Ireland

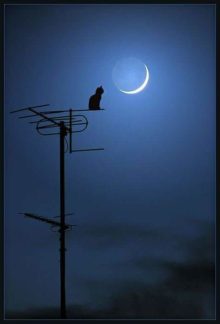

On August 17, Cat Nights Begin, harking back to a rather obscure Irish legend concerning witches; this bit of folklore also led to the idea that a cat has nine lives.

The term Cat Nights refers to a rather obscure old Irish legend concerning witches and the belief that a witch could turn herself into a cat eight times, but on the ninth time (August 17), she couldn’t regain her human form, thus remaining a cat forever.

This bit of folklore also gives us the saying, “A cat has nine lives.”

Because August is a yowly time for cats, this may have prompted the speculation about witches on the prowl in the first place.

Here’s a poem in honor of Cat Nights:

Cat Nights

By old Irish lore

on the 17th of August

more cats are among us

than ever before.

It is said that witches

can turn into a cat.

But no more than eight switches

as a matter of fact.

On the ninth switch

they cannot regain

their life as a witch.

A cat they must remain.

So if in mid August

you should hear the cats yowl

amongst sounds of the locust

when cats are on the prowl

Then you will know

as lore was told over time

that cats will show

lives as many as nine.

By V. Neumann

Found at: The Old Farmer’s Almanac

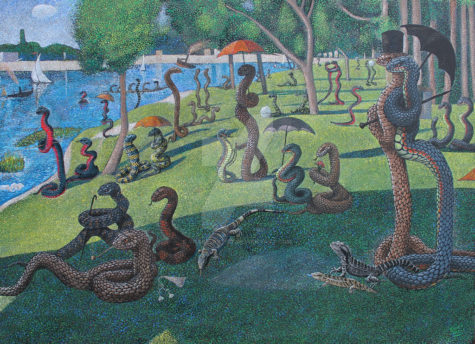

Snake Sunday is a holiday celebrated the Sunday before St. Patrick’s Day. Typically it is used as a way of dealing with a hangover from celebrating a “pseudo” St. Patrick’s Day which is commonly done by partaking of the great Irish tradition on a Saturday night when the actual holiday is during the work week.

Commonly in honor of Snake Sunday, celebrators will exclaim “SNAKE SUNDAY” typically in unison. This cheer usually follows either the question, “What day is it?” some variant thereof, or if someone says “Happy Snake Sunday!”

Example:

Ted: “Hey Lance, how you doing today?”

Lance: “Hey Ted, pretty hungover from celebrating St. Patrick’s Day last night, but otherwise it’s a great Snake Sunday!”

Ted/Lance: “SNAKE SUNDAY!!!”

Source: Urban Dictionary

Gobnait is Irish for Abigail which means “Brings Joy”. As the patron saint of beekeepers, her name also has been anglicized as Deborah, meaning “Honey Bee.” This Irish saint is a version of the deity Domna, patroness of sacred stones and cairns. The center of her worship was at Ballybourney, Co. Cork, Ireland.

Her feast day, February 11 is called “Pattern Day” in the parishes of Dún Chaoin and in Baile Bhúirne, and is regarded as both holiday and holy day. In one tradition, a medieval wooden carving of Gobnait, about two feet high, kept in a church drawer during the year, is brought out. Parishioners bring a ribbon to ”measure” the statue. This ribbon is then taken home to use when special blessings are needed.

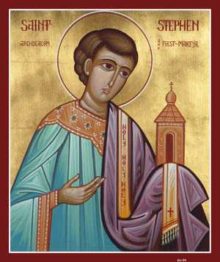

St Stephen’s Day, celebrated every year on 26 December, draws together a number of solstice traditions. We have already learned of the ancient practice of hunting the wren, the King of all birds (Day of the Wren), and of displaying the tiny corpse around the villages throughout Britain and Ireland. The origins of this custom probably date back to the time when kings were slaughtered after a year in office – and in France up until the seventeenth century the first person to kill and display the body of the wren was chosen king for a day at the time of the Feast of Fools.

St Stephen’s Day, celebrated every year on 26 December, draws together a number of solstice traditions. We have already learned of the ancient practice of hunting the wren, the King of all birds (Day of the Wren), and of displaying the tiny corpse around the villages throughout Britain and Ireland. The origins of this custom probably date back to the time when kings were slaughtered after a year in office – and in France up until the seventeenth century the first person to kill and display the body of the wren was chosen king for a day at the time of the Feast of Fools.

St. Stephen himself, according to legend, was once a servant of the biblical King Herod. When he saw the star of the nativity he sought to know more of the Child of Wonder born in the stable, and as a result changed his allegiance to a new king.

The association of the wren killing with St. Stephen’s Day may well derive from a legend of the saint’s visit to Scandinavia. In this story Stephen, having been captured by soldiers, was about to make his escape when the wren uttered its noisy song and awoke his guards – for which reason the wren is said to be unlucky and it is, indeed, considered a misguided act to kill the bird on any other day of the year.

St. Stephen’s Day in Wales is known as Gŵyl San Steffan. One ancient Welsh custom, discontinued in the 19th century, included bleeding of livestock and “holming” by beating with holly branches of late risers and female servants. The ceremony reputedly brought good luck.

St. Stephen’s Day (Sant Esteve) is a traditional Catalan holiday. It is celebrated with a big meal including canelons. These are stuffed with the ground remaining meat from the escudella i carn d’olla, turkey, or capó of the previous day.

Stephanitag is a public holiday in mainly Catholic Austria. In the Archdiocese of Vienna, the day of patron saint St. Stephen is even celebrated on a Sunday within the Octave of Christmas, the feast of the Holy Family. Similar to the adjacent regions of Bavaria, numerous ancient customs still continued to this day, such as ceremonial horseback rides and blessing of horses, or the “stoning” drinking ritual celebrated by young men after attending church service.

Another old tradition was parades with singers and people dressed in Christmas suits. At some areas these parades were related to checking forthcoming brides. Stephen’s Day used to be a popular day for weddings as well. These days a related tradition is dances of Stephen’s Day which are held in several restaurants and dance halls.

In Finland the most well known tradition linked to the day is “the ride of Stephen’s Day” which refers to a sleigh ride with horses. These merry rides along village streets were seen in contrast to the silent and pious mood of the preceding Christmas days. This tradition more than likely relates to the following legend about this saint, who is generally called the first Christian martyr.

The story is as follows:

St Stephen is said to have reached Sweden, and to have established a church there from which he rode forth to preach and teach the Christian message. To enable him to travel the great distances through often inhospitable country he had a string of five horses two red, two white, and one dappled. Whenever one of these became tired Stephen would simply mount another. However, as he was traveling through a particularly deep stretch of forest, he was set upon by brigands, who killed him and tied his body to the back of an unbroken colt. This beast, bearing the saint’s body, galloped all the way back to Stephen’s home. His grave there subsequently became a place of pilgrimage and perhaps because of the association with horses, sick beasts were brought there for healing. Stephen is still known as the patron saint of horses to this day.

The themes of St. Stephen’s day, then, have to do with death and resurrection and animals. The former makes it particularly appropriate that it is on this day that the Mummer plays are most often performed.

From: The Winter Solstice

The wren, the wren, The king of all birds,

On St. Stephen’s Day Is caught in the furze.

One of the most remarkable and dramatic Solstice customs involving animals is the Hunting of the Wren, which traditionally takes place on Boxing Day or St. Stephen’s Day. The custom lasted longest in Wales and the Isle of Man and still takes place today in Ireland. A description from 1840 describes it thus:

For some weeks preceding Christmas, crowds of village boys may be seen peering into hedges, in search of the tiny wren; and when one is discovered the whole assemble and give wager chase until they have slain the little bird. In the hunt the utmost excitement prevail; shouting, screeching, and rushing, all sorts of missiles are flung at the puny mark… From bush to bush, from hedge to hedge, is the wren pursued until bagged with as much pride and pleasure as the cock of the woods by the more ambitious sportsman… On the anniversary of St. Stephen the enigma is explained. Attached to a huge holly bush, elevated on a pole, the bodies of several little wrens are borne about… through the streets in procession… And every now and then stopping before some popular house and there singing the Wren song.

Various versions of this song have survived. Here is a typical one:

The wren, the wren, the king of all birds,

On St. Stephen’s Day was caught in the furze;

Though his body is small, his family is great,

So if it please your honor, give us a treat.

On Christmas day I turned a spit;

I burned my finger, I feel it yet.

Up with the kettle, down with the pan.

Give us some money to bury the wren.

The antiquity of this rather barbaric custom is clear enough. At one time the Wren, the “king of all birds,” must have represented the dying year king and was sacrificed on his behalf for the good of the land. The following story from Scotland suggest the reason for this rather plain little bird being addressed as King.

The Parliament of Birds:

At a gathering of birds, it was decided to elect a king by seeing which could fly the highest, and nearest to the sun. The eagle’s broad strong wings bore it higher than any other. It was about to acclaim its prowess, when it became aware of a “whirr-chuck” sound – the little wren had flown yet higher than the eagle, because it was cheekily perched on it’s back.

For many years during the 18th and 19th centuries, the Irish Wren Boys were accompanied by masked guisers, including the ubiquitous lair bhan or White Mare. Nowadays, due in part to a shortage of wrens and to a somewhat more bird-conscious awareness, they are seldom hunted. Although the Wren Boys still circulate in Ireland, they no longer kill a wren, but proceed from house to house with a decorated cage.

Here is a different wren song sung by the guisers in Pembrokeshire, England, where the custom is no longer practiced, but the sacredness of the bird is remembered:

Joy, health, love and peace be all here in this place.

By your leave we will sing concerning our king.

Our king is well dressed, in silks of the best,

In ribbons so rare, no king can compare.

We have traveled many miles, over hedges and stiles,

In search of our king, until you we bring.

Old Christmas is past, Twelfth Night is the last,

And we bid you adieu, great joy to the new.

It is not of the newborn king of Winter, the Wondrous Child they are speaking, but King Wren, who is remembered in a curious song from Oxfordshire, that manages to encapsulate the more ancient significance of the custom.

From: The Winter Solstice

Art by: Cathy Johnson