Informational

About The Orissa Art Tradition

Orissa is situated at the eastern coast of India. The state of India has been the home of rich art and culture since time immemorial. Orissa was earlier called Utkal or ‘land of rich art forms’ in deference to its wealth of arts and crafts.

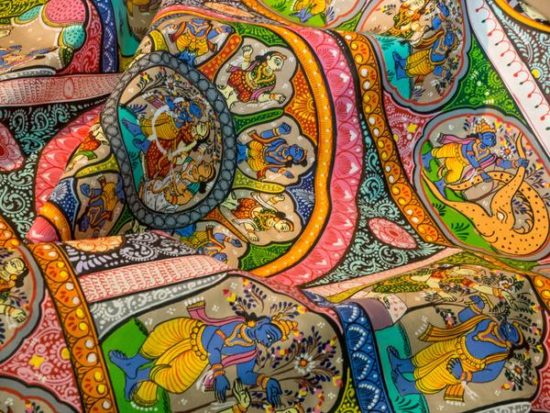

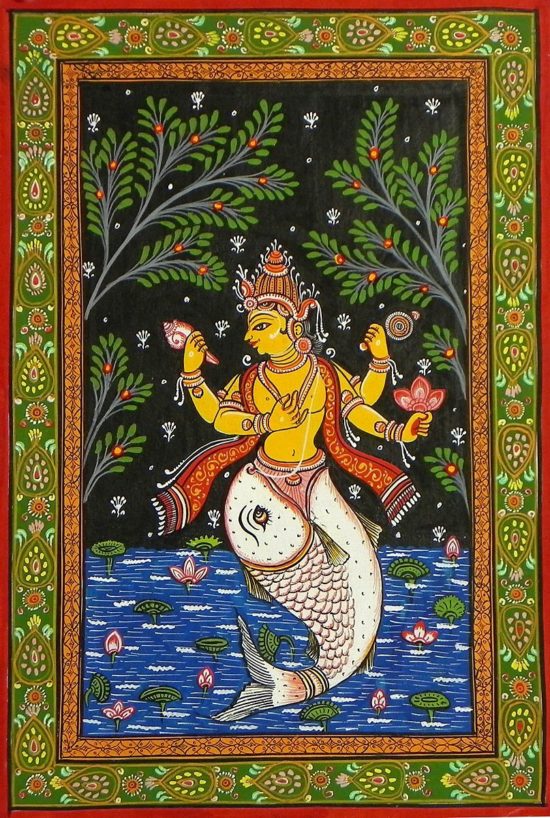

The Patta Chitra, one of the fascinating art form of Orissa has a tradition that goes back centuries. Soaked in puranic culture and classical romances, with vibrant colors, superb craftmanship, simplicity in design the patta chitra is a distinct form of art and has captured the imagination of artists and art lovers alike. The term patta chitra has its origin from the Sanskrit. Patta means vastra or cloth and chitra means paintings. So patta chitra means paintings on cloth.

The use of cloth for painting has been in vogue in India for a very long time. So also was the case with Orissa. It is said that thin cloth paintings were sent to China from Orissa during the rule of Bhaumakars and the craftmanship was highly appreciated.

The patta painting has its root in religion. It is evolved, nourished and flourished under the cult of Lord Jagannath. Therefore the Patta paintings of Orissa is considered to be as old as the construction of the temple of Lord Jagannath at Puri. i.e. 12th Century A.D.

The subject matter of Patta paintings is traditionally limited to Hindu religious themes. However, as time passed, the subject matter as become widely varied. In addition to the stories from Ramayan, Mahabharat and Vesas of Jagannath, new themes on the life and philosophy of Lord Buddha, pictures on Jainism, Jesus Christ and important historical events are also depicted in patta paintings.

In recent years some artists are putting modern concepts/themes to it. Some PACADian animators are doing animation with pattachitra style. With the advancement of time, a lot of changes have been noticed in the preparation, color, theme, approach to the subject and in, the market-ability of patta paintings.

The Traditional Method Of Painting

The preparation of pattas on canvas in its traditional way for painting is very interesting. It is ingenuously prepared. A large piece of cloth is washed neatly and spread out over the surface of a cot or on the varandah floor. The tamarind seed is powdered and some water is put on it to prepare a special gum. This gum is applied over this piece of cloth. Before this gum dries up, another piece of the cloth of same size is placed on it and a fresh coating of gum is pasted on it.

Then the patta is allowed to dry in the sun. After it is dried, a chalk like paste of soft white stone powder and tamarind seed gum is mixed in an ideal proportion and applied on both sides. After both sides dry completely, the cloth is cut into required sizes.

After cutting to sizes, the next work is to polish it to make them smooth and suitable for painting. The polishing is first made with a rough stone and then it is polished with a pebble whose surface is smooth. The polishing require long hours of work. The work of preparation of the pati for painting is traditionally done only by the woman folk of the chitrakar families.

Then over the polished cloth, which looks off white in color, the chitrakar start painting on it. The colors used are bright and primarily white, red, yellow, blue, green and black. Red is used predominantly for the back ground.

The colors are prepared out of the natural ingredients.

- White is prepared from powder of conch-shell

- Yellow from Haritala, a kind of stone

- Red from geru (Dheu)

- Hingula black from burning lamp and coconut shell

- Green from leaves

The artists follow a sequential procedure for preparation of the paintings. Single tone colors are used. First the border and the sketch is drawn on the patis either in pencil or in a light color. The artists put correct lines to make the figure more prominent. The lines are broad and steady, then the color is applied.

The visual appeal of a patta painting is in its color combination.The human figures are generally presented frontally but the face, leg are shown side-wise but the elongated eyes are drawn from the front side. Sharp nose and round chins are prominently depicted. The typical hair style, clothing, ornamentation, beards and mustaches are used for different persons, so that there will not been any confusion to recognize which figure is a king, minister sage, royal priest, common man, the God, the Goddesses and the like.

A decorative border is drawn on all sides to give it a frame like look. In this style of painting overlapping is avoided as far as possible. Also, the sense of far and near is neglected. The typical face style makes this type of painting different from other schools of art. The paintings are conspicuous for their elegance charm and aesthetic appeal. Central focus of the painting is the expression of the figures and the emotion they portray, the strong color only reinforce them.

Traditionally, three types of brushes were used. They are broad, medium and fine. These are prepared out of the hairs of the buffalo, calf and the mouse respectively. The Pattachitra style has been elaborated and applications are made on other items besides the Patis. Paintings are made on wooden and bamboo boxes, masks, and pots. Ganjapa, playing cards are also painted in this style. Palm leaf is also used as a base for patta paintings.

The Patta chitra artists are known as chitrakaaras. This family occupation is a tradition is inherited by the artists and passed along through the generations.

This unique form of art must be protected and nourished for generations to come.

Source: Wet Canvas

About Ganjapa Playing Cards

In the 16th Century in Orissa, circular cards with exquisite paintings on them – an art called Ganjapa were very popular among the people of Ganjam; they were used to play ordinary card games. Ganjapa, also called “Ganjapa” is derived from a Persian word “Gajife.“ The earliest mention of Ganjapa is in 1527 A.D. in the memoirs of Emperor Babur.

The cards are arranged in sets in packs of different numbers such as 46, 96, 120, 144 and so on. Each pack has sets of 12 cards, with each set being a different color.

Based on the number of colors in a set, the packs are called atharangi (eight colors), dasarangi (10 colors), bararangi (12 colors), chaudarangi (14 colors) and sholarangi (16 colors). A maximum of 24 colors are used. Of these, the atharangi is the most common.

The themes used vary from common decorations to figurative representations of the Ramayana, the 10 incarnations of Vishnu, and gods and goddesses of Hindu mythology. They vary from region to region and are in Odissi style.

There are eight suits in a pack of cards, each one recognizable by a distinct background color. Each suit has 10 numbered cards and a king and vizier. The king is the highest in value with the vizier coming next, followed by the series in descending order. The king is distinguished as either sitting, or with legs folded at the knees, while the vizier is depicted standing.

Sometimes, the king is on a chariot and the minister mounted on a horse. In some other sets, the king is recognized by his two heads, while the minister is shown with one head. Somewhere on the card is another head of an animal. Eka, Douka, Teeka, Chouka, Pancha, Chhaka or Atha are the numbers of the cards. The horse, rat, Ganesha, Kartika, lotus or fish are the figures generally used.

Exotic Ganjapa cards were popular while luxury cards engraved on plates of wood were exclusive.

Making a Ganjapa card is an art that resembles pata chitra. A piece of cloth is dipped several times in a glue made of tamarind seeds and then dried to make it crisp. Circles are cut out of the cloth with a hollow iron cylinder. Two such circles of cloth, or a circle each of cloth and paper are pasted together. Finally a paste of chalk powder is applied. After this has dried, paints made from lac dye are used to make a base for painting. Cards are hand-printed.

The cards are mainly done by the women folk of artisan families. They prepare the cloth sheets, tamarind glue and traditional color and lacquer paste at home. Male artists traditionally paint figures on the cards.

Colors are used to distinguish the figures. For instance, in the Dasavatara series, blue is used to depict Vishnu avatara (the incarnation of Vishnu). Green personifies Rama, with red as a background color. In Matsya avatara, white is used for the figure (fish) with black as a background color. Kuchha avatara is shown in green, with background yellow as a contrast color.

Source: Ria/Ce

Animal Eyes

There’s a lot that can be inferred from looking at someone’s eyes. After all, they are the windows to the soul. But when it comes to animals, you can learn a lot more about them than just their personality.

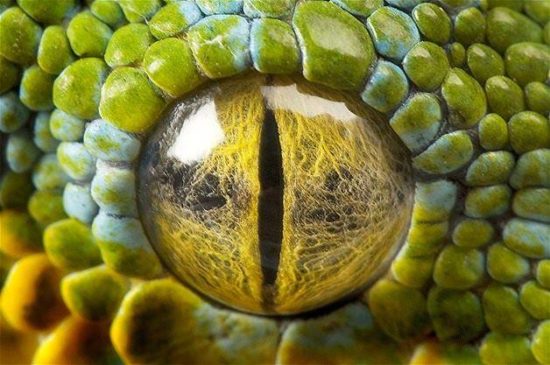

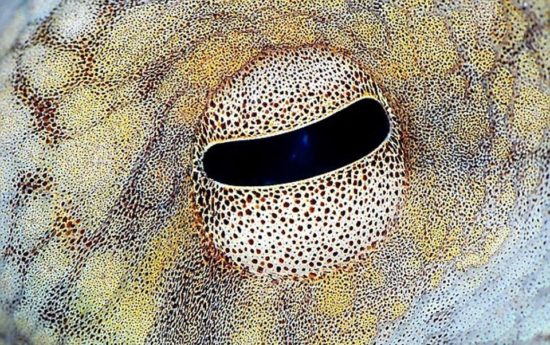

These animals all have unique, highly specialized eyes. Can you guess which animal each belongs to without reading the caption?

Cats can see 8 times better than humans.

Because geckos are nocturnal, their eyes are more light-sensitive, with the pupils constricting when they hit light.

A crocodile’s eyes can adapt to twilight or nighttime.

Penguins have eyes that allow them to see better underwater.

Chameleons can rotate their eyes 360 degrees independently of one another!

A python’s eye is mesmerizing.

A tokay gecko has transparent eyelids.

This tomato frog has many different types of optic nerves.

Marine mammals, like this whale, have limited vision because of the way the water refracts light.

Owls cannot easily see from close distances, but they are excellent from farther away, particularly in low light.

The octopus has binocular vision.

Just like humans, chimpanzees have binocular vision.

Lemurs have such excellent night vision that they can still make out colors in almost complete darkness.

Macaws see everything in ultraviolet vision.

A chinchilla has truly striking eyes. It looks like a landscape!

A crow’s eyes almost look like they’re frosted over. Chilling.

Parrots’ ultraviolet vision allow them to see the maturation of fruits.

Unlike other birds, the athene noctua owl is able to blink one eye and turn its head three-quarters of its total rotation.

This hippo’s eye is adapted for nighttime.

Found at Honest To Paws

Stress and Sight

Like breathing, seeing is not something you need to do, rather it is something which you allow. Most people, however, do not appreciate that seeing is essentially a passive process. They strain to count the stars in the sky, to read the tiny print of newspapers, and to keep awake while studying organic chemistry long into the night. The conditions of civilized life place our minds and bodies under continual tension which blocks our ability to let seeing take place naturally.

The idea that poor eyesight is primarily a result of stress was pioneered by ophthalmologist William Bates, MD. The solution to our vision problems, according to Bates, is not to stop reading, or looking at the stars, or studying for an exam, but rather to relax the mental strain which supports the imperfect functioning of the eye in both near work and distant vision. Aldous Huxley was one of the many who succeeded in doing this. Relaxation is the key.

Here’s an exercise for relaxing the eyes:

Resting:

To relax your eyes is to relax your whole body. Since so much of our sensory input is visual, temporarily closing off this channel will almost immediately cause the rest of the body to slow down. Brain wave patterns change to a lower frequency as soon as the eyes are closed. Resting your eyes are an important way of reestablishing balance throughout the system and reducing unnecessary strain.

Palming:

This is a technique developed by Bates for relieving eye strain.

- Sit or lie down and take a few moments to breathe deeply.

- Now gently close your eyes.

- Place the palms of your hands over your eyes, with your fingers crossing over your forehead.

- Use memory and imagination to realize a perfect field of black. see it so black that you cannot recall anything blacker.

- Do not try to produce any experience. Simply allow the blackness to happen.

- Continue for 2 to 3 minutes, breathing easily.

- Remove your hands from your eyes, and open them slowly.

- Do this several times a day, or whenever you need to relax.

From The Wellness Workbook

About The Third Eye

The third eye is known as the gateway to higher consciousness. It may alternately symbolize a state of enlightenment. In Eastern and Western spiritual traditions, the third eye is known as the “inner eye”; the mystical and esoteric concept referring to the “ajna” chakra. The third eye is associated with clairvoyance, out-of-body experiences, visions, and precognition. People who have developed their third eye are known as “seers”.

Hinduism and Buddhism use the third eye as symbolism of enlightenment. It is referred to as “the eye of knowledge” in Indian tradition. East Asian and Indian iconography show the third eye as a dot, eye or mark on the forehead of deities and other enlightened beings. Hindus place a “tilak” between the eyebrows as a representation of the third eye.

There are two small organs in the brain known as the pituitary body and the pineal gland. Medical Science refers to the pineal gland as the “atrophied third eye.” It is said that neither of these glands are atrophied. These glands were once used in the past as a means for man to get in touch with the inner worlds, his way to ingress. These glands will again serve that purpose. Man will again possess the ability of clairvoyance by remembering how to establish a connection to the pineal gland and the pituitary body, but on a much grander scale by connecting the pineal gland and the pituitary body with the cerebrospinal nervous system. Once this is accomplished, it will be under the control of man’s will.

Activating the third eye can be accomplished through meditation. Mastering the art of meditation will help to activate the pineal gland and the pituitary body as well as teaching you to relax and open your mind to all possibilities. Once this is accomplished, clairvoyance is easily reached.

In the charkra systems, the third eye is the sixth chakra and is associated with the color indigo. This chakra is often referred to as the avenue to wisdom. Here we can tap into our own inner wisdom and help to put our own learning experiences into perspective. It is through this open brow chakra that we develop our intuition and receive visual images.

The third eye is the heart of spiritual work. Through the third eye you can communicate what you desire to know about the aspects of your life which have been hidden from you. There would be spiritual darkness without the third eye.

If you are looking to open and clear your third eye you must clean up the heart as most of the energy moving through the third eye comes from the heart. Practicing chakra meditaitons will help you to open and clear all chakras allowing the energy to flow.

The third eye is located in the geometric center of the brain. There is a correlation between this and the Great Pyramids in the center of the physical planet. It is located directly behind the eyes attached to the third ventricle. It controls various biorhythms of the body and is activated by light. The pineal gland “third eye” works harmoniously with the hypothalamus gland which directs thirst, sexual desire, hunger, and the biological clock which determines the aging process.

From: Token Rock

About The Eye of Providence

The Eye of Providence (or the all-seeing eye of God) is a symbol, having its origin in Christian iconography, showing an eye often surrounded by rays of light or a glory and usually enclosed by a triangle. It represents the eye of God watching over humanity (the concept of divine providence).

In the modern era, a notable depiction of the eye is the reverse of the Great Seal of the United States, which appears on the United States one-dollar bill.

The Eye of Providence is sometimes associated with Freemasonry, although it is a Christian symbol. Often in Freemasonry, however, it is shown with a cloud rather than a trinitarian triangle. The Eye first appeared as part of the standard iconography of the Freemasons in 1797, with the publication of Thomas Smith Webb’s Freemasons Monitor.

Here, it represents the all-seeing eye of God and is a reminder that humanity’s thoughts and deeds are always observed by God (who is referred to in Masonry as the Great Architect of the Universe). Typically, the Masonic Eye of Providence has a semi-circular glory below it. Sometimes this Masonic Eye is enclosed by a triangle.

Popular among conspiracy theorists is the claim that the Eye of Providence shown atop an unfinished pyramid on the Great Seal of the United States indicates the influence of Freemasonry in the founding of the United States.

However, common Masonic use of the Eye dates to 14 years after the creation of the Great Seal. Furthermore, among the members of the various design committees for the Great Seal, only Benjamin Franklin was a Mason (and his ideas for the seal were not adopted). Indeed, many Masonic organizations have explicitly denied any connection to the creation of the Seal.

Source: Wikipedia

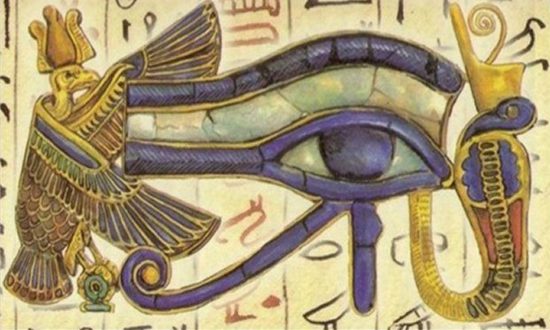

About The Eye of Horus

The Eye of Horus is an ancient Egyptian symbol of protection, royal power and good health. The eye is personified in the goddess Wadjet (also written as Wedjat, or “Udjat“, Uadjet, Wedjoyet, Edjo or Uto). It is also known as ”The Eye of Ra”.

The name Wadjet is derived from “wadj” meaning “green”, hence “the green one”, and was known to the Greeks and Romans as “uraeus” from the Egyptian “iaret” meaning “risen one” from the image of a cobra rising up in protection. Wadjet was one of the earliest of Egyptian deities who later became associated with other goddesses such as Bast, Sekhmet, Mut, and Hathor. She was the tutelary deity of Lower Egypt and the major Delta shrine the “per-nu” was under her protection. Hathor is also depicted with this eye.

Funerary amulets were often made in the shape of the Eye of Horus. The Wadjet or Eye of Horus is “the central element” of seven “gold, faience, carnelian and lapis lazuli” bracelets found on the mummy of Shoshenq II. The Wedjat “was intended to protect the pharaoh in the afterlife” and to ward off evil.

Ancient Egyptian and Near Eastern sailors would frequently paint the symbol on the bow of their vessel to ensure safe sea travel.

From: Wikipedia

The Eye As A Symbol

The symbolism of the eye occurs in so many places and in so many different forms that its pervasiveness symbolizes the “All Seeing Eye” itself.

The eye is closely associated with the idea of light and of the spirit, and is often called the “mirror of the soul.” When a person dies one of the first things that is done is that the eyes are closed, a timeless gesture that signifies the departure of the essence of life.

Generally, the right eye is considered to be the eye of the sun, the left, that of the moon.

The eye represents the “god within,” for example as the “third eye” whose position is designated by the small dot called the bindhu above and between the actual eyes. The Buddha is always depicted with this third eye. Here, the eye signifies the higher self, the part of man’s consciousness that is ego-free and can guide and direct him. whereas the eyes are organs of outward vision, this “eye of wisdom” directs its view internally as the “eye of dharma” or the “eye of the heart.”

As an occult symbol, the unlidded eye has its origins as the symbol of the Egyptian Goddess of Truth, Maat, whose name was synonymous with the verb “to see”; therefore the concepts of truth and vision were closely aligned.

The same eye symbol appears as the “Eye of Horus,” or Udjat. This stylized eye, with a brow above and featuring a curlicue underneath, represents the omnipresent vision of the Sun God Horus, and is a prominent symbol within the Western magical tradition where it represents, among other things, secret or occult wisdom. This eye was painted on the sides of Egyptian funerary caskets in the hope that it would enable the corpse to see its way through the journey to the Afterlife.

In Celtic magical lore, too, the eye equated with the Sun, and the planet and the eye shared the same name, Sul.

The All Seeing Eye, the eye within a triangle with rays emanating from the lower lid, is used not only in Freemasonry (where it stands for the “Great Architect of the Universe,” for external vision, and also for inner vision and spiritual watchfulness) but in Christian symbolism too.

The eye symbol is used as a charm, painted on the sides of humble fishing boats, in order to protect the boat from the evil eye and to somehow confer this inanimate object with the power of sight of its own, a notion which follows exactly the same reasoning behind the practice of the Egyptians painting eyes on the coffins of their dead.

Belief in the evil eye is ancient, referred to in Babylonian texts dating back to 3.000 years before Christ. This is the idea that some people can curse an object (or a person) simply by the act of looking, as though the eye itself can direct a malevolent thought. It is a mark of the profound belief in the concept of the evil eye that there are so very many charms said to protect against it.

About Madhubani Marriage Mandala Art

Perhaps the best known genre of Indian folk paintings are the Mithila (also called Madhubani) paintings from the Mithila region of Bihar state. For centuries the women of Mithila have decorated the walls of their houses with intricate, linear designs on the occasion of marriages and other ceremonies.

Perhaps the best known genre of Indian folk paintings are the Mithila (also called Madhubani) paintings from the Mithila region of Bihar state. For centuries the women of Mithila have decorated the walls of their houses with intricate, linear designs on the occasion of marriages and other ceremonies.

Painting is a key part of the education of Mithila women, culminating in the painting of the walls of the kohbar, or nuptial chamber on the occasion of a wedding. The kohbar ghar paintings are based on mythological, folk themes and tantric symbolism, though the central theme is invariably love and fertility.

The major part of the painting has a circle of yantras representing different gods and goddesses. It is the influence of Tantra on the religious scene. The Kali Yantra, Sri Yantra etc. form the conglomeration of yantras, akin to mandalas, a symbol in Tantric art. Around the yantras are depictions of marriage rituals.

On either side of this central motif are the faces of the bride and the bridegroom. The auspicious kalas, fish and turtle, symbolic of fertility are also painted around the outside of the mandala, as are symbols of prosperity and longevity such as the elephant, tree of life, and bamboo.

The bamboo tree, fish and turtle portrayed in the paintings point to the earthly pleasures which find culmination in marital relationship. The lion expresses male energy and the peacock, the female beauty; the fish and the turtle are symbols of proliferation and fertility.

These kohbar paintings often have a lotus motif pierced by a bamboo shaft representing sexual union of the bride and the bridegroom. Parrots, which represent the lovers, are often painted around the rim of the central lotus mandala.

The lower half of the painting is usually narrative in nature, showing the couple performing various religious ceremonies. Here, too, are painted images of the bridegroom in a palanquin followed by another one carrying the bride to his home.

These kind of kohabar pictures abound on the walls of Madhubani villagers, which are later layered and pictures of other auspicious objects appear once the marriage rituals are over.

The contemporary art of mithila painting was born in the early 1960’s, following the terrible Bihar famine. The women of Mithila were encouraged to apply their painting skills to paper as a means of supplementing their meager incomes. Once applied to a portable and thus more visible medium, the skills of the Mithila women were quickly recognized. The work was enthusiastically bought by tourists and folk art collectors alike. As with the wall paintings, these individual works are still painted with natural plant and mineral-derived colors, using bamboo twigs in lieu of brush or pen.

Over the ensuing forty years a wide range of styles and qualities of Mithila art have evolved, with styles differentiated by region and caste – particularly the Brahmin, Kayastha and Harijan castes. Many individual artists have emerged with distinctive individual styles.