Winter Solstice

Yes you can have a family Yule celebration and still have a holiday tree, and hang stockings with care by the fire.

During the Roman festival of Saturnalia, celebrants often decorated their homes with clippings of shrubs, and hung metal ornaments outside on trees. Typically, the ornaments represented a god — either Saturn, or the family’s patron deity. The laurel wreath was a popular decoration as well. The ancient Egyptians didn’t have evergreen trees, but they had palms — and the palm tree was the symbol of resurrection and rebirth. They often brought the fronds into their homes during the time of the winter solstice.

Early Germanic tribes decorated trees with fruit and candles in honour of Odin for the solstice. These are the folks who brought us the words Yule and wassail, as well as the tradition of the Yule Log!

In other words, if you want to have a decorated tree for the holiday, don’t let anyone tell you it doesn’t have Pagan origins. And if you’d like to go for a more authentic pagan look, there are a ton of other things out there you can use.

Here are some ideas:

- Suns and solar ornaments – raid the craft stores and find stars to turn into suns

- Gods Eyes – make then out of cinnamon sticks and seasonal coloured yarn or ribbons

- Pentacles – make them out of shiny chenille stems, bent into stars with circles around them

- Natural objects like acorns, feathers, holly, mistletoe or pine cones

- Lights, lights, and more lights

- Magical items – cups, wands, or daggers

- Fertility symbols – eggs, antlers, horns

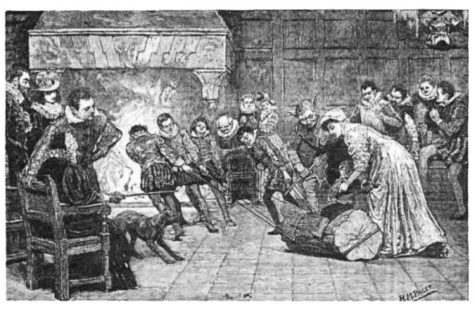

On the winter solstice, on the longest night of the year, people would place and set afire an entire tree, that was carefully chosen and brought into the house with great ceremony. The largest end of the log would be placed into the fire hearth while the rest of the tree stuck out into the room! The log would be lit from the remains of the previous year’s log which had been carefully stored away and slowly fed into the fire through the Twelve Days of Christmas.

It was considered important that the re-lighting process was carried out by someone with clean hands.

Tradition has it that the burning of the Yule log was performed to honor the Great Mother Goddess. The log would be lit on the eve of the solstice using the remains of the log from the previous year and would be burned for twelve hours for good luck and protection.

As the fire began all other lights would be extinguished and the people would gather round the fire. In thanksgiving and appreciation for the events of the past year and in bidding the year farewell each person would toss dried holly twigs into the fire.

The next phase of the burning of the Yule log commenced with people tossing oak twigs and acorns into the fire and they would shout out their hopes and resolutions for the coming New Year and sing Yuletide carols. The celebration of the Yule log fire ended with unburned pieces of the Yule log saved to start the fire of next winter’s solstice Yule log.

The custom of the Yule Log spread all over Europe and different kids of wood are used in different countries. In England, Oak is traditional. The “mighty oak” was the most sacred tree of Europe, representing the waxing sun, symbolized endurance, strength, protection, and good luck to people in the coming year. In Scotland, it is Birch; while in France, it’s Cherry. Also, in France, the log is sprinkled with wine, before it is burnt, so that it smells nice when it is lit.

The earliest Yule Log in France can be traced back to Celtic Brittany. When the Catholic Church stamped out the Pagan tradition, it adapted. In the 12th century, the ceremony became more elaborate.

Families would haul home enormous logs and in some regions, the youngest child was allowed to ride the log home. As families dragged their logs home, passers by would raise their hats because they knew the log was full of good promises and its flame would burn out old wrongs.

For the Vikings, the yule log was an integral part of their celebration of the solstice, the julfest; on the log, they would carve runes representing unwanted traits (such as ill fortune or poor honor) that they wanted the gods to take from them.

People would also use the log as a way to predict events in the upcoming year. They would hit the burning log with tongs and the embers emitted would tell them what the harvest would be like. The more embers, the more corn. The fire was read and predictions were made for the coming year based on the sparks and flames they saw, like how many chickens or calves would be born, marriages in the family, health, wealth, etc. If the fire cast shadows on the wall, there would be a death in the family that year.

The remaining cinders would be placed in the soil so they would prevent grain diseases and produce a good harvest. They’d be spread around chicken coops to keep away foxes and in the barns and lofts where corn was stored to keep rats and weevils away. During a storm, throwing a handful into the fire would keep the house safe from lightening.

The ashes of the Yule Log were believed to hold magical and medicinal powers that would ward off evil spirits for the coming year. Ashes from the Yule log are very beneficial to garden plants, however, it is considered very unlucky to throw out the ashes of the Yule log on Christmas day.

Various chemicals can be sprinkled on the log like wine to make the log burn with different colored flames! Here’s a short list. Be sure to follow safety precautions if you plan on using them!!

- Potassium Nitrate = Violet

- Barium Nitrate = Apple Green

- Borax = Vivid Green

- Copper Sulphate = Blue

- Table Salt = Bright Yellow

The Inti Raymi (Quechua for “sun festival”) is a religious ceremony of the Inca Empire in honor of the god Inti (Quechua for “sun”), one of the most venerated deities in Inca religion. It was the celebration of the winter solstice – the shortest day of the year in terms of the time between sunrise and sunset and the Inca New Year.

Note:

In territories south of the equator the gregorian months of June and July are winter months. It is held on June 24.

During the Inca Empire, the Inti Raymi was the most important of four ceremonies celebrated in Cusco. The celebration took place in the Haukaypata or the main plaza in the city.

According to chronicler Garcilaso de la Vega, Sapa Inca Pachacuti created the Inti Raymi to celebrate the new year in the Andes of the Southern Hemisphere. The ceremony was also said to indicate the mythical origin of the Incas. It lasted for nine days and was filled with colorful dances and processions, as well as animal sacrifices to thank Pachamama and to ensure a good cropping season.

The first Inti Raymi was in 1412. The last Inti Raymi with the Inca Emperor’s presence was carried out in 1535, after which the Spanish and the Catholic priests banned it.

In 1944, a historical reconstruction of the Inti Raymi was directed by Faustino Espinoza Navarro and indigenous actors. The first reconstruction was largely based on the chronicles of Garcilaso de la Vega and only referred to the religious ceremony. Since 1944, a theatrical representation of the Inti Raymi has been taking place at Saksaywaman, two kilometers from its original celebration in central Cusco on June 24 of each year, attracting thousands of tourists and local visitors.

Inti Raymi is still celebrated in indigenous cultures throughout the Andes. Celebrations involve music, colorful costumes (most notable the woven aya huma mask) and the sharing of food.

Inti Raymi is still celebrated in indigenous cultures throughout the Andes. Celebrations involve music, colorful costumes (most notable the woven aya huma mask) and the sharing of food.

In many parts of the Andes though, this celebration has been connected to the western festivals of Saint John the Baptist, which falls on the day after the northern solstice (June 21).

Also known as Mithras (for the Persian Sun God), Saturnalia (for the Roman God of sowing and husbandry) and The Great Day of the Cauldron (from Druid Legend). It is the celebration of the return, or rebirth, of the Sun God, the Lord of Life. The celebrations were traditionally performed with the utmost solemnity, yet also with the highest rejoicing, for they resolve the paradox of Death and Rebirth. It represents the redemption of the world from Death and Darkness, as such it is a celebration of hope and joy amidst the gloom of winter.

The word Yule can be traced to the Celtic word `Hioul” which means wheel. This festival is an important point in the turning of the wheel of the year. Wreaths were made to symbolize this wheel, combining solar significance with tree-god significance. In ancient times Celts venerated trees as earthly representatives of the Gods, and it was felt that nothing short of the sacrifice of a mighty tree-god would cause the receding sun to take pity on them and return.

The burning of the Yule log was thought, through sympathetic magick, to increase the brightness and strength of the Sun, and would therefore bring good luck. Passersby would tip their hat or nod in salutation to the log. It is traditional to cut the log from oak or from a slow-burning fruit tree. The fire was lit from a piece of the previous years Yule log, which had been saved for this purpose. It was believed that this piece of the old log was a charm against fire, because it would refuse to burn until it was time to light its successor. A wish was also made while pouring wine over the burning log. It was believed to be bad luck if the log burned out before the 12 days of Yuletide were over. The ashes from the fire were spread in the fields to bring fertility to the next crop.

The Wassail bowl is another favored part of Yule celebrations. A large bowl or pot was filled with wassail, a mixture of cider and spices, and warmed over the Yule fire. The meaning of the word wassail is to be `hale or hearty’, and was the reason for the many toasts and salutations made from the bowl. It was also common for a procession to go to the nearest orchard and wassail the trees, thus blessing them and encouraging them to bear a good yield in the coming season. Libations of wassail were also poured over the roots of the trees, and cider drenched cakes were left in the forks of the older trees as an offering to the trees spirit.

Mistletoe is a regeneration symbol, considered to be the Essence of Life due to the resemblance of the juice of the berries to male semen. It was often gathered at this time. Evergreen boughs are also symbols of renewal. Evergreens were decorated to show honor to the tree spirits. The lights on modern trees were the candles of old, and represent the newly born sun god. Trees were not cut down and brought indoors.

The Sacred Seed of Life, having been nurtured by the foster mother Tailltiu, sprang forth from her breast, and was born. As the Wyrrd had foretold, here was the Child of Promise, son of the Gods and of the Earth. This baby was the Sun God, born in the Rule of Darkness, by the magick of the Gods. He was destined to grow in strength and knowledge. It was his task to bring back life and warmth to the land, and to wrest the power from the Lord of Darkness. To appease Cernunnos, who is at the peak of his strength, the people made sacrifices of roasted boar. To distract Callieach, the Wise Ones, or Witches invoked her to teach them of her mysteries. To aid the new-born Sun God the Celts felled a giant oak tree, and burned the log as a sacrifice, that the sun would gain strength from it, and grow.

Despite the powers of Cernunnos and Cailleach, the signs of new life were still upon the land. The sacred seeds which had fallen onto the barren branches of the winter-dead trees had come to life, and thus became the Mistletoe, which could be seen hanging from the oaks in the forests. Upon the land these sacred seeds had grown into the sweet smelling evergreens, and thus they were decreed to be a part of the celebration.

In honor of this magickal birth the people decorated the evergreens with candles and other symbols of life. The Druids told of Hu-Gadarn, the first druid, who had fled from the Atlalntean flood with his family on this day on the Ark, “The Great Cauldron” in which they brought the Essence of Life, and the knowledge of magick into the world. They would also tell tales of the Killing of the Wren, and of the Battle between the Oak King and the Holly King. Throughout the land the people rejoiced, and there was light in the midst of the darkness.

Blessed Be

~Lady Galadriel

Saturnalia was an ancient Roman festival in honor of the deity Saturn. Originally it was held on 17 December of the Julian Calendar, but the party later expanded with festivities through to 23 December. The poet Catullus called it “the best of days”.

Saturn being an ancient national god of Latium, the institution of the Saturnalia is lost in the most remote antiquity. In Roman mythology, Saturn was an agricultural deity who was said to have reigned over the world in the Golden Age, when humans enjoyed the spontaneous bounty of the earth without labor in a state of innocence. The revelries of Saturnalia were supposed to reflect the conditions of the lost mythical age, not all of them desirable. The Greek equivalent was the Kronia.

Falling towards the end of December, at the season when the agricultural labors of the year were completed, it was celebrated by the country-people as a sort of joyous harvest home, and in every age was viewed by all classes of the community as a period of absolute relaxation and unrestrained merriment. The festival was extended in later times to three and still later to seven days.

During the celebration of this holiday no public business could be transacted, the courts were closed, war was suspended, all private enmities were for the time forgotten, and the city was alive with hilarity. On this day the slaves feasted and were waited upon by their masters, as the female slaves were waited upon by their mistresses on the Matronalia.

The special feature of the festival was the gift of wax candles and of little images of wax or clay called sigilla. The public festival, in the time of the republic, was for only one day; but for seven days the celebration continued in private houses.

Many of the customs of the Roman Saturnalia were taken over by the Christian Church in celebrating Christmas. Thus the origin of the Christmas-tree, and the custom of making presents to children and friends may be traced back to the Roman Saturnalia, while the Yule-log and Yule-fire are remnants of ancient sun-worship, one of the Roman festivals in honor of the Sun god being celebrated on the 25th of December as “Dies Natalis Solis Invicti.”

Although probably the best-known Roman holiday, Saturnalia as a whole is not described from beginning to end in any single ancient source. Modern understanding of the festival is pieced together from several accounts dealing with various aspects.

Here’s some History:

Saturnalia festivities began with ritual and sacrifices in the Temple of Saturn. The statue of the god was hollow and filled with olive oil, as a symbol of his agricultural functions. His feet were bound with woolen strips, that were unbound at Saturnalia.

After the rituals, the Senators (who had to be present) dismissed the crowd with the cry of “Io, Saturnalia!”, a sign for the happy festivities of family parties and other private gatherings to begin. The traditional gifts were wax tapers and little dolls, although gifts of silver later became traditional.

The custom of the Lord of Misrule was appropriated and survived through to English Christmas traditions.

The biggest part of Saturnalia was attitude more than decoration. Feasting, drunkenness, merrymaking, hopefully the conception of more children (or at least enjoying those activities which led to conception!), pranks, gift giving, role reversals (not true ones, only symbolic ones – slaves weren’t really free to make a freedman’s decisions and anything they did or decreed would reverse at the end of Saturnalia, children weren’t really adults and could not enter into any binding contracts or make business deals, etc.) and so forth.

The role reversals seemed to be more for minor privileges – slaves and children got to be waited on for meals, and to lead the rituals, and to participate in the revelry as if they were their parents/masters. The parents/masters jokingly played the part of slaves and children by waiting on them and making rude and bawdy jokes at their expense. Sometimes, it descended into cruelty.

Many of the decorations involved greenery – swathes, garlands, wreaths, etc – being hung over doorways and windows, and ornamenting stairs. Ornaments in the trees included sun symbols, stars, and faces of the God Janus. Trees were not brought indoors (the Germans started that tradition), but decorated where they grew.

Food was also a primary decoration – gilded cakes in a variety of shapes were quite popular, and children and birds vied for the privilege of denuding the trees of their treats. The commonest shapes were fertility symbols, suns and moons and stars, baby shapes, and herd animal shapes (although, to be honest, it’s hard to tell if some of those ancient cookie cutters are supposed to be goats or deer). I would imagine coins were also a popular decoration/gift.

People were just as likely to be ornamented as the trees. Wearing greenery and jewelry of a sacred nature was apparently common, based on descriptions, drawings, and the like from the era. Although the emphasis was on Saturn, Sol Invictus got a fair share of the revelry as well.

On a modern note:

This ancient midwinter festival falls at the time when non-Romans are celebrating Christmas, Hanukkah, Solstice and/or Kwanzaa. In Nova Roma, individual Citizens have chosen different approaches to the challenge of celebrating in the spirit of Rome without cutting themselves off from the culture in which they live.

Gold, because the sun is yellow, is always a sure choice for a good Saturnalia decoration. For modern Saturnalia, those golden glass ball ornaments are ideal, as are gold sun faces, gold stars, and gilded anythings. Gilding nuts and pine cones and nestling them among the swags and wreaths of greenery would be a lovely way of acknowledging the ancient roots of this ceremony.

Indoor trees are not ancient Roman, but if you have plants growing indoors, decorating them would certainly be in the spirit of the holidays. If you just have to have the now-traditional indoor tree, try decorating it in gold ornaments with a solar theme. Swathe it in bright red or purple ribbons (2 colors quite in favor with the Romans, and looks great with the gold ornaments). Top the tree with a sun, rather than a star, for after all, this is a solar celebration.

Wild parties with lots of food and drink is good. Letting the children of the household lead the common rituals, and waiting on them (assuming you don’t do so in everyday circumstances….) at mealtimes, and deferring to them in decisions on party ideas would work for role reversals.

No children in the house? Maybe you can borrow one for a day. We don’t have slaves, but, for a nice touch of role reversal, we could purchase the services of a nanny or a housekeeper for the duration of Saturnalia. It would be a role reversal of sorts, for instead of being the slave of your home, someone else would be doing the chores and cooking and childcare while you got to party down!

Dancing and singing in the streets is now frowned upon, unless you can get a parade permit. A parade, if you could organize it, would be fun. Imagine – giant floats of the Gods tended by the priests and acolytes, musicians and dancers, contortionists to amaze and delight, acrobats and jugglers, all in honor of Saturn!

For a compilation of Saturnalia celebrations reported by Nova Romans, visit Saturnalia practices of Nova Romans.

Here is a nice little article about the history of midwinter celebrations from Delaware Online:

Ancient Worship:

Long ago, people worshiped the sun as a god. His cycles were watched and measured with great care because it was thought the quality of life on Earth changed dramatically according to his whims.

As the season changed and winter fell, survival became much harder for ancient man. Many would not live through a cold winter, when food became scarce. As the days shortened, they feared the sun would disappear completely and leave them helpless in the dark.

So they lighted fires and performed elaborate rituals to ensure the sun’s return. They also feasted when the sun reversed its course, and days began to grow long again.

One of the earliest solstice celebrations was the Mesopotamian holiday Zagmuk. When light waned in mid-winter, Mesopotamians would re-enact their god Marduk’s battle against the forces of darkness and chaos and then celebrate the victory of light and order.

More than 4,000 years ago, ancient Egyptians called their sun god Ra-Horakhty, later known as Horus. As winter arrived and his appearance became more brief each day, it was seen as a sign that he was growing weak and ill. In late December, when days began to grow longer, they celebrated his recovery and renewed health. They decked their homes with palm fronds, which symbolized the victory of life over death.

Romans honored the god Saturn by celebrating Saturnalia in early December. This festival was followed, on the solstice, by Brumalia, from the word bruma meaning “shortest day.”

By 70 A.D., many Roman soldiers had joined a cult around the sun god Mithras, whom they adopted after fighting in Persia, modern day Iran and Syria. Dec. 25 was recognized as Mithras’ birthday.

Because Mithras was so popular with soldiers, his cult spread quickly to all parts of the Roman Empire, Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, the Balkans and gained a strong foothold in Britain. His temples, called Mithraeums, can be found throughout England and Germany.

In the fourth century, the Roman Emperor Constantine proclaimed Dec. 25 the birthday of Jesus Christ, according to many scholars.

“The popularity of Mithraism in the Roman Empire was probably why the early Christian Church decided to celebrate the birth of Jesus at that time,” said Alan Fox, a philosophy professor at the University of Delaware. It was thought that it would be easier to persuade the local people to accept new beliefs if the new religious rituals were superimposed on a holiday from their own religion.

Our Christmas celebrations closely resemble the ancient Roman festivals. People went visiting, gifts were exchanged and feasts were shared. Decorated cookies and cakes were baked and given out to friends. Trees were hung with pieces of metal, and homes were lighted with candles and festooned with holly and other greenery, often in the form of wreaths.

Modern ritual:

As their earliest ancestors did, many Delawareans will celebrate the shortest day of the year, Dec. 21, with reflection and celebration.

Ivo Dominguez Jr. plans to mark the event outside his rural Georgetown home with a bonfire and rituals that symbolize new light and life. Under the night sky, Dominguez, an elder in a religious community known as the Assembly of the Sacred Wheel, will gather with more than 50 fellow Wiccans.

Wicca, a nature religion whose central deity is a mother goddess, is one of the nation’s fastest-growing spiritual traditions, according to the American Academy of Religion. It was formally founded in the United Kingdom in the late 1940s.

To Dominguez and other practitioners, the fascination with the cycles of nature goes back tens of thousands of years. And for people atuned to the Earth and the sun, the winter solstice is an important time.

“It’s a time to gather and renew hope,” Dominguez said.

Many spiritual traditions also have rituals of light at what is also the season of greatest dark.

Judaism has Hanukkah, a festival of lights. And Christians have numerous traditions, including the lighting of a Christmas tree. An annual celebration that remains popular in Delaware’s Swedish community is the St. Lucia Festival.

Because St. Lucia’s name means light, she was known as the saint of light in Norway and Sweden and was considered responsible for turning the tide of long winter days and bringing back the sun.

This year, about 300 people gathered Sunday at the Old Swedes Episcopal Church in Wilmington to watch the pageant. It begins with a procession led by a young girl chosen to represent St. Lucia.

During the pageant, St. Lucia wears a crown of candles, and her attendants wear white gowns with red sashes to symbolize Lucia’s bloody death by sword. She was said to have been beheaded in the year 304 during Christian persecutions in Sicily. St. Lucia’s feast day (the day of her martyrdom) falls on Dec. 13, which, by the Julian calendar, was also the solstice. In 1300, with the change to the Gregorian calendar, the solstice came to fall on Dec. 21.

“The festival of St. Lucia is very important in Sweden because they have a lot of darkness.” said Jo Thompson, a spokeswoman for the Old Swedes church. “The solstice was a signal that spring is coming.”

At Mill Creek Unitarian Universalist Church, an outdoor gathering will help participants connect with nature, said church minister Nancy Dean. The church will celebrate the solstice at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday with a bonfire and service.

“Winter was always a difficult time,” Dean said. “Dread of winter is still a part of our biology.”

The celebration also is a way to honor religions that predate modern ones. Ancient people felt “a need to honor the deities perceived to be in charge of all this,” she said.

Dean will gather fellow celebrants in a circle and join them in chanting and singing. Each participant will hold an evergreen branch, usually holly, and toss it into the fire. The group will share what has been important in their lives during the year. Afterward, a party with a jazz band, cookies and hot chocolate will continue the festivities.

Other area churches also note the winter solstice. The Unitarian Universalist Church of Delaware County in Media, Pa., plans to focus on rebirth. Congregants will gather at 7:30 tonight to welcome the return of the light with song, drumming, dancing and candlelight.

People gain comfort from these celebrations, Dean said.

“It is a hope-filled time because, though it is dark and cold, you know things will get better as the days lengthen,” she said. “Honoring the longest night reminds [people] to see hope during the other dark times of their lives.”

Art from: Megalithic

Brumalia is an ancient Roman winter festival incorporating many smaller festivals celebrating Saturn, Ops and Bacchus. The word Brumalia comes from the Latin bruma meaning “shortest day.” By the Byzantine era, celebrations commenced on 24 November and lasted for a month, until Saturnalia and the “Waxing of the Light.” It is said to have been instituted by Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome.

According to 6th century historian John Malalas1, Romulus entertained his Senators, army and staff throughout the month, assigning each day a letter and inviting those whose names began with the assigned letter to dinner parties. He also encouraged his Senators to likewise entertain their friends and staff in the same manner. According to John the Lydian, sacrifices were made of pigs to Demeter and Cronus and goats were sacrificed to Dionysus2 and speculates that Cronus is honored at this time because of his banishment into the darkness of Tartarus.

The festival marked a break for the Senate and included night-time feasting, drinking, and merriment. During this time, prophetic indications were taken as prospects for the remainder of the winter. It also incorporated a number of smaller holidays associated with various Gods.

Some people celebrated Brumalia by sacrificing goats and pigs, while devotees of the god Dionysus inflated goat skins and then jumped on them. It is also believed that each day of the festival was assigned a different letter of the Greek alphabet, starting with alpha (α) on November 24 and finishing with omega (ω) on December 17.

The festival was celebrated as late as the 6th century, until emperor Justinian’s repression of paganism.

Some modern Pagans use the word Brumalia to simply indicate the winter holiday season including all of its various festivals and activities. This seems quite in keeping with the spirit of the ancient use of the word.

Source: Wikipedia and Witchipedia

A popular snack all over China, glutinous rice balls (tang yuan) are filled with red bean, sesame, peanut, and other sweet fillings that ooze out from mochi-like dumplings skins. The dumpling skins owe their pleasantly gummy texture to glutinous rice flour, which produces a chewier dough.

You’ll find packets of frozen tang yuan at most Chinese supermarkets, and these days the fillings not only come in the standard assortment, but have branched out into fancy-sounding ones like “sweet osmanthanus” and “chestnut and sesame seed.”

The dough for tang yuan is a simple combination of glutinous rice flour, regular rice flour, and water. Once you get the hang of enclosing the dough around nuggets of sweet filling, you’ll find that making your own tang yuan takes no more than half an hour.

The best part about making your own is that you can experiment with all kinds of nuts and pastes. The filling is a simple combination of sugar, lard, and a filling of nuts and/or beans. Instead of ground peanut or sesame, you can use almonds, cashews, and pecans. (To prepare the nuts: roast them, chop them up, and grind them in a mortar and pestle before mixing with lard and sugar.)

Or, if you’ve always found the red bean filling in supermarket tang yuan to be bland, you can make your own from dried adzuki beans. Coconut flakes are a great addition to fillings of any kind.

You can even vary the fat, substituting coconut oil for the traditional lard. I like to use the lard that I confit with for a filling that’s extra meaty and mildly savory. You could also play around with smoky bacon fat.

Really, you can’t go wrong with the filling. Who would turn down chewy rice balls that release a lava-like concoction that’s sweet, nutty, and porky? Even the water in which tang yuan simmers is surprisingly soothing and tasty to sip between rice ball bites. Make the balls in large batches and freeze them for a quick breakfast or dessert.

The sixth day of Christmas (Dec 30) is the day of “Bringing in the Boar.” Two traditions honor the importance of the boar at Solstice tide. In Scandinavia, Frey, the god of sunshine, rode across the sky on his golden-bristled boar. Gulli-burstin, who was seen as a solar image, his spikes representing the rays of the sun.

In the ancient Norse tradition, the intention was to gain favor from Frey in the new year. The boar’s head with an apple in his mouth was carried into the banquet hall on a gold or silver dish to the sounds of trumpets and the songs of minstrels.

In Scandinavia and England Saint Stephen (whose feast day is Dec 26) is shown as tending to horses and bringing a boar’s head to a Yuletide banquet. Christmas ham is an old tradition in Sweden and may have originated as a winter solstice boar sacrifice to Freyr.

Here’s a song from 1607:

The Boar is dead,

Lo, here is his head,

What man could have done more

Than his head off to strike,

Meleager like.

And bring it as I do before.

His living spoiled,

Where good men toiled,

Which makes kind Ceres sorry;

But now, dead and drawn,

he is very good brawn,

And we have brought it for ye.

Then set down the swineherd,

The foe of the vineyard,

Let Baccus crown his fall;

Let this boar’s head and mustard,

Stand for pig,goose and custard,

And so ye are welcome all.

From: The Winter Solstice and other sources.

The wren, the wren, The king of all birds,

On St. Stephen’s Day Is caught in the furze.

One of the most remarkable and dramatic Solstice customs involving animals is the Hunting of the Wren, which traditionally takes place on Boxing Day or St. Stephen’s Day. The custom lasted longest in Wales and the Isle of Man and still takes place today in Ireland. A description from 1840 describes it thus:

For some weeks preceding Christmas, crowds of village boys may be seen peering into hedges, in search of the tiny wren; and when one is discovered the whole assemble and give wager chase until they have slain the little bird. In the hunt the utmost excitement prevail; shouting, screeching, and rushing, all sorts of missiles are flung at the puny mark… From bush to bush, from hedge to hedge, is the wren pursued until bagged with as much pride and pleasure as the cock of the woods by the more ambitious sportsman… On the anniversary of St. Stephen the enigma is explained. Attached to a huge holly bush, elevated on a pole, the bodies of several little wrens are borne about… through the streets in procession… And every now and then stopping before some popular house and there singing the Wren song.

Various versions of this song have survived. Here is a typical one:

The wren, the wren, the king of all birds,

On St. Stephen’s Day was caught in the furze;

Though his body is small, his family is great,

So if it please your honor, give us a treat.

On Christmas day I turned a spit;

I burned my finger, I feel it yet.

Up with the kettle, down with the pan.

Give us some money to bury the wren.

The antiquity of this rather barbaric custom is clear enough. At one time the Wren, the “king of all birds,” must have represented the dying year king and was sacrificed on his behalf for the good of the land. The following story from Scotland suggest the reason for this rather plain little bird being addressed as King.

The Parliament of Birds:

At a gathering of birds, it was decided to elect a king by seeing which could fly the highest, and nearest to the sun. The eagle’s broad strong wings bore it higher than any other. It was about to acclaim its prowess, when it became aware of a “whirr-chuck” sound – the little wren had flown yet higher than the eagle, because it was cheekily perched on it’s back.

For many years during the 18th and 19th centuries, the Irish Wren Boys were accompanied by masked guisers, including the ubiquitous lair bhan or White Mare. Nowadays, due in part to a shortage of wrens and to a somewhat more bird-conscious awareness, they are seldom hunted. Although the Wren Boys still circulate in Ireland, they no longer kill a wren, but proceed from house to house with a decorated cage.

Here is a different wren song sung by the guisers in Pembrokeshire, England, where the custom is no longer practiced, but the sacredness of the bird is remembered:

Joy, health, love and peace be all here in this place.

By your leave we will sing concerning our king.

Our king is well dressed, in silks of the best,

In ribbons so rare, no king can compare.

We have traveled many miles, over hedges and stiles,

In search of our king, until you we bring.

Old Christmas is past, Twelfth Night is the last,

And we bid you adieu, great joy to the new.

It is not of the newborn king of Winter, the Wondrous Child they are speaking, but King Wren, who is remembered in a curious song from Oxfordshire, that manages to encapsulate the more ancient significance of the custom.

From: The Winter Solstice

Art by: Cathy Johnson