison. Upon finding dozens of dead (fruit) bats the next morning, they think they have solved their vampire problems, unaware that blood-feeding vampires have no interest in bananas.

It is only through education and carefully planned vampire control campaigns that problems can be solved, and people can come to appreciate the values of all bats. Several techniques have been developed to control vampires without causing harm to other species. Cows can be injected with small amounts of drugs harmless to the cow, but fatal to the vampires that ingest them. However, the treatment is expensive and not affordable on a large scale in developing countries.

Applying a vampiricide is another method that is both widely available and affordable. A vaseline paste, containing an anticoagulant chemical like Warfarin (a rodent poison), is applied to the backs of live vampires caught in nets. Because vampires engage in mutual grooming in their roost, they spread the vampiricide around the colony. One pasted bat can kill up to 40 others. This technique necessitates not only the capture of bats, but also the correct identification of vampires, before it can be effective.

A more targeted method is to paste the area around a fresh bite since vampires frequently return to the same site for another meal. As they feed, they ingest the paste.

It is truly unfortunate that such fascinating bats must become victims of control programs; their misfortune is a result of the way humankind has altered their habitat. Living in large numbers and feeding on domestic prey was certainly not nature’s design. Where habitat remains undisturbed by human activity, vampires still exist in small, harmless numbers, feeding on traditional prey such as tapirs.

When vampires do cause problems, all bats suffer because of our lack of understanding. There is also some evidence to suggest that growing populations of vampires may displace beneficial species from their traditional roosts.

Throughout Latin America, many problems face bats. It will be extremely difficult to plan for the conservation needs of bats in general–and for the rain forests they support–until the problem of vampires can be adequately addressed. Education is a vital component in this process, and Bat Conservation International is currently working with several Latin American countries to provide educational materials and vampire control assistance.

Mythical Vampires:

Vampire myths existed long before Europeans or the rest of the Old World ever knew of the existence of bats that fed on blood. The word “vampire” came from the Slavic vampir, meaning “blood-drunkenness,” but the mythic creatures have been called by many names. Legends of the undead abound with many variations throughout most of the world. Some of the earliest came from Babylonia: The edimmu was a troubled soul who wandered the earth in search of human victims whose veins it sucked. Many cultures had similar legends–the Greeks, Arabs, the gypsy cult in India, even the ancient Chinese.

In Europe, vampires inspired great fear and, sometimes, mass hysteria. In an attempt to explain the cause of epidemics, which often decimated entire villages, vampires frequently were blamed. Some of the strongest beliefs came from peasant tales in what is now Hungary and Romania in Eastern Europe, and the legends with which we are familiar today came largely from these. With them originated the belief that the vampire entity could leave its body at will and travel about as an animal or even as flame or smoke. Interestingly enough, bats don’t appear traditionally to have been one of those transformations.

As creatures of the night, bats had long been associated with witchcraft and demons in European traditions, both in fable and art. But most accounts agree that it wasn’t until Bram Stoker wrote his classic novel, Dracula, in 1897 that bats were linked with vampires for the first time. The seeds were planted for much of the intense fear people today have toward all bats and have been exploited ever since. Who can forget the scene from the 1931 film, Dracula, in which the elegant count, immortalized by Hungarian actor, Bela Lugosi, stands before an open balcony door, spreads his dark cape and silently takes flight, transformed into a small bat flying against the full moon?

Today, anyone who has stood in line at a supermarket checkout counter has seen lurid headlines from the tabloids, allegedly true accounts of people, who bitten by a bat, later turn into a vampire, and, of course, never age. In other stories of supposed “mass attacks,” vampire bats are almost always accused, even though most of the “reports” come from Europe and the United States, where no vampires exist outside of zoos. Worse yet, photos that accompany the stories are often of harmless fruit bats and even an insectivorous species or two. Some “eyewitness accounts” even assert that the bats are gigantic, with wings five feet or more across, and fans at least two inches long.

After centuries of tradition of the dreadful doings of human vampires, it is no wonder that a small bat who unfortunately shares but one characteristic with their mythic human counterpart–the need to consume blood in order to live–also came to be feared and despised. And it further should be no wonder that this fear has carried over to include all bats.

Source: BATS Magazine

Are the stories about bat bombs true? Actually, yes!

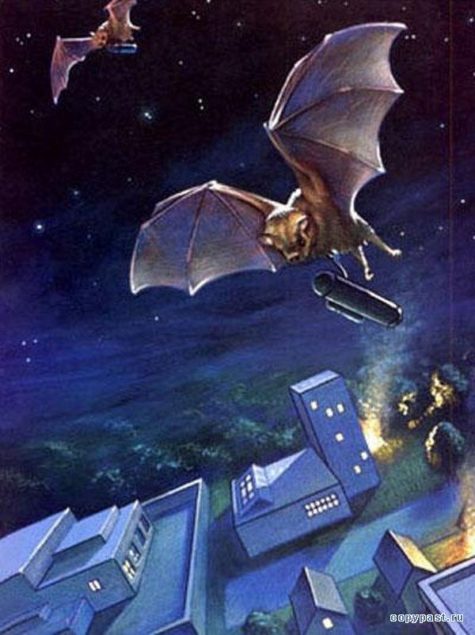

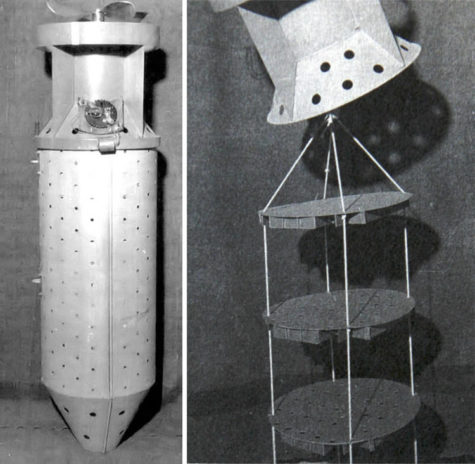

Bat bombs were an experimental World War II weapon developed by the United States. The bomb consisted of a bomb-shaped casing with over a thousand compartments, each containing a hibernating Mexican free-tailed bat with a small, timed incendiary bomb attached.

Dropped from a bomber at dawn, the casings would deploy a parachute in mid-flight and open to release the bats, which would then roost in eaves and attics in a 20–40 mile radius. The incendiaries would start fires in inaccessible places in the largely wood and paper constructions of the Japanese cities that were the weapon’s intended target.

I find it horrifying that anyone would be so callously uncaring about the brutal slaughter of these gentle creatures of the night. But it’s the government… and there was a war on… and death and destruction was the end game.

Here’s the story:

On December 7, 1941, a Pennsylvania dentist named Lytle S. Adams was on vacation in the southwest at the famed Carlsbad Caverns, home to excellent spelunking and about a million bats. Adams had been particularly impressed with the bats during his time in New Mexico. So when he turned on the radio that infamous day and heard the news that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor, he began plotting a very unusual form of revenge on our World War II enemies.

Less than a month later, on January 12, 1942, he sent the White House his plan: We could demolish Japanese cities by strapping tiny incendiary bombs to bats, which they would carry into the all the nooks and crannies of the cities on the island. “Think of thousands of fires breaking out simultaneously over a circle of forty miles in diameter for every bomb dropped,” he later recalled. Japan could have been devastated, yet with small loss of life.”

Now, as luck would have it, Adams happened to know Eleanor Roosevelt. He’d flown her in his plane to see a previous scheme he’d cooked up: an airmail system where the plane doesn’t have to land to pick up cargo. So, when he finished his preliminary investigations, he appears to have managed to get a high-level audience, despite the rather eccentric nature of his idea.

His proposal was taken up by the National Research Defense Committee, which was in charge of coordinating and investigating research into war-applicable ideas.

His proposal was taken up by the National Research Defense Committee, which was in charge of coordinating and investigating research into war-applicable ideas.

They forwarded the proposal to one Donald Griffin, who had conducted groundbreaking work on bats’ echolocation strategies, as related by Patrick Drumm and Christopher Ovre in this month’s American Psychological Association Journal. Griffin, who later became a renowned psychologist who argued that non-human animals also possess consciousness, was quite enthusiastic about the idea.

“This proposal seems bizarre and visionary at first glance,” he wrote in April 1942, “but extensive experience with experimental biology convinces the writer that if executed competently it would have every chance of success.”

The President’s men followed Griffin’s lead. “This man is not a nut. It sounds like a perfectly wild idea but is worth looking into,” a Presidential memorandum concluded. And so, just like that, a dentist’s crazy idea about bats had become a U.S. government research project.

After the team settled on using the Mexican free-tailed bat, Adams took a few to Washington for a demonstration of them carrying a dummy bomb. His superiors were sufficiently impressed that the U.S. Air Force gave authority for investigations to begin in earnest. It was March of 1943. The subject of the letter was, “Test of Method to Scatter Incendiaries.” The purpose of the test was listed as, “Determine the feasibility of using bats to carry small incendiary bombs into enemy targets.” The scheme became known as Project X-Ray.

After being transferred to the Army, thousands of bats were captured with nets at caverns around the southwest. Tiny bombs were designed for them. Appreciate, for a moment, the incendiary bomb that they came up with:

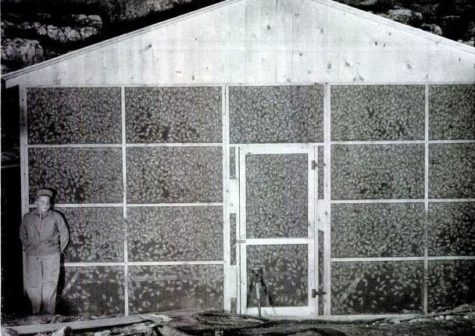

But this was a complex system that was being engineered. The researchers needed to figure out how to transport and deploy the little guys. So they did. First, the bats had to be kept in a hibernating mode while they were shipped. To accomplish this, they were stuck in ice cube trays and cooled. Second, they had to figure out how to release them in midair. A cardboard container was supposed to automatically open and release the bats.

This was a real effort that cost science and engineering effort. Unfortunately, real tests did not go as planned. There were all kinds of things that needed to be fine-tuned. For example, at one point, a few of the loaded incendiary bats were accidentally released, whereupon a hangar and general’s car were burned (as you can see in the photo below).

Eventually the Marine Corps took over the program and conducted tests beginning in December 1943. After 30 demonstrations and $2 million spent, the project was canceled.

The infamous “Invasion by Bats” project was afterwards referred to by Stanley P. Lovell, director of research and development for Office of Strategic Services, whom General Donovan ordered to review the idea, as “Die Fledermaus Farce“. Lovell also mentioned that bats during testing were dropping to the ground like stones.

Sources: