Death

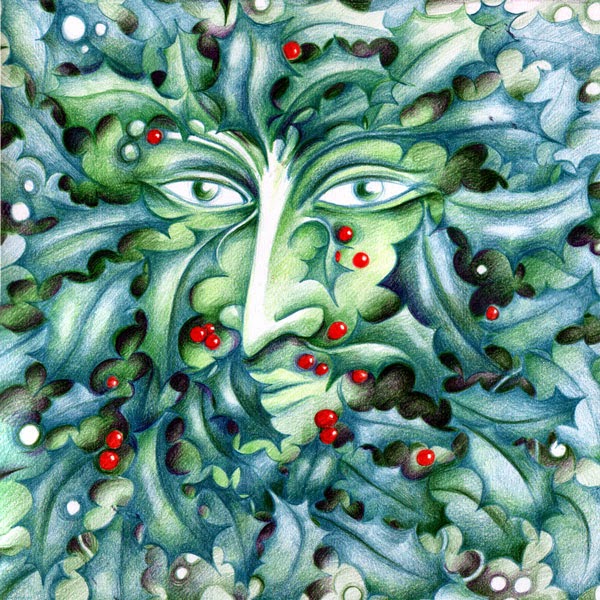

The Juniper Tree

Long ago, at least two thousand years, there was a rich man who had a beautiful and pious wife, and they loved each other dearly. However, they had no children, though they wished very much to have some, and the woman prayed for them day and night, but they didn’t get any, and they didn’t get any.

In front of their house there was a courtyard where there stood a juniper tree. One day in winter the woman was standing beneath it, peeling herself an apple, and while she was thus peeling the apple, she cut her finger, and the blood fell into the snow.

“Oh,” said the woman. She sighed heavily, looked at the blood before her, and was most unhappy. “If only I had a child as red as blood and as white as snow.” And as she said that, she became quite contented, and felt sure that it was going to happen.

Then she went into the house, and a month went by, and the snow was gone. And two months, and everything was green. And three months, and all the flowers came out of the earth. And four months, and all the trees in the woods grew thicker, and the green branches were all entwined in one another, and the birds sang until the woods resounded and the blossoms fell from the trees. Then the fifth month passed, and she stood beneath the juniper tree, which smelled so sweet that her heart jumped for joy, and she fell on her knees and was beside herself. And when the sixth month was over, the fruit was thick and large, and then she was quite still. And after the seventh month she picked the juniper berries and ate them greedily.

Then she grew sick and sorrowful. Then the eighth month passed, and she called her husband to her, and cried, and said, “If I die, then bury me beneath the juniper tree.” Then she was quite comforted and happy until the next month was over, and then she had a child as white as snow and as red as blood, and when she saw it, she was so happy that she died.

Her husband buried her beneath the juniper tree, and he began to cry bitterly. After some time he was more at ease, and although he still cried, he could bear it. And some time later he took another wife.

He had a daughter by the second wife, but the first wife’s child was a little son, and he was as red as blood and as white as snow. When the woman looked at her daughter, she loved her very much, but then she looked at the little boy, and it pierced her heart, for she thought that he would always stand in her way, and she was always thinking how she could get the entire inheritance for her daughter.

And the Evil One filled her mind with this until she grew very angry with the little boy, and she pushed him from one corner to the other and slapped him here and cuffed him there, until the poor child was always afraid, for when he came home from school there was nowhere he could find any peace.

One day the woman had gone upstairs to her room, when her little daughter came up too, and said, “Mother, give me an apple.”

“Yes, my child,” said the woman, and gave her a beautiful apple out of the chest. The chest had a large heavy lid with a large sharp iron lock.

“Mother,” said the little daughter, “is brother not to have one too?”

This made the woman angry, but she said, “Yes, when he comes home from school.”

When from the window she saw him coming, it was as though the Evil One came over her, and she grabbed the apple and took it away from her daughter, saying, “You shall not have one before your brother.”

She threw the apple into the chest, and shut it. Then the little boy came in the door, and the Evil One made her say to him kindly, “My son, do you want an apple?” And she looked at him fiercely.

“Mother,” said the little boy, “how angry you look. Yes, give me an apple.”

Then it seemed to her as if she had to persuade him. “Come with me,” she said, opening the lid of the chest. “Take out an apple for yourself.” And while the little boy was leaning over, the Evil One prompted her, and crash! she slammed down the lid, and his head flew off, falling among the red apples.

Then fear overcame her, and she thought, “Maybe I can get out of this.” So she went upstairs to her room to her chest of drawers, and took a white scarf out of the top drawer, and set the head on the neck again, tying the scarf around it so that nothing could be seen. Then she set him on a chair in front of the door and put the apple in his hand.

After this Marlene came into the kitchen to her mother, who was standing by the fire with a pot of hot water before her which she was stirring around and around.

“Mother,” said Marlene, “brother is sitting at the door, and he looks totally white and has an apple in his hand. I asked him to give me the apple, but he did not answer me, and I was very frightened.”

“Go back to him,” said her mother, “and if he will not answer you, then box his ears.”

So Marlene went to him and said, “Brother, give me the apple.” But he was silent, so she gave him one on the ear, and his head fell off. Marlene was terrified, and began crying and screaming, and ran to her mother, and said, “Oh, mother, I have knocked my brother’s head off,” and she cried and cried and could not be comforted.

“Marlene,” said the mother, “what have you done? Be quiet and don’t let anyone know about it. It cannot be helped now. We will cook him into stew.”

Then the mother took the little boy and chopped him in pieces, put him into the pot, and cooked him into stew. But Marlene stood by crying and crying, and all her tears fell into the pot, and they did not need any salt.

Then the father came home, and sat down at the table and said, “Where is my son?” And the mother served up a large, large dish of stew, and Marlene cried and could not stop.

Then the father said again, “Where is my son?”

“Oh,” said the mother, “he has gone across the country to his mother’s great uncle. He will stay there awhile.”

“What is he doing there? He did not even say good-bye to me.”

“Oh, he wanted to go, and asked me if he could stay six weeks. He will be well taken care of there.”

“Oh,” said the man, “I am unhappy. It isn’t right. He should have said good-bye to me.” With that he began to eat, saying, “Marlene, why are you crying? Your brother will certainly come back.”

Then he said, “Wife, this food is delicious. Give me some more.” And the more he ate the more he wanted, and he said, “Give me some more. You two shall have none of it. It seems to me as if it were all mine.” And he ate and ate, throwing all the bones under the table, until he had finished it all.

Marlene went to her chest of drawers, took her best silk scarf from the bottom drawer, and gathered all the bones from beneath the table and tied them up in her silk scarf, then carried them outside the door, crying tears of blood.

She laid them down beneath the juniper tree on the green grass, and after she had put them there, she suddenly felt better and did not cry anymore.

Then the juniper tree began to move. The branches moved apart, then moved together again, just as if someone were rejoicing and clapping his hands. At the same time a mist seemed to rise from the tree, and in the center of this mist it burned like a fire, and a beautiful bird flew out of the fire singing magnificently, and it flew high into the air, and when it was gone, the juniper tree was just as it had been before, and the cloth with the bones was no longer there. Marlene, however, was as happy and contented as if her brother were still alive. And she went merrily into the house, sat down at the table, and ate.

Then the bird flew away and lit on a goldsmith’s house, and began to sing:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

The goldsmith was sitting in his workshop making a golden chain, when he heard the bird sitting on his roof and singing. The song seemed very beautiful to him. He stood up, but as he crossed the threshold he lost one of his slippers. However, he went right up the middle of the street with only one slipper and one sock on. He had his leather apron on, and in one hand he had a golden chain and in the other his tongs. The sun was shining brightly on the street.

He walked onward, then stood still and said to the bird, “Bird,” he said, “how beautifully you can sing. Sing that piece again for me.”

“No,” said the bird, “I do not sing twice for nothing. Give me the golden chain, and then I will sing it again for you.”

The goldsmith said, “Here is the golden chain for you. Now sing that song again for me.” Then the bird came and took the golden chain in his right claw, and went and sat in front of the goldsmith, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Then the bird flew away to a shoemaker, and lit on his roof and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Hearing this, the shoemaker ran out of doors in his shirtsleeves, and looked up at his roof, and had to hold his hand in front of his eyes to keep the sun from blinding him. “Bird,” said he, “how beautifully you can sing.”

Then he called in at his door, “Wife, come outside. There is a bird here. Look at this bird. He certainly can sing.” Then he called his daughter and her children, and the journeyman, and the apprentice, and the maid, and they all came out into the street and looked at the bird and saw how beautiful he was, and what fine red and green feathers he had, and how his neck was like pure gold, and how his eyes shone like stars in his head.

“Bird,” said the shoemaker, “now sing that song again for me.”

“No,” said the bird, “I do not sing twice for nothing. You must give me something.”

“Wife,” said the man, “go into the shop. There is a pair of red shoes on the top shelf. Bring them down.” Then the wife went and brought the shoes.

“There, bird,” said the man, “now sing that piece again for me.” Then the bird came and took the shoes in his left claw, and flew back to the roof, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

When he had finished his song he flew away. In his right claw he had the chain and in his left one the shoes. He flew far away to a mill, and the mill went clickety-clack, clickety-clack, clickety-clack. In the mill sat twenty miller’s apprentices cutting a stone, and chiseling chip-chop, chip-chop, chip-chop. And the mill went clickety-clack, clickety-clack, clickety-clack.

Then the bird went and sat on a linden tree which stood in front of the mill, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

Then one of them stopped working.

My father, he ate me,

Then two more stopped working and listened,

My sister Marlene,

Then four more stopped,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Now only eight only were chiseling,

Laid them beneath

Now only five,

the juniper tree,

Now only one,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Then the last one stopped also, and heard the last words. “Bird,” said he, “how beautifully you sing. Let me hear that too. Sing it once more for me.”

“No,” said the bird, “I do not sing twice for nothing. Give me the millstone, and then I will sing it again.”

“Yes,” he said, “if it belonged only to me, you should have it.”

“Yes,” said the others, “if he sings again he can have it.”

Then the bird came down, and the twenty millers took a beam and lifted the stone up. Yo-heave-ho! Yo-heave-ho! Yo-heave-ho!

The bird stuck his neck through the hole and put the stone on as if it were a collar, then flew to the tree again, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

My father, he ate me,

My sister Marlene,

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

When he was finished singing, he spread his wings, and in his right claw he had the chain, and in his left one the shoes, and around his neck the millstone. He flew far away to his father’s house.

In the room the father, the mother, and Marlene were sitting at the table.

The father said, “I feel so contented. I am so happy.”

“Not I,” said the mother, “I feel uneasy, just as if a bad storm were coming.”

But Marlene just sat and cried and cried.

Then the bird flew up, and as it seated itself on the roof, the father said, “Oh, I feel so truly happy, and the sun is shining so beautifully outside. I feel as if I were about to see some old acquaintance again.”

“Not I,” said the woman, “I am so afraid that my teeth are chattering, and I feel like I have fire in my veins.” And she tore open her bodice even more. Marlene sat in a corner crying. She held a handkerchief before her eyes and cried until it was wet clear through.

Then the bird seated itself on the juniper tree, and sang:

My mother, she killed me,

The mother stopped her ears and shut her eyes, not wanting to see or hear, but there was a roaring in her ears like the fiercest storm, and her eyes burned and flashed like lightning.

My father, he ate me,

“Oh, mother,” said the man, “that is a beautiful bird. He is singing so splendidly, and the sun is shining so warmly, and it smells like pure cinnamon.”

My sister Marlene,

Then Marlene laid her head on her knees and cried and cried, but the man said, “I am going out. I must see the bird up close.”

“Oh, don’t go,” said the woman, “I feel as if the whole house were shaking and on fire.”

But the man went out and looked at the bird.

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

With this the bird dropped the golden chain, and it fell right around the man’s neck, so exactly around it that it fit beautifully. Then the man went in and said, “Just look what a beautiful bird that is, and what a beautiful golden chain he has given me, and how nice it looks.”

But the woman was terrified. She fell down on the floor in the room, and her cap fell off her head. Then the bird sang once more:

My mother killed me.

“I wish I were a thousand fathoms beneath the earth, so I would not have to hear that!”

My father, he ate me,

Then the woman fell down as if she were dead.

My sister Marlene,

“Oh,” said Marlene, “I too will go out and see if the bird will give me something.” Then she went out.

Gathered all my bones,

Tied them in a silken scarf,

He threw the shoes down to her.

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Tweet, tweet, what a beautiful bird am I.

Then she was contented and happy. She put on the new red shoes and danced and leaped into the house. “Oh,” she said, “I was so sad when I went out and now I am so contented. That is a splendid bird, he has given me a pair of red shoes.”

“No,” said the woman, jumping to her feet and with her hair standing up like flames of fire, “I feel as if the world were coming to an end. I too, will go out and see if it makes me feel better.”

And as she went out the door, crash! the bird threw the millstone on her head, and it crushed her to death.

The father and Marlene heard it and went out. Smoke, flames, and fire were rising from the place, and when that was over, the little brother was standing there, and he took his father and Marlene by the hand, and all three were very happy, and they went into the house, sat down at the table, and ate.

Story by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

The Knot of Isis

At the ends of the universe is a blood red cord that ties life to death, man to woman, will to destiny. Let the knot of that red sash, which cradles the hips of the goddess, bind in me the ends of life and dream. I’m an old man with more than my share of hopes and misgivings. Let my thoughts lie together in peace. At my death let the bubbles of blood on my lips taste as sweet as berries. Give me not words of consolation. Give me magic, the fire of one beyond the borders of enchantment. Give me the spell of living well.

Do I lie on the floor of my house or within the temple? Is the hand that soothes me that of wife or priestess? I rise and walk. The sky arcs ever around; the world spreads itself beneath my feet. We are bound mind to Mind, heart to Heart ~ no difference rises between the shadow of my footsteps and the will of god. I walk in harmony, heaven in one hand, earth in the other. I am the knot where two worlds meet. Red magic courses through me like the blood of Isis, magic of magic, spirit of spirit. I am proof of the power of gods. I am water and dust walking.

From Awakening Osiris

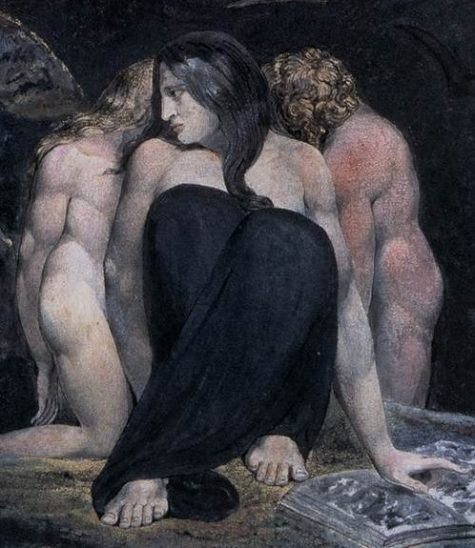

Hekate Speaks

I am the Guardian of the Mysteries

The Guardian of the Serpent Power

Whom you have called upon time and time again

Hekate the beauteous

Hekate of the crossroads

Of Heaven of Earth of Sea

Of Life of Death of Rebirth

I am the Saffron Clad Terrible Queen

Feared, Hated, Loved

I will lead you into the shadows and Light the darkest night

Tonight my chosen

I reveal that which is hidden and forbidden

My torches will illuminate the way

To the inner most reaches of the self

where even you may fear to look

Yet there is power in the dark!

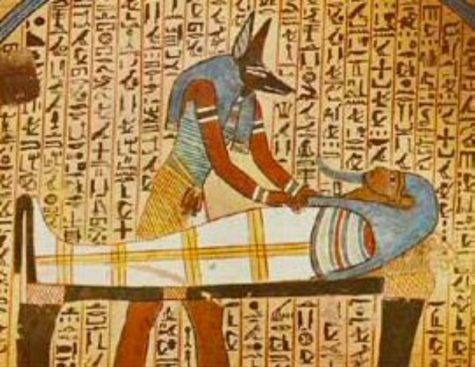

Words of Power For The Dead

In the Theban Recension of the Book of the Dead is found a Chapter which was composed for the purpose of bestowing upon the deceased some of the magical power of the goddess Isis. The Chapter was intended to be recited over an amulet called thet, made of carnelian, which had to be steeped in water of ankhami flowers, and set in a sycamore plinth, and if this were laid on the neck of a dead person it would place him under the protection of the words of power of Isis, and he would be able to go wheresoever he pleased in the Underworld.

The words of the Chapter were:

“Let the blood of Isis, and the magical powers (or spirits) of Isis, and the words of power of Isis, be mighty to protect and keep safely this great god (i.e., the deceased), and to guard him from him that would do unto him anything which he abominateth.”

Isis and Words of Power:

From a number of passages in the texts of various periods we learn that Isis possessed great skill in the working of magic, and several examples of the manner in which she employed it are well known.

Thus when she wished to make Ra reveal to her his greatest and most secret name, she made a venomous reptile out of dust mixed with the spittle of the god, and by uttering over it certain words of power she made it to bite Ra as he passed. When she had succeeded in obtaining from the god his most hidden name, which he only revealed because he was on the point of death, she uttered words which had the effect of driving the poison out of his limbs, and Ra recovered.

Now Isis not only used the words of power, but she also had knowledge of the way in which to pronounce them so that the beings or things to which they were addressed would be compelled to listen to them and, having listened, would be obliged to fulfill her bequests. The Egyptians believed that if the best effect was to be produced by words of power they must be uttered in a certain tone of voice, and at a certain rate, and at a certain time of the day or night, with appropriate gestures or ceremonies.

In the Hymn to Osiris it is said that Isis was well skilled in the use of words of power, and it was by means of these that she restored her husband to life, and obtained from him an heir. It is not known what the words were which she uttered on this occasion, but she appears to have obtained them from Thoth, the “lord of divine words,” and it was to him that she appealed for help to restore Horus to life after he had been stung to death by a scorpion.

From Gods of the Egyptians (1904)

Litany For The Dead

From The Papyrus of Ani, we have this Egyptian litany for the dead:

Homage to you, stars in Heliopolis, men and women in Kher-aha, god of existence, more glorious than the hidden gods in Heliopolis.

Homage to you, o moon-god Iwen in Iwen-des, great god, Harmachis travelling with long strides over heaven, he is Harmachis.

Homage to you, who is the soul of eternity, the soul in Busiris, Wen-nefer son of Nut, he is lord of the necropolis of Heliopolis.

Homage to you, in your kingdom of Busiris, the double crown remains on your head; you alone perform his protection; you rest in Busiris.

Homage to you, lord of the sycamore, placing the boat of Seker on its sledge, warding off demons who do evil, placing the Eye of Ra to rest on its seat.

Homage to you, who is mighty in his moment, most great one in the Place where Nothing Grows, lord of eternity, maker of infinity, you are lord of Herakleopolis.

Homage to you, who rests on truth, you are the lord of Abydos; your limbs are brought together in the Holy Land; you are he who loathes falsehood.

Homage to you, in his boat, bringing Hapi from his caverns. His light shines on his body; he is in Hierakonpolis.

Homage to you, maker of the gods, king of the South and North, Osiris, true of voice, founder of the Two Lands in his benevolent era; it is he who is lord of the banks of the Nile.

May you give me a way where I may pass in peace. I am judged true; I do not knowingly speak falsehoods, and I do not act doubly.

Mioriţa

Though there are countless whimsical and ghostly tales, Mioriţa is a folklore poem, exclusive to Romania. There are over 1,500 variants of the poem and was conceived in Transylvania. The poem, which was translated into a ballad, is based on an initiation rite and is sung in the form of carols during the winter holidays. It’s cultural significance is that it has been shared among some of the most influential and important people of Romania. Having been translated into over 20 languages, the Mioritic has been the inspiration for countless writers, composers and artists. It is one of the most popular of the four traditional myths of Romanian literature. Here is the translated version:

Mioriţa

Near a low foothill

At Heaven’s doorsill,

Where the trail’s descending

To the plain and ending,

Here three shepherds keep

Their three flocks of sheep,

One, Moldavian,

One, Transylvanian

And one, Vrancean.

Now, the Vrancean

And the Transylvanian

In their thoughts, conniving,

Have laid plans, contriving

At the close of day

To ambush and slay

The Moldavian;

He, the wealthier one,

Had more flocks to keep,

Handsome, long-horned sheep,

Horses, trained and sound,

And the fiercest hounds.

One small ewe-lamb, though,

Dappled gray as tow,

While three full days passed

Bleated loud and fast;

Would not touch the grass.

”Ewe-lamb, dapple-gray,

Muzzled black and gray,

While three full days passed

You bleat loud and fast;

Don’t you like this grass?

Are you too sick to eat,

Little lamb so sweet?”

”Oh my master dear,

Drive the flock out near

That field, dark to view,

Where the grass grows new,

Where there’s shade for you.

”Master, master dear,

Call a large hound near,

A fierce one and fearless,

Strong, loyal and peerless.

The Transylvanian

And the Vrancean

When the daylight’s through

Mean to murder you.”

”Lamb, my little ewe,

If this omen’s true,

If I’m doomed to death

On this tract of heath,

Tell the Vrancean

And Transylvanian

To let my bones lie

Somewhere here close by,

By the sheepfold here

So my flocks are near,

Back of my hut’s grounds

So I’ll hear my hounds.

Tell them what I say:

There, beside me lay

One small pipe of beech

With its soft, sweet speech,

One small pipe of bone

Whit its loving tone,

One of elderwood,

Fiery-tongued and good.

Then the winds that blow

Would play on them so

All my listening sheep

Would draw near and weep

Tears, no blood so deep.

How I met my death,

Tell them not a breath;

Say I could not tarry,

I have gone to marry

A princess – my bride

Is the whole world’s pride.

At my wedding, tell

How a bright star fell,

Sun and moon came down

To hold my bridal crown,

Firs and maple trees

Were my guests; my priests

Were the mountains high;

Fiddlers, birds that fly,

All birds of the sky;

Torchlights, stars on high.

But if you see there,

Should you meet somewhere,

My old mother, little,

With her white wool girdle,

Eyes with their tears flowing,

Over the plains going,

Asking one and all,

Saying to them all,

’Who has ever known,

Who has seen my own

Shepherd fine to see,

Slim as a willow tree,

With his dear face, bright

As the milk-foam, white,

His small mustache, right

As the young wheat’s ear,

With his hair so dear,

Like plumes of the crow

Little eyes that glow

Like the ripe black sloe?’

Ewe-lamb, small and pretty,

For her sake have pity,

Let it just be said

I have gone to wed

A princess most noble

There on Heaven’s door sill.

To that mother, old,

Let it not be told

That a star fell, bright,

For my bridal night;

Firs and maple trees

Were my guests, priests

Were the mountains high;

Fiddlers, birds that fly,

All birds of the sky;

Torchlights, stars on high.”

We Remember Them

At the rising of the sun

and at its going down,

We remember them.

At the blowing of the wind

and in the chill of Winter,

We remember them.

At the opening of buds

and in the rebirth of Spring,

We remember them.

At the blueness of the skies

and in the warmth of Summer,

We remember them.

At the rustling of leaves

and the beauty of Autumn,

We remember them.

At the beginning of the year

and when it ends,

We remember them.

As long as we live,

they too will live;

for they are now a part of us,

as we remember them.

When we are weary

and in need of strength,

We remember them.

When we are lost

and sick at heart,

We remember them.

When we have joys we yearn to share,

We remember them.

When we have decisions

that are difficult to make,

We remember them

When we have achievements

that are based on theirs,

We remember them.

As long as we live,

they too shall live,

for they are a part of us,

as we remember them.

~by Rabbi Jack Riemer

Isis Heed My Call

O Isis, heed my call this night,

If it is time for my spirit to flee this shell,

then send those who will

guide me to your light!

Grant me rest O Beloved Mother,

for Your child is wracked with pain.

If my time has yet to come,

help me Great One to heal from within.

O Isis, heed my call this night!

Source: Liberated Thinking

The Legend of Pancake Marion

There’s been a lot of talk of late about Pancake Marion, and the whole “Shrove Tuesday” phenomenon. But just who is she? And why did she do the horrible things that she did? Historian Marcus Ploughmans looks back at the history of one of England’s darkest secrets.

“Pancake Marion, Pancake Marion

Now’s the time to fry them

Pancake Marion, Pancake Marion

Now’s the time to fry

Don’t you dare to drop them

On the table plop them

Tuesday’s day is pancake day

We dance our cares away”

The ever-popular children’s nursery rhyme is now only ever really associated with cooking pancakes. But there was once a time when it was sung to remind children of the dangers of going into the darkness of Marionwood, Herefordshire.

The Raven-Barrow Family Portrait

In 1854, Jonathon Raven-Barrow (a wealthy industrialist from Westminster, London) lost his entire fortune to bad investments made in overseas property. Jonathon, his wife and their daughter, Marion, were homeless and destitute. They were forced to live in makeshift accommodation in the woodlands of Hereford, surviving by eating scraps, scavenged from the dustbins of the local townsfolk.

But, unknown to the Raven-Barrows, the villagers had grown tired of the rogue family’s presence. They saw the family as vermin. The woods were once a play area for children, but had become a no-go area since the Raven-Barrows had taken over. The villagers conspired to trap the family, and, on the night of the 14th of February 1857, caught them deep within the woods.

One by one, they were boiled alive in a vat of rancid eggs and lard…ingredients that were consistently stolen. As Marion was being executed she managed to escape. The villagers assumed that her fierce wounds would finish her off. But they were wrong. She lived. Albeit deformed and unhinged. Her mind twisted by the sight of the murder of her parents.

She fed off wild animals…to begin with! When the animals ran out…she turned to the children of the village. And anyone else who was foolish enough to go into the woods. All were captured…tortured and eaten alive, covered in boiling batter. They called her Pancake Marion.

Armies of men would march into the woods, all carrying weapons…but none would return. In a five year period she claimed over 200 victims. Eventually, the woods were burned to the ground. It seemed the only way to end her reign of terror. And the name of Pancake Marion became a thing of folklore.

Source: Wikipedia

The Doom of Odin

“I find no comfort in the shade

Under the branch of the Great Ash.

I remember the mist

of our ancient past.

As I speak to you in the present,

My ancient eyes

see the terrible future.

“Do you not see what I see?

Do you not hear

death approaching?

“The mournful cry of Giallr-horn

shall shatter the peace

And shake the foundation of heaven.

“Raise up your banner

And gather your noble company

from your great hall,

Father of the Slains.

For you shall go to your destiny.

“No knowledge can save you,

And no magic will save you.

For you will end up in Fenrir’s belly,

While heaven and earth will burn

in Surt’s unholy fire.”

— Doom of Odin,

from the Book of Heroes

James Cheney: Invocation To The Dark Mother

Daniel: Prayer Before The Final Battle

blessed obyno: Queen of Ghosts

blessed obyno: Queen of Ghosts

Caerlion Arthur: The Great, Bloody and Bruised Veil of the World