Native American

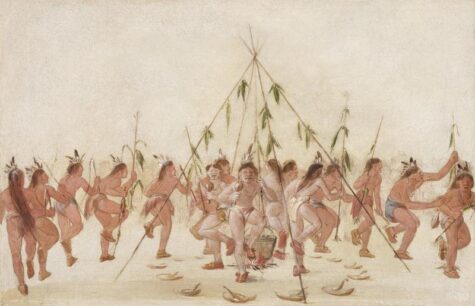

The Green Corn Ceremony typically occurs in late July– early August, determined locally by the ripening of the corn crops. The ceremony is marked with dancing, feasting, fasting and religious observations.

The Green Corn Ceremony is a celebration of many types, representing new beginnings. Also referred to as the Great Peace Ceremony, it is a celebration of thanksgiving to Hsaketumese (The Breath Maker) for the first fruits of the harvest, and a New Year festival as well.

The Feast of Green Corn and Dance gives honor to Mantoo (Creator) provider of all things and celebrates our harvest, ancestors, elders, veterans, family and Native American heritage.

The Green Corn Ceremony is an annual ceremony practiced among various Native American peoples associated with the beginning of the yearly corn harvest.

These ceremonies have been documented ethnographically throughout the North American Eastern Woodlands and Southeastern tribes. Historically, it involved a first fruits rite in which the community would sacrifice the first of the green corn to ensure the rest of the crop would be successful.

These Green Corn festivals were practiced widely throughout southern North America by many tribes evidenced in the Mississippian people and throughout the Mississippian Ideological Interaction Sphere. Green Corn festivals are still held today by many different Southeastern Woodland tribes.

Literally the spirit of the corn in Native American traditions, Corn Mother brings with her the bounty of earth, its healing capabilities, it’s nurturing nature, and its providence.

- Symbols: Corn; Corn Sheaves

- Themes: Abundance; Children; Energy; Fertility; Harvest; Health; Grounding; Providence; Strength

This is the season when Corn Mother really shines, beautiful with the harvest. She is happy to share of this bounty and give all those who seek her an appreciation of self, a healthy dose of practicality, and a measure of good common sense.

To Do Today:

Around this time of year the Seminole Indians (in the Florida area) dance the green corn dance to welcome the crop and ensure ongoing fertility in the fields and tribe. This also marks the beginning of the Seminole year. So, if you enjoy dancing, grab a partner and dance? Or, perhaps do some dance aerobics. As you do, breathe deeply and release your stress into Corn Mother’s keeping. she will turn it into something positive, just as the land takes waste and makes it into beauty.

Using corn in rituals and spells is perfectly fitting for this occasion. Scatter cornmeal around the sacred space to mark your magic circle, or scatter it to the wind so Corn Mother can bring fertility back to you. Keeping a dried ear of corn in the house invokes Corn Mother’s protection and luck, consuming corn internalizes her blessings.

The traditional Ceremony:

The Busk or Green Corn Ceremony is the celebration of the New Year, so at this time all offenses are forgiven except for rape and murder, which are executable or banishable offenses.

In modern tribal towns and Stomp Dance societies only the ceremonial fire, the cook fires and certain other ceremonial objects will be replaced. Everyone usually begins gathering by the weekend prior to the ceremony, working, praying, dancing and fasting off and on until the big day.

The whole festival tends to last seven-eight days, if you include the historical preparation involved (without the preparation, it lasts about four days).

- Day One

The first day of the ceremony, people set up their campsites on one of the square ceremonial grounds. Following this, there is a feast of the remains of last year’s crop, after which all the men of the community begin fasting (historically, the women were considered too weak to participate). That night there is a social stomp dance, unique to the Muscogee and Southeastern cultures.

- Day Two

Before dawn on the second day, four brush-covered arbors are set up on the edges of the ceremonial grounds, one in each of the sacred directions.

For the first dance of the day, the women of the community participate in a Ribbon or Ladies Dance, which involves fastening rattles and shells to their legs perform a purifying dance with special ribbon-clad sticks to prepare the ceremonial ground for the renewal ceremony.

The ceremonial fire is set in the middle of four logs laid crosswise, so as to point to the four directions. The Mico (head priest) takes out a little of each of the new crops (not just corn, but beans, squash, wild plants, and others) rubbed with bear oil, and it is offered together with some meat as “first-fruits” and an atonement for all sins.

The fire (which has been re-lit and nurtured with a special medicine by the Mico) will be kept alive until the following year’s Green Corn Ceremony. In traditional times, the women would sweep out their cook-fires and the rest of their homes and collect the filth from this, as well as any old clothing and furniture to be burnt and replaced with new items for the new year.

The women then bring the coals of the fire into their homes, to rekindle their home fires. They can then bake the new fruits of the year over this fire (also to be eaten with bear oil). Many Creeks also practice the sapi or ceremonial scratches, a type of bloodletting in the mid morning, and in many tribes the men and women might rub corn milk, ash, white clay, or analogous mixtures over themselves and bathe as a form of purification.

They also drink a medicine referred to as the “White Drink.” (English traders referred to it as the “Black Drink” due to its dark liquid which froths white when shaken before drinking).

This White Drink, known to strangers as Carolina Tea, is a caffeine-laden mixture of seven to fourteen different herbs, the main ingredient being assi-luputski, Creek for “small leaves” of Yaupon Holly.

This medicine was intended to help receive purification, as it is a purgative when consumed in mass amounts. (Historically, only men drank enough of the liquid to throw up.) The purgative was consumed to clean the dietary tract of last year’s crop and to truly renew oneself for the new year.

- Day Three

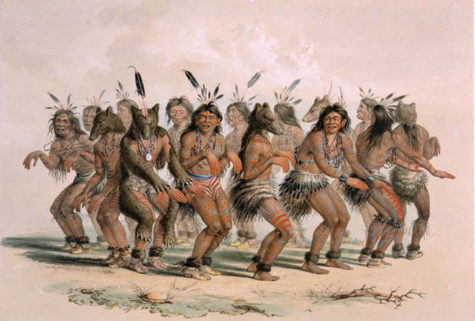

While the second day tends to focus on the women’s dance, the third is focused on the men’s. After the purification of the second day, men of the community perform the Feather Dance to heal the community.

The fasting usually ends by supper-time after the word is given by the women that the food is prepared, at which time the men march in single-file formation down to a body of water, typically a flowing creek or river for a ceremonial dip in the water and private men’s meeting. They then return to the ceremonial square and perform a single Stomp Dance before retiring to their home camps for a feast.

During this time, the participants in the medicine rites are not allowed to sleep, as part of their fast. At midnight a Stomp Dance ceremony is held, which includes feasting and continues on through the night. This ceremony usually ends shortly after dawn.

- Day Four

The fourth day has friendship dances at dawn, games, and people later pack up and return home with their feelings of purification and forgiveness. Fasting from alcohol, sexual activity, and open water will continue for another four days.

More Information

Puskita, commonly referred to as the “Green Corn Ceremony” or “Busk,” is the central and most festive holiday of the traditional Muscogee people. It represents not only the renewal of the annual cycle, but of the spirit and traditions of the Muscogee. This is representative of the return of summer, the ripening of the new corn, and the common Native American traditions of environmental and agricultural renewal.

Historically in the Seminole tribe, 12-year-old boys are declared men at the Green Corn Ceremony, and given new names by the chief as a mark of their maturity.

Several tribes still participate in these ceremonies each year, but tribes who have historic tradition within the ceremony include the Iroquois, Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, and Seminole tribes. Each of these tribes may have their own variations of celebration, dances and traditions, but each performs a new-year’s ceremony involving fasting and several other comparisons each year.

Sources:

The Powamu Festival is the mid-winter ceremony and also called the Bean Planting Festival. It is observed in late January or early February. The celebration lasts 8 days and is mainly celebrated by the Hopi Indians in Arizona.

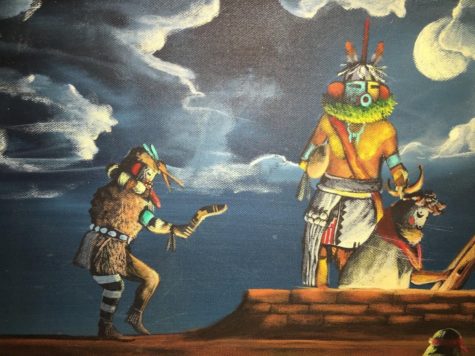

The Hopis call their ancestral spirits, Katchinas. They believe that for 6 months of the year, these spirits leave their mountain homes and visit the tribe. When they do this, they bring along with them good health to the Hopi and rain for their crops. The Powamu Festival celebrates the spirits return, just like the Niman Katchina ceremony in July celebrates their departure.

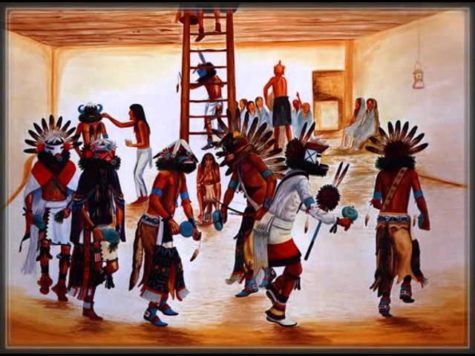

The preparations for the ceremony include repainting of the masks that will be worn by those Hopi who impersonate the Katchinas. On the third day, young men bring baskets of wet sand that they leave near the entrance to the kiva, the ceremonial meeting room (see more about this on Wuwuchim page). A hot fire also burns in every kiva of very Hopi village the entire 8 days of the Powamu Festival. Blankets are also stretched across the opening so that the atmosphere inside is similar to a hothouse.

Each man who enters the kiva during this period carries a basket (or bowl) of sand into it. He also plants a handful of beans, which sprout really fast due to all the heat and humidity inside the kiva.

Why bean sprouts? The Hopi believe that bean sprouts represent fertility. Because the Hopi rely strongly on the Katchinas to bring rain (and other good weather conditions) essential to the growth of their crops, bean sprouts also symbolize the approaching spring too.

The Powamu comes to it’s conclusion with a dance that takes place in the nine kivas that dot the northeastern Arizona mesa. The bodies of the dancers are painted red and white and they wear squash blossoms in their hair. These are really yucca fibers twisted into the shape of a squash blossom. They also wear white kilts and sashes, plus leggings with a fringe of shells tied down the side.

The dance takes place inside the hot kiva and is done in two lines. When the dance is over, the dancers then leave for the next village’s kiva, and another group arrives. So, by the time the night is over, each group will have danced at all of the nine kivas.

Then, the Katchinas arrive the next morning wear masks and painted bodies. They bring dolls and rattles for the girls; and, bow and arrows for the boys. Both of the boys and girls get the green bean sprouts that have been growing in the hot kivas.

Clowns run around making jokes, tripping each other and performing pantomines for everyone’s pleasure and fun. The conclusion of the Powamu ends with a feast in which bean sprouts are the main ingredient.

From this time until their departure in July, the Katchinas appear regularly in masked ceremonies performed in the Hopi villages.

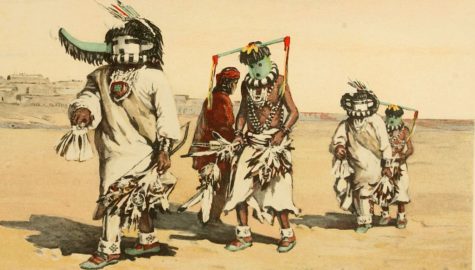

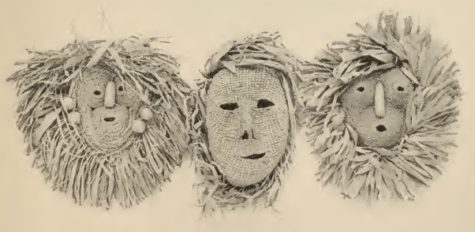

The men who impersonate the Katchinas wear masks which vary from year to year. A few of the masks will, however, remain the same. Before the dance, the masks are repainted and refurbished. They are made to fit closely over the head, hiding it totally. There is also a ruff of feathers, fur or spruce at the neck. The face on the mask usually resembles a bird, a beast, a monster or a man or a combination of all of these.

Those who wear the Katchina masks usually also carry an object associated with the being they are suppose to represent (i.e. bow and arrow, a yucca whip or feathers.)

The female Katchinas (who are not really women but are impersonated by the men) wear wigs or long hair styled in flat swirls over the ears known as squash blossoms. This hair style represents virginity.

The Soyokmana is a witch-like creature that carries a crook and a bloody knife. She goes along with the Katchinas as they go from Hopi village to another visiting their kivas. This group also goes from house to house demanding food, receiving gifts and presenting bean sprouts.

When the food they are offered does not meet their requirements, the Katchinas get upset and make hooting and whistling noises and refuse to leave until they have been properly fed! (This sort of reminds me of trick or treating on Halloween.) Sometimes that mean ol’ Soyokamana will use her crook to hook a child around the neck and hold him or her there, screaming in terror. Parents tell their children that this is a punishment for being naughty.

The Flogging Ceremony

Up until a Hopi child is 9 or 10, they believe that the Katchinas are superhuman. So when Hopi children, who have been seeing the Katchinas at many ceremonial dances grow up, they are told that the real Katchinas no longer visit the earth, but are merely impersonated by men wearing masks.

The price for this sudden wisdom is to participate in a ritual flogging or whipping ceremony. Now, the children are NEVER struck hard enough to cause serious injury or pain! This ritual is not intended to be cruel. In fact, sometimes a child who is really frightened, isn’t flogged at all but has a yucca whip whirled over his or her head. Occasionally, an adult will be flogged too, which is believed to promote healing.

For four successive mornings, the child who has been flogged is taken to a special place on the mesa where he or she can make an offering at a shrine and casts meal towards the sun. During the first 3 days of this 4 day period, the child is not allowed to eat salt or meat. But, on the fourth day, these rules are lifted. And, from this time on, the child is now allowed to look at the Katchinas without their masks and at other sacred objects in the kiva without incurring any punishment.

Source: Brownielocks

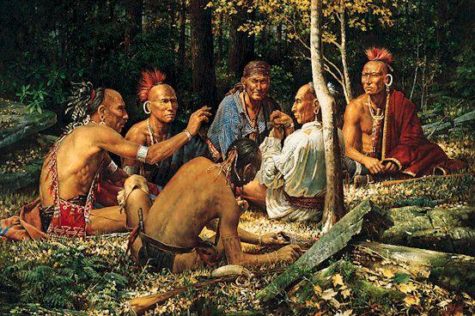

The Iroquois Mid-Winter Ceremony, for continuation of all life-sustaining things is a series of rituals, observed by the six tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy, which celebrates new beginnings and serves as a spiritual new year. The ceremony does not have an official date on the calendar, but rather is determined when the first new moon arrives while both the Ursa Major and Ursa Minor constellations are visible, which occurs in either February or January.

- According to one calendar, this will be Feb 19 thru Feb 28, in 2018.

- According to other star maps, Ursa Major and Ursa Minor can be seen above the horizon in northern areas all year.

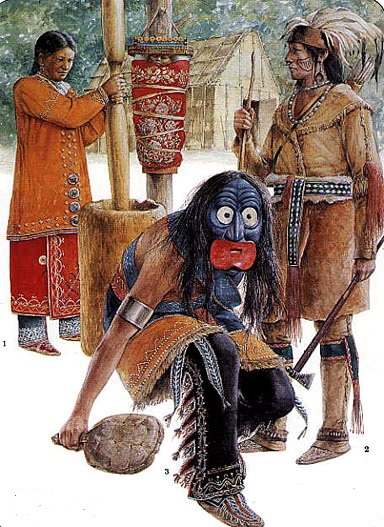

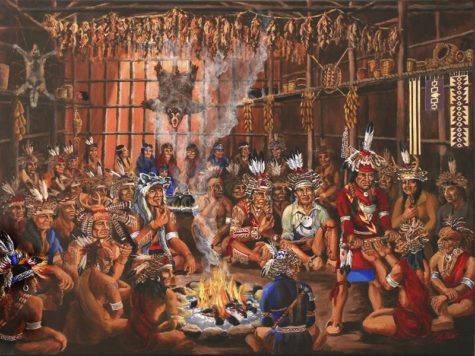

The major events of the Midwinter Ceremony consist of the Tobacco Invocation, the Dream Sharing Ritual, the False Face Society, the Peach Stone Game, the Bear Dance, the White Dog Sacrifice, the Great Feather Dance, The Big Heads and the Stirring of the Ashes, and a closing ceremony. These events take place over the course of ten days with no specific order, but generally begin with The Big Heads and the Stirring of the Ashes and ends with a closing ceremony.

- Big Heads and the Stirring of the Ashes

Generally, the first of the activities is the Big Heads and the Stirring of the Ashes. A group of anonymous messengers called the Big Heads visit the tribe’s longhouse. They wear ceremonial outfits made of buffalo skins and braided corn husk masks which symbolize the hunt and the harvest.

They also carry a corn mashing mallet used in the Stirring of the Ashes. In the Stirring of the Ashes, the Big Heads go from house to house stirring the ashes in fire pits of each household while they ask that the New Year brings renewal and fertility to the land. This is gesture of gratitude to “The Creator” as ashes serve as a symbol of the earth and the cycle of life.

- Tobacco Invocation

The next ritual to usually take place after the Stirring of the Ashes is the Tobacco Invocation. It consists of sprinkling tobacco in the embers remaining from the Stirring of the Ashes or outright smoking as an offering. The smoke that rises from the burning tobacco symbolically rises to the heavens to sign of giving thanks and to give messages to the Creator and other spirits.

- Dream Sharing Ritual

The Dream Sharing Ritual serves as a ritual of healing. It serves as a way to get rid of troubling thoughts and a way to make wishes come true as the Iroquois believe that dreams represent ways to resolve real life problems. Tribe members would describe their dreams in front of others so they may give their interpretation of the events that take place in the dreams.

The person who has the best interpretation has to then aid the tribe member in seeing that the issue gets resolved. For dreams that represent physical or mental ailments, they dreamer is sent to the False Face Society which is a group of medicine men.

- False Face Society

The False Face Society is a group of Iroquois medicine men who wear masks made out of wood. These people can consist of either men or women, but only the men wear the traditional masks. They are said to have the ability to scare off the evil spirits that cause illness. Those who are deemed of needing healing during the Dream Sharing Ritual are sent to these medicine men during their gathering. Healing rituals consist generally of blowing or rubbing hot ashes from a fire on those in need of curing.

- Bear Dance

The Bear Dance is another healing ritual that coincides with the False Face Society gathering. It is conducted by both men and women by lumbering and waddling like bear counter clockwise around a person that was ill.

This can be done either privately or publicly. The Iroquois believed that this dance can heal the problems of person that were placed upon them from the previous year.

- Peach Stone Game

The next event is the Peach Stone Game. This game symbolizes the Iroquois creation story where the Creator and his evil brother played a game in competition during the creation of the Earth, the renewal of the Earth like the Stirring of the Ashes, and the battle for survival of crops.

The game consists of six peach pits which are colored black (through burning for example) on one side. They are placed in a bowl and shaken while two teams take turns placing bets in the form of beans on how many black sides will face up. The teams are given an equal number of beans, and the first team to lose all of their beans loses the match. The results of this game are also used to predict the success of the coming year’s harvest.

- White Dog Sacrifice

One of the following events is the White Dog Sacrifice. Originally, this ritual consisted of killing a white dog, a symbol of purity, by strangulation as to leave no marks. The dog was then adorned in red paint, feathers, beads, wampum, and ribbons. It was placed on fire along with tobacco so that smoke may carry their, sacrifice, and prayers to the Creator.

Today, however, the act of killing a white dog is replaced by a white basket due to the animal cruelty in the original proceedings of the ritual.

- Great Feather Dance

The final event before the closing ceremonies is the Great Feather Dance. The dance is held on eight night of the nine-day festival, and serves as way to welcome the new spiritual year as well as thanking the Creator. Dancers wear traditional tribal clothing and turtle shell rattles, and dance to two singers that sit facing each other. They give thanks to all the Creator has bestowed upon them during the previous year by dancing in rhythm and shaking the rattles.

The event finally concludes with a closing ceremony where a speaker presenting an overview of the events and address of thanksgiving. New tribal council members who will lead the people until the next event are chosen and presented to the crowd. By the end of this ceremony, all members of the tribe are purified and a new year is welcomed.

Source: First Nation Rituals

- Themes: Freedom; Perspective; Overcoming; Health; Power; Destiny; Air Element; Movement

- Symbols: Feathers (not Eagle – gathering these is illegal)

- Presiding Goddess: Mother of All Eagles

About the Mother of All Eagles:

On the warm summer winds, Eagle Mother glides into our reality, carries us above our circumstances, and stretches our vision. Among Native Americans, the Eagle Mother represents healing, her feathers often being used by shamans for this purpose. Beyond this, she symbolizes comprehension, finally coming to a place of joyfully accepting our personal power over destiny.

To Do Today:

On this day (June 20), in 1982, President Reagan declared Bald Eagle Day to honor the American emblem of freedom. In Native American tradition, this emblem and the Eagle Mother reconnect us with sacred powers, teaching us how to balance our temporal and spiritual life on the same platter.

Find a new, large feather for an Eagle Mother talisman. Wrap the pointed end with cloth crisscrossed by leather thongs or a natural fabric ribbon. Each time you cross the leather strings, say:

______ bound within;

when released by wind, let the magick begin.

Fill in the blank with the Eagle Mother attributes you desire, then have the feather present or use it in rituals or spells to disperse incense, thereby releasing its magic on the winds.

From 365 Goddess