Fairies

The Tale of the Tontlawald

Long ago, in the midst of a country covered with lakes stood a vast stretch of moorland called the Tontlawald, on which no man ever dared set foot. From time to time a few bold spirits had been drawn by curiosity to its borders, and returned with tales of a ruined house in a grove of thick trees, and round about it were a crowd of dirty, ragged men, old women and half-naked children.

One night a peasant returning home from a feast wandered into the Tontlawald, and came back with the same story. A countless number of women and children were seated round a huge fire while others danced on the grass. One old crone had a broad iron ladle in her hand; every now and then she stirred the fire, but the moment she touched the glowing ashes the children rushed away shrieking and it was a long while before they ventured back again.

Once or twice a little old man with a long beard had crept out of the forest, carrying a huge sack. The women and children ran by his side, weeping and trying to drag the sack from off his back, but he shook them off, and went on his way.

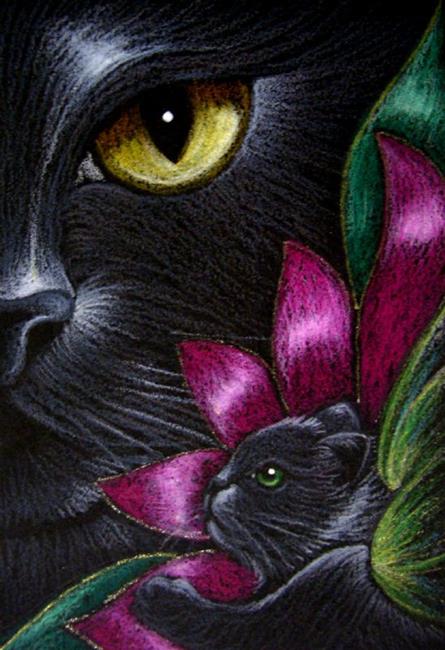

There was also a tale of a magnificent black cat as large as a foal, with teeth like daggers and eyes that shone red like burning coals, but men could not believe all the wonders told by the peasant, and it was difficult to make out what was true and what was false in his story, since he had drunk plenty of beer at the feast before wandering onto the Tontlawald. Nevertheless, strange things did happen there, and though the king gave orders to cut down the haunted wood, no one was ever brave enough to do so. A brave man had once struck his axe into a tree, but his blow was followed by a stream of blood and shrieks like a human creature in pain. The terrified woodcutter had fled as fast as his legs would carry him, and after that neither orders nor threats would drive anybody to the enchanted moor.

A few miles from the Tontlawald was a large village. A peasant there had recently married a young wife who had turned the whole house upside down, and the two quarreled and fought all day long. The peasant’s first wife had given him a daughter called Elsa; she was a good quiet girl, who only wanted to live in peace, but her stepmother beat the poor child from morning till night and the peasant was too scared of his wife to do anything to stop the ill-treatment.

For two years Elsa suffered all this ill-treatment, then one day she went strawberry-picking with the other village children. They wandered carelessly to the edge of the Tontlawald, where they found the finest strawberries. The children ate as many strawberries as they could, wandering further and further into the Tontlawald, until suddenly one of the older boys cried out “Run, run as fast as you can! We are in the Tontlawald!”

The children ran madly away, all except Elsa, who had strayed farther than the rest into the Tontlawald and did not want to give up picking the fine strawberries she had found. “The dwellers in the Tontlawald cannot be any worse than my stepmother,” she said to herself, and besides she was very hungry as her stepmother didn’t give her enough to eat.

Elsa looked up and saw a little black dog with a silver bell on its neck come barking towards her, followed by a maiden clad all in silk. The girl told the dog to be quiet then turned to Elsa and said “I’m so glad you didn’t run away with the others. Stay here and be my friend, – we will play delightful games together and gather strawberries every day. No-one will dare to beat you if I tell them not. Come, let us go to my mother.”

Taking Elsa’s hand she led her deeper into the wood, the little black dog jumping up beside them and barking with pleasure. Elsa was astonished at the wonders and splendors before her. Trees and bushes stood before them, overburdened with fresh ripe fruit; bright birds darted among the branches and filled the air with song. The birds were not shy, but let the girls take them in their hands, and stroke their gold and silver feathers. In the center of the garden, a house shone with glass and precious stones, and in the doorway sat a woman in rich garments.

The woman who turned to Elsa’s companion and asked, “Daughter, what sort of a guest have you brought to me?”

“I found her alone in the wood,” replied her daughter, “and brought her back as a companion. Will you let her stay?”

The mother laughed, but said nothing. She looked Elsa up and down sharply then stroked her cheeks kindly and asked if her parents were alive, and if she really would like to stay with them. Elsa stooped and kissed her hand, then, kneeling down, buried her face in the woman’s lap.

Elsa sobbed to the woman “My mother died many years ago. My father is still alive, but doesn’t care about me and his new wife, my stepmother, beats me all the day long. I can do nothing to her satisfaction, so please let me stay with you. I will look after the flocks or do any work you tell me. I will obey you, only please do not send me back to her. She will half kill me for not having come back with the other children.”

The woman answered, “We’ll see what we can do with you,” and went into the house.

The daughter said, “Don’t be afraid, I can tell by the way she looks at you that my mother will be your friend,” and she told Elsa to wait while she went into the house to speak with her mother.

Half-afraid and half-hopeful, Elsa waited for her strange new friend to return. At length the girl returned holding a box in her hand and said that they could play together while her mother decided what must be done. “Have you ever been on the sea?” she asked.

“The sea?” asked Elsa, “I’ve never heard of such a thing!”

“I’ll soon show you,” answered the girl, opening the box.

At the bottom of the box lay a scrap of a cloak, a mussel shell and two fish scales. Two drops of water were glistening on the cloak and the girl shook the water onto the ground. In an instant, everything had vanished and as far as the eye could reach Elsa could see nothing but water. Only under their feet was a tiny dry spot. Then the girl placed the mussel shell on the water and took the fish scales in her hand.

The mussel shell grew bigger and bigger, and turned into a small boat, large enough for several children to sit in. The girls stepped in, Elsa very cautiously, and her friend used the fish scales for a rudder. The waves rocked them softly, as if they were lying in a cradle, and they floated on till they met other boats filled with merry, singing men and the girl sang back to them, in a strange language. Elsa noticed they sang the word “Kisika” over and over and this turned out to be the girl’s name.

Though they felt they could have played on the sea forever, by and by they heard a voice calling them home. Kisika took the little box out of her pocket, with the piece of cloth inside it, and dipped the cloth in the water. They were back where they had started, standing on firm, dry land close to the splendid house in the middle of the garden. Kisika put the mussel shell and fish scales back in the box and the girls went inside the house. They entered a large hall, where twenty-four richly dressed women were sitting round a table as if for a wedding feast. At the head of the table sat the lady of the house in a golden chair.

Elsa did not know which way to look. She sat down with the others and ate some delicious fruit while the women talked softly in a language she did not understand. At length the hostess turned round and whispered something to a maid behind her chair. The maid left the hall and returned with a little old man whose beard was longer than himself. He bowed low to the lady and then stood quietly near the door.

“Do you see this girl?” said the lady of the house, pointing to Elsa. “I wish to adopt her for my daughter. Make me a copy of her, which we can send to her home to take her place.”

The old man looked Elsa all up and down, as if he was taking her measure, then bowed to the lady and left the hall.

After dinner the lady said kindly to Elsa, “Kisika has begged me to let you stay with her, and you have told her you would like to live here. Is that so?”

Elsa fell on her knees at the lady’s feet in gratitude for her escape from her cruel stepmother, but her hostess raised her from the ground and patted her head, saying, “All will go well as long as you are a good, obedient child. I will take care of you and see that you want for nothing till you are grown up and can look after yourself. You will be schooled with my own daughter, Kisika.”

Not long after the old man came back with a mold full of clay on his shoulders and a little covered basket in his left hand. He put down his mold and his basket on the ground, took up a handful of clay, and made a doll as large as life. When it was finished he bored a hole in the doll’s breast and put a bit of bread inside. Then, drawing a snake out of the basket, he forced it to enter the hollow body.

“Now,” he said to the lady, “all we want is a drop of the maiden’s blood.”

“Don’t be afraid,” said her hostess, “this is not for any bad purpose, but rather to give you freedom and happiness.”

She took a tiny golden needle, pricked Elsa in the arm and gave the blood-stained needle to the old man, who stuck it into the heart of the doll. When this was done he placed the figure in the basket, promising that the next day they should all see what a beautiful piece of work he had finished.

When Elsa awoke the next morning in a soft feather bed to see a beautiful dress lying over the back of a chair, ready for her to put on. A maid combed out her long hair, and brought the finest linen for her use. The thing that gave Elsa the greatest joy was the little pair of embroidered shoes, for her stepmother had always made her go barefoot. In her excitement, she gave no thought to the rough clothes she had worn the day before; they had disappeared as if by magic. The living doll, now full grown and identical to Elsa, had been dressed in her old clothes and had gone back to the village in Elsa’s place. When Elsa saw the doll, she was both astonished and frightened.

“Don’t be frightened,” said the lady, when she noticed Elsa’s terror, “this clay figure can do you no harm. It is for your stepmother, that she may beat it instead of you. Let her flog it as hard as she will since it can never feel any pain. And if the wicked woman does not come one day to a better mind, your double will be able at last to give her the punishment she deserves.”

From that moment on, Elsa’s life was that of an ordinary happy child and she began to forget the mistreatment at her stepmother’s hands. The happier she grew, the deeper was her wonder at everything around her and the more firmly she was persuaded that some great unknown power must be at the bottom of it all.

In the courtyard stood a huge granite block about twenty steps from the house. At meal times, the long-bearded old man went to the block, drew out a small silver staff, and struck the stone three times, so that the sound could be heard a long way off. At the third blow, out sprang a large golden cock, and stood upon the stone. Whenever he crowed and flapped his wings the rock opened and something came out of it.

First came a long table covered with dishes ready laid for the number of persons who would be seated round it; this flew into the house all by itself. When the cock crowed for the second time, a number of chairs appeared, and flew after the table; then wine, apples, and other fruit, all without trouble to anybody. After everybody had had enough, the old man struck the rock again. The golden cock crowed afresh, and back went the dishes, table, chairs, and plates into the middle of the block.

When, however, it came to the turn of the thirteenth dish, which nobody ever wanted to eat, a huge black cat the size of a foal, with pearl-white teeth and brilliant orange eyes ran up and stood on the rock close to the cock, while the dish was on his other side. There they all remained, till they were joined by the old man. He picked up the dish in one hand, tucked the cat under his arm, told the cock to get on his shoulder, and all four vanished into the rock.

This wonderful stone contained not only food, but clothes and everything they could possibly want in the house. Over time, Elsa learnt to understand the strange language spoken at mealtimes though it took her years to learn to speak it. One day she asked Kisika why the thirteenth dish came daily to the table and was sent daily away untouched, but Kisika knew no more about it than she did. The girl asked her mother and a few days later her mother spoke to Elsa seriously about the thirteenth dish.

“The thirteenth dish is the dish of hidden blessings. If we ate it, our happy life here would come to an end. The world would be a great deal better if greedy men did not seek to snatch every thing for themselves, instead of leaving something as a thanks offering to the giver of the blessings. Greed is man’s worst fault.”

The years passed quickly, for there were always things to occupy the days, and Elsa grew into a lovely woman, with a knowledge of many things that she would never have learned in her native village. However, Kisika was still the same young girl that she had been on the day of her first meeting with Elsa and wanted to play childish games and complained that Elsa had grown too big for games. One day, after nine years, the lady called Elsa into her room. Elsa’s heart sank when she saw the lady’s eyes full of tears.

“Dearest child,” she said, “you have grown into a woman and the time has come when we must part.” Elsa begged to stay, perhaps as a maidservant to the gracious lady, but the lady said, “My child, it is time for you to return to the world of men, where joy awaits you.”

“Please don’t cast me out into the world. It would have been better if you had left me with my stepmother, than to have brought me to heaven and then send me back to a worse place.”

“Do not talk like that, dear child,” replied the lady sternly, but kindly, “You are a mortal, and unlike us you are growing older. Surely you’ve noticed that Kisika never ages? It’s hard for me to let you go, but it is your destiny to have a husband and raise children.”

Back in Elsa’s home village, her stepmother had beat the Elsa doll night and day, though of course the doll felt no pain. When Elsa’s father tried to stop her, the stepmother beat him as well. One day, in a rage, the stepmother had grabbed the Elsa doll by the throat and tried to throttle it. The snake came out from the doll’s mouth and bit the woman’s tongue, killing her at once. When Elsa’s father came home, he found his wife’s body swollen and disfigured and Elsa was gone. His neighbors had heard a commotion, but that was quite normal and they had taken no notice.

Pleased to be free of his ill-tempered wife, he prepared her body for burial. Then, quite tired, he ate the piece of bread he found lying on the kitchen table. The next day, his neighbors found him sitting at the table, his face and body as disfigured as that of his wife and he was buried with his nagging wife. Everyone supposed that Elsa had finally fled from the beatings.

The morning Elsa was to leave, the lady placed a gold seal ring on Elsa’s finger then strung a little golden box on a ribbon and placed it round her neck. The old man touched Elsa softly on the head three times with his silver staff. In an instant Elsa was transformed into an eagle. For several days she flew steadily south, neither tired nor hungry. One day as she flew over a dense forest, she heard hounds barking at her and then a sharp pain in her breast. The Elsa-eagle fell to the ground, pierced by an arrow. However, when Elsa recovered her senses, she found herself lying under a bush in her own proper form, quite uninjured.

As she was wondering what had happened, the king’s son came riding by. Seeing Elsa, sprang from his horse, and took her by the hand, saying, “My lady, every night, for half a year, I have dreamed of finding you in this wood. I have searched it hundreds of times in vain and never given up hope. Today I was going in search of a large eagle that I had shot, but instead of the eagle I find the lady of my dreams!” He took Elsa on his horse, and rode with her to the town, where the old king received her graciously.

A few days later Elsa and the prince were married. The lady of the Tontlawald sent fifty carts laden with beautiful things to their wedding. In time, Elsa became queen of that land, but nothing more was ever heard of the Tontlawald nor of the fiery-eyed cat as big as a foal.

From: Moggy Cat

Cats and Baby’s Breath

Long, long ago in parts of Europe, it was believed that fairy folk stole babies from their cribs and left in their place a fairy child. They were called changelings and were unhappy in the human world. A fairy child grew up wild and fey, always looking for a way back into the Summerlands; its green or blue eyes were slanted a little and its ears were a little more pointed than normal. And a changeling had a strange way of looking at the world, as though looking through the world to something hidden beyond.

But how? I hear you ask. How could fairies steal away babies?

Long ago, when fairies walked invisible in the world, only cats could see the fey folk. When a cat sat silently watching and there was nothing there to see, it was watching the fairies about their business. And when a cat sat on a mother’s lap, the sound of the cat’s purring was the sound of it spinning sleep so that the fairies could steal away her child to be their toy.

The purr was like the sound of spinning wheels steadily spinning and that’s what it was – as humans slept in an enchanted sleep spun by a purring cat, the fairies stole away the human infant and left one of their own in its place.

It was in the cat’s nature to be attracted to a changeling infant and to suck its breath as payment for spinning sleep. So at night, the cat settled down in the changeling’s crib and sucked the changeling baby’s warm milky breath. Sometimes a greedy cat stole too much of the baby’s breath and the parents grieved over the child, not realizing that their own baby had been stolen away long time before.

The ancient compact between cats and fairies ended long time ago when the wise cats realized that humans offered a far more comfortable home. Cats still sit and watch fairies about their invisible business, but they no longer spin sleep so that fairies can steal away human children to be their toys. Cats still like the warmth of a baby’s crib and are still accused of stealing a baby’s breath.

And of course, cats still purr like steady spinning wheels. When a cat is contented it purrs to itself in satisfaction, knowing that it has a far better compact with human folk than with fairy folk. In modern times, a cat only spins sleep if you let it.

From: Moggy Cat